Titanic Fanatics

On an overcast June day in 2015, Dave Gardner, a short man with graying hair under his beanie, was intently focused on photographing the corroded archway of a long-disused Hudson River pier in lower Manhattan. As disinterested passersby ignored him, he took picture after picture, all the while simultaneously assessing possible ways to get onto the rotting pier.

A little more than a century before, an excited crowd of 30,000 people were massed right where Gardner stood now and stretching back several city blocks. They were anxiously awaiting the 705 survivors of the Titanic arriving on the ship that rescued them, RMS Carpathia.

Gardner’s a tour guide who considers it his responsibility to document Titanic landmarks in New York. Now he was paying what might be his final respects before the pier was scheduled to be demolished, to be replaced by a floating park. He was there to take what might be the last photos of the pier, but he wanted to do more.

He walked an 8-foot-tall fence, looking for a place to slip through. If he could find that, he could do it: He could save some rusted pipe, hunks of asphalt, and a few old bricks.

Suddenly he saw the word ROSE — the name of Kate Winslet’s character in the 1997 film Titanic — stamped on the side of a heap of bricks from the pier. “When I saw that,” Gardner later wrote on Facebook, “I wanted them … bad.”

In truth, it was really the manufacturer’s name. And, granted, Rose was fictional — but Gardner knew fellow enthusiasts would be thrilled to see and own these bricks, even though the original pier actually had burned down in 1932 and collapsed into the Hudson.

Gardner returned at night, slipped in, and searched through the demolition site. As he went, he shoved bricks and fragments of metal and concrete into a tote bag. He was after only the best rubble. Then he reemerged, undetected, happy to have saved something from the location where survivors might have taken their first steps on land after history’s most famous maritime disaster.

Gardner is just one of a global community of Titanic enthusiasts that runs the gamut from Leonardo DiCaprio fans to professional wreck divers. They all share a fascination with the immortal disaster, bonding over the human tragedy as well as the trappings of the Gilded Age. And today, this community is reinventing itself for social media, its leaders seeking to find ways to keep the artifacts intact and the story relevant. It’s the latest stage in the idiosyncratic history of an intercontinental subculture full of historians, amateur sleuths, self-made lecturers, and memorabilia collectors.

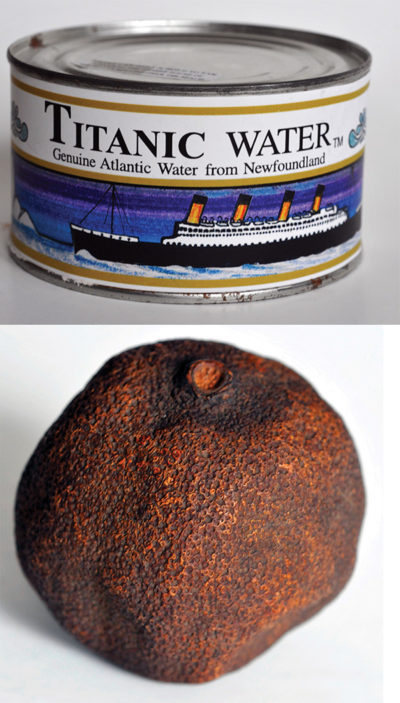

But why love the Titanic? Why this fervor for something so grim and remote? What makes people spend leisurely afternoons reading everything they can about the many who died of drowning or hypothermia? Or pay a fortune for waterlogged coal from a boat that wouldn’t float and canned saltwater that might have touched it? Or trespass to steal bricks from a pier even the city doesn’t want?

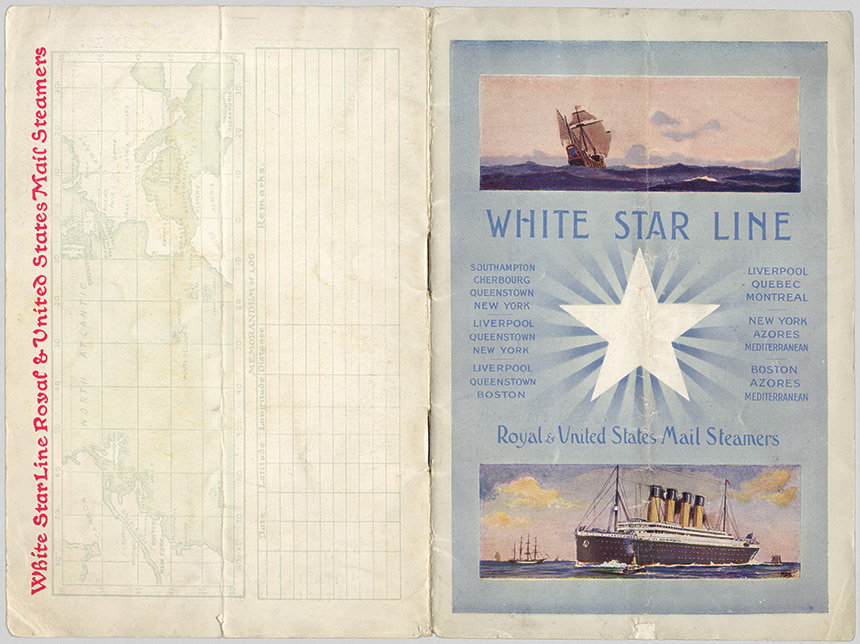

The Titanic had been the subject of international fascination even before the sinking: The shipping company White Star Line’s response to their competitor Cunard’s swift ocean liners was building ships unprecedented in size and luxury. Titanic’s grandeur and intricate system of water-tight bulkheads gained it a reputation as an unsinkable palace. So, when it struck an iceberg and sank in the North Atlantic Ocean on April 15, 1912, the public response was grand-scale shock and mourning for the 1,500 people lost on the maiden voyage.

