“The Hobo and the Fairy” by Jack London

Jack London’s short stories in the Post concerned adventurers, criminals, working men, society folks, and — sometimes — wild animals. In “The Hobo and the Fairy,” from 1911, London tells the heartwarming tale of a homeless man and a bright-eyed, middle class child as they form an unlikely bond on a warm October’s day.

Published on February 2, 1911

He lay on his back. So heavy was his sleep that the stamp of hoofs and cries of the drivers from the bridge that crossed the creek did not rouse him. Wagon after wagon, loaded high with grapes, passed the bridge on the way up the valley to the winery, and the coming of each wagon was like an explosion of sound and commotion in the lazy quiet of the afternoon.

But the man was undisturbed. His head had slipped from the folded newspaper and the straggling, unkempt hair was matted with the foxtails and burs of the dry grass on which it lay. He was not a pretty sight. His mouth was open, disclosing a gap in the upper row where several teeth at some time had been knocked out. He breathed stertorously, at times grunting and moaning with the pain of his sleep. Also, he was very restless, tossing his arms about, making jerky, half-convulsive movements and at times rolling his head from side to side in the bum. This restlessness seemed occasioned partly by some internal discomfort and partly by the sun that streamed down on his face, and by the flies that buzzed and lighted and crawled upon the nose and cheeks and eyelids. There was no other place for them to crawl, for the rest of the face was covered with matted beard, slightly grizzled, but greatly dirt-stained and weather-discolored.

The cheekbones were blotched with the blood congested by the debauch that was evidently being slept off. This, too, accounted for the persistence with which the flies clustered around the mouth, lured by the alcohol-laden exhalations. He was a powerfully built man, thick-necked, broad-shouldered, with sinewy wrists and toil-distorted hands. Yet the distortion was not due to recent toil, nor were the calluses other than ancient that showed under the dirt of the one palm upturned. From time to time this hand clenched tightly and spasmodically into a fist, large, heavy-boned and wicked-looking.

The man lay in the dry grass of a tiny glade that ran down to the tree-fringed bank of the stream. On each side of the glade was a fence of the old stake-and-rider type, though little of it was to be seen, so thickly was it overgrown by wild blackberry bushes, scrubby oaks and young madrofia trees. In the rear a gate through a low paling fence led to a snug, squat bungalow, built in the California Spanish style and seeming to have been compounded directly from the landscape of which it was so justly a part. Neat and trim and modestly sweet was the bungalow, redolent of comfort and repose, telling with quiet certitude of someone that knew and that had sought and found.

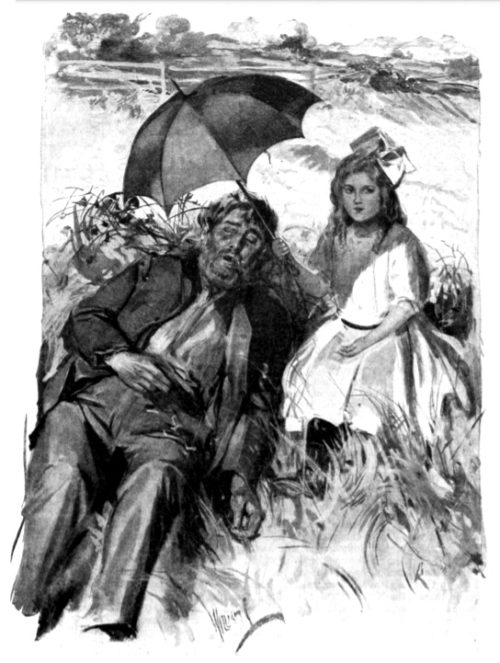

Through the gate and into the glade came as dainty a little maiden as ever stepped out of an illustration made especially to show how dainty little maidens may be. Eight years she might have been, and possibly a trifle more, or less. Her little mist and little black-stockinged calves showed how delicately fragile she was; but the fragility was of mould only. There was no hint of anemia in the clear, healthy complexion or in the quick, tripping step. She was a little, delicious blonde, with hair spun of gossamer gold and wide blue eyes that were but slightly veiled by the long lashes. Her expression was of sweetness and happiness; it belonged by right to any face that was sheltered in the bungalow.

She carried a parasol, which she was careful not to tear against the scrubby branches and bramble-bushes as she sought for wild poppies along the edge of the fence. They were late poppies, a third generation, which had been unable to resist the call of the warm October sun.

Having gathered along one fence she turned to cross to the opposite fence. Midway in the glade she came upon the tramp. Her startle was merely a startle. There was no fear in it. She stood and looked long and curiously at the forbidding spectacle and was about to turn back when the sleeper moved restlessly and rolled his head among the burs. She noted the sun on his face and the buzzing flies; her face grew solicitous and for a moment she debated with herself. Then she tiptoed to his side, interposed the parasol between him and the sun and brushed away the flies. After a time, for greater ease, she sat down beside him.

An hour passed, during which she occasionally shifted the parasol from one tired hand to the other. At first the sleeper had been restless; but, shielded from the flies and sun, his breathing became gentler and his movements ceased. Several times, however, he really frightened her. The first was the worst, coming abruptly and without warning. “How deep! How deep!” the man murmured from some profound of dream. The parasol was agitated, but the little girl controlled herself and continued her self-appointed ministrations.

