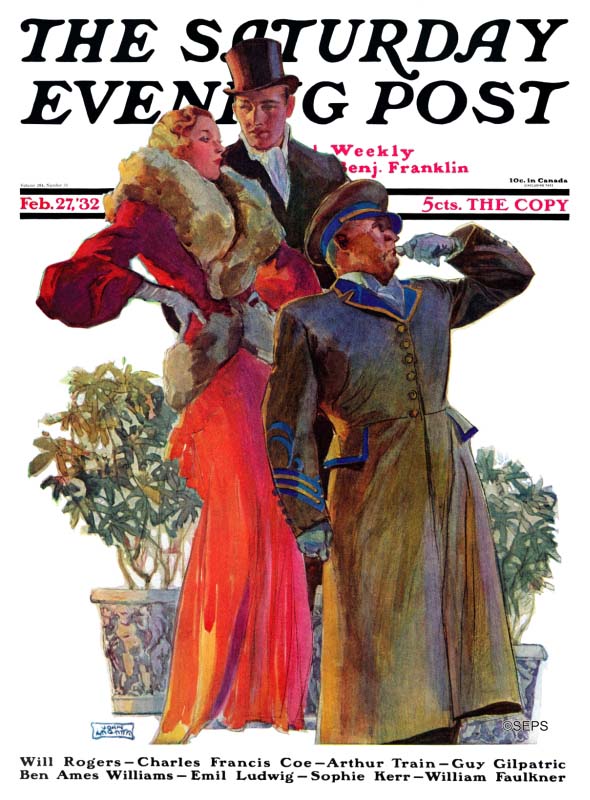

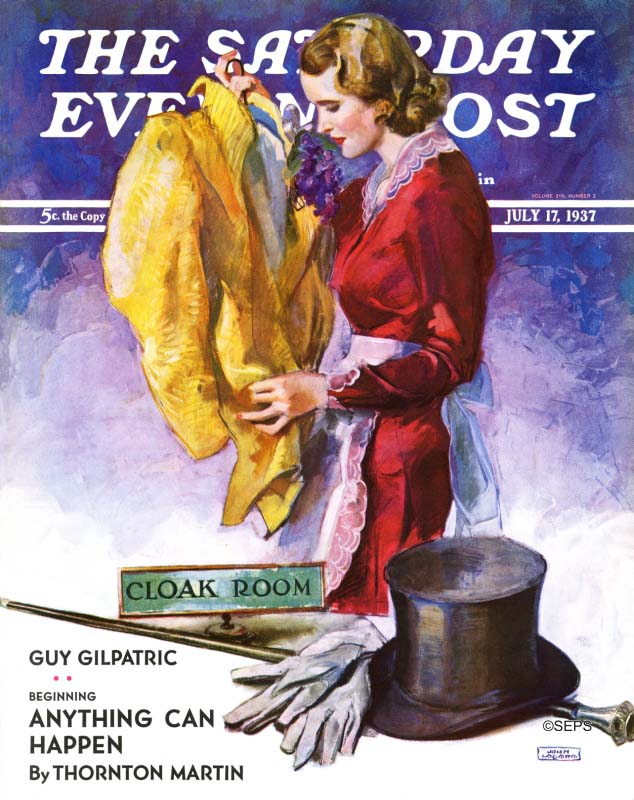

The Art of the Post: John La Gatta — The Painter of Glamorous Women

The young artist John La Gatta had little to offer a future bride.

A poor, humble immigrant, he arrived in America after a sickly childhood in Naples, Italy. He grew up in a rough neighborhood in New York. He aspired to be an artist, but jobs were scarce and progress was slow.

In 1916 La Gatta met and fell in love with the beautiful Florence Eugenia Olds. Despite his lack of prospects, he persuaded her to marry him, and the couple were wed on January 1, 1918.

La Gatta and his wife started out so poor they couldn’t even afford dishes. They would eat off the artist’s palette after he washed off the paints at the end of his working day. They had no shower, but La Gatta improvised one by hanging a sprinkling can from a string, with a contraption to tip the can and release the water. He had no drawing board but was able to turn a chair upside-down to serve as his drawing table. Gradually he began getting assignments for sketches and small spot illustrations, especially for advertisements.