Another reason Titanic’s story is so much more compelling than other maritime tragedies has to do with time. Consider, for example, the sinking by the Germans of RMS Lusitania, an English ocean liner, in 1915, with the loss of 1,193 people. “The problem with the Lusitania in terms of being on anybody’s radar is that the ship sank in 18 minutes. There wasn’t enough time for stories to play out and for interpersonal dramas to take place,” says historian and president of the Titanic International Society Charles Haas. “Titanic, you have two hours–plus where we see human behavior at its best and its worst.”

A Texas collector spent approximately £78,000 to own a key to the ship’s chartroom.

And since there were so many survivors of Titanic to recall in detail the incredible human dramas of those horrible final hours, the world has been captivated by them ever since as the tragedy remained etched in the public consciousness, in movies and books, throughout two world wars.

But the tale of the Titanic fans and enthusiasts begins more than 40 years after the tragedy. That’s when 14-year-old Edward Kamuda first saw the 1953 film Titanic in his family’s small theater in Indian Orchard, Massachusetts. “If the Titanic (the memory, that is, not the ship) never disappeared, its presence after 1913 was occasional or marginal until it was rediscovered for new audiences in the 1950s as a commercial phenomenon,” Steve Biel, a Harvard history professor, wrote in his 1996 cultural history of the ship, Down with the Old Canoe.

As Kamuda watched Titanic sinking in the film, with the doomed passengers singing “Nearer My God to Thee,” some emotional needle was threaded within him. According to the Titanic Historical Society, he began trying to find others fascinated by Titanic, contacting any aficionados he could through ads, articles, and mutual pen pals. Five years later, when the film A Night to Remember — based on Walter Lord’s book about the sinking — was in theaters, Kamuda used a survivor list sent with publicity packages to contact them about their experiences.

Kamuda’s efforts to create a group of enthusiasts took on greater urgency in 1963, when he learned Walter Belford — featured in Lord’s book — had died and his belongings were posthumously discarded. Kamuda was sure historic relics were lost. He wouldn’t let it happen again. (Ironically, Belford’s claim to be a Titanic survivor was a hoax.)

So on July 7, 1963, seven people embarked on a new kind of project at Ed Kamuda’s Massachusetts home: a kind of history hobbyists Ocean’s 11, composed of survivors and Kamuda’s network. The group’s newsletter carried the details: There was Kamuda himself and his sister Barbara, who provided Titanic books and films, a location, and the plan. There was Frank Casilio, with his meticulous Titanic scrapbooks. Joseph Carvalho and his wife arrived with a model of the ship he’d spent a year building. Teenager Michael Ravetti brought a collection of Titanic-related news and magazine clippings. Finally, Bob Gibbons, who couldn’t show up in person, called in from Missouri.

By early evening, the men were founding members of the world’s first group for Titanic fanatics — Titanic Enthusiasts of America (renamed the Titanic Historical Society after a survivor questioned saying they were “enthusiastic” about a tragedy). They began seeking members. Over several decades, their efforts — bolstered by the 1985 discovery of the wreck and James Cameron’s enormously successful 1997 film — resulted in a sprawling membership.

Since that time, numerous Titanic appreciation societies have been seeded across the Earth. Many work to preserve knowledge about the sinking and the few physical mementos they can. This becomes more important with time, as the wreck is degraded by its environment and controversial salvage projects struggle to find court approval. Additionally, as of the 100th anniversary of the sinking in 2012, the wreck was protected by UNESCO, increasing pressure to preserve it as it is.

Aficionados share stories and items through themed meetings, but mostly associate through Facebook groups. Kamuda’s Titanic Historical Society claims more than 2,300 members on Facebook. But enthusiasts don’t settle for shared digital space. What is most desired is a closer connection to those who went down with the ship and to the ship itself.

According to the BBC, a Texas collector spent approximately £78,000 to own a key to the ship’s chartroom; a 2016 New York Times article notes that a Halifax graveyard holding 121 bodies recovered from Titanic receives approximately 160,000 visitors annually and closed access to tour buses because so many rolled onto its grounds; and the CBC reported that Canada’s largest private collection contains 1,000 Titanic items. This includes, according to owner Rene Bergeron, a dozen Styrofoam cups brought to the wreck by divers to demonstrate water pressure, suitably crushed by it, and now worth up to $150 each — even though they weren’t even originally on the ship!

Sifting through a collection of more than 120 Titanic-related items in her family’s New Jersey home — chunks of rusted metal, shards of coal, and a crushed Styrofoam cup — Christie Seyglinski gently touched pamphlets and reprinted Senate records. “I have a combination of both floating debris and debris that was actually at the bottom of the ocean,” she said with proprietary pride.

In her 20s, she’s among the younger enthusiasts. Like Kamuda, she was hooked by a movie: At 4 she saw James Cameron’s Titanic, and it’s been a love affair with the ship ever since.

