Everything We Thought We Knew About Salt and Health Was Right

Unlike sugar and trans fats, we might accept salt in our food as a human necessity, an ancient mineral that conveniently boosts flavors in bland fare.

But we’ve been fed a line about sodium chloride. That’s what Dr. Michael F. Jacobson claims in his new book Salt Wars: The Battle Over the Biggest Killer in the American Diet.

For decades, Jacobson has worked with the Center for Science in the Public Interest — a group he helped found — to advocate for tighter health regulations on American food, writing a heap of books along the way advising on the science behind nutrition.

It might seem as though scientists just can’t make up their minds about the health effects of a salt-heavy diet, but Jacobson says the conflicting messages are a mix of junk science and industry deception. He argues that science has long confirmed that we consume too much salt, leading to unnecessarily high rates of cardiovascular disease, and his book tracks the half-century-long fight between “Big Salt” and health advocates — like himself — seeking to reduce the stuff in our food. Jacobson says it’s finally time to cut the salt in our food by one-third and act on the facts we’ve known all along.

The Saturday Evening Post: How do you defend the science you put forth in your book? Is there a scientific consensus that sodium consumption is too high?

Michael F. Jacobson: There has long been a consensus that we should reduce sodium intake to reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes. The consensus is reflected in statements from organizations like the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the World Health Organization, and the American Heart Association. These are not organizations that take risky positions or base their statements on flimsy evidence. Typically, in fact, they wait far too long to tell the public to do one thing or another.

In contrast, the “opposing side” — if you want to put it that way — has a comparative handful of studies that have been criticized for basic flaws from the day they were published. At this point, I hope that the debate over salt has ended. Last year the National Academy of Sciences issued a report that summarily dismissed those contrarian studies as being basically flawed. They dismissed them with a sentence, citing the other evidence that has long been mainstream.

SEP: You write about the “J-shaped curve” — the finding that lower salt intake also results in a high risk of cardiovascular disease — as the basis of a lot of these “contrarian” theories around salt. What do you make of the science behind it?

Jacobson: It’s junk. The PURE studies [Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology], which have been the most widely publicized as showing that consuming less salt could be harmful, are based on taking one urine sample from a number of participants at the beginning of the study. One sample. It’s not even a 24-hour collection, which is the standard for measuring sodium intake. The next assumption they make is that one sample is representative of a person’s lifetime consumption, but it’s not. Maybe that person ate out that day, or maybe they had cancer and were barely eating. People have long criticized that research, but in the last few years two studies completely debunked it.

Last year, the NAS did a report on sodium and cardiovascular disease. They did a meta-analysis of the best studies that involve 24-hour urine collections and found the expected linear relationship. They dismissed the PURE studies and others that found the J-shaped curve, as fatally flawed. I hope that ends the controversy.

A few years ago, Congress said the government shouldn’t take action to reduce sodium until the NAS did a study to look at sodium’s direct relationship to cardiovascular disease. Well, now they have done that study, concluding that lowering sodium is beneficial and not harmful.

SEP: How would you say that news media figures into the controversy around diet science like this?

Jacobson: I don’t understand why health journalists have given unwarranted credence to the PURE studies and their predecessors, because they’re so contrary to what the bulk of the research says. I think they, starting with The Washington Post and The New York Times, have been really irresponsible. Maybe it is an example of “man bites dog” to some extent. I bet editors love those stories that publicize the contrarian view, especially when the researchers are at respected institutions.

In the case of the PURE studies, they’re not tainted with industry funding. Rhetorically, it’s easier to shoot down studies that are funded by the snack food industry or something. But I’m really puzzled, and many other people in the field of hypertension and cardiovascular disease are shocked that those [PURE] researchers continue to get funding for that kind of research, and that respected publishers — like the Lancet or British Medical Journal — accept these studies. They certainly confuse the public.

The same phenomenon has taken place on a whole range of public health issues of great importance. With the lead industry — defending lead in gasoline — it goes back 100 years. Typically, it’s industry either sponsoring the research, or, if the research is independent, then ballyhooing the research that supports their views, saying, now government can’t act until we do studies that may be impossible to do.

With salt, there’s been a “moving of the goalposts.” Thirty years ago, the evidence was clear that increasing sodium intake increased blood pressure, and increased blood pressure then increased the risk of cardiovascular disease. Almost every researcher agreed then that raising salt increased the risk of cardiovascular disease, but after a couple of studies contrarians said that those conclusions couldn’t be coupled, that we had to prove directly, with randomized controlled studies, that raising sodium increases the risk of cardiovascular disease. Those studies are almost impossible to do. A few studies (I mention them in Salt Wars) provide some evidence, but they’re all limited in one way or another. But the American Heart Association and the WHO and others say that that research is totally unnecessary, they are certainly not funding the research, and we have far more evidence than we need to call for policies to reduce salt in the food supply and diet.

The thrust of the bulk of the field is to say, let’s reduce sodium throughout the food supply to “make the healthy choice the easy choice.” There are studies showing that if you start with lower-sodium foods and add salt, you’ll generally end up with less salt than what we see in most of our foods now.

SEP: You’ve been involved in health advocacy for many decades. What have you seen change in industry and policy as far as the American diet is concerned?

Jacobson: With salt, the policy battles began in 1969 when the White House Conference on Food, Nutrition, and Health said that sodium in the food supply should be lowered. At that time, and currently, the Food and Drug Administration considers salt to be “generally recognized as safe,” and could be used in any amount. But on the basis of the existing research back in 1978, we [Center for Science in the Public Interest] petitioned the FDA to adopt regulations to lower sodium, and top researchers supported the petitions.

A few years later, the FDA in the Reagan administration was headed by a hypertension expert, and he said that we should lower sodium by taking a voluntary approach and that if industry didn’t lower sodium, he would mandate it. That commissioner left the agency after two years, and meanwhile industry did next to nothing. Then, CSPI focused on getting sodium labeling on all foods, and we helped get the nutrition labeling law passed, which mandated labeling like the Nutrition Facts labels that list sodium on all packaged foods. So we waited to see whether labeling would reduce sodium intakes, and when I looked at it 10 years later I saw that, no, it didn’t seem to have any effect. Sodium consumption stayed the same. So in 2005 we re-sued the FDA and filed a new petition. By then, the evidence was far greater that sodium boosted blood pressure. But the government did nothing. So we then succeeded in getting Congress to fund the NAS to do a study on how to lower sodium intakes.

In 2010, the NAS published a landmark report saying the FDA should mandate lower sodium levels in the food supply, but the FDA commissioner immediately said they would push again for voluntary reductions. It took a while — six years in fact — for the FDA to come up with voluntary targets for lowering sodium in packaged foods. That was in June 2016, just months before the Obama administration left office, so clearly there was not enough time to finalize those targets.