Another time it was a gritting of teeth, as of some intolerable agony. So terribly did the teeth crunch and grind together that it seemed they must crash into fragments. A little later he suddenly stiffened out. The hands clenched and the face set with the savage resolution of the dream. The eyelids trembled from the shock of the fantasy, seemed about to open, but did not. Instead, the lips muttered:

“No! No! And once more, no! I won’t peach.” The lips paused, then went on. “You might as well tie me up, warden, and cut me to pieces. That’s all you can get outa me — blood. That’s all any of you-uns has ever got outa me in this hole.”

After this outburst the man slept gently on while the little girl still held the parasol aloft and looked down with a great wonder at the frowsy, unkempt creature, trying to reconcile it with the little part of life that she knew. To her ears came the cries of men, the stamp of hoofs on the bridge and the creak and groan of wagons heavy-laden. It was a breathless, California Indian-summer day. Light fleeces of cloud drifted in the azure sky, but to the west heavy cloudbanks threatened with rain. A bee droned lazily by. From farther thickets came the calls of quail and from the fields the songs of meadowlarks; and oblivious to it all slept Ross Shanklin — Ross Shanklin, the tramp and outcast, ex-convict 4379, the bitter and unbreakable one who had defied all keepers and survived all brutalities.

Texan-born, of the old pioneer stock that was always tough and stubborn, he had been unfortunate. At seventeen years of age he had been apprehended for horse-stealing. Also, he had been convicted of stealing seven horses that he had not stolen, and he had been sentenced to fourteen years’ imprisonment. This was severe under any circumstance, but with him it had been especially severe because there had been no prior convictions against him. The sentiment of the people who believed him guilty had been that two years was adequate punishment for the youth, but the county attorney, paid according to the convictions he secured, had made seven charges against him and earned seven fees, which goes to show that the county attorney valued twelve years of Ross Shanklin’s life at less than a few dollars.

Young Ross Shanklin had toiled in hell; he had escaped more than once and he had been caught and sent back to toil in other and various hells. He had been triced up and lashed till he fainted, had been revived and lashed again. He had been in the dungeon ninety days at a time. He had experienced the torment of the straitjacket. He knew what the hummingbird was. He had been farmed out as a chattel by the state to the contractors. He had been trailed through swamps by bloodhounds. Twice he had been shot. For six years on end he had cut a cord and a half of wood each day in a convict lumber camp. Sick or well, he had cut that cord and a half or paid for it under a whip-lash, knotted and pickled.

And Ross Shanklin had not sweetened under the treatment. He had sneered and cursed and defied. He had seen convicts, after the guards had manhandled them, crippled in body for life or left to maunder in mind to the end of their days. He had seen convicts, even his own cellmate, goaded to murder by their keepers, go to the gallows cursing God. He had been in a break in which eleven of his kind were shot down. He had been through a mutiny where, in the prison yard, with gatling guns trained upon them, three hundred convicts had been disciplined with pick-handles wielded by brawny guards.

He had known every infamy of human cruelty and through it all he had never been broken. He had resented and fought to the last; until, embittered and bestial, the day came when he was discharged. Five dollars were given him in payment for the years of his labor and the flower of his manhood. And he had worked little in the years that followed. Work he despised. He tramped, begged and stole, lied or threatened, as the case might warrant; and drank to besottedness whenever he got the chance.

The little girl was looking at him when he awoke. Like a wild animal, all of him was awake the instant he opened his eyes. The first he saw was the parasol, strangely obtruded between him and the sky. He did not start or move, though his whole body seemed slightly to tense. His eyes followed down the parasol handle to the tight-clutched little fingers and along the arm to the child’s face. Straight and unblinking, he looked into her eyes; and she, returning the look, was chilled and frightened by his glittering eyes, cold and harsh, withal bloodshot, and with no hint in them of the warm humanness she had been accustomed to see and feel in human eyes. They were the true prison eyes — the eyes of a man who had learned to talk little; who had forgotten almost how to talk.

“Hello!” he said finally, making no effort to change his position. “What game are you up to?” His voice was gruff, and at first it had been harsh; but it had softened queerly in a feeble attempt at forgotten kindliness.

“How do you do?” she said. “I’m not playing. The sun was on your face and mamma says one oughtn’t to sleep in the sun.”

The sweet clearness of her child’s voice was pleasant to him and he wondered why he had never noticed it in children’s voices before. He sat up slowly and stared at her. He felt that he ought to say something, but speech with him was a reluctant thing.

“I hope you slept well,” she said gravely.

“I sure did,” he answered, never taking his eyes from her, amazed at the fairness and delicacy of her. “How long was you holdin’ that contraption up over me?”

“O-oh!” she debated with herself; “a long, long time. I thought you never would wake up.”

“And I thought you was a fairy when I first seen you.”

He felt elated at his contribution to the conversation.

“No, not a fairy,” she smiled.

He thrilled in a strange numb way at the whiteness of her small, even teeth. “I was just the good Samaritan,” she added.

“I reckon I never heard of that party.” He was cudgeling his brains to keep the conversation going. Never having been at close quarters with a child since he was man-grown, he found it difficult.