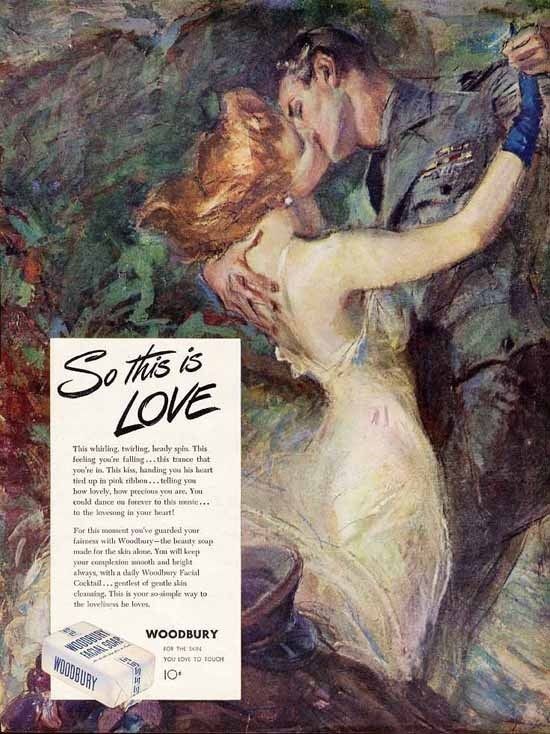

La Gatta couldn’t afford regular models like a professional artist, but he painted several pictures of his wife and put them in a portfolio to show prospective employers his capabilities. That inspired portfolio changed his professional life. La Gatta painted in a romantic style that began to attract clients.

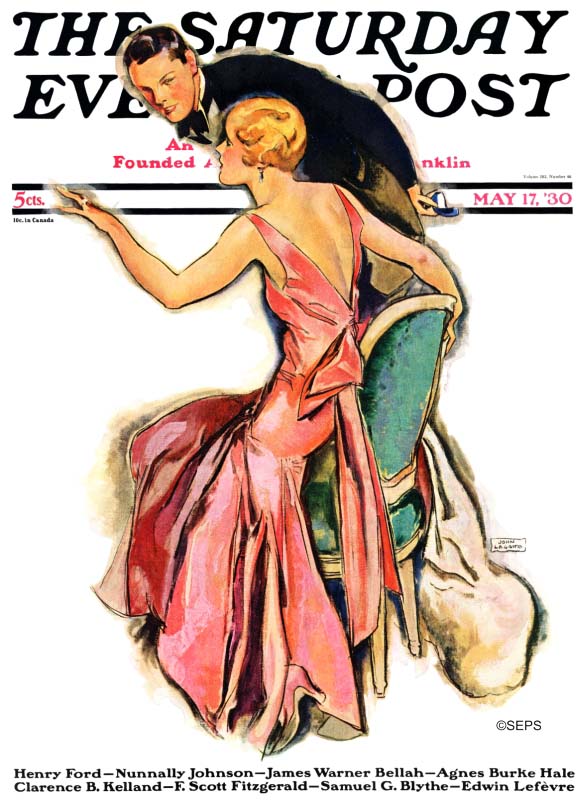

La Gatta thought his big break had arrived in 1923 when he was approached by Arthur McKeogh, the art director for The Saturday Evening Post. McKeogh had seen La Gatta’s pictures in advertisements in the backs of magazines and believed he had the talent to illustrate stories for the Post — a better paying, higher class type of work. However, after La Gatta’s first illustration for the Post, the magazine did not call him back. It turned out that George Horace Lorimer, the big boss at the Post, did not like La Gatta’s work. The women he painted were romantic and glamorous, nothing like the women Lorimer thought would appeal to the Post’s middle American readers.

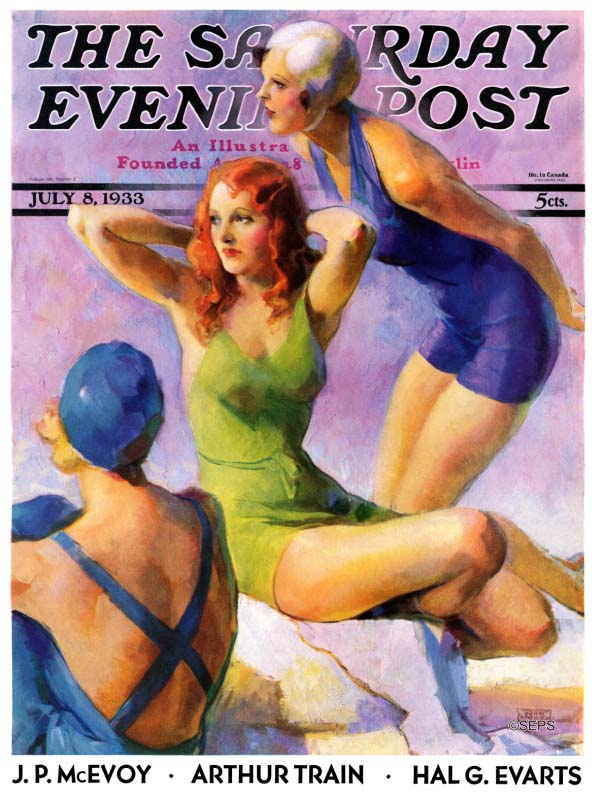

But the tastes of Post readers were about to change dramatically. The 1920s started as a decade of prosperity and frivolity, but they ended with the Great Depression, with readers looking for escape and fantasy. As illustration historian Walt Reed wrote, La Gatta’s style was about to become the rage:

A sea change had occurred between the ‘20s and ‘30s. The smart, brittle sophistication in the drawings of that prosperous decade were no longer appropriate during the years of the sobering Great Depression. Even [drawings of] flappers were out of sync with the times.… frivolity was replaced by unemployment and discouragement. As hard times deepened, the public looked for an escape — which would be provided by Hollywood, radio and magazine addiction. The new watchword was “glamour” and La Gatta was to become its leading exponent.”