Four years later, the Trump administration still has done nothing. Absolutely nothing. Although, two years ago, the FDA commissioner Scott Gottlieb — who’s been in the news about COVID-19 — said that reducing sodium is probably the single most important thing the FDA could do in the nutrition world. Unfortunately, he left office a few months later and the FDA did nothing.

It’s been 10 and a half years since the NAS called for mandatory reductions in sodium, and the last time that the CDC looked, in 2016, there had been no change in sodium intake in 30 years. At this point, I think the most we can hope for is the implementation of those voluntary targets. The FDA chose targets that would lower sodium to recommended levels — if all food manufacturers complied, which they won’t — in 10 years. In 10 years, a lot of people are going to be dying unnecessarily.

SEP: What was the Salt Institute? Would you characterize it in the same way that people think of the tobacco lobby or the oil lobby?

Jacobson: Steven Colbert said that the Salt Institute shouldn’t be confused with the Salk Institute, because the Salk Institute cures polio while the Salt Institute cures hams. That got a laugh from the audience [when Jacobson was a guest on Comedy Central’s The Colbert Report in 2010]. The Salt Institute was long a lobbying group set up by salt manufacturers, like Morton Salt and Cargill.

In the book I call it “the mouse that roared.” It was a small organization — five or six staff members and an annual budget of about three million dollars — but they were real tigers when it came to defending salt. Any time people criticized sodium levels in the food supply and recommended changes, the Salt Institute would be out there with vitriolic statements, pamphlets, interviews. They generated a large amount of press that I think contributed significantly to muddying the waters. They made much of that J-shaped curve theory, that reducing sodium dramatically could actually increase the risk of heart disease. But in March of 2019, they abruptly went out of business, and no one, to my knowledge has explained why.

SEP: Since the Salt Institute has disbanded, do you see an opening for salt regulation?

Jacobson: Well, the Salt Institute was never the real powerhouse. The major player was the mainstream food industry, including Kellogg’s, General Mills, McDonald’s — all the big companies, through their trade associations, and especially the Grocery Manufacturers Association. The industry kind of begrudgingly went along with voluntary reduction, but when the FDA proposed action, they nitpicked almost every single number in the FDA’s proposal. The butter and cheese industries wanted their products entirely dropped from the plan. Surprisingly, at the beginning of 2020, the Grocery Manufacturers changed its name [to Consumer Brands Association], changed its focus away from nutrition labeling and nutrition issues in general. The two main lobbying groups essentially withdrew from the playing field.

That certainly should make it easier for the government to take stronger action on sodium. But will it? I don’t know. Many of those big companies will lobby on their own. The snack food industry has SNAC, frozen food companies have the Frozen Food Institute, pickle makers have Pickle Packers International, restaurants are defended by the National Restaurant Association, and the meat industry has the North American Meat Institute. It’s hard to know how the disappearance of those two groups will affect things but making progress won’t be a cakewalk.

Between voluntary and mandatory approaches, the voluntary approach rewards companies that don’t do anything. I talked to one official at Kraft Foods, and he said that Kraft has tried to reduce sodium, but its competitors didn’t, so Kraft felt it had to go back and restore the salt. The advantage of mandatory regulation is that it provides a level playing field for companies that want to do the right thing.

SEP: Looking at the whole scope of the last 50 years or so, what would you say makes it so difficult for the U.S. to make and pass policy regarding dietary health?

Jacobson: It’s the power of industry. But also, much of the public sees a smaller role for government compared to countries in Europe, for example. Here, we have a culture of “rugged individualism.” There’s a feeling that people can lower their sodium intake if they want, a much more voluntary, individual approach.

In contrast, the British government, in the mid-2000s, adopted recommendations to lower sodium and backed that up with a pretty aggressive public education campaign. Then they used the bully pulpit to press industry to lower sodium. Within five years, the UK achieved a 10 to 15 percent reduction in sodium intake, compared to a goal of 33 percent reduction. But after a change in government, the new government lost interest.

Chile, Mexico, Israel, and a couple of other countries have passed laws requiring warning notices on packaging when foods are high in calories, saturated fat, sodium, or sugar. These are put on front labels and are very noticeable. In Chile, the law has been in place long enough to measure some results. There have been a significant number of products that have lower sodium, sugar, or fat content to escape those warning labels. That has been the most effective policy I know of to lower the sodium content in foods and presumably to lower sodium intake.

SEP: Have we seen better health outcomes in Chile as well?

Jacobson: It’s too early to know. Something like cardiovascular disease takes so long to show up. There are also so many other things going on in Chile that come into play.

SEP: Do we see sodium affecting communities differently in the U.S.? For instance, African-American communities?

Jacobson: African Americans seem to be more salt-sensitive than whites. They also have higher rates of hypertension. African-American women have much higher rates of obesity. So, when you couple obesity with hypertension, that’s a formula for cardiovascular disease. But every subgroup of the population ends up with hypertension. By the time Americans are in their 70s and older, 80 to 90 percent have hypertension. That’s why people should lower their sodium intake, lose weight, and avoid too much alcohol, to avoid gradually increasing blood pressure.

SEP: What would a lower sodium diet look like for a lot of people?

Jacobson: Packaged foods and restaurant foods would be lower in sodium. At restaurants, portions would even be smaller. There would be little effect on taste. Let me remind you that no one is saying that industry should eliminate all salt. Rather, it’s lowering salt as much as possible without destroying the taste of the food, and maybe replacing some of the salt with flavorful ingredients.

Using less salt is the cheapest, easiest thing to do. Another way is to replace salt with potassium salt. It doesn’t taste as salty, but it helps counteract the blood pressure-raising effect of a high-sodium diet. Companies can also add more real ingredients and herbs and spices. For home chefs, McCormick, Chef Paul Prudhomme, and Mrs. Dash sell salt-free seasonings. The classic study is the DASH-sodium study. It’s a randomized controlled study — the best you can do — done by researchers at Harvard, Johns Hopkins, and elsewhere. They lowered sodium by one third, from 3,400 mg, the current average daily intake, to 2,300 mg, the recommended intake, and they found that people consuming the 2,300-mg level of sodium liked the food even more than the higher level! So, I think concerns about taste are completely overblown. People quickly get accustomed to less-salty foods.

SEP: What are some personal decisions that people can make to decrease their sodium intake?