She’s privileged because she met the last living survivor, Millvina Dean — only a newborn during the sinking — before Dean died in 2009. Seyglinski keeps framed letters from Dean and a sketch of the ship’s grand staircase which Dean signed. Several enthusiasts have a specific name on the passenger and crew list for whom they feel special fondness. But only a few actually knew passengers.

When the 100th anniversary came, Seyglinski took a cruise to the wreck site at 41°43’57” N, 49°56’49” W — coordinates dear to her heart. The waters were still and the weather mild as the cruise ship floated more than two miles above the Titanic’s sunken bow. She threw flowers and a letter for those on board the Titanic into the sea.

Six years later, she laughed bashfully and wiped away a tear as she reflected on the memorial service over the wreck from the warmth of her personal collection of memorabilia. “It was probably the most amazing thing I’ve ever done, just being there 100 years to the second,” she said.

Seyglinski keeps a first-edition copy of Filson Young’s book Titanic, published about a month after the disaster, which a friend gave her on the anniversary cruise. Her friend glued a treasured relic from The Big Piece — the section of hull raised from the wreck in 1998 — into its front cover: a patch of horsehair porthole insulation.

Günter Bäbler, cofounder of the Swiss Titanic Society, was present when The Big Piece was salvaged. Biel’s book says he’d been brought along as “the world’s foremost expert on Swiss Titanic passengers.”

Bäbler’s an unusually reserved aficionado — fascinated more by what Titanic tells him about other ships and passengers of the time than the ship itself. An analytical, pragmatic man with prominent eyebrows and a soft smile, he prides himself on neutral and objective scholarship. All the same, he felt an aura of history as he stood on deck, hovering over the Titanic’s remains.

“I had this feeling of being late,” he said. “You’re physically close to something that isn’t there.”

Bäbler was 10 years old when he first heard about Titanic in class. Bäbler remembered asking his teacher why those on board didn’t climb the iceberg. The teacher couldn’t answer. This left Bäbler with a simmering curiosity.

The more serious enthusiasts pride themselves on studying real people, and consider those who simply want to swoon over Leo DiCaprio shivering on a sound stage as, well, gauche.

His local library had only two books on the sinking, but he was pulled along by a desire to fill in the gaps and resolve the contradictions he found. He, like many enthusiasts, considers part of the appeal of the subject the staggering amount to discover. He’s plotted the GPS locations of more than 3,000 Titanic-related sites at TitanicMap.org and sprinkled in coordinates of other sinkings he believes deserve attention. And he’s written a book, Guide to the Crew of the Titanic: The Structure of Working Aboard the Legendary Liner.

Bäbler specializes in collecting papers, relishing details that authenticate them: the stamp of a press ever-so-slightly raised on a passenger list’s back, the distinctive gloss of discontinued photograph papers, the particular color of a company’s authentic ink. But his collection ranges far wider: a 1990s portable steamer for stripping wallpaper, apparently collected simply because of its name, Titanic 2000; salt water — canned in Newfoundland in 1998 — that “may have touched the great ship” (exactly how unique a distinction this is 86 years after the sinking is something the tin does not disclose); even a desiccated orange purportedly brought home in a survivor’s coat pocket and long preserved before finding its way to Bäbler. “I have to laugh about myself a bit, that I have an orange from Titanic,” he said, “and I keep it in a bank safe.”

Like Bäbler, some enthusiasts become authors while others, like self-made Titanic lecturer and professional gardener Will Kindler, give back through artifact curation. “It’s so important that these items be preserved as much as possible, and especially in groups that can be viewed and shared,” he explained in an email. “This history belongs to all of us.”

Kindler, who’s in his 30s, spends most of his free time studying the ship or using 250 search terms to sweep online auctions for items to contribute to public exhibits, especially in spring, when the anniversary of the sinking rolls around. “The fever kicks in every year,” he said, starting in March and burning him out by April 14. Afterward he cools down by focusing on less in-demand maritime disasters. Inevitably, though, he returns to Titanic.

As with so many other things, the Information Age changed the Titanic fan community. In the past, finding another enthusiast involved attending a convention, seeking out addresses of people featured in Kamuda’s journal The Commutator — or meeting by coincidence, as when historians Charles Haas and Jack Eaton, cofounders of the Titanic International Society, collided in the New York Public Library’s card indexes in the 1970s and began a decades-long friendship.

Haas is a burly man in his 70s, with a sonorous voice, immaculate diction, and an upper lip that dips in the center, giving him a falconish look. Though a respected Titanic expert, he stayed a high school teacher until retirement because of the difficulties of transmuting the work into a career. (Bäbler puts a loose guess at only four or five individuals deriving a living from in-depth, original Titanic research.)

In the ’80s, Haas created the Titanic International Society, a pro-salvage group. He prides himself on their officer elections and member surveys meant to stoke fraternity among enthusiasts. “They used to be called affinity groups,” Haas said of cohorts such as Titanic societies, “and you’d develop an affinity not only for the subject matter but for one another.”

Haas worried that groups based mainly online dilute the possibility of forming personal relationships. In contrast, Bäbler — once reliant on the mail to contact enthusiasts — is pleased newcomers today find it easy to locate themselves in a wider group. Many prefer connecting to the community through Facebook because it’s more relaxed and egalitarian.

