The Illustrator’s Apprentice

Roger Morgan/Boy Scouts of America

As a boy, I loved to sit in my father’s studio listening to the scratch, scratch, scratch of his paintbrush on the stretched canvas on his easel and see the strokes of color gradually grow into pictures. He whistled while he worked — mostly Sinatra tunes, Beethoven, some Willie Nelson. And he sang Roger Miller: “Two hours of pushin’ broom buys an 8-by-12 four-bit room. I’m a man of means by no means, King of the Road.”

Dad is one of the happiest people I’ve ever met. I mean, how could you whistle for 10 hours a day and not be happy? I’m sure it’s because, even at age 87, he’s doing exactly what he has loved to do since, as a child, he began doodling pictures of the Lone Ranger, sitting in a dress factory cloth bin next to his Hungarian mother, Emma, while she sewed.

Joseph Csatari tells stories in pencil and oil paint. He is a workman illustrator and meticulous draftsman in the tradition of The Saturday Evening Post artists Norman Rockwell, Stevan Dohanos, and Al Parker, who were his friends. In a career spanning 68 years, he has made thousands of paintings, portraits, and illustrations for magazines, books, advertisements, and collectibles. His work has appeared in Boys’ Life, Reader’s Digest, McCall’s, Field & Stream, Outdoor Life, and Time, among others. His cover illustrations have sold books for Simon & Schuster, Dell, Bantam, and Pocket Books. Csatari’s ability to depict the humor and wholesome ideal of American life made him a go-to illustrator in the 1980s and ’90s for advertising and corporate branding campaigns for the Coca-Cola Company, Coleman, Nabisco, Hardee’s, Taft Broadcasting, Stern’s Miracle-Gro, Chef Boyardee, Mutual of Omaha, and, of course, the Boy Scouts of America — where his professional career began in 1953 as a “layout man” in the advertising department.

After more than eight years as art director to Norman Rockwell for his annual Brown & Bigelow Scout calendar paintings, Csatari became the second “official artist of the Boy Scouts of America” after Rockwell’s retirement in 1977. In a letter to the Boy Scouts in 1976, Rockwell wrote: “In a sense there is a strange parallel between this young man and myself. Joe Csatari, until only recently, has been Art Director of Boys’ Life. In my own youth I worked for Boy Scouts in the same capacity.”

Csatari sits in the morning light in the studio of his home in South River, New Jersey, paging through volume one of Norman Rockwell: A Definitive Catalogue. On his easel is a nearly finished watercolor painting.

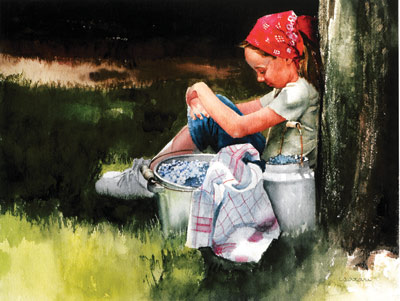

© Joseph Csatari

“I like watercolor; it’s fast and loose,” Csatari says. “As you can see, I’ve been painting a lot of ducks and horses lately. But what I really love is painting people.”

He stops flipping pages at Thanksgiving Day Blues, Rockwell’s November 28, 1942, cover for The Saturday Evening Post, showing an exhausted army chef having a smoke after preparing a 34-item meal for a brigade at Ft. Ethan Allen, Vermont.

“I remember copying this one when I was a boy,” he says. “Look at the detail in those hands. Amazing! Norman was a master of the human form.”

Csatari was 12 years old when he started copying Rockwell’s Post covers in a sketchbook. Each week, Csatari’s older brother Johnny, an aspiring artist himself, would bring home the magazine, and the two of them would practice copying the covers of Dohanos, John Falter, Rockwell, and other illustrators in pencil and oil paint.

“As long as I can remember, I wanted to paint like Rockwell,” Csatari says.

In elementary school, Csatari’s teachers recognized his proficiency early on and encouraged him. In fifth grade, he was selected to lead a crew of students to paint a 25-foot mural on the school’s walls titled I Will Prepare Myself Today, for Someday My Chance Will Come.

In high school, Csatari enrolled in the Famous Artists School, a correspondence course started by Albert Dorne and other members of the Society of Illustrators, because Rockwell was one the featured illustrators. Later, when Csatari attended the Newark Academy of Art, he took an after-hours job sweeping floors in the school’s museum so he could study the original paintings in the collection. One night, with his nose inches from a Rockwell painting, he noticed a loose paintbrush bristle stuck in a heavy stroke of paint. He plucked it, wrapped it in chewing gum foil, and put it in his wallet. He still had that purloined paintbrush bristle in his wallet in 1968, when he visited Rockwell’s carriage house studio in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, for the first time.