Jacobson: Sodium levels in the food supply will not drop to healthy levels instantly, no matter what the FDA does. In the meantime, consumers have to protect their health. When you’re eating processed foods, you should compare labels, because there is wide variation among different brands of the same or similar foods. Swiss cheese has one-fifth or less of the sodium in American cheese, and you can make a perfectly good sandwich with Swiss cheese. For that sandwich, you can also choose a lower-sodium bread. Bread, because we consume so much of it, turns out to be one of the major sources of sodium. You can make lots of modest changes to achieve major reductions in sodium.

We should also be cooking more natural ingredients from scratch. That invariably results in lower-sodium foods, because we’re controlling the salt. The third thing is to eat out less often. Restaurant foods have huge amounts of sodium, especially table-service restaurants like IHOP or Chili’s. That’s partly because the portions are enormous. The more food you eat, the more sodium you consume. From a chef’s point of view, the two magical ingredients are salt and butter. And it’s not just chain restaurants. Chefs have generally not been trained to lower sodium. The best thing you could do is to cook at home from scratch using lower-sodium recipes.

I mentioned how some companies are using potassium salt, and consumers can use it too. Look for “lite salt” at the supermarket. Morton and other companies sell this, and half of the table salt has been replaced by potassium salt, so you automatically cut back when you’re cooking or sprinkle it on your meal.

SEP: Looking back at the last year of presidential debates, moderators always ask a question about the biggest issue facing Americans, and I’ve never heard a candidate say that it’s salt. So, what would you say to people who think we have bigger problems and salt just isn’t that important?

Jacobson: We do have other pressing problems. Tobacco is killing a lot more people than salt. But high-sodium diets are killing tens of thousands of people each year. Health economists and epidemiologists estimate that if we can cut our sodium intake by one-third to one-half, that would prevent 50,000 to 100,000 premature deaths every year. We’re seeing the same thing around the world, where high-sodium diets are causing more than one million deaths a year. I see salty diets as the cause of a pandemic.

We have to deal with COVID-19, that’s the immediate pandemic. High-sodium diets are harmful over a longer time frame. But our society really needs to take these problems seriously even though the deaths are not immediately linked to the cause. An airplane crash kills 300 people and that gets a lot of attention, and it should. But with public health crises, where deaths are less easily associated with the cause, solving the problem is easily postponed, especially when industry stands to gain by not solving the problem. High-salt diets are absolutely something that political leaders need to address.

Featured image: © 2020 The MIT Press, Photo by Chris Kleponis

Your Health Checkup: Fasting for Better Health

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Bear’s Promise.

I usually have a banana or yogurt and coffee for breakfast, a sandwich for lunch, and eat dinner around 7 p.m., so the longest I go in between eating is six or eight hours.

Many religions, including Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, Judaism, and Hinduism, practice some sort of dietary fasting that can last many hours or days, often with participants eating at night. So, for example, fasting can occur during Lent for Christians, Ramadan for Muslims, and the holy day of Yom Kippur for Jews.

While such fasting is performed for religious reasons, caloric restriction can increase health and lifespan. Intermittent fasting appears to duplicate these benefits. Recent information indicates not eating for 16 to 18 hours — that is, consuming a full day’s intake of food over a 6-8-hour period — can beneficially impact health by triggering the body to make a metabolic switch from burning glucose to metabolizing ketones for energy.

It happens like this: glucose and fatty acids are the body’s main sources of energy. After we eat, glucose is metabolized, and fat is stored in adipose tissue as triglycerides. When we fast, the stored triglycerides are broken down to fatty acids and glycerol. The liver converts the fatty acids to ketone bodies, which then provide the major source of energy for many tissues, especially the brain.

This means that in the fed state, blood levels of glucose are high and ketones are low. When we fast, the reverse occurs, making the body burn ketones instead of glucose. Repeated exposure to periods of fasting results — in addition to weight loss — in lasting adaptive responses that help fight diabetes, insulin resistance, memory loss, and even cancer.

The heart and blood vessels particularly benefit with reductions in blood pressure and resting heart rate; improved levels of good (HDL) and bad (LDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose, and insulin; and reduced markers of systemic inflammation and oxidative stress associated with atherosclerosis.

These metabolic shifts probably began with our remote ancestors for whom life was not a sedentary experience of eating three square meals a day, with snacks in between. Homo sapiens evolved while facing a more hostile environment that required hunting large distances to stalk, catch, and eat prey, while still supporting vigorous muscle strength and brain power.

Making the change to intermittent fasting can be difficult since a diet of three meals a day, interspersed with snacks, is ingrained in the American culture, and fortified by intense marketing. Switching may be accompanied by irritability, hunger, and difficulty thinking during the initial days.

Exactly how best to achieve intermittent fasting, how long the effects last, how often fasting should be done and whether shorter fasting periods achieve similar results is not clear. More research is needed before definitive diets can be offered. In addition, sex, diet, genetic, and other factors likely influence the magnitude of the effect.

One approach is reducing the time window of food consumption gradually each day, aiming for an ultimate goal of fasting 16 to 18 hours a day. In the first month, eat in a ten-hour period five days a week; for the second month, eat in eight hours five days a week; in month three, eat in six hours five days a week; and in month four, eat in six hours seven days a week.

Another tactic could be to begin with eating 1000 calories one day per week for the first month, gradually increasing to two days per week for the second month, followed by further reductions to 750 calories two days per week and so on, ultimately reaching 500 calories two days per week for the fourth month. The switch should be done with the help of a trained dietician or nutritionist.

An important word of caution is necessary since long term studies on intermittent fasting and such caloric restriction in humans are not available. Furthermore, caloric restriction may decrease resistance against some infections in animal models and may not be appropriate for all people.

For me personally, I’m not certain I can live with the caloric restrictions — I do like to eat. But maybe I can shoot for the 16-hour food hiatus by eating an early breakfast and then a late dinner. At most, I’d probably end up with 12 hours without eating, but then I trigger all the problems of eating late, just before retiring.

Oh well. I guess there’s no such thing as a free lunch.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Your Health Checkup: Cut Calories for a Better Life

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

I like to eat. That’s my problem. Despite exercising daily, I know to lose weight I must combine my workouts with dieting.

If I could cut back just 300 or so calories a day — roughly two slices of buttered white toast, or three large scrambled eggs, or a large bagel, or two glasses of red wine — I’d lose a pound in about two weeks. If I kept it up for a year, I’d shed over twenty pounds, which would be fantastic.

But even more important, a recent study found that amount of caloric reduction had a major beneficial impact on health.

In a study called CALERIE (Comprehensive Assessment of Long-term Effects of Reducing Intake of Energy) funded by the National Institutes of Health, investigators compared a group of 75 non-obese healthy participants having no dietary restrictions with 143 similarly healthy non-obese men and women (21 to 50 years old) eating whatever they wanted as long as they decreased daily caloric intake (the goal was 25 percent reduction).