“What a funny man not to know about the good Samaritan! Don’t you remember? A certain man went down to Jericho — ”

“I reckon I’ve b’en there,” he interrupted.

“I knew you were a traveler!” she cried, clapping her hands. “Maybe you saw the exact spot.”

“What spot?”

“Why, where he fell among thieves and was left half dead. And then the good Samaritan went to him and bound up his wounds, and poured in oil and wine — was that olive oil, do you think?”

He shook his head slowly.

“I reckon you got me there. Olive oil is something the dagos cooks with. I never heard it was good for busted heads.”

She considered his statement for a moment. “Well,” she announced, “we use olive oil in our cooking; so we must be dagos. I never knew what they were before. I thought it was slang.”

“And the Samaritan dumped oil on his head,” the tramp muttered reminiscently. “Seems to me I recollect a sky pilot sayin’ something about that old gent. D’ye know, I’ve been looking for him off ’n’ on all my life and never, scared up hide or hair of him. They ain’t no more Samaritans.”

“Wasn’t I one?” she asked quickly.

He looked at her steadily, with a great curiosity and wonder. Her ear, by a movement exposed to the sun, was transparent. It seemed he could almost see through it. He was amazed at the delicacy of her coloring, at the blue of her eyes, at the dazzle of the sun-touched golden hair; and he was astounded by her fragility. It came to him that she was easily broken. His eye went quickly from his huge, gnarled paw to her tiny hand, in which it seemed to him he could almost see the blood circulate. He knew the power in his muscles and he knew the tricks and turns by which men use their bodies to ill-treat men; in fact, he knew little else and his mind for the time ran in its customary channel. It was his way of measuring the beautiful strangeness of her. He calculated a grip — and not a strong one — that could grind her little fingers to pulp. He thought of fist-blows he had given to men’s heads and received on his own head, and felt that the least of them could shatter hers like an eggshell. He scanned her little shoulders and slim waist, and knew in all certitude that with his two hands he could rend her to pieces.

“Wasn’t I one?” she insisted again.

He came back to himself with a shock — or away from himself as the case happened. He was loath that the conversation should cease.

“What?” he answered. “Oh, yes; you bet you was a Samaritan, if you didn’t have no olive oil.” He remembered what his mind had been dwelling on and asked: “But ain’t you afraid?”

She looked at him as if she did not understand.

“Of — of me?” he added lamely.

She laughed merrily.

“Mamma says never to be afraid of anything. She says that if you’re good — and you think good of other people — they’ll be good too.”

“And you was thinkin’ good of me when you kept the sun off,” he marveled.

“But it’s hard to think good of bees and nasty crawly things,” she confessed.

“But there’s men that is nasty and crawly things,” he argued.

“Mamma says no. She says there’s some good in everyone.”

“I bet you she locks the house up tight at night, just the same,” he proclaimed triumphantly.

“But she doesn’t. Mamma isn’t afraid of anything. That’s why she lets me play out here alone when I want. Why, we had a robber once. Mamma got right up and found him. And what do you think! He was only a poor hungry man. And she got him plenty to eat from the pantry; and afterward she got him work to do.”

Ross Shanklin was stunned. The vista shown him of human nature was unthinkable. It had been his lot to live in a world of suspicion and hatred, of evil-believing and evil-doing. It had been his experience, slouching along village streets at nightfall, to see little children, screaming with fear, run from him to their mothers. He had even seen grown women shrink aside from him as he passed along the sidewalk.

He was aroused by the girl clapping her hands as she cried out: “I know what you are! You’re an open-air crank. That’s why you were sleeping here in the grass.”

He felt a grim desire to laugh, but repressed it.

“And that’s what tramps are — open-air cranks,” she continued. “I often wondered. Mamma believes in the open air. I sleep on the porch at night. So does she. This is our land. You must have climbed the fence. Mamma lets me when I put on my climbers — they’re bloomers, you know. But you ought to be told something. A person doesn’t know when they snore because they’re asleep. But you do worse than that. You grit your teeth. That’s bad. Whenever you are going to sleep you must think to yourself, ‘I won’t grit my teeth; I won’t grit my teeth,’ over and over, just like that; and by-and-by you’ll get out of the habit.

“All bad things are habits. And so are all good things. And it depends on us what kind our habits are going to be. I used to pucker my eyebrows — wrinkle them all up; but mamma said I must overcome that habit. She said that when my eyebrows were wrinkled it was an advertisement that my brain was wrinkled inside and that it wasn’t good to have wrinkles in the brain. Then she smoothed my eyebrows with her hand and said I must always think smooth — smooth inside and smooth outside. And, do you know, it was easy. I haven’t wrinkled my brows for ever so long. I’ve heard about filling teeth by thinking, but I don’t believe that. Neither does mamma.”

She paused, rather out of breath. Nor did he speak, Her flow of talk had been too much for him. Also, sleeping drunkenly, with open mouth, had made him very thirsty; but, rather than lose one precious moment, he endured the torment of his scorching throat. He licked his dry lips and struggled for speech.

“What is your name?” he managed at last.

“Joan.”

She looked her own question at him and it was not necessary to voice it.

“Mine is Ross Shanklin,” he volunteered, for the first time in forgotten years giving his real name.

