A Perfect Childhood

When I was a kid, everything essential to life could be found on our town’s courthouse square. Lemmy Chalfant was the town plumber. His shop was next door to the bank, just north of the Buckhorn Bar, near the dry cleaners, which was beside the post office and across the street from the Hoosier Hotel, alongside the Coffee Cup Restaurant, beside the Johnston’s IGA, across the alley from the office supply store, catty-corner from Baker’s Hardware and Money’s Television and Radio, just down from the Royal Theater and Lawrence’s Drug Store, beside the town’s other bank, across Main Street from Dinsmore’s Basket Shop, which was east of Mingle’s dress shop and Thompson’s Rexall, next to Beecham’s Menswear, down the block from Danners’ five-and-dime.

In the basement underneath the Hoosier Hotel was Floyd’s Bicycle Shop and John Foster’s barbershop. John Foster was one of three barbers in town, none of whom had the least bit of talent in matters tonsorial. Every man in town had tufts of hair sprouting amidst shorn flesh, like a dog with mange who had scratched itself raw. In our town, if a man failed at every other venture, he became a barber in order to share his misery with others.

As town squares go, ours was a doozy, so of course it could not last. The stores died one by one, replaced by law offices, except for the Royal Theater, which has enjoyed a resurgence, and The Republican newspaper, whose editor is a Unitarian democrat.

Of all the stores now gone, I miss Danners’ five-and-dime the most. It sold, among other wonders, hairnets, penny candy, lampshades, and parrots who had been taught to cuss by our town’s juvenile delinquent, Ronny Millardo. His very name was synonymous with wanton depravity. Even the Quaker pastor, who loved everyone, despised Ronny Millardo. Continuing his early penchant for hanging around the ethically suspect, Ronny Millardo moved away, went to college, became a lawyer, and was eventually elected to Congress. His mother, as you can imagine, was devastated.

But I digress.

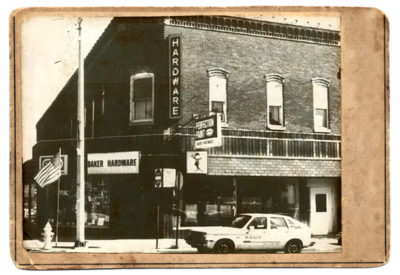

Another favorite was Baker’s Hardware, ran by Rawleigh Baker, who also owned the funeral home. We lived down the street from the funeral home and became such close friends with Rawleigh that when my sister went to college, we transported her belongings in Rawleigh’s hearse. Eighty-seven miles from our front door to Ball State University, my sister weeping in shame the entire way, her reputation in tatters the moment we drove onto campus, my father stopping at every corner to ask directions, rolling down the hearse window to introduce himself and his daughter, another proud parent paving the way for his beloved first child.

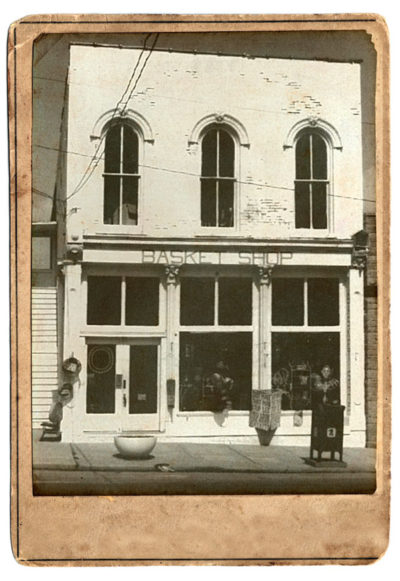

Smiley Dinsmore and his wife owned the Dinsmore’s Basket Shop. Smiley had the world’s largest false teeth, causing his lips to pull back into a permanent rictus grin, hence his nickname. Dinsmore’s had once been a grocery store and among the back shelves one could still find evidence of Smiley’s life in the food trade, mostly old cans of beans dating from the Civil War era, which Smiley had marked down to a nickel and still couldn’t sell, except to the occasional museum.

When the grocery trade dried up, Smiley switched to baskets. A hand-painted sign stood out front of the store, along Main Street. The sign should have read: “Lady, make that man stop. Let you look. See 10,000 baskets.” Smiley was a fine man, but a poor grammarian, so the sign was devoid of punctuation. “LADY MAKE THAT MAN STOP LET YOU LOOK SEE 10000 BASKETS.” By the time motorists figured out Smiley was selling baskets, they were a block past the shop and in no mood to turn around.

For four years of my childhood, I delivered The Indianapolis News, whose local office was in the basement of Mingle’s dress shop. It was Ronny Millardo who had the idea to drill a hole in the newspaper’s ceiling and peer up into the changing rooms of Mingle’s, where he saw Mrs. Miller, the school librarian, in a state of undress and fainted dead away.

It was my pleasure to deliver newspapers to nearly every business on the square—the hotel, the two lawyers, the banks, the five-and-dime, Lemmy Chalfant’s plumbing shop, and the Buckhorn bar, where I would stand at the door, not permitted to enter, so would fling the paper into the smoky depths, then cross the street to the Coffee Cup Restaurant where Mrs. Smith had a bottle of Coke waiting for me on hot, summer days. Though it did not seem so at the time, in my memory it has become a nearly perfect childhood and one I return to visit time and again in the dappled light of present days.