The dieters reduced caloric intake by about 300 calories a day (13 percent of total calories) mainly eating the same amount of protein as before, but reducing carbohydrates and fat, and eating more fruits, nuts, and vegetables. They enjoyed an impressive improvement in health parameters beyond the 16 pounds they lost over the two years of the study. Dieters had a drop in blood pressure, body fat, cholesterol, inflammatory markers, and improved sugar control, while the non-dieters showed no change in these parameters. Dieters also reported an improvement in quality of life with better sleep, energy, and mood without significant increases in feelings of hunger or food cravings. These results are all the more impressive because the dieters were relatively young, non-obese, and healthy with normal risk markers at baseline.

While multiple studies in laboratory animals have demonstrated that caloric restriction of 10 to 40 percent extends life, there are no such studies in humans. CALERIE only hints at that possible outcome. The diet would have to be extended over many years for it to impact longevity, and therein lies the problem: dietary compliance over a long time period. That is hard to accomplish, especially with the easily available and tempting ultra-processed junk food.

One approach would be switching to the Mediterranean Diet consisting of at least two to four weekly servings of olive oil for cooking, fresh fruits and vegetables, fish/seafood, legumes (peas/beans), sauce made of tomato, onion, garlic and olive oil, white meat, and, for habitual drinkers, seven or more glasses (per week) of wine with meals. That diet has been shown to reduce heart attacks, strokes, and death from cardiovascular disease.

Since over two thousand people die each day in the U.S. from cardiovascular disease — that’s about one death every forty seconds! — the results of studies such as CALERIE and the Mediterranean Diet offer the possibility that healthy dietary choices, including caloric reduction, might help decrease cardiovascular deaths. Diminishing metabolic risk factors at a young age would have a long-term impact.

What should you do? Resist that urge for a between-meal snack, skip dessert, and avoid ultra-processed foods loaded with calories and little nutrition. A grilled salmon steak with grilled asparagus is delicious and healthy instead of a cheeseburger and fries. Reach for a handful of almonds or a piece of fruit when you’re hungry between or after meals.

Take control of your own health by controlling your diet and become your own best cardiologist. Do it now to avoid the consequences later.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Your Health Checkup: Breakfast, Diet, and Exercise

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

In my last column, I discussed the risks of eating eggs for breakfast. I hope that information encouraged readers to substitute another food, such as bananas, yogurt, or cereal and fruit, and not stop eating breakfast, since skipping breakfast entirely appears to carry its own risk.

Investigators analyzed the eating habits of a nationally representative group of 6,550 participants aged 40 to 75 years (with a mean age of 53 years, almost half males), and followed them for 17 to 23 years. After adjusting for multiple confounding factors (always a weak point in such studies), they found that participants who never ate breakfast compared with those who ate breakfast everyday had an 87 percent increased risk for cardiovascular mortality and a 19 percent increased risk for death from any cause.

The authors noted that breakfast is an important meal, but almost 25 percent of young people skip it every day. They cite a host of health risks from doing so, including obesity, lipid problems, hypertension, diabetes, and coronary and cerebrovascular disease. This study doesn’t prove causality but only an association and other factors may be important as well.

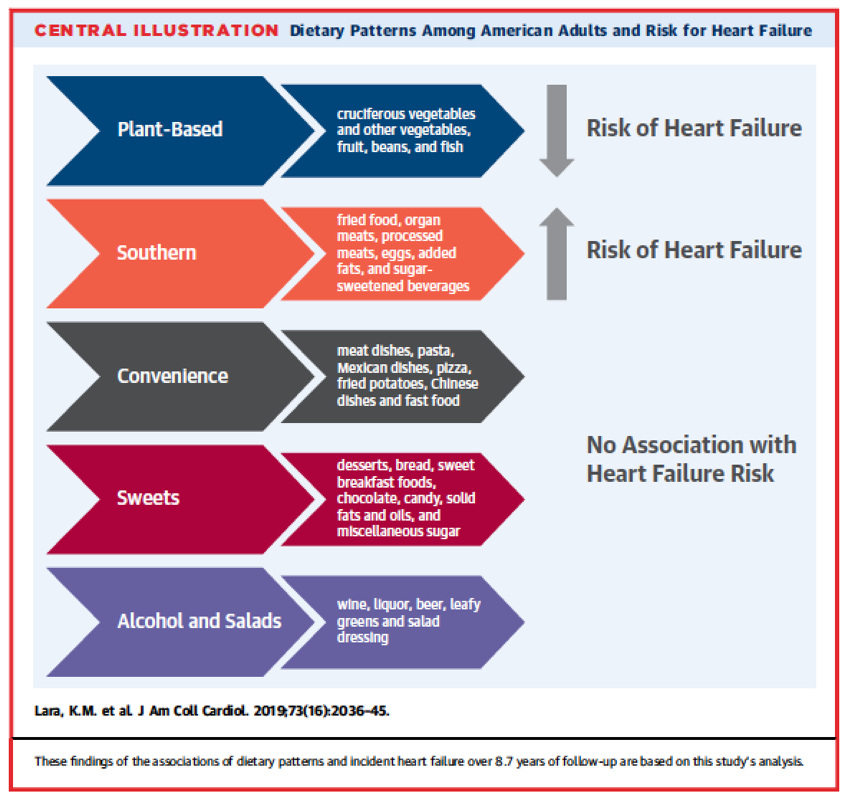

As I have stressed, what you eat is as important as when you eat. In a study of 16,068 individuals with a mean age of 64 (slightly more than half women and a third African American), the authors evaluated five types of diet: plant-based, southern, convenience, sweets, and alcohol and salads (see figure.) Those individuals adhering to a plant-based food diet including vegetables, beans, fruit, and fish enjoyed a 41 percent reduction in heart failure. Those who ate a diet loaded most heavily with fried foods, organ meats, processed meats, eggs, added fats, and sugar-sweetened beverages had a 72 percent increased risk of heart failure. The results of this study show that adhering to a plant-based diet reduced heart failure risk in a diverse population of American adults, even when they had hypertension, a known risk factor for heart failure.

Another recent study of over 400,000 men and women from nine European countries followed for 12 years found essentially the same dietary risks for red and processed meats, in this instance causing coronary artery disease (heart attacks).

And finally — I know I keep harping on it— physical activity is critically important. People can offset the impact of sitting at work all day, which is associated with an increased risk of all-cause and cardiovascular death among the least physically active adults, if they perform moderate-to-vigorous physical activity in doses that meet current recommendations.