The downside of Facebook is being overwhelmed by hordes of single-minded James Cameron movie buffs, those who wish for nothing more than to memorialize film characters who were never alive to begin with. The more serious enthusiasts pride themselves on studying real people, and consider those who simply want to swoon over Leo DiCaprio shivering on a sound stage as, well, gauche.

Though united in their interest in a singular event, Titanic historians, fans, and collectors certainly disagree on how to go about their pursuit in good taste and what the boundaries should be. Tour guide Dave Gardner, for example, forgives Titanic-themed inflatable slides, but thinks an internet meme about Titanic victims livestreaming as they drown is mean-spirited. Kindler thinks Titanic-themed inflatable slides are ludicrous, and an Australian billionaire’s long-deferred proposal to reconstruct Titanic is exploitative — though he confesses he’d visit the attraction if it docked locally. Others, such as Bäbler, simply hope tchotchkes such as Titanic-themed bathplugs or ice cube molds are a gateway to more serious interest in the subject.

Every year, as the sinking’s anniversary approaches, enthusiasts prepare for the big day: Haas gathers research for radio and newspaper interviews; Seyglinski stays alert for Titanic gatherings; last year Bäbler reconstructed a passenger list for Carpathia (which was itself sunk in July 1918 after being torpedoed by a German U-boat) while continuing to photograph graves and memorials for TitanicMap.org.

And every April, Dave Gardner guides his earnest and curious tour groups. He takes them to the High Line, an elevated track originally built to unload ships, which is now preserved as a park. Casting his hand out over the city, away from the Hudson, he’ll tell them that the crowd that welcomed survivors on the Carpathia stretched several city blocks back from the river. And then, turning to the piers, he’ll point to where Titanic was to dock (now transformed into a golf driving range).

His tours hit their zenith on the disaster’s anniversary, April 15: “That’s Christmas,” he says, “and I’m Santa Claus.”

Emlyn Cameron is a politics- and history-focused journalist in Brooklyn, New York. Growing up, he was fascinated by the Titanic and celebrated the centenary at his family’s home in California. He graduated from Columbia University’s journalism school in 2019.

This is an excerpt of an article from the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Library of Congress

Why You Should Get to Know the Folks Next Door

My book In the Neighborhood, published 10 years ago this spring, asked how Americans live as neighbors — and what we lose when the people next door are strangers. These questions are just as timely today. Not only is the country dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, it is also facing a political crisis. And on top of these global and national issues, there are often painful personal matters, such as the sort of health crisis that my own family recently experienced. In each instance, neighborhoods have a critical role to play in easing adversity and averting disaster.

The inspiration to write my book came from the murder-suicide of a couple — both physicians — who lived on my suburban street in Rochester, New York. One evening the husband came home and shot and killed his wife, and then himself; their children, a boy, 11, and a girl, 12, ran screaming into the night.

What struck me — besides the tragedy — was how little it seemed to affect the neighbors. A family who had lived on our street for seven years had vanished, and yet the impact on the neighborhood seemed slight. No one, I learned, had known the family well. Few of my neighbors, I later learned, knew each other more than casually; many didn’t know even the names of those a door or two away.

Interestingly, many of the happy connections between neighbors occurred in response to natural disasters.

Do I live in a neighborhood, I asked myself, or just in a house on a street surrounded by people whose lives are entirely separate? Why, I wondered, in this age of instant and universal communication — when we can create community anywhere — do we often not know the people who live next door?

To see if I could connect with my neighbors beyond a superficial level, I asked them if I could sleep over at their houses and write about their lives on our street from inside their own homes. Somewhat to my surprise, about half the neighbors I approached said yes.

Getting to know my neighbors in this way enlivened the experience of living there. It helped me forge connections that enriched my life and made it easier for the people on my street to look out for each other.

After I told my story in the book, I heard from people all over the world about how much they missed close neighborhood ties. They also told of more recent times when they’d managed to connect with their neighbors, and how gratifying those experiences had been.

Interestingly, many of the happy connections between neighbors occurred in response to natural disasters. On the West Coast, readers recounted earthquakes and fires; in the South, hurricanes and floods; in the North, massive snowstorms. “When the power went out,” a Florida man wrote me of his neighborhood during Hurricane Andrew, “we began to cook our meals in the street. We enjoyed getting to know each other and learning each other’s stories. After a few days the power came back and we all went back inside. It’s funny, but I find myself looking forward to the next hurricane so we can catch up.”

Today, we’re all living through an unfamiliar kind of natural disaster — the coronavirus pandemic — and I see that neighbors are connecting once again. We’ve read and heard a lot of these stories, so I’ll share just one from my own family.

Just after New Year’s 2020, my 4-year-old granddaughter, my daughter’s child, was diagnosed with a rare form of childhood cancer. Suddenly, her life and the lives of her parents and 2-year-old sister were upended. What had been the happy, busy life of a growing family was now beset by fear, anger, uncertainty, trips at all hours to the hospital, increased medical bills, and two parents trying to work remotely from home.

We’re 11 times more likely to report high levels of confidence in our neighbors than in the federal government, and 5 times more than in our city councils.