“I suppose you’ve traveled a lot.”

“I sure have, but not as much as I might have wanted to.”

“Papa always wanted to travel, but he was too busy at the office. He never could get much time. He went to Europe once with mamma. That was before I was born. It takes money to travel.”

Ross Shanklin did not know whether to agree with this statement or not.

“But it doesn’t cost tramps much for expenses.” She took the thought away from him. “Is that why you tramp?”

He nodded and licked his lips. “Mamma says it’s too bad that men must tramp to look for work; but there’s lots of work now in the country. All the farmers in the valley are trying to get men. Have you been working?”

He shook his head, angry with himself that he should feel shame at the confession when his savage reasoning told him he was right in despising work. But this was followed by another thought. This beautiful little creature was some man’s child. She was one of the rewards of work.

“I wish I had a little girl like you,” he blurted out, stirred by a sudden consciousness of his newborn passion for paternity. “I’d work my hands off. I — I’d do anything.”

She considered his case with fitting gravity. “Then you aren’t married?”

“Nobody would have me.”

“Yes, they would — if — ”

She did not turn up her nose, but she favored his dirt and rags with a look of disapprobation he could not mistake.

“Go on!” he half shouted. “Shoot it into me! If I was washed — if I wore good clothes — if I was respectable — if I had a job and worked regular — if I wasn’t what I am.”

To each statement she nodded.

“Well, I ain’t that kind,” he rushed on. “I’m no good. I’m a tramp. I don’t want to work — that’s what. And I like dirt.”

Her face was eloquent with reproach as she said: “Then you were only making believe when you wished you had a little girl. like me?”

This left him speechless, for he knew, in all the deeps of his newfound passion, that was just what he did want.

With ready tact, noting his discomfort, she sought to change the subject.

“What do you think of God?” she asked.

“I ain’t never met Him. What do you think about Him?”

His reply was evidently angry and she was frank in her disapproval.

“You are very strange,” she said. “You get angry so easily. I never saw anybody before that got angry about God, or work, or being clean.”

“He never done anything for me,” he muttered resentfully. He cast back in quick review of the long years of toil in the convict camps and mines. “And work never done anything for me neither.”

An embarrassing silence fell.

He looked at her, numb and hungry with the stir of the father-love, sorry for his ill temper, puzzling his brain for something to say. She was looking off and away at the clouds and he devoured her with his eyes. He reached out stealthily and rested one grimy hand on the very edge of her little dress.

It seemed to him that she was the most wonderful thing in the world. The quail still called from the coverts and the harvest sounds seemed abruptly to become very loud. A great loneliness oppressed him.

“I’m — I’m no good!” he murmured huskily and repentantly.

But, beyond a glance from her blue eyes, she took no notice. The silence was more embarrassing than ever. He felt that he could give the world just to touch with his lips that hem of her dress where his hand rested, but he was afraid of frightening her. He fought to find something to say, licking his parched lips and vainly attempting to articulate something — anything.

“This ain’t Sonoma Valley,” he declared finally. “This is fairyland and you’re a fairy. Mebbe I’m asleep and dreaming! I don’t know. You and me don’t know how to talk together, because, you see, you’re a fairy and don’t know nothing but good things — and I’m a man from the bad, wicked world.”

Having achieved this much, he was left gasping for ideas like a stranded fish.

“And you’re going to tell me about the bad, wicked world,” she cried, clapping her hands. “I’m just dying to know.”

He looked at her, startled, remembering the wreckage of womanhood he had encountered on the sunken ways of life. She was no fairy. She was flesh and blood, and the possibilities of wreckage were in her as they had been in him, even when he lay at his mother’s breast. And there was in her eagerness to know.

He said lightly; “This man from the bad, wicked world ain’t going to tell you nothing of the kind. He’s going to tell you of the good things in that world. He’s going to tell you how he loved hosses when he was a shaver, and about the first boss he straddled, and the first hoss he owned. Hosses ain’t like men. They’re better. They’re clean — clean all the way through and backsgain. And, little fairy, I want to tell you one thing — there sure ain’t nothing in the world like when you’re settin’ a tired hose at the end of a long day, and when you just speak and that tired animal lifts under you willing and hustles along. Hosses! They’re my long suit. I sure dote on hosses! Yep. I used to be a cowboy once.”

She clapped her hands in the way that tore so delightfully to his heart and her eyes were dancing as she exclaimed:

“A Texas cowboy! I always wanted to see one! I heard papa say once that cowboys are bow-legged. Are you?”

“I sure was a Texas cowboy,” he answered; “but it was a long time ago. And I’m sure bow-legged. You see, you can’t ride much when you’re young and soft without getting the legs bent some. Why, I was only a three-year-old when I begun. He was a three-year-old too, fresh-broken. I led him up alongside the fence, dumb to the top rail and dropped on. He was a pinto and a real devil at bucking, but I could do anything with him. I reckon he knowed I was only a little shaver. Some hosses knows lots more’n you think.”

For half an hour Ross Shanklin rambled on with his horse reminiscences. Then came a woman’s voice.

“Joan! Joan!” it called. “Where are you, dear?”

The little girl answered; and Ross Shanklin saw a woman, clad in a soft, clinging gown, come through the gate from the bungalow.