Because walking and vigorous physical activity can most consistently reduce the risks of cardiovascular disease and premature mortality caused by sitting all day long, go do it, starting today! Walk the dog, play ball with your kids, join a fitness center, but do something!

Featured image: Shutterstock.com

Your Weekly Checkup: A New Study on Salt and Health

“Your Weekly Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Damn the Naysayers: A Doctor’s Memoir.

I don’t use a lot salt, either in cooking or on my food. My one exception is steak. A prime New York strip medium rare without salt to me is like a rose without a smell or a soda pop without a fizz. The salt makes a good taste even better.

The World Health Organization contends that most people consume too much salt, on average 9-12 grams per day or around twice the recommended maximum level of 5 grams per day. They estimate that 2.5 million deaths could be prevented annually if global salt consumption were reduced to the recommended level. They assume the salt reduction would lower blood pressure which in turn would reduce cardiovascular risk. They state that high sodium consumption ( greater than 2 grams of sodium per day, equivalent to about 5 grams of salt per day) and insufficient potassium intake (less than 3.5 grams per day) contribute to high blood pressure and increase the risk of heart disease and stroke.

Is this true? Should I switch to a low salt diet, deny myself the pleasures of a salted steak, to lower my risk of heart attack or stroke? After all salt (sodium) is an essential dietary nutrient.

Based on data from a recent study, the answer is no.

These investigators decided to test the WHO unproven assumption in the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) study of 95,767 participants (aged 35 – 70 years) in 369 communities across 18 countries whose blood pressure was analyzed. They also analyzed cardiovascular events in 82,544 participants in 255 communities. They collected a morning fasting midstream urine sample to calculate 24-hour urinary sodium and potassium excretion, and these values were used as surrogates of intake. Participants were followed at 3, 6, and 9 years (median, 8.1 years).

The mean sodium intake (sodium, not salt; the latter would be about double that value) across all 369 communities was 4.77 grams per day, higher in China than in other countries (5.58 grams per day vs 4.45 grams per day). Blood pressure increased with greater sodium intake and was associated with an increased stroke rate in China compared to other countries. Heart attacks and mortality did not increase and in fact, higher sodium intake was actually associated with lower rates of heart attack and total mortality.

PURE noted that higher potassium intake found in fruit, vegetables, dairy products and nuts was associated with reduced risk of stroke and heart attack mortality and could counter potential harmful effects of excess salt intake.

The take home message from this observational study is that that both blood pressure and stroke increase with greater salt intake, but heart attack and mortality do not. If your blood pressure is normal, there seems little reason to restrict salt intake (but don’t go crazy) as an isolated public health change and that the current salt intake in the U.S. population seems acceptable. However, if your blood pressure is high, and not brought down to normal levels by appropriate medications, salt intake should be restricted. High quality foods with increased potassium content appear to be protective and such intake should be encouraged, especially for those with elevated blood pressure.

I will continue to salt my steak and maybe my morning scrambled eggs as well.

Weight Loss Advice from the 1930s: Eat Less, Exercise More

Topping most of our resolutions this year is a repeat from the past: weight loss. But who’s to blame for this obsessive desire to trim and slim our figure? Automation? Hollywood? Feminism? France? Here’s a 1934 doctor’s take on America’s ongoing weight-loss craze:

—

Pounding Away

Originally published in The Saturday Evening Post, September 22, 1934

Before the establishing our modern knowledge of diet, it was taken for granted that the shape anyone might have had been conferred upon him by providence, and the best one could do would be to make the most of it. There was little to be done in making the least of it. Nature creates human beings and animals in all sorts of forms and sizes. A Great Dane takes many a roll in the dust, but never achieves the slimness of a greyhound; a draft horse of the Percheron type travels many a mile pulling heavy loads, but never gets small enough to be a baby’s pony. Nevertheless, the basic framework can be modified as to the amount of upholstery. Every woman knows that she can, by suitable modification of her diet and by the use of proper exercise, cause the pounds to pass away.

No one has determined certainly the cause of the recent craze for reduction. Perhaps it was the outgrowth of criticism of the female figure that was popular in the late ’90s. The textbooks of the ’90s had much to say about corset livers and hourglass shapes. The preference for the boyish form may have been the result of the gradual change in the amount of clothing worn by women. The multiple petticoats and the heavy underclothing of the late ’90s began to give way to single garments in what was called the empire style. The styles have tended toward the slim figure, covered by less and less clothing. Perhaps the change was the result of the coming of the automobile; that, too, has been a most significant factor in the change of our body weight.

A Matter of Form

Walking, up to 1900, was the accepted mode of transport for the human body in the vast majority of circumstances. Then came the motor car. Today there is in this country one motor car for each five persons, and walking is gradually becoming a lost art. Walking used to be the form of exercise primarily responsible for burning up the excess intake of food. With the gradual elimination of walking and with the coming of the machine in industry, there has been less and less demand for energy in food consumption and more and more tendency toward maintaining a slim figure by a reduction in the consumption of food. The person who takes no exercise and who eats the diet that was prevalent from 1900 to 1905 will put on weight like an Iowa hog in training for a state fair.

The suggestion has even been made that feminism was responsible for increasing the popularity of women like men. Within the last quarter century more and more women have come out of the home and into various clerical, manufacturing, promotional, industrial, and statesmanlike occupations. No doubt, the bobbing of the hair and the binding and suppression of the breasts, as well as the thinning of the figure and simplification of the costume, were women’s response to the necessity for greater ease of movement and less encumbrance while engaged in such work. A fat girl gets lots of bumps from office furniture in modern designs.

Then came the war, and with it there was intensification of all these motivations; the war made serious demands on women. The slightly suppressed desires for freedom merged into strong impulses and urges that suddenly seized every feminine mind. What had been merely a somewhat languid interest suddenly became a dominating craving. Reducing became the topic of the hour, and the craze for reduction was upon us.

It has been urged by some that the final stimulus for slenderness was a sudden change in fashions promoted by the modistes of France. Be that as it may, the French women themselves never succumbed to the craze for emaciation as did their American sisters.

The French are far too sound a race from the point of view of feminine psychology to urge the cultivation of manly traits in their women. No doubt, the French fashions did incline toward women of somewhat thinner type, but the modistes did not, like our designers of costumes, adopt an all-or-nothing policy. Individualization in form and costume has more often been the mark of France, whereas standartization and uniformity have dominated the American scene.

American manufacturers of ready-made clothing, with the beginning of the 1920s, began to produce models for slim women, hipless and bustless. As the women went into the department stores to purchase, they found it difficult to obtain anything that would fit. They came out wringing their hands and crying that most famous of all feminine laments, “I can’t get a thing to fit me.” And when a woman cannot get a thing that will fit, she is ready to fix herself to fit what she can get. There were promptly plenty of experts ready to help her through the fixing process.