My daughter’s family lives in a suburb of Washington, D.C., where the response to their 4-year-old’s health crisis was … nothing. This was not because the neighbors were unkind; it was mostly because my daughter and her husband, after living in their home for nearly four years, knew few, if any, of their neighbors well.

But the COVID-19 pandemic came just three months after my granddaughter’s diagnosis. Suddenly everyone in the neighborhood was living with fear and uncertainty, working remotely from home, and struggling with unknowns including reduced income. On a neighborhood listserv, someone offered to buy groceries and other supplies for anyone especially vulnerable to the virus.

My daughter responded:

Hi neighbors—

Some of you have offered so generously to pick up groceries for those of us who are immunosuppressed. I’m pregnant and one of my children has cancer. If anyone happens to be at a store this week selling toilet paper, tissues, or paper towels, please pick up some extra for us! Happy to pay, of course.

Thank you!

Valerie

The response was swift and strong:

My daughter will deliver items shortly (I’ll wear gloves when I put the items in the bag, so nothing will have been touched by anyone in the house).

Amy

We dropped off some tissue boxes a few mins ago.

Allison & Michael

I have a couple smaller boxes of tissues I’d be happy to drop off to you. Oh and I can give you a container of Clorox wipes too.

Betsy

I just dropped off paper towels and tissues at your front door.

Fran

And that was only the beginning. For weeks, my daughter has been finding bags of groceries and paper goods on her doorstep; in most cases, the neighbors decline payment. “Don’t be silly,” one wrote. “There will surely come a time when I need a favor from a neighbor.”

Today, my granddaughter’s treatments continue and her prognosis is good. Her family’s life is still upended, but now at least they are aided and comforted to know they live among people who know and care about them. Once again, it took a terrible event to bring neighbors together.

Can we find ways to connect with each other without a disaster?

As Americans, we have an independent streak; our impulse for freedom and self-reliance often comes more naturally than the desire for community. Social trends also work against connections. Two-career couples mean fewer people are at home or have the leisure time to interact with neighbors. Larger suburban homes — and the lots they sit on — increase physical distance. Ever-increasing hours of screen time leave us less time to socialize. And the persistent fear we call “stranger danger” steers us away from meeting others — even those who live nearby.

I’m afraid it would be naive to think that — in the absence of a new disaster — we will all just reach out to our neighbors because it’s a nice thing to do.

So, let me offer a different incentive.

Pandemic aside, this country is experiencing a crisis: Politically, we have torn ourselves in half. Whichever side you’re on, half the country thinks you’re not only wrong, but insane.

It’s a crisis that poses a threat greater than any hurricane, fire, earthquake, or pandemic. Left unchecked, I fear it can rip us in two and in the process — regardless of which side prevails — destroy the very protections we rely on for our freedom.

What is the answer? History suggests if we want to begin to repair the social fabric, a good place to start is our own neighborhoods.

Like the meetinghouses and common greens of earlier times, neighborhoods long have been the building blocks of a healthy civil society. Today, they are a place that allows us to get to know, regularly and intimately, people who may think differently than we do. With effort, we can come to know our neighbors beyond a superficial level, to know their challenges and the fullness of their lives. Once we do that, it becomes hard to mark them only with political labels.

For example, there’s a couple that lives near me. Over the years, I’ve seen them work long hours to build their own businesses — he in sales and she in consulting. I’ve come to know the two children they adopted, and for whom they’ve made a loving home. I watched as they remodeled a spare room for her mom to live in when she could no longer live alone. So I’m not inclined to dismiss my neighbors — and certainly not to think them evil or insane — merely because they’ve posted a lawn sign supporting a national candidate with whom I disagree.

“In this age of bitter partisanship and social division,” writes Ryan Streeter, resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, “unity and social healing are not only possible but happening every day when we work with and rely on those who are closest to us.”

In the 2019 Survey on Community and Society, Streeter and colleagues found that most Americans get a stronger sense of community from those they’re close to, including neighbors, than from “their ethnicity or political ideology.” Moreover, they found we’re 11 times more likely to report high levels of confidence in our neighbors than in the federal government, and 5 times more than in our city councils. Seventy-three percent of us say our neighbors can be counted on to do the right thing.

So let’s not wait for the next natural or even man-made disaster to reach out to our neighbors. We have a strong enough motive: healing the bitter partisanship that infects our country.

How to get started? I think it’s just one neighbor at a time. You don’t even have to sleep over. All it takes is making a phone call, sending an email, or ringing a bell.

Peter Lovenheim is a journalist and author of six books. His 2011 book, In the Neighborhood: The Search for Community on an American Street, One Sleepover at a Time, won the First Annual Zócalo Public Square Book Prize. He is Washington correspondent for the Rochester Beacon.

Originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Review: Rebuilding Paradise — Movies for the Rest of Us with Bill Newcott

Rebuilding Paradise

⭐ ⭐ ⭐ ⭐

Rating: PG-13

Run Time: 1 hour 35 minutes

Director: Ron Howard

In Theaters July 31, Streaming Soon

An explosion of horrific immediacy launches Ron Howard’s documentary about the aftermath of the 2018 Camp Fire, a wildfire that consumed the town of Paradise, California. Making ingenious use of terrifying phone video footage and anguished audio recordings, Howard recreates the chaotic hours when some 24,000 residents went from dropping their kids at school and getting ready for work to racing for their lives through the very gates of a fiery, smoke-choked hell.

