Mourning the Death of Cursive

I learned cursive handwriting in the second grade — concurrently with learning that Santa Claus was a hoax. The first word I learned to write in the august script was “Christmas.” Like a streaming ribbon across the page, the word was beautifully connected, seemingly designed to be written in one epic, fluent stroke. I scrawled a cursive “Christmas” on everything — notepads, used envelopes, a toy magnetic drawing board — like it was my own signature.

This was in the late ’90s, when the D’Nealian method of handwriting offered a smooth transition to cursive learning by way of small “tails” at the ends of t’s and i’s that would, supposedly, nudge students toward polished, fluid script. I took these tails to their elaborate limits, forming an ostentatious descender from my name’s “N” that wrapped around the word to form the tittle above the “i,” sometimes as a flower or an exploding firework. My indulgence in an ornate signature throughout grade school was an imitation of my mother’s own dramatic autograph.

I imagine such a personal connection with cursive handwriting must be prevalent among other adults who remember a time before touch screens. Cursive seems to be linked, for many, to intellectual competence, identity, and even morality in the age of its decline. We can’t imagine a functional future that doesn’t include pretty writing. But, more importantly: how could our children be deprived of the exact grueling tradition of penmanship education through which we all had to suffer?

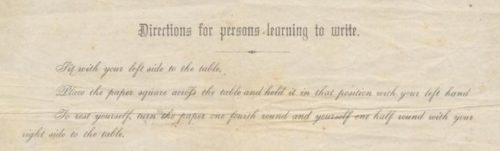

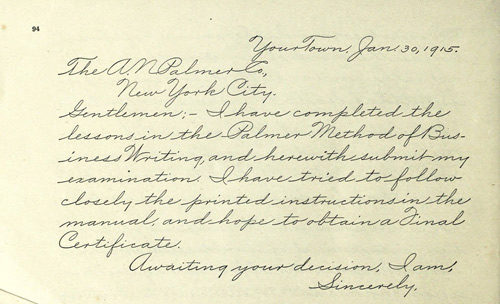

Our attachment to attached letters is rooted in our national identity. Cursive handwriting has a long, rich history in the U.S., from the copperplate lettering of the Declaration of Independence to the Spencerian script of the Coca-Cola logo. Author Anne Trubek has documented this, most notably in The History and Uncertain Future of Handwriting. The 19th century cursive school of Platt Rogers Spencer was flowery and elegant, based on the natural forms of trees and leaves, while the 20th century gave way to A.N. Palmer’s industrial age style, characterized by more rugged, efficient strokes. In a Pacific Standard article, Trubek writes, “Handwriting slowly became a form of self-expression when it ceased to be the primary mode of written communication. When a new writing technology develops, we tend to romanticize the older one. The supplanted technology is vaunted as more authentic because it is no longer ubiquitous or official.”

In 2010, the Common Core standards — detailed educational objectives encouraged by the U.S. Department of Education — omitted cursive writing from its curricula, declaring instead that students in kindergarten and first grade should learn to write in print proficiently before swiftly moving on to the keyboard. This has resulted in a years-long, nationwide debate over the usefulness of cursive script. In Indiana — one of eight states to opt out of Common Core standards — the fight for cursive is renewed each year by State Senator Jean Leising, who regularly puts forth a bill to require cursive in Indiana elementary schools. Leising notes the popularity of mandatory cursive, citing an Indiana Department of Education survey of 4,000 educators that showed 70 percent support, and rejects skeptical claims that cursive script is not a 21st-century skill. As the Indianapolis Star pointed out, Indiana Governor Eric Holcomb writes his own signature in print.

The backlash against cursive’s obsolescence has taken both melancholic and wrathful tones. In 2015, a Facebook post showed a teacher’s reprimand of a supposed 7-year-old’s cursive signature on a homework assignment: “Stop writing your name in cursive. You have had several warnings.” The post was shared over a million times and drew comments from many claiming it was a clear indicator of everything wrong with education and, perhaps, society in general. We’ve all seen mournful accounts of graduate students who can’t read historic documents or a parent’s lament that letters sent to their child’s summer camp were unappreciated. And they are in good company with the army of capitalized Facebook comments declaring cursive’s extinction “RIDICULOUS !!!” But is it?

Opinions on the usefulness of cursive sometimes focus on aspects of security: children “should, at the very least, learn their signature” or else they could be vulnerable to forgery. Marvin Sumner, a professor emeritus of Developmental Psychology at Western University, says forgery is indeed more difficult with cursive because there is “a more complicated series of motor movements involved than with block letters.” That said, the argument might be ignoring the reality of signatures in the 21st century in the first place. The familiar index-finger scribbles on coffee shop iPads hardly resemble a Spencerian autograph, and many important tasks, like filing taxes or “signing” a lease, no longer require a handwritten signature at all.

The motor movements involved in handwriting are at the heart of its benefit, whether the writing is cursive or print. Simner notes that devoting attention span to learning the construction of letters adds the motor component to visual and aural learning of language. In the Times, Maria Konnikova writes, “children not only learn to read more quickly when they first learn to write by hand, but they also remain better able to generate ideas and retain information.” Since cursive is thought to be faster, its adherents probably experience swifter and more coherent thought processes than printers, right?

The only problem is that cursive isn’t faster. In “Cursive Handwriting and Other Educational Myths,” Nautilus points to a 2013 study comparing the writing speeds of cursive French students and their printing Canadian peers. It found that, overall, cursive was slower than block print, “but fastest of all was a personalized mixture of cursive and manuscript developed spontaneously by pupils around the fourth to fifth grade.” If it isn’t more efficient, why are we perpetually trying to revive the corpse of cursive, anyway?

Could it be that the fine motor skills and neural pathways created during our taxing repetitions of loops and letterforms were accompanied by a sort of chirographic Stockholm syndrome? That we can only purge our obsessive devotion to curlicues and connected letters by passing it on to our young? With so many cursive enthusiasts in this country, you would think calligraphy was a much more universal hobby.

Like the Canadian students in the 2013 study, my own writing became a combination of print and cursive at some point in junior high. In my own signature, I traded the stylized “monkey’s tail” of a cursive “N” for a printed one with a final ascender that leaps off the page as if to say “block print can be exciting too!” When I am in the checkout line at the grocery store, however, I scratch in a sordid squiggle like everyone else.