To Make the Person Personable

Advertisements began to appear of nostrums to speed the activity of the body and to lessen its absorption of food. Phonograph records were sold, giving explicit instructions regarding exercise and diets. The radio poured forth systematic calisthenics and played tunes for the performance of these motions in a rhythmical manner. Plaster fell from many a living-room ceiling while women of copious avoirdupois rolled heavily on the bedroom floor. The springs and frames of many a bed groaned wearily beneath the somersaults of some damsel of 170 pounds. Pugilists who had been smacked into insensibility on the rosined floors of the squared rings became heavily priced consultants for ladies of fashion and of leisure who embarked on programs of weightlifting: Department stores offered, in the sections devoted to cosmetics, strangely distorted rolling pins with which it was claimed fat might be better distributed about the person. Shakers, vibrators, thumpers, bumpers, and rubbers manipulated electrically, by water power, or even by gas, were offered to those who cared to try them.

Out of this turmoil came a demand for a scientific study of overweight, its effects on the human body, its relationship to economics, sociology, psychology, happy marriage, the maintenance of the home, and physical and mental health. In response to this demand, research organizations in many medical institutions began to study the factors responsible for obesity and the most suitable methods for overcoming the condition without injuring the general health. Whereas, in scientific medical indexes of a previous decade, an occasional article only might be devoted to this subject, the indexes of recent years show scores of records and reports in this field.

The Do-or-Diet Spirit

The first response to the craze for reduction, as I have said, was the development of extraordinary systems of exercise, with the idea that a woman could keep right on eating the same amount of food that she formerly took and that she could get rid of the effects of this food by excessive muscular activity. Quite soon the women found out the error of this notion.

Walking 5 miles, playing 18 holes of golf, or even 6 active sets of tennis does not use up enough energy to take off any considerable amount of weight. Even the playing of an excessively severe football game removes from the body relatively little tissue. A football player, it has been reported, may be found to weigh from 5 to 10 pounds less after a football game than he weighed before, but most of this loss of weight is merely due to removal of water from the body, which is promptly restored by the drinking of water after the contest is over. Actually, the terrific strain of one hour of football burns up not more than one-third of a pound of body tissue.

Thus reduction of weight is for most people simply a matter of mathematics, calculating the amount of food taken in against the amount used up. Reduction is a matter of months and years, not of days. The investigators have shown that it is dangerous for the vast majority of people to lose more than two pounds a week. A greater loss than this places such a strain on the organs of elimination and on tissue repair that its effects on the human body may be serious and lasting.

When women found that weight could not be permanently removed to any considerable extent by excess exercise, they began to try extraordinary diets. The diets first adopted were selections of single elements. They have been characterized as perpendicular rather than horizontal reductions. The phrase refers to the nature of the diet rather than to the effect on the human form. In a perpendicular diet, the partaker eliminates everything except one or two food substances and limits himself exclusively to these. In a horizontal diet, one continues to eat a wide variety of substances, but eats only one-half or one-third as much of each. Perpendicular diets are dangerous because they do not provide essential proteins, vitamins, and mineral salts. These will be found in a properly chosen diet which includes many different foods, but smaller amounts of each. So women began eating a veal chop alone, pineapple alone, hard-boiled eggs alone, or lettuce alone. The phrase “let us alone” best expresses the proper attitude to assume toward a woman on a perpendicular diet. The constant craving for food and the associated irritability make the woman on such a diet a suitable companion only for herself, and sometimes not even for that. Certainly, she is no pleasure around a home. Among the first of the books of advice to be published on diet was one concerned only with the calories. No doubt, successful reduction of weight was easily accomplished by the caloric method, but the associated weakness, illness, and craving for food soon brought realization that there was more to scientific diet than merely lowering the calories.

The next extraordinary manifestation was the 18-day diet from Hollywood. The exact origin of this combination does not appear to be known. Perhaps it appeared first in print in the columns of criticism of motion pictures of a well-known Hollywood writer. In her statements on the subject, it was said that the diet was the result of five years of study by French and American physicians, and that the diet would be perfectly harmless for those in normal health. If the French and American doctors spent five years working out the 18-day diet, they wasted a lot of time. Any good American dietitian could have figured out an equally good combination, and probably a much better one, in an afternoon. The vogue of the 18-day diet was phenomenal. Restaurants and hotels featured it in their announcements. Hostesses, anxious to please their dinner guests, called each of them by telephone to know which day of the 18-day diet they had reached and served each guest with the material scheduled for that particular meal. It was said that a Chicago butcher bragged that he had eaten the first nine days for breakfast.

The 18-Day Sentence

The 18-day diet had peculiar psychologic appeal. For the first few days it consisted primarily of grapefruit, orange, egg, and Melba toast. Melba toast, be it said, is a piece of white bread reduced to its smallest possible proportions; then dried and toasted so as to be developed into something that can be chewed. By the second or third day, when the participant had reached the point of acute starvation, she was allowed to gaze briefly on a small piece of steak or a lamb chop from which the fat had been trimmed. Then two or three days of the restricted program followed, and again, when the desire for food reached the breaking point, a small piece of fish, chicken, or steak could be tried. Thus the addict passed the 18 days, during which she lost some 18 pounds. Then, pleased with her svelte lines, she began to eat; three weeks later she could be found at the point from which she had first departed.

For years it has been recognized that human beings need magical stimuli in the form of amulets, powders, or charms to aid in the concentration necessary for success in love, religion, health, or business. The human mind needs some single object to which it may pin its hopes, its faiths, and its aspirations. Moreover, there was the psychological appeal of mob action. There was the desire to be doing what everybody else was doing at the same time. Then there was the thrill of competition. One could hear the addicts of the Hollywood diet asking one another, “What day are you on?” And the answer came back, “I’m on the tenth day and I’ve lost eight pounds.”

With the mystic appeal of Hollywood, land of mystery, with the psychological understanding of human appetite, with the introduction of the Melba toast, the Hollywood diet swept the nation.

The Calorie Gauge

The one thing necessary to reduce weight successfully in the majority of cases is to realize just how many calories are necessary to sustain the life of the person concerned and what the essential substances are that need to be associated with those calories. Most of us enjoy our food. We eat food because we like it, and we eat without thinking what the food will do in the way of depositing fat. The researches in the scientific laboratories that have been made in the past 10 years indicate that we eat more food than we need, particularly at a time when energy consumption is far less than energy production. It has been generally assumed that the weight of the body is definitely related to health. There are standard tables of height and weight at different ages for all of us from birth to death. It must be remembered, however, that these are just averages and that any variation within 10 pounds or even 15 pounds of these averages is not incompatible with the best of health in a person who inclines to be either heavy or light in weight as a result of his constitution and heredity.