“Are we going to die?” a motorist asks a cop who has just informed her all routes of escape are engulfed. “My house is burning,” a patrolling cop reports as dash-cam footage reveals a ball of fire erupting under a cloud of smoke. “Please, God, help us! The windows are melting!” an unseen driver screams as she rolls uncertainly by the shells of burned-out cars.

And finally, after what seems like an eternity, an escaping family’s camera catches a glimpse of blue sky beyond the cloud of smoke.

“We’re going to make it!” the dad yells triumphantly. From the back seat comes the sound of a little boy crying hysterically.

It’s as powerful a 15 minutes as you’ll ever see open a film; Howard’s domestic answer to Steven Spielberg’s D-Day sequence in Saving Private Ryan — only in this case the cinematographers are ordinary people who had the presence of mind to record for posterity what could have been their final minutes.

Howard’s actual camera crew doesn’t arrive in Paradise until a week or so after the flames have burned themselves out, while the town’s displaced residents are still finding places to stay — sitting shell-shocked on cots in a gymnasium, settling in the basements of distant relatives, camping in tent cities on football fields. Their eyes are empty, their mouths slightly agape in did-this-really-happen disbelief.

But the director isn’t interested in telling a story of hopeless tragedy. With a faith in human resilience that has marked his films from A Beautiful Mind to Apollo 13, Howard seems assured of Paradise’s resurrection even before its resident are. Focusing on a handful of indelible characters, he chronicles their slow realization that even after everything changes, life goes on.

One of them is Steve “Woody” Culleton, himself a story in resurrection, the self-described “former town drunk” who dried out, turned his life around and eventually became mayor. Beloved by his fellow Paradisians, he’s among the first to declare he’ll never leave the town, and even before the ashes have cooled has already drawn up plans to rebuild his home.

We patrol the streets of Paradise — indeed, to a large degree only the streets remain — with local cop Matt Gates, an incredibly cool guy who should be played in the narrative version of this film by Deadpool’s Ryan Reynolds. It is he who witnessed his home collapse in flames while on patrol, but he wonders aloud, “I don’t know if it’s worse to have lost your house or be one of the few whose homes came through it.” In one of the film’s few lighter moments, he gestures to an empty lot he’s passing. “It’s cliché, I know,” he says. “But that used to be the donut shop.”

Another is Superintendent of Schools Michelle John, who despite the fact that some of the town’s school buildings are now smoking rubble, determines Paradise will retain its educational identity, setting up makeshift classrooms in houses, barns, and shopping malls. We meet her devoted husband Phil, who surrenders hereto the endless hours of duty while gently reminding her to eat and sleep. “You’re no good to anyone if you’re sick,” he cautions her as they sit in the living room of a distant cousin who has taken them in. As if to prove to the scorched landscape that Paradise will not be bowed, John vows to hold the high school graduation on the football field — intact after the fire but surrounded by towering dead trees that first need to be brought down (and which FEMA, helpful but a tangle of red tape, resists accomplishing on time).

The story of Paradise’s rebuilding is not a litany of improbable success stories. Many people leave town forever, unable to face the memories of that awful morning. At the moment of her greatest triumph — the football field graduation she dreamed of — John is struck with unspeakable personal tragedy. And even good-natured Officer Gates discovers the personal price a community-wide calamity can inflict when you’re not looking.

But this is a Ron Howard film, and in Paradise he has found the real-life crystallization of what he has proclaimed throughout a life on film: In the end, the human spirit will always rise, quite literally, from the ashes.

Featured image: A home burns as the Camp Fire rages through Paradise, CA on Thursday, Nov. 8, 2018 (Photo by Noah Berger) (provided by Bill Newcott)

Mount St. Helens: The Day the Earth Caught Fire

The predawn forest is dark and cold, and quiet except for the crunch of our footsteps over pine needles. Clouds of my breath reflect the light from my headlamp. Gradually, as we reach the edge of the tree line, a sharp, boulder-strewn shoulder appears, forming a diagonal through low clouds.

We’re climbing in earnest now, pulling ourselves over a maze of rocks stretching 4,500 vertical feet. The alternative — trudging up the adjacent crevasse-cracked snowfields, which fall thousands of feet toward the ground at a nearly 45-degree angle — seems horrifyingly exposed. As we inch skyward, the rising sun warms the earth and the vast, black landscape we’re crawling over.

My friend Kelsey and I had peeled ourselves from our sleeping bags in the small hours, fueled up on instant coffee and protein bars, and aimed our headlamps toward the summit of North America’s most notorious volcano, Mount St. Helens. Our 10-mile climb up the southern slope and back to our camp will take us nearly 10 hours.

“The lesson we’re taking from Mount St. Helens is that we need to be working on other volcanoes … so when they wake up, we won’t be nearly as behind the eight ball as those folks were back in 1980.”

Though physically demanding, climbing Mount St. Helens requires no advanced mountaineering equipment or knowledge, and hardy hikers who have taken adequate safety precautions and secured the necessary permits routinely claim a spot on the summit.