Lorimer, the editor of the Post, was persuaded by his own sons that his taste was out of touch and that La Gatta’s style was what current readers wanted to see. La Gatta was rehired and developed a close relationship not only with the Post’s art director but with Lorimer himself.

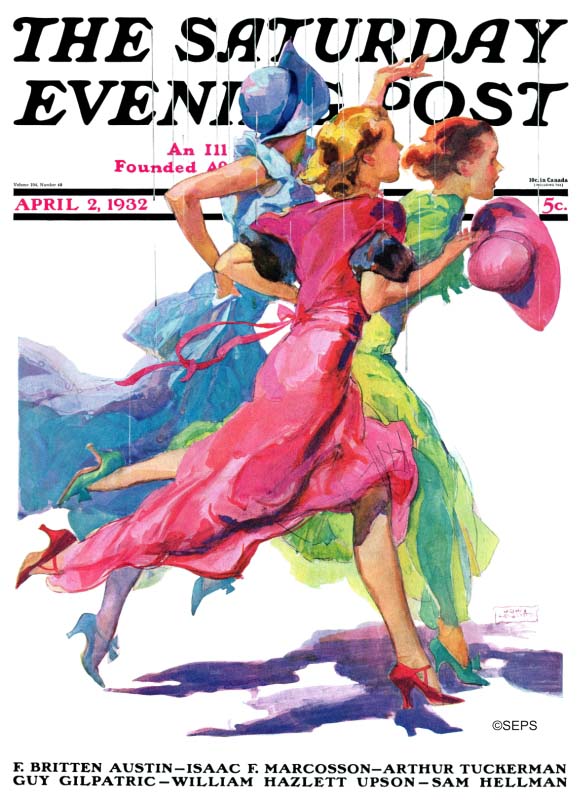

La Gatta’s pictures became hugely popular with the public. His work was constantly in demand by the Post and several other top magazines. He became fabulously wealthy. In an era where the average income was approximately $2,000 a year, La Gatta was making $100,000 a year — more than the president of the United States. He bought a home and a studio in Manhattan along with another studio at Sands Point. To top it off, he built a stone manor house in the rolling countryside of Woodtsock, New York. There he and Florence held delightful weekend parties for friends, with the assistance of their chef, their butler and their chauffeur.

But perhaps the greatest symbol of their newfound wealth was La Gatta’s new 42-foot yacht, named “Deuces Wild.” He hired a full-time live-in ship’s captain to keep the yacht stocked with food and fuel so that, on a moment’s notice, La Gatta and his wife could invite friends to join them on a cruise for a few days. They would sometimes go up the Hudson River to the Woodstock Manor or to Cape Cod or Fishers Island. La Gatta often said that his “Deuces Wild” filled out their lives the same way a wild deuce filled out a hand of poker: “She filled out our happy, gracious living for many years.”