“What have you been doing all afternoon?” the woman asked as she came up. “Talking, mamma,” the little girl replied. “I’ve had a very interesting time.” Ross Shanklin scrambled to his feet and stood watchfully and awkwardly. The little girl took the mother’s hand; and she, in turn, looked at him frankly and pleasantly, with a recognition of his humanness that was a new thing to him.

In his mind ran the thought: “The woman who ain’t afraid!” Not a hint was there of the timidity he was accustomed to see in women’s eyes; and he was quite aware of his bleary-eyed, forbidding appearance.

“How do you do?” She greeted him sweetly and naturally.

“How do you do, ma’am?” he responded, unpleasantly conscious of the huskiness and rawness of his voice.

“And did you have an interesting time too?” she smiled.

“Yes, ma’am. I sure did. I was just telling your little girl about hosses.”

“He was a cowboy once, mamma!“ she cried.

The mother smiled her acknowledgment to him and looked fondly down at the little girl.

“You’ll have to come along, dear,” the mother said. “It’s growing late.” She looked at Ross Shanklin hesitantly. “Would you care to have something to eat?”

“No, ma’am; thanking you kindly just the same. I — I ain’t hungry,”

“Then say goodby, Joan,” she said.

“Goodby.” The little girl held out her hand and her eyes lighted roguishly. “Goodby, Mr. Man from the bad, wicked world.”

To him, the touch of her hand as he pressed it in his was the capstone of the whole adventure.

“Goodby, little fairy,” he mumbled. “I reckon I got to be pain’ along.”

But he did not pull along. He stood staring after his vision until it vanished through the gate. The day seemed suddenly empty. He looked about him irresolutely, then climbed the fence, crossed the bridge and slouched along the road.

A mile farther on he aroused at the crossroads. Before him stood a saloon. He came to a stop and stared at it, licking his lips. He sank his hand into his pants pocket and pulled out a solitary dime. “God!” he muttered. “God!” Then, with dragging, reluctant feet, he went on along the road.

He came to a big farm. He knew it must be big because of the bigness of the house and the size and number of the barns and outbuildings. On the porch, in shirtsleeves, smoking a cigar, keen-eyed and middle-aged, was the farmer.

“What’s the chance for a job?” Ross Shanklin asked.

The keen eyes scarcely glanced at him.

“A dollar a day and grub,” was the answer.

Ross Shanklin swallowed and braced himself.

“I’ll pick grapes all right, or anything. But what’s the chance for a steady job? You’ve got a big ranch here. I know hosses. I was born on one. I can drive team, ride, plow, break, do anything that anybody ever done with hosses.”

“You don’t look it,” was the judgment.

“I know I don’t. Give me a chance — that’s all. I’ll prove it.”

The farmer considered, casting an anxious glance at the cloudbank into which the sun had sunk.

“I’m short a teamster and I’ll give you the chance to make good. Go and get supper with the hands.”

Ross Shanklin’s voice was very husky and he spoke with an effort:

“All right. I’ll make good. Where can I get a drink of water and wash up?”