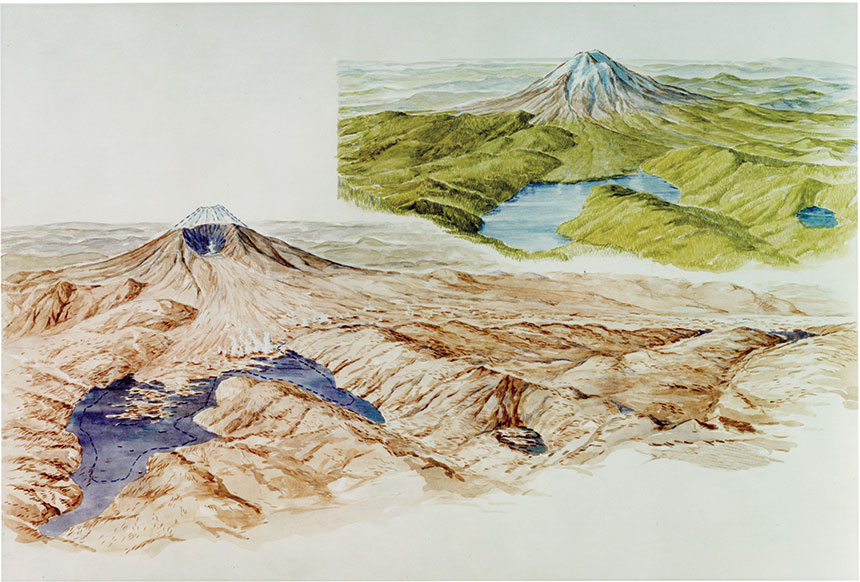

The landscape I’m scaling looked a lot different 40 years ago. In the spring of 1980, rising magma deformed the northern face of Mount St. Helens’ 9,677-foot, symmetrical cone. Things came to a head on the morning of May 18, when the bulging northern slope failed. “The whole top of the mountain slid away in the largest landslide in recorded history, and it filled this valley, as far as 12 miles away, to an average depth of 120 feet,” says Charlie Crisafulli, a U.S. Forest Service research ecologist who began studying Mount St. Helens just after the eruption.

Crisafulli likens that landslide to removing the lid of a pressure cooker; immense pressure had been building inside the mountain, which the landslide released, sending an incredibly powerful blast of lava blocks, snow, ice, and rocks outward at hundreds of miles per hour. “It leveled the trees like they were matchsticks,” Crisafulli says. “Then, beyond the extent of the toppled forest, the heat associated with the blast was enough to sear the needles of the conifer trees, killing them, but not leveling them, so you have a standing dead forest.” The devastation didn’t stop there. “It melted glaciers and ice, creating these slurries of cement-like consistency down the side of a mountain, called mudflows.”

Later came pyroclastic flows — currents of super-heated gas and rock that move at speeds of up to 450 miles per hour — laying waste to anything they touch. And rising from the newly formed crater was that volcanic signature — an 80,000-foot-tall mushroom cloud that scattered visible ash across 11 states.

All told, 57 people died in Washington State’s most infamous natural disaster — the most destructive volcanic eruption in our nation’s recorded history — that also destroyed 47 bridges, 15 miles of railways, 185 miles of roads, and some 250 homes. In the 20th century, it’s preceded only by the 1917 eruption of Lassen Peak in California. Millions of Americans alive today may remember opening their newspapers to read about Mount St. Helens’ eruption or learning about it on the evening news. Some may even recall brushing ash off their car windshields.

As an ecologist, Crisafulli’s job is to observe the widespread environmental changes taking place post-eruption. Closer to ground zero, scientists are offered a rare opportunity to study environmental renewal from “a clean slate,” as he calls it, where every living thing — from massive, ancient old-growth trees to the plants and animals they sheltered — was destroyed. Mount St. Helens offers an unparalleled opportunity, he says. “Scientists in the U.S. didn’t have experience with explosive volcanoes, so we really didn’t have a lot of understanding of what to anticipate and how to even approach our work necessarily.”

Because Mount St. Helens is so close to large population centers with major research institutes and sits on public — not private — lands, scientists were on the ground very quickly before and after the eruption, as opposed to months or years later when eruptions happen in more remote places. “The opportunity was not squandered. Within the first couple of years, there were over 200 studies established and included thousands of researchers,” Crisafulli says. “They looked at everything from molecules to the entire ecosystem. This highly skilled cadre of scientists entered the scene and collaborated to develop a remarkable long-term dataset. For 40 years, people have been studying the volcano and really trying to understand what were the initial ecological responses. How did the longer-term processes of succession and assembly of biological communities happen.”

Crisafulli and his colleagues have taken their findings to sites of other volcanic eruptions all over the globe. Their findings inform understandings of how ecosystems recover from more than just volcanic activity — they can be applied to environmental renewal after activities like clear-cut logging, mountaintop removal mining, and dam removal. “Lessons from St. Helens have helped inform how succession might occur there and how managers might go about using those lessons to get other ravaged lands back into a productive state.”

Lacking a geologist’s trained eye, I momentarily forget I’m traipsing along the back of the geophysical equivalent of a serial killer. But that fact comes into shocking focus as we ring equipment: a beefy tripod next to a large, metal box that I later learn is a GPS station, installed to measure ground surface movement, or deformation — indications that the mountain could someday wake up again. “That’s there to tell us if the surface of the volcano is changing shape at all,” says Seth Moran, the scientist-in-charge of the USGS Cascades Volcano Observatory, which is tasked with researching, monitoring, and community outreach around the threats posed by the Northwest’s most famous volcano. The agency was created in the months after May 1980 to better prepare for a future eruption in Idaho, Oregon, or Washington.

