What You Need to Know About Coronavirus

“Your Health Checkup” is our online column by Dr. Douglas Zipes, an internationally acclaimed cardiologist, professor, author, inventor, and authority on pacing and electrophysiology. Dr. Zipes is also a contributor to The Saturday Evening Post print magazine. Subscribe to receive thoughtful articles, new fiction, health and wellness advice, and gems from our archive.

Order Dr. Zipes’ new book, Bear’s Promise, and check out his website www.dougzipes.us.

Unless you have been living on another planet these past few weeks, you have been deluged with daily updates about the new coronavirus, 2019-nCoV, the seventh member of the family of coronaviruses that infect humans. The information, depending on its source, is at times reassuring and at other times frightening. At the very least, it is unsettling, especially as we read about the impact the virus has had in China, particularly in Wuhan where it began, perhaps transmitted by camels, bats or the pangolin, an animal used in traditional Chinese medicine. Infection has spread to over twenty countries, mostly in Japan, Singapore, Thailand, Hong Kong, and other Asian countries.

The purpose of this column is to provide readers with some facts as we know them today, and to offer reliable sources where readers can obtain valid information, such as from the Johns Hopkins website, the World Health Organization, or the American Medical Association that deliver expert information about the impact and extent of nCoV.

As I have written previously, due to deficiencies in worldwide health care, unfounded distrust of vaccinations and health services, and poor health infrastructure, our planet is ill- prepared to handle a pandemic of coronavirus proportion. At the time of this writing, there are around 40,000 confirmed cases of 2019-nCoV infection — the vast majority concentrated in China — and more than 900 deaths, for about a 2 percent mortality. One of the deaths included the unfortunate Chinese physician who first called attention to the new virus. Twelve cases of nCoV infection have occurred in the U.S. (nine people had been in Wuhan) with no deaths to date, although a 53-year-old American man has recently died in China. Thousands of people have been trapped on three cruise liners in Asia due to fears of contagion. Human-to-human transmission has been documented, leading the World Health Organization to declare a public health emergency on January 30, with a similar declaration by the U.S. a day later.

Coronavirus outbreaks are nothing new. The Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) virus was another coronavirus originating in China in 2003, not as contagious as nCoV, though more lethal. SARS infected over 8,000 people, killing almost 10 percent of infected people before it was contained. The Middle East Respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS) was also a coronavirus stemming from animal reservoirs such as bats, perhaps with intermediate hosts. MERS infected 2,494 people and caused 858 deaths (34 percent mortality rate), the majority in Saudi Arabia.

In comparison, the influenza virus kills less than one person per thousand infected (0.1 percent), but about 200,000 people are hospitalized with the virus each year in the U.S., leading to about 35,000 deaths.

The SARS pandemic cost the global economy an estimated $30 billion to $100 billion. The full economic impact of nCoV is yet to be felt, and while the Chinese economy is likely most affected, the impact will be worldwide as it upends manufacturing, shipping, travel, education, and other activities.

Such respiratory viruses travel through the air in tiny droplets produced when an infected person breathes, talks, coughs or sneezes. This coronavirus is moderately contagious, harder to transmit than measles, chickenpox, and tuberculosis, but easier than H.I.V. or hepatitis, which are spread only through direct contact with bodily fluids. Face masks may help prevent its spread, though that has yet to be established.

The incubation period after being infected before symptoms manifest appears to be 2-14 days (more likely 5-6 days), raising the possibility of transmission before a person knows they are infected, though transmission by symptomatic persons is more probable due to a greater viral load at that time. Older men with other health issues seem more likely to become infected and young children less likely.

Symptoms can include fever, cough, shortness of breath, muscle ache, confusion and headache, sore throat, and GI problems such as diarrhea, nausea, and vomiting. Pneumonia has been documented in the majority of hospitalized patients and when severe, is probably the cause of most deaths. The median time from first symptoms to becoming short of breath is five days; to hospitalization, seven days; and to severe breathing trouble, eight days.

Additional information about 2019-nCoV is needed to better understand transmission, disease severity, and risk to the general population. Public health measures to quarantine infected individuals and prevent spread have been instituted worldwide.

Management of people with 2019-nCoV is largely supportive, although antiviral medications have been used, as have antibiotics in patients with superimposed bacterial infections. The effectiveness of antiviral medications is unproven, although they may have been effective in treating SARS. Interventions that will ultimately control nCoV are unclear because there is currently no vaccine available and one is not likely for a year or longer.

Staying home when ill, handwashing, and respiratory care including covering the mouth and nose during sneezing and coughing, were effective in controlling SARS and should be advocated for treating nCoV as well.