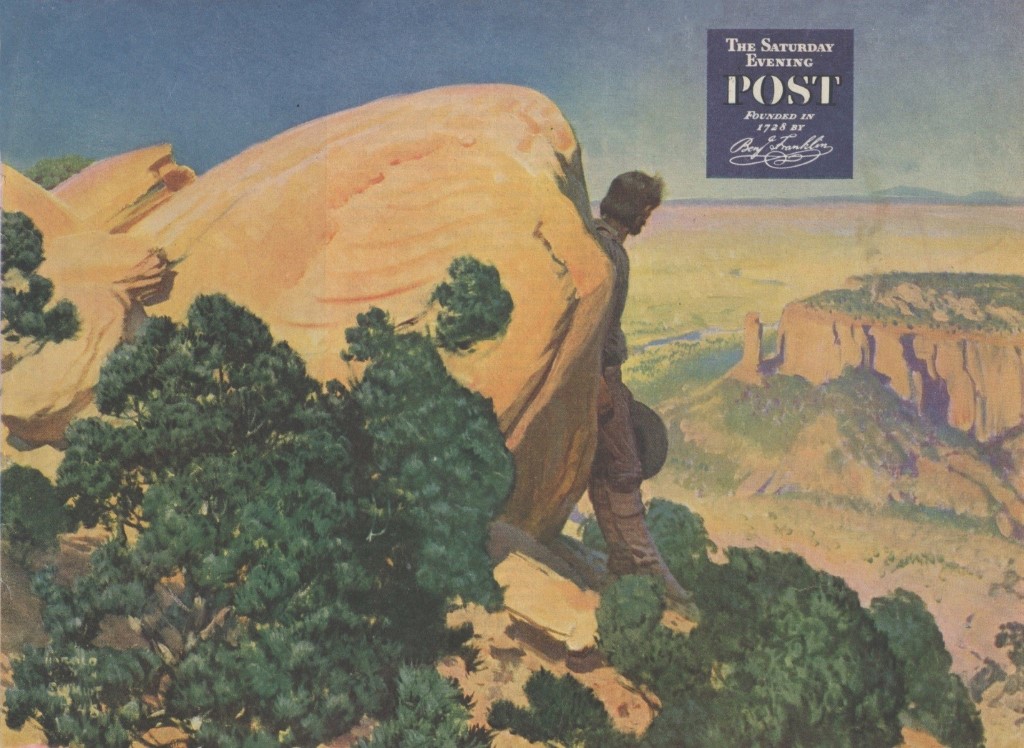

Featured image illustrated by C.D. Williams

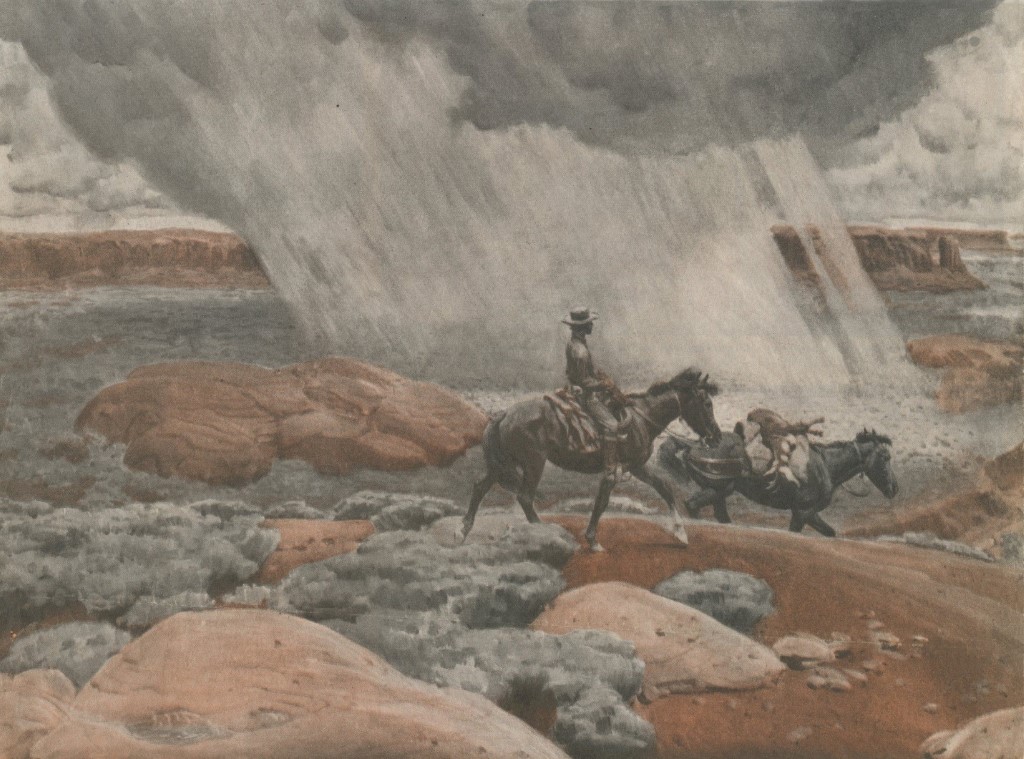

The Making of the Cowboy Myth

It is rare to find cowboys on the silver screen who spend much time performing the humdrum labor — herding cattle — that gave their profession its name. Westerns suggest that cowboys are gun-toting men on horseback, riding tall in the saddle, unencumbered by civilization, and, in Teddy Roosevelt’s words, embodying the “hardy and self-reliant” type who possessed the “manly qualities that are invaluable to a nation.”

But real cowboys — who worked long cattle drives in lonely places like Texas — mostly led lives of numbing tedium, usually on the fringes of society. They were the formerly enslaved, poor farm boys, and downtrodden Native Americans. They enjoyed little autonomy on the trail. It was Hollywood, and men like Roosevelt, who whitewashed the cowboy, elevating him to the epitome of personal freedom, manly courage, and rugged independence.

For centuries, whether in the British Isles, the Iberian Peninsula, or the Americas, herding livestock to market put meat on the tables of city dwellers and money in the pockets of rural livestock owners. “Drove roads,” the term for routes through which livestock were driven, laced the countryside of rural England and Colonial America, connecting local communities to urban centers and generating millions of dollars in trade.

Herding cattle was considered beneath the dignity of respectable people.

While turning cattle into capital could be lucrative for livestock owners, herding this “cash on the hoof” remained the job of low-status workers. In southern Appalachia during the 18th and 19th centuries, “cow keepers” used whips and dogs to control their herds, and if the term “cowboy” was used it was almost certainly pejorative. During the same era, in Mexico, the task of herding cattle fell to vaqueros, a multiracial, low-status group who transformed what had been a pedestrian chore into an equestrian art. Their lazo (rope with a slip knot) became a lasso, chaparajos became chaps, and sombrero became the ten-gallon hat. Because vaqueros were largely of indigenous descent, one could say that all of these early cowboys were in fact “Indians.”

In mid-19th-century Texas, millions of cattle grazed the open range — and many Texans preferred to gather wealth in cattle, which multiplied every year, to amassing wealth in land. But the rough task of gathering and herding cattle was considered an occupation beneath the dignity of respectable people. Herders roamed the mesquite thickets, coastal savannahs, and brush lands of eastern Texas capturing and branding any cattle they could find, seldom bothering to determine an animal’s ownership before taking it to market. Texas newspapers warned against “this roving class of worthless characters” who “may forget that there is a distinction between ‘mine’ and ‘thine.’”