The station I pass is one of two dozen scattered around Mount St. Helens, each one keeping an eye on deformations created by surging magma within the mountain. It’s all part of an early warning system designed to predict what might happen here and to better alert people living in the shadow of the volcano.

(USGS)

Before Mount St. Helens rumbled to life starting in March 1980, there was very little monitoring of the volcano — in fact, the mountain had just one monitoring station when a series of earthquakes alerted scientists that something was going on that spring. “There was a tremendous scrambling and marshaling of resources, and within a couple of weeks a pretty good-sized network was installed and operational. And that was with some luck,” Moran says, explaining that clear weather allowed good access to the mountain, and “there happened to be some equipment lying around.”

Moran adds, “It was also pretty dangerous, and people that were working on the volcano were taking a lot of risks in doing that. But there was a lot of baseline understanding of the volcano that was missed because there was not anything on the volcano really before then.”

Today’s technology, research funding, and warning procedures represent significant improvements and advancements over what was in place 40 years ago. The findings from 1980 are being applied to volcanic systems around the world, many of which pose greater dangers to surrounding communities than St. Helens ever did. For example, Moran says six volcanoes in the Cascade Range of the American Northwest are inadequately monitored today. He’s pushing for more monitoring on each of them, especially on Oregon’s Mount Hood, which, while possessing less eruptive potential than Mount St. Helens, sits closer to major population centers, posing a potentially more deadly threat. In fact, half of America’s 10 most dangerous volcanoes sit within the Cascade Range.

On Mount Hood, laws governing land use, which protect federal wilderness areas from the building of additional structures, have created regulations that prevent scientists from installing adequate monitoring stations. It’s a battle that pits scientists against environmentalists in an ongoing tug-of-war, with little indication as to how much time we have before an eruption. “The lesson we’re taking from Mount St. Helens is that we need to be working on other volcanoes to get them at least to a basic level so when they wake up, we won’t be nearly as behind the eight ball as those folks were back in 1980,” Moran says.

Our climb finally takes us beyond the boulder field, and soon we’re staring straight up toward the summit, where small puffs of steam catch a cool breeze. Improbably, in this alpine desert of barren rock, a hummingbird zips past overhead, making its way up the mountain. In the distance, the clouds cradle a view of Mount Hood’s pyramid to the south and Mount Adams to the east, two more Northwest members of the Pacific Ring of Fire, a necklace of active volcanoes arching from New Zealand to Japan to Washington State to South America.

The last 1,000 feet of the climb is an exercise in patience as we walk on ash the consistency of kitty litter. Every tedious step up is offset by a slight sinking back down, and I find I make better progress if I trudge upward without stopping for a break. I keep my eyes trained on the summit ridge.

After a final push, we’re standing at the 8,300-foot summit — no longer a smooth cone, but a jagged, semicircular rift hugged by a cornice of dirty snow. Steam, created when melting snow seeps through cracks in the rock and meets hot magma, plumes from multiple spots inside the crater. The earth here, with the planet’s great tectonic forces exposed, feels very much alive — and unsettled, a reminder that earth is governed by fire, and land is born of violence. It’s no surprise this rowdy hunk of geology earned the name Loowitlatkla, or “Lady of Fire,” from the Puyallup tribes and Lavelatla, “smoking mountain,” from the Cowlitz tribes.

Steam, created when melting snow seeps through cracks in the rock and meets hot magma, plumes from multiple spots inside the crater.

Careful not to get too close to the brittle edge, I peer into the crater incised by the 1980 blast. Within this breach sits a chaotic scene of rock and ice falls, steam, rivers of snowmelt, and hot springs. At the crater’s center sits a new dome, signaling the mountain’s regrowth as magma continues forcing its way into the mountain’s core. A newborn glacier — Crater Glacier — hides behind the south side of the dome.

This chunk of ice is significant for a few reasons: It sits at a relatively low elevation, and it’s the youngest on the continent. And in a time when climate change means most talks of glaciers are accompanied by the word receding, Crater Glacier is actually growing.

Looking north, the horseshoe-shaped crater opens toward a vast fan of scarred earth, called the Pumice Plain, with the blue waters of Spirit Lake standing out against the brown, bombed-out landscape. Scores of massive logs, once part of a magnificent old-growth forest, hug one shoreline — another reminder of the volcano’s power. Mount Rainier, the state’s tallest peak and the most glaciated mountain in the Lower 48, rises above the rumpled landscape.

It’s hard to imagine that St. Helens once bore a cone even more symmetrical than Rainier’s, and was similarly draped in massive glaciers. Rainier, too, is an active volcano, one more in a chain running from southern British Columbia to Northern California. Another sleeping giant, hovering over the Pacific Northwest, waiting its turn to unleash the most powerful natural forces on the planet.

Megan Hill contributes to AFAR, Sierra, Hemispheres, Global Traveler, among other publications. She wrote “How a Dying River Was Brought Roaring Back to Life” (March/April) about dam removal on the Elwha River in the Pacific Northwest.

This article is featured in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Science History Images/Alamy Stock Photo