Presently, there is no reason for panic in Western countries. We need to follow updates and hope containment will eliminate the threat of this new nCoV pandemic over the next month or so. Remember that the virus is transmitted by humans during sneezing or coughing. Avoid such individuals or wear a face mask if in contact. The CDC does not recommend widespread use of masks for the healthy, general public at present.

If you sneeze or cough, do so into a disposable cloth or paper. A fist bump greeting rather than a handshake might be wise. For viral particles that have settled on the floor, table, and other objects, hand contact then brought to your face can transmit the infection. So, wash! wash! wash! your hands with antibacterial soap after contacting such surfaces and before touching your face. Alternatively, use an alcohol-based hand sanitizer containing at least 60 percent alcohol. Green leafy vegetables and other sources of vitamin C can help the immune system fight off disease.

If we all pay attention to these simple measures, we will help contain the virus and it will eventually die out, particularly as warmer weather approaches.

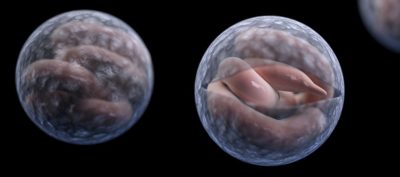

Featured image: Shutterstock

Is the Water You’re Swimming in Safe?

There are few summer pastimes that compare to the bliss of a cannonball into a cool lake. But if you think the dangers of swimming are limited to drowning, you’re ignoring the sometimes invisible hazards that can lurk in the depths.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently issued reports on disease outbreaks in both treated and untreated bodies of water from 2000-2014. Although Americans swim hundreds of millions of times each year without incident, we also see dozens of self-reported outbreaks caused by bacteria, viruses, and parasites, and warming waters — over time — can bring about new risks. Taking precautions before taking a dip can prevent the spread of disease for everyone.

The parasite Cryptosporidium is a leading cause of waterborne illness in the U.S. It accounts for 79 percent of cases of illnesses in the CDC’s report of chlorinated waters. The danger of this bug is that it is encased by a hard outer shell that allows it to survive in chlorine-treated pools for up to 10 days. The best practice is to keep it out of the water in the first place, according to Michele Hlavsa, an epidemiologist and Chief of the CDC’s Healthy Swimming Program. That means refraining from swimming if you or your child have recently had diarrhea. The report shows the most frequent settings for outbreaks are hotels, possibly because pool maintenance is undertaken by staff with many other responsibilities, Hlavsa says. You can check with pool staff to find out their inspection score from the CDC. Hlavsa recommends buying test strips to measure chlorine and pH levels as an added pool precaution.

Untreated waters, like lakes, rivers, and beaches, present a much wider variety of risks. Water that is crystal clear isn’t necessarily safe for swimming, Hlavsa says. Norovirus, E. coli, and Shigella outbreaks peak in July. A growing risk is the presence of harmful algal blooms: “In recent years, harmful algal blooms have been observed with increasing frequency and in more locations in the United States, possibly because of increasing nutrient pollution and warming water or improved surveillance.” Evidence suggests that harmful algal blooms are happening more often and for longer periods of time in a variety of American waters due to field runoff and climate change. Hlavsa recommends steering clear of discolored, smelly, foamy, or scummy water and obeying all posted advisories when using untreated recreational waters. She also says to avoid swimming wherever discharge pipes can be found and after a heavy rainfall that can contaminate waters.

The most terrifying parasite in the water is also among the rarest: Naegleria fowleri. Known as the “brain-eating amoeba” that enters through the nose in warm freshwater, Naegleria fowleri kills individuals within two weeks of infection. Each year brings only 0-8 cases of the parasite, but Hlavsa says the locations of recent cases have been alarming: “It used to be found only in southern states, but recently we’ve seen cases in Virginia, where we haven’t seen it for decades, and Minnesota and Indiana, where we’ve never seen it before.” The reasons for the amoeba’s northward migration aren’t clear. In fact, little is known about why some become infected and others do not, since cases are so rare. Since the amoeba can only enter the body through the nose, wearing nose clips is a good precaution against this killer bug.

The statistics in the CDC’s reports are at the low end of realistic numbers for recreational water disease outbreaks. Because of differing capacities around the country to properly identify and report illness, exact numbers would be impossible to obtain. The tendency for swimmers to be travelling during their use of recreational waters also makes it difficult to pin down an outbreak to its source.

Like anything else, swimming has its risks, but that doesn’t mean you should completely eschew the water. Only ten deaths from disease outbreaks in recreational waters were reported from 2000-2014. When compared with the more than 100 fatalities from fireworks in the same time span, the perils of taking a plunge might not seem so bad.