Things changed after the Civil War when Texans began driving longhorn cattle hundreds of miles to the railroads in Kansas, in what became the longest, largest forced migration of animals in history. In Texas a steer might sell for only a few dollars; in Kansas, where livestock could be transported by rail directly to stockyards in Chicago, it might bring $30 or $40.

Texans who could marry their backcountry herding skills to the entrepreneurial demands of the Gilded Age stood to make fantastic profits. Some of these successful Texas cowboys became leading symbols in the new Western myth. Charles Goodnight found instant fame when he teamed with renowned cattleman Oliver Loving, hired a crew of impoverished ex-Confederates and a formerly enslaved person named Bose Ikard, and pushed a herd through the west Texas desert into New Mexico and then north to Denver. Selling the animals at $60 per head, he returned to Texas with $12,000 in gold.

Still, what actually occurred on these long drives wasn’t glamorous. Cattle herding was no place for free thinkers or independent minds. Like any other industrial-age enterprise, the cattle drive was built around guiding principles of centralized control, monotonous routines, and a disciplined labor force. It was “systematically ordered,” as Goodnight said.

Driving two or three thousand cattle over 1,000 miles required a dozen or so cowboys, each with four or more horses, working for three to six months. The trail boss, who might be the ranch owner but was more likely an experienced ranch hand, rode ahead of the herd to control the pace and direction of travel and tolerated neither unruly cattle nor rebellious laborers. Cowboys took orders and worked for wages typically lower than skilled factory pay.

Despite the prevalence of lethal firearms and “Indian” fights in Western movies, there wasn’t much evidence of either in the actual cattle drives.

Each herder had a regular position in the herd, from lead to flank to swing to drag, with status and sometimes pay according to position. According to Montana cowboy Edward Charles “Teddy Blue” Abbott, drag riders had it the worst. Responsible for bringing along the poor, weak, or wounded animals, drag riders would end the day “with dust half an inch deep on their hats and thick as fur on their eyebrows,” Abbott said. Even worse was the dust in their lungs, which had them coughing up brown phlegm for months after the drive.

Most riders on the drives were out-of-work farmers’ sons, some as young as 12 years old, who saw the opportunity to trail cattle as both a rare paying job and a rite of passage. African-American cowboys earned less and were often required to take on more dangerous tasks. Vaqueros also worked the herds. Bosses recognized their superior roping and riding skills but paid them less than Anglo riders. A few women went up the trail, mostly as wives in wagons accompanying the herds. In 1888 a young girl named Willie Matthews disguised herself as a boy and worked, rode, and roped along with the rest of the crew.

These diverse workers, a proletariat on horseback, shared in the grinding monotony of the trail — and often said as much. According to 19th-century Kansas journalist Henry King, who interviewed many trail riders as they arrived in Dodge City, repetitious chores caused cowboys to feel “adrift on these great, vague, and melancholy prairies.” One cowboy complained, “The trip that was once so exciting and thick with adventure has come to be an unspeakably cheerless and tiresome thing.”

Even the food was monotonous: Beans and biscuits constituted the standard fare. While the cowboys were surrounded by beeves — as they called cattle destined to become meat — eating into the boss’s profit margin was not an option. According to 19th-century Kansas cattle buyer Joe McCoy, the unhealthy diet, along with a lack of tents, blankets, or even clean water, sapped the youthful vigor of cowboys and caused them to become “sallow and unhealthy” and “half-civilized only.” For some, “gloom” and “depression” descended on the crew until “conversation dwindled into monosyllables.” The legendary strong, silent type — so well known from so many classic movies — may have emerged from the unspeakable boredom of trail life.

Wearisome dullness was occasionally interrupted by the sheer terror of the stampede. Longhorns had a strong flight instinct, and a thunderstorm, an unexpected noise, or even the shake of a blanket could send them scattering. This sudden, unexpected, and seemingly aimless mass flight would shake the ground like an earthquake and crush any luckless herder caught in its path. At best, a stampede meant several days and nights of chasing after stray bunches of cattle. Combined with regular shifts of riding night duty, this meant that cowboys stayed in the saddle for three days or more. In such times coffee was not enough, Teddy Blue Abbott said. The only way to stay awake was to rub tobacco juice in one’s eyes.

For some cowboys, the hardest moments along the trail were the almost daily killings of newborn calves. Some herds were entirely steers (neutered males) headed for market, but others consisted of cattle of mixed sex, including pregnant cows. Newborn calves could not be tolerated because they slowed the herd. According to his biographer, Charles Goodnight said, “We killed hundreds of newborn calves on the bed grounds. I always hated to kill the innocent things, but since they were never counted in the sale of cattle the loss of them was nothing financially.” The duty to “murder the innocents” each morning typically was assigned to a lower-status worker, either one of the younger members of the crew or an African-American, who shot the calves dead. One such worker, Branch Isbell, became so disgusted with “being the executioner” that he swore off using or owning guns for the rest of his life.