There are two types of overweight: One … in which the glands of internal secretion fail to function properly; the other … due to overeating and insufficient exercise. The glands of the body, including particularly the thyroid, the pituitary, and the sex glands, are related to the disposal of sugars and of fat in the body. In cases in which the action of these glands is deficient, a determination of the basal metabolic rate of the body will yield important information. This determination is a relatively simple matter. One merely goes without breakfast to the office of a physician who has a basal-metabolic machine, or to a hospital, all of which nowadays have these devices. One rests for approximately one hour, then breathes for a few minutes into a tube while the nose is stopped by a pinching device, so that all the air breathed out can be measured. By appropriate calculations, the physician or his technician reaches a figure which represents the rate of chemical action going on in the body. A rate of anywhere from –7 to +7 is considered to be a normal metabolic rate. A rate of anywhere from –12 to +12 may be within the range of the normal for many people. If no other special disturbance is found, the physician is not likely to be concerned about the metabolic rate within such limitations. Rates well beyond these two figures, however, are considered to be an indication of failure in the chemical activities of the body — namely, either too rapid or too slow — and measures should be taken promptly to overcome the difficulty. If the basal metabolic rate is –20, –25 or –30, the physician will prescribe suitable amounts of efficient glandular substances to hasten the activity. Moreover, he will at this time arrange to repeat his study of the metabolic rate at regular intervals. He will watch the pulse rate and the nervous reaction of the person to make certain that the effects of the glandular products that are administered are kept within reasonable limitations. If, on the other hand, the basal metabolic rate is found to be +20, +25, or +30, he will make a study of the thyroid gland and will provide suitable rest, mental hygiene, and possibly drugs to diminish this excess action. Rarely, indeed, is a person with a metabolic rate of +25 fat; in most instances, such people are thin, sometimes to the point of emaciation. There are periods in life when the human body tends to put on fat. As women reach maturity, as they have children, as they approach the period at the end of middle age, there is a special tendency to gain in weight. Men are likely to spend more time in the open air, eat more proteins and less sugar than do women, and therefore are less likely to gain weight early. The common period for the beginning of overweight is between 20 and 40 years of age; in women the average being usually around 30. Among men, the onset of overweight is likely to come on eight to ten years later.

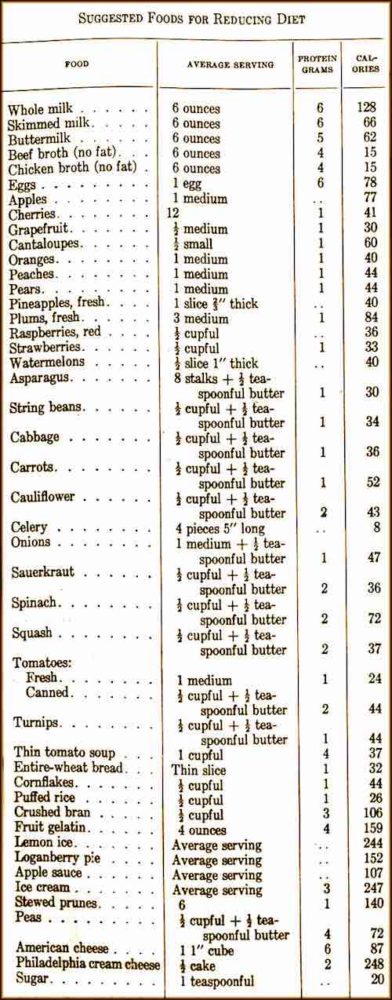

A man doing hard muscular work requires 4,150 calories a day; a moderate worker, 3,400; a desk worker, 2,700, and a person of leisure, 2,400 calories. A child under one year of age requires about 45 calories per pound of body weight, about 900 calories a day. The number is reduced from the age of six to 13 to about 35 calories per pound, or 2,700 a day; from 18 to 25 years, about 25 calories per pound of body weight may be necessary, or 3,800 a day. Thus, a person 30 years old, weighing about 150 pounds, may have 2,700 calories; a person 40 years of age, weighing 150 pounds, may have 2,500 calories; a person 60 years of age, weighing 150 pounds, may have 2,300 calories. A calorie is merely a unit for measuring energy values. In the accompanying table examples are given of the number of calories in various well-established portions of food.

Slim Picking

The overweight child at any age is quite a problem for the doctor. Most times it is the result of a family that tends to eat too much. Children of fat people are likely to be fat because they live under the same conditions as do their parents. If the adults of the family eat too much, the children can hardly be blamed for doing likewise. Investigators at the University. of Michigan say that the normal person has a mechanism which notifies him that he has eaten enough. Obese people require stronger notification before they feel satisfied, and many disregard the warning signal because they get so much pleasure out of eating. “Pigs would live a lot longer if they didn’t make hogs of themselves,” said a Hoosier philosopher.

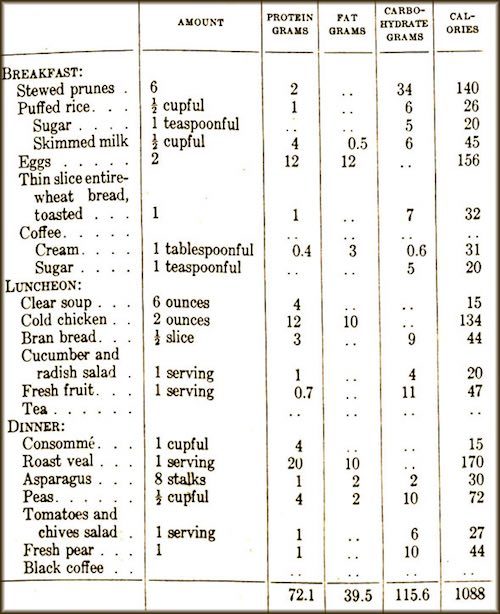

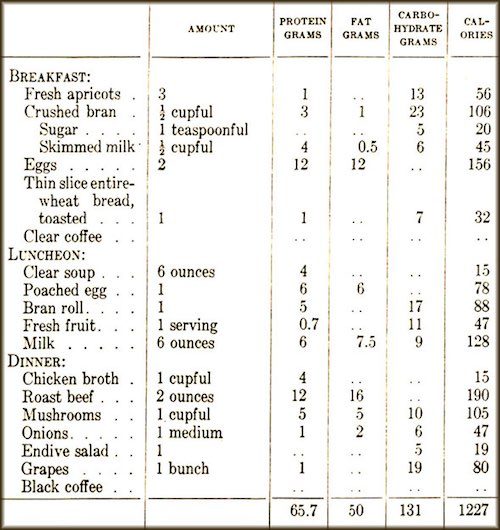

If a physician has determined that excess weight in any person is not due to any deficiency in activity of the glands, but primarily to overeating, it is safe to take a diet that contains a little more than 1,000 calories a day, and that provides all the important ingredients necessary to sustain life and health. A menu like the following, outlined by Miss Geraghty, provides about 1,000 calories as well as suitable proteins, carbohydrates, fats, mineral salts and vitamins:

For those who want to reduce intelligently, here is another menu that includes all the important ingredients:

If you simply must have afternoon tea, add in 150 calories that the sugar and accompanying wafers will contain.