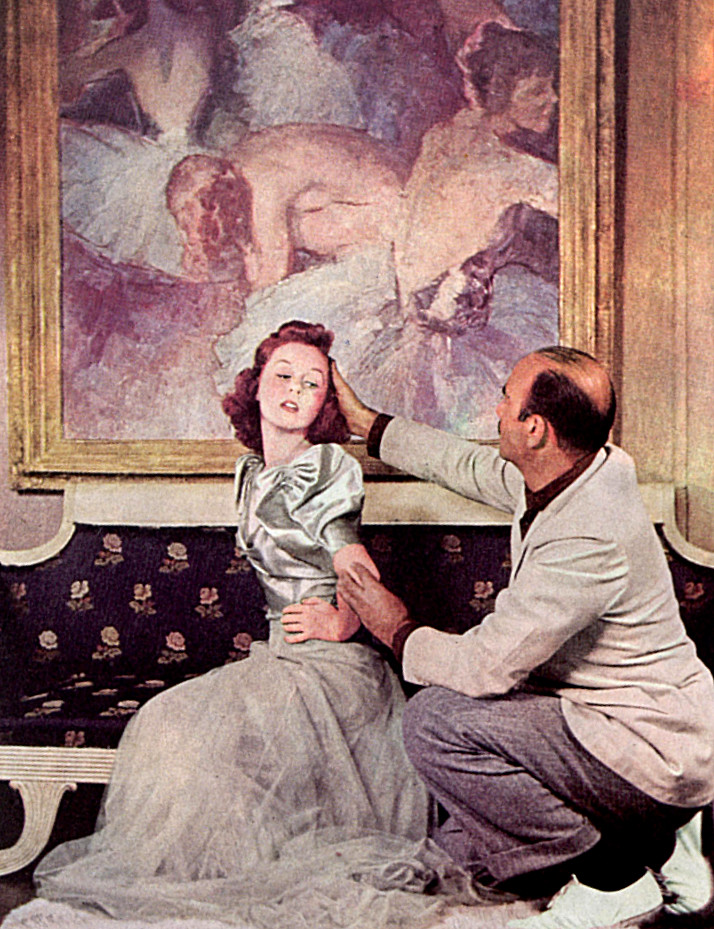

La Gatta’s colorful new lifestyle was described in Jill Bossert’s excellent biography of the artist. Illustrators in that era were famous celebrities and much in demand at social events. La Gatta would appear at hot spots such as the Kit Kat Club or attend the Cinderella Ball. As an “expert on beauty” he was called upon to select “the 50 most perfect Broadway showgirls for the 1933 movie Moonlight and Pretzels” as well as “the 16 most beautiful redheads for Hot and Bothered, a 1931 Broadway Revue.”

Rather than beg for assignments, La Gatta’s problem became fending off clients who bid for his services. People tried to persuade him to take on more assignments than he felt comfortable handling. His work was highly lucrative and prestigious, but he wanted enough time to enjoy his yacht and create his own fine art. At his peak, La Gatta was paid $1,000 for a picture, and he could create a picture in a day. That meant by working one hundred days a year, he could make time for his own personal interests.

Of course, nothing lasts forever, and popular tastes changed again in the 1940s with World War II. The demand for La Gatta’s work subsided. But that’s a story for another day.

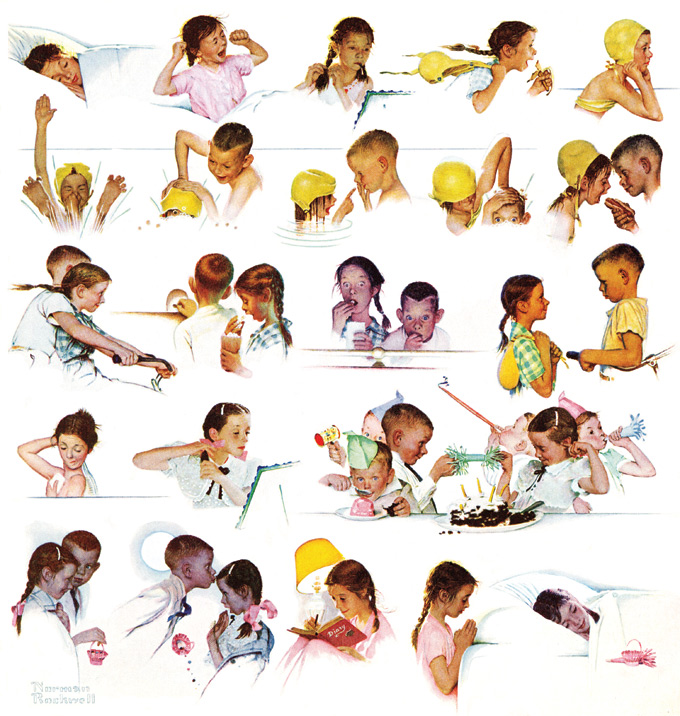

The Rockwell Files: Love at First Fight

Three months after Rockwell’s Day in the Life of a Boy appeared on the cover of the Post, he decided to document a day in a little girl’s life, too. He chose his favorite child model, Mary Whalen, to pose for the 22 images of Day in the Life of a Girl for the August 30, 1952, cover.

Rockwell had to be imaginative in posing Mary for the photographs he would use to inform the painting. To give the impression of her racing off to the pool, her mother helped by holding her pigtails back while someone else pulled on her swim cap. To simulate the mutual dunkings of Mary and co-model Chuck Marsh, Rockwell used a bronze bust. The kids posed as if to dunk the bust’s head under water so Rockwell could get their elbow angles correct.

Making Mary’s hair look soaking wet was easier: “They poured a bowl of water on me,” she said.

Now came the toughest challenge. Though the models got along when posing, Chuck absolutely refused to kiss a girl — no way, no how. He finally agreed to a compromise: Rockwell brought out the bronze bust again and photographed Chuck kissing it.

The finished cover resembled Day in the Life of a Boy except for one image. Rockwell had been criticized for not showing the boy saying his prayers before going to bed. So he removed one of the images in the sequence — Mary and Chuck thanking the birthday girl for inviting them to her party — to make room for Mary kneeling at her bedside.