Despite the prevalence of lethal firearms and “Indian” fights in Western movies, there wasn’t much evidence of either in the actual cattle drives. Many trail bosses required their workers to keep their pistols in the chuck wagon, for fear that gunshots would cause a stampede. A cumbersome six-shooter was heavy to wear and had no real use in most trail situations. And besides, carrying pistols in public was illegal in Texas settlements and in the Kansas cattle towns at the end of the trail.

The famous Chisholm Trail passed through Indian Territory in what is now Oklahoma, and some Native nations along the path, notably the Creeks, Cherokees, and Chickasaws, charged a fee for cattle crossing their land. Some Texas drovers claimed they fought back, and told manly stories of staring down the menace while brandishing their Winchesters. More commonly, however, they hired Native American cowboys to help herds across rivers or to find strays after a stampede. While the “Indian” threat loomed large in the Texas imagination, trail drives were marked more by cooperation than conflict.

There was one way in which actual cowboys helped forge the cowboy myth — in the downtime herders enjoyed as soon as they arrived in Kansas cattle towns. After bathing and shaving, but before heading to the saloon, they traded in their homemade trail clothes — straw or felt hats, flannel shirts, durable pants — for what some called the “working costume” of the cowboy: ten-gallon Stetsons, fancy shirts, leather chaps, star-topped boots, and sometimes a fancy pistol. Thus styled, they went to the photographer, posing for photos that wound up in newspapers, galleries, and archives across the country.

This visual legacy is about as accurate as using high school prom pictures to portray the typical attire of today’s teenager. But it made an indelible impression. Through popular culture, fictional cowboys became the antidote to worrisome urbanization and soul-killing industrialization that Gilded Age Americans needed.

Buffalo Bill Cody borrowed the image of the heroic cowboy for his Wild West shows, choosing a trail rider from Texas, Buck Taylor, to perform riding and roping tricks for his Eastern audiences. Tall, lean, and handsome, Taylor quickly became known as “King of the Cowboys,” a moniker he kept when he became the model for dime novels in the 1880s, written in as little as 24 hours and sold to millions of Eastern readers seeking escape from the regimented world of cities and factories. The books, like later Hollywood Westerns, thrived on the notion of the cowboy as individualist and gun-toting adventure hero. They had no use for the monotony and hardship of a cattle drive — the real life of the cowboys.

This article originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square and is featured in the January/February 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Mild West? A decidedly unglamorous meal of beans after a long, dreary, dusty day on the trail. For the most part, cowboys consisted of poor farm boys, downtrodden Native Americans, and former slaves. (Detroit Photographic Co. / Library of Congress)

The Art of the Post: The Genuine Cowboy Artist

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

Cowboy stories were always popular with readers of The Saturday Evening Post. Several different artists were called upon to imagine the wild west for these stories, but none painted the old west as authentically as the great Harold von Schmidt.

Von Schmidt was a “leather-skinned Westerner with a lean, tanned face, a Will Rogers cowlick and eyes that seem to be focused on the horizon,” as described in his monograph from the Institute of Commercial Art. He was born in rural California in 1893, and, after being orphaned at age five, spent his early years exploring what he called “the last of the old west.” He recalled, “I had more freedom than most boys—the freedom of being forgotten…. Tactful forgetting is a fine thing for children. Being on their own gives them the initiative to succeed in a land of free enterprise.”

On his way to succeeding, von Schmidt worked as a cowhand, a lumberjack, a mule driver and a construction worker on a dam. He went down to the Mexican border where he met Pancho Villa’s ragged bandits. He learned about cattle and horses the hard way, as a working cowboy on long trail drives.

He also broke his neck twice, as well as half a dozen other bones, and dislocated his shoulder. On the good side, he once had lunch with the real Buffalo Bill.

Von Schmidt loved to draw and often kept a sketchbook with him. One day he met the famous western artist Maynard Dixon. Von Schmidt blurted out, “I’m trying to paint. I like the things you do.” Dixon did not give art lessons, but he was looking for a model and a studio assistant. He hired von Schmidt, and they soon formed a bond that changed the direction of von Schmidt’s life.

Dixon was impressed when he saw von Schmidt’s artwork. He said, “They’re a good deal better than I was doing at your age.” He spent a year coaching von Schmidt on how to improve his work.

In 1924 von Schmidt moved to New York in the hope of becoming a professional illustrator. He took his western artifacts and his ten gallon hat with him. In New York he met his wife, raised a family and became a highly successful illustrator.

For decades he was one of the lead illustrators for the Post. He painted a wide variety of subjects, but he was most famous for his illustrations of the old west. His pictures had an authenticity that you could not get from sitting in an art school; it was the kind of authenticity that you acquire from being thrown off a horse and landing on the hard ground.

He went on to become the president of the Society of Illustrators, vice president of the Artists’ Guild, and a founding member of the Famous Artists School. In 1959, he was elected to the Society of Illustrators’ Hall of Fame.

Later in life, after von Schmidt had moved to a large home in a prosperous Connecticut suburb, he looked around and remembered, “Once, I said to Maynard Dixon, who did so much for me, ‘Maynard, I’ll probably never have any money. How can I repay you?’ Dixon answered, ‘You can paint fine pictures and pass the word along.’” Von Schmidt tried to honor that standard throughout his career.