“Because of Rockwell’s tremendous workload, Csatari was chosen to assist him in coming up with ideas for future Scout paintings,” says Dr. Donald Stoltz, a Rockwell historian and author of several books on Rockwell. Stoltz and his brother Marshall owned the Philadelphia Norman Rockwell Museum, across the street from Independence Hall in the Curtis Building, where The Saturday Evening Post was published for many years.

Courtesy Joseph Csatari

Csatari’s task was to make preliminary rough sketches for Rockwell. When they were approved, his job intensified; he’d select models, gather props, and transport crew and equipment to the Stockbridge studio where he and Rockwell would direct photo shoots.

“They worked so closely together that they began thinking along the same lines,” Stoltz says. “Eventually, when Norman’s age started catching up with him, Norman asked the young artist to paint in some details. He really appreciated having Csatari’s help, and, of course, sitting in his mentor’s chair, using his brushes, was a huge thrill for Joe.”

On one of Csatari’s early visits to Stockbridge, he walked to The Old Corner House museum while Rockwell took his midday nap. Long before the current Norman Rockwell Museum was built, The Old Corner House displayed many of his paintings, including The Four Freedoms, large canvases illustrating the four fundamental freedoms Franklin Roosevelt outlined in his 1941 State of the Union address. “I remember feeling as if I had entered church,” Csatari says. “But then the reverence was broken when I noticed men painting the ceiling, and I worried they would spatter those glorious paintings below. I hurried to tell Norman. He just took a thoughtful puff of his pipe, smiled, and said, ‘Gee, Joe, maybe they’ll improve ’em.’ That’s how Norman was — very modest and always focused on what was the next job.”

“In a sense there is a strange parallel between this young man and myself.”

—Norman Rockwell

Csatari recognized Rockwell’s enormous talent and the value of his artwork perhaps even more than Rockwell himself, and certainly more than the critics did, during the late ’60s and ’70s. He recalls being asked in the late 1960s to transport four Rockwell paintings from a museum in central New Jersey to New York City, where Rockwell was to appear on NBC’s Today show. He placed them in his station wagon under blankets. “My teeth chattered the entire way, there and back,” Csatari says.

Upon taking over the Scout calendar commission from Rockwell in 1977, Csatari resigned as a BSA employee and began freelancing full time. He converted his garage into a studio, installing floor-to-ceiling windows to capture the northern light. Through contacts at the Society of Illustrators in New York and an agent, Csatari’s commissions grew, but slowly. With a young family to support, he supplemented his illustration income with portrait work.

Csatari’s talent for capturing a person’s image and personality on canvas became apparent in art school. While attending the Newark Academy of Art, Csatari worked from a photograph to paint a portrait of then-president Dwight D. Eisenhower. The school’s dean was so impressed with the work that he arranged for Csatari to present the portrait to the president at the White House.

“Eisenhower emerged from a meeting looking very tired when I met him, but he flashed that famous grin when he saw his portrait,” Csatari recalls. “He liked to paint, too. And he asked me if I used raw umber for the underpainting. He was right.”

© Joseph Csatari

Csatari recently learned the whereabouts of that portrait. When he left office, Ike gifted the portrait to his valet and family friend of 27 years, Johnny Moaney. Today, it remains with the Moaney family.

Csatari has painted the likenesses of Thomas Watson, Norman R. Augustine, Sanford N. McDonnell, Stephen Bechtel Jr., first lady Betty Ford, Archbishop Theodore E. McCarrick, musicians from Bing Crosby to Frank Zappa, and actors Leonard Nimoy and James Whitmore.

Portrait work filled in the gaps between illustration assignments, generally paid better than illustration did, and allowed him more liberal deadlines. “There was always something new to paint, even now, but I’m 87 and a lot slower with the brush,” Csatari laughs. Often, he had to create an illustration in just a few days — a deadline of a week or two was a luxury. For example, an art director for Time magazine once asked him to create a scene showing Jimmy Carter’s press aid and chief of staff, Jody Powell and Hamilton Jordan, dressed as Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn and whitewashing the White House fence. Csatari quickly recruited his niece’s husband to play Jordan while he himself posed as Powell. Both wore overalls and straw hats. My mother, Susan, took the photos of them in dad’s studio. The painting was finished in two days but ultimately wasn’t used due to a changing news cycle.

“As an illustrator, you had to move fast to keep up with the work when it came,” Csatari says. “And sometimes you were disappointed and had to settle for a kill fee, if you got anything at all.”