Every woman who has heard of these diets insists that they provide about twice as much food as she usually eats. This merely means that she is talking at random rather than mathematically. These diets do contain a wide variety of ingredients, but they are chosen with exact knowledge of what they provide in the way of calories and important food attributes. Quite likely, the women who protest eat a smaller number of food substances, but it is likely, also, that they eat so much of each of these substances that their calories are far beyond the total. Furthermore, they probably fail to keep account of the occasional malted milks, cookies, chocolates, or ice cream that they have taken on the side.

From the accompanying table of caloric values, it is possible to select a widely varied meal that will provide any number of calories deemed to be necessary; and if the meal is selected to include a considerable number of substances, it will have all the important ingredients.

In taking any diet, it is well to remember that calories are not the only measuring stick for food. A pint of milk taken daily provides many important ingredients. If bread, potatoes, butter, cream, sugar, jams, nuts, and various starchy foods are kept at a minimum, weight reduction will be helped greatly.

Over the radio and in a few periodicals that do not censor their advertising as carefully as they might, there continue to appear claims for all sorts of quack reducing methods. If only most people had some understanding of the elementary facts of digestion and nutrition, the promotion of such methods would yield far fewer shekels to the promoters. It is a simple matter to get rid of excess poundage and, in general, it is quite desirable. One merely finds out first how many calories per day constitute the normal intake, and tries to get some idea of the number necessary to meet the demands of the body for energy. One selects a diet which provides the essential substances and which permits some 500 to 1,000 calories less per day than the amount required.

Under such a regimen, steadily persisted in, the fat will depart from many of the places where it has been deposited, but not always from the places where it is most unsightly. For this purpose, special exercises, massage, and similar routines may be helpful. But persistence more than anything else is required. It is just a matter of pounding away.

7 Wackiest Fad Diets

Do you find yourself longing for a return to the health and vitality of your salad days without the need for literal salad days? The best way to lose weight healthfully is with a gradual lifestyle change to a balanced diet and regular exercise, but where’s the fun in that? These fad diets promise mostly speedy results with little or no exercise, and we will eat our hats if they actually work.

- Cabbage Soup Diet: Since the 1980s, this scheme to shed pounds quickly has been ubiquitous in the diet world. A cabbage soup made of vegetables and broth is consumed for seven days, along with strict daily allowances of produce, milk, and beef. The low-calorie eating will likely prompt swift weight loss, but don’t expect to keep the pounds off. Unless you’re obsessed with cabbage, the diet will be difficult to sustain.

- Blood Type Diet: Naturopathic physician Peter D’Adamo insists that the answers to wellness and fitness can be found in a person’s blood type. He has been insisting for over 20 years that appropriate diets can be recommended for people based on ABO blood groups. Of course, scientific evidence for this claim is nonexistent, It is the impression of individualization, perhaps, that affords blood type diet franchises their success. Our attitude toward this diet is B-negative.

- Moon Diet: If it is true that a full moon correlates with aggressive behavior, perhaps all of the late-night lunatics are following this diet. Also known as the “werewolf diet,” this fad relies on the supposed power of the moon to stimulate weight loss. Proponents of this far-out regimen allege that fasting with juice and water for 24 hours during a full moon will take advantage of some undefined tidal effect on the human body. The moon diet can also be attempted during a new moon — and probably at any time waxing or waning as well. This fad diet eclipses the rest in terms of New Age nuttiness.

- Grapefruit Diet:

James Cagney turns a grapefruit into a weapon in The Public Enemy (1931), Warner Bros.This trend of unknown origins involves eating grapefruit along with proteins and fats such as eggs, bacon, and fish. Incarnations of the grapefruit diet are typically low in carbohydrates and starches. The surprising part? It might actually work. A 2014 study found that a similar diet in mice resulted in less weight gain and healthier blood glucose and insulin levels. As long as you aren’t taking a medication that interacts with grapefruit dangerously, the bitter citrus can be a great addition to your balanced diet.

- Detox Diet: Although detoxification is a process carried out by the liver and kidneys — or a medical team in instances of poisoning — cleanse or detox diets advise a period of fasting accompanied with daily saltwater, lemonade, and laxative tea to rid the body of toxins and promote weight loss. Perhaps the most famous of these is The Master Cleanse, in which adherents guzzle a concoction of lemon juice, cayenne pepper, and maple syrup for 10 days. Harvard Women’s Health Watch warns against detox diets, saying that a “daily laxative regimen can cause dehydration, deplete electrolytes, and impair normal bowel function.” Since no evidence exists to suggest these diets will actually detoxify your system, we’re going to skip the spicy lemonade.

- HCG Diet: Human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) was found in weight loss supplements that were made illegal for over-the-counter use in the U.S. in 2011. The hormone is found in the placenta of pregnant women, and it was first used for weight loss in the 1950s. The most alarming aspect of the HCG diet plan is the daily intake of just 500 calories. This kind of extreme dieting is broadly rejected by doctors and scientists as hazardous behavior.

- Raw Food Diet: A raw diet might conjure images of a 1960s health food cult with a charismatic leader and strict rules about

The source family of 1960s L.A. vegan notoriety. (Isis Aquarian) yeast, but The Source Restaurant in Los Angeles was just the beginning of this culture in the U.S. A raw, vegan diet consists of fruits, vegetables, grains, legumes, and seeds that have not been heated above 104 degrees Fahrenheit, since raw foodists insist that heating food diminishes its nutritional and digestive values greatly. This is true of some foods; but others, like tomatoes, asparagus, and mushrooms, release nutrients and antioxidants only when cooked. Meal preparation for a raw diet can be costly and time-consuming as well, rendering fresh, natural eating unrealistic. With daily processes like dehydration, seed-sprouting, and fermentation, reaching a healthy level of calories and fats can be a full-time job. This is a diet either for those who can afford to outsource the harvest or for folks who have spare time on the commune.

Also be sure to read Managing the Hunger Mood from the March/April issue.