Lucille Ball: The Making of a Comic

A 2012 People magazine poll voted I Love Lucy the best TV show of all time. But when it premiered in 1951, there was no indication it would be anything more than another forgettable, career-killing sitcom. Until then, Lucille Ball, tall and pretty, had been cast as a showgirl or trouble-making hussy. In this May 31, 1958, interview with the Post, she explained why she made the move to television and comedy:

Why TV? It really wasn’t a big decision. I was tickled to death, for two reasons: I wanted a baby and I was never very happy in pictures. Don’t get me wrong. I’m grateful for what pictures did for me. If a girl wants to be an actress and she’s paid good money for 16 years while she learns, she’s a jerk if she’s ungrateful. But with the exception of one or two pictures, I’ve never done anything I liked. You’re cast in pictures for what somebody thinks you look like, and the general idea seemed to be that I resembled “the other woman” or a colorful and too-dashing showgirl. What I felt like was a station-wagon housewife from Connecticut. I’d always leaned toward the homey bits in a script, and it was those bits that led up to I Love Lucy. That series began to take form and shape when I started having disputes with my movie studio, Columbia, about roles and finances.

When I was finished with Columbia, I had no other commitments except having a baby. Television was coming in, so I sat home with Desi, and we dreamed up I Love Lucy. I told Desi, “I want you to play my husband,” but my talent agency didn’t approve. The people there said the public wouldn’t believe I was married to Desi. He talked with a Cuban accent, and, after all, what typical American girl is married to a Latin? American girls marry them all the time, of course, but not on TV.

Unhappily, I lost that baby, and to get my mind off my loss, I said to Desi and the agency, “We’ll try out our proposed TV act in vaudeville.” We did, and the public accepted our Cuban-American marriage in spite of the doubts of the talent-agency people.

It was mostly husband-and-wife situation comedy. Mixed in with it was a little music, dancing, gags, and serious stuff. I became pregnant again, so we couldn’t continue our tour, but we were convinced we were on the right track and we sold Desi to CBS as my TV husband. I don’t remember the business details. I was pregnant and happy, and I knew I would be available eventually, and that’s all I recall.

Make ’em Laugh

Most comedy successes stem from long-standing inferiority complexes, and I had mine. My father died when I was four. Mother married again, and for seven or eight years I was with my stepfather’s Swedish parents. Until I was nine it was tough going. My step-grandparents had stern, old-country ideas. They treated other children the way I wanted to be treated, but not me. They did that to discipline me, but for me it was the wrong way to bring up a child. It gave me a feeling of frustration and of reaching-out-and-trying-to-please. I found the quickest and easiest way to do that was to make people laugh.

The principal of my school recognized my urge for approval. He saw to it that I had a part in school plays and operettas. My mother and my stepfather also encouraged me to act, dance, and sing.

When I was 14, I persuaded mother to send me to the John Murray Anderson–Robert Milton Dramatic School, in New York. I was so shy I was terrified. Bette Davis was the star pupil. I can see her now, starring in plays while I hid behind the scenery. And I took elocution, and Robert Milton made me repeat “water” and “horses” because I pronounced them “worter” and “haases.” I was so miserable mother brought me home, and I spent the next few months writing poetry.

The following summer, mother arranged for me to visit friends in New York. This time I wanted to be in vaudeville, but I never met anybody who knew how to get in vaudeville, so I decided to be a showgirl and I answered a call for an Earl Carroll tryout. I was tall and thin, but measurements weren’t the whole bit then. I rehearsed for two weeks, then a man said to me, “Miss Belmont!” (That’s who I’d decided to be.) “You’re through.” I found out later I was so young and so dumb I wasn’t contributing anything. I don’t know why they picked me in the first place.

Meeting Desi

married to Desi.

I met [Desi Arnaz] at the RKO studio in May 1940. We were filming Too Many Girls, the stage show in which Desi made his first big hit. He asked me for a date that very night, and pretty soon we were married — in spite of the way he drove a car. The first time I drove with him, although he slowed to 80 miles an hour at corners, I thought he was a maniac. When I said, “Mother wouldn’t like this,” he slowed down.

He frightened me. Marrying Desi was the boldest thing I ever did. I’d achieved some stability in Hollywood, while Desi seemed headed in another direction.

Being Pregnant on TV

In 1953, we were in the middle of a very successful TV show, which was a thing no one would want to drop. I was suddenly pregnant again and we faced the question: Should I stop working for months or stay on the job? Desi told me, “If you want my vote, we’ll stay on until you have the baby.”

The idea was a startling one, but he went to work on it. First he got permission from the network. He said, “We think the American people will buy Lucy’s having a baby if it’s done with taste. Pregnant women are not kept off the streets, so why should she be kept off television? There’s nothing disgraceful about a wife becoming a mother.” The furor it all caused was a revelation to me.

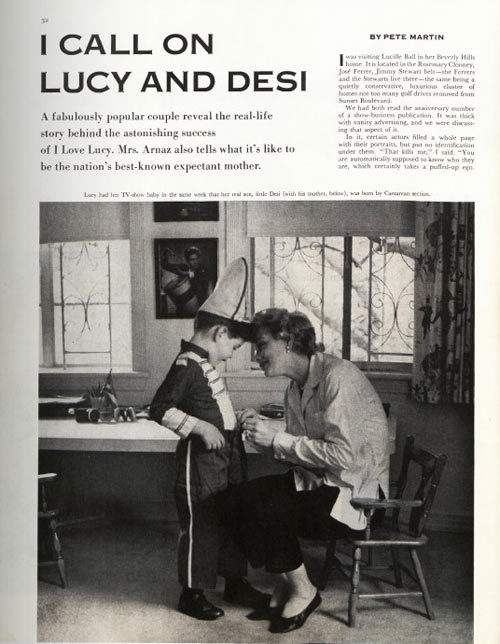

Hundreds of thousands of women all over the country who were pregnant along with me wrote me encouraging notes, and after our baby was born, I received 30,000 congratulatory telegrams and letters. Our first child, Lucy, had been born by caesarean section. Little Desi was delivered by caesarean too. If you know your baby is going to be a caesarean baby, it helps you call your shots.

[Desi Arnaz added:] “We didn’t want to do anything that would upset the public. I called the heads of the Catholic, Protestant, and Jewish faiths in Los Angeles and asked them to assign representatives to keep an eye on our shows. So for eight weeks, a rabbi, a Protestant minister, and a Catholic priest checked every foot of film we shot. There was nothing we had to throw out except the word pregnant. CBS didn’t like that, so we used expectant. CBS thought it a nicer word.

—“I Call on Lucy and Desi” by Pete Martin, May 31, 1958