As art directors recognized his work, Csatari’s career became busier. In the late 1970s and early ’80s, longtime Post cover illustrator and fellow Hungarian Stevan Dohanos arranged for Csatari to create two U.S. postage stamps, Seeing for Me, honoring Seeing Eye dogs, and The Gift of Self, commemorating the American Red Cross. Through the 1980s and ’90s, Csatari illustrated hundreds of stories and articles for popular magazines. During this period, Csatari became a prolific illustrator of book covers, creating illustrations in oil for novels and nonfiction books by Bill Bryson, Julie Nixon Eisenhower, and Anne Baxter and for books for young readers by Paula Danziger and even Thomas Rockwell, one of Norman Rockwell’s two sons.

“I would read each manuscript and search for a high point of emotion or humor to illustrate,” Csatari says.

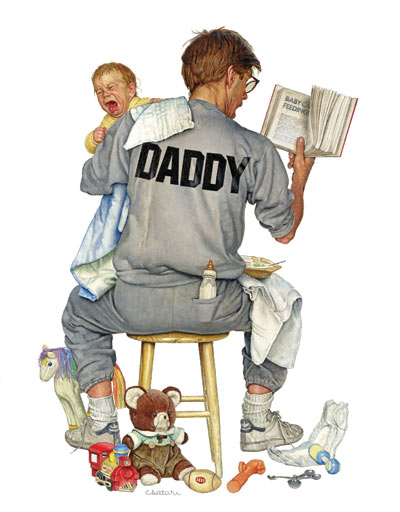

© Joseph Csatari

A book called Daddy shows a new father from behind holding his screaming child over his shoulder. Toys, rattles, and diapers are strewn on the floor, and in the father’s other hand is a book opened to the chapter “Baby Care and Feeding.”

“The problem was our baby model was so sweet and happy,” recalls Csatari, who felt he needed a wailing baby for the portrait. “She wouldn’t cry during the photo shoot. No matter what I did, she just laughed and smiled. Then the mom said, ‘Oh, wait a second,’ and she stuck her fingers in some water and flicked it in her face. Oh, geez, did that baby give me the cry I was looking for.”

Each piece of Csatari’s artwork reflects not just an image, but an impression, a story that needs to be told,” says Gail Mayfield, collections manager for the National Scouting Museum in Irving, Texas, which houses 50 of Csatari’s Scout paintings alongside those of Rockwell. Mayfield believes that while Csatari’s work is reminiscent of Rockwell’s, Csatari “developed his own personal style that reflects both the fun and service sides of Scouting with vivid color and emotion that draws viewers into his world.”

While probably best known for his Scouting illustrations, Csatari’s portraits, fine art watercolors, and cover illustrations have appeared in exhibits at the James A. Michener Art Museum, the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University, the National Museum of American Illustration in Newport, Rhode Island, and the College Football Hall of Fame. A few galleries specializing in illustration art sell his paintings, but he has never actively sought out galleries to promote his work.

Courtesy Boy Scouts of America

Currently, my father is working on his 55th or 60th — he has lost count — painting for the Boy Scouts of America. It’s a piece showing Scouts trading patches at jamboree. I’m there, modeling as a Scoutmaster. My daughter Lydia is wearing the uniform of a Venturer, the BSA’s co-ed program for teens. We’re with a couple of older Scouts watching two young guys haggling over a trade. The Scouts are in colorful printed T-shirts and high-tech khaki shorts, very different from the immaculate starched uniforms emblazoned with insignia that Rockwell painted. Dad coaxed enthusiastic faces and “big eyes” from us at the shoot. (He, like Rockwell, works from photographs.) Maybe we look a little goofy, but it’s clear we’re having fun, and that’s his goal — to make Scouting look like a lot of fun.

For Stoltz, who authored Norman Rockwell and The Saturday Evening Post, that’s what makes Csatari’s artwork reminiscent of Rockwell’s. “His characters are filled with wholesome enthusiasm,” Stoltz says. “When my wife, Phyllis, and I lecture on Mr. Rockwell’s work around the country, the most asked question from our audience is, ‘Who paints most like Norman Rockwell today?’ And the answer I give every time is ‘Joseph Csatari.’”

Though flattered, my father has always struggled with such comparisons. “Norman was in another realm with the likes of Leyendecker, Dean Cornwell, and N.C. Wyeth,” he says. “I was certainly influenced by Norman and, like him, I love to paint people.”

“Why?” I ask.

“Well, because we are all made in God’s image, and there’s something spiritual about painting people that I find so very rewarding.”

—

To learn what it was like to model for Norman Rockwell, read “A Lofty Assignment” by Jeff Csatari.