Fannie Lou Hamer’s War on Voter Suppression

Lyndon B. Johnson was distressed a few days before the start of the 1964 Democratic National Convention. In a presentation to the party’s Credentials Committee in an Atlantic City hotel ballroom, a Black Mississippi woman named Fannie Lou Hamer was giving a disturbing account of her various past attempts to exercise her right to vote. She was “sick and tired of being sick and tired.”

Hamer, then 46 years old, had been the youngest of 20 children in her family, leaving school in sixth grade to work on Mississippi plantations. She had been poor her entire life, and suffered from polio as a young girl. Just three years earlier, she had been sterilized against her will while hospitalized for a minor surgery. But her address to the 108 committee members that day recounted, in sickening detail, numerous instances of violent institutional repression that had prohibited Hamer from participating in her country’s — and the Democratic Party’s — democratic process.

She first failed the arcane and discriminatory literacy test that was administered to African Americans in 1962. Then, she was on a busload of hopeful Black voters that was pulled over for being the wrong color (too yellow). Then, the plantation owner kicked her off the land she sharecropped (for attempting to register to vote). Then, in 1963, she was arrested with several others after attending a voter registration workshop. While in jail, she was brutally beaten with a blackjack by other prisoners at the orders of a state trooper who told them to, according to this magazine, “Make the bitch wish she was dead.”

At the Democratic Convention, Hamer was speaking on behalf of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a grassroots political project that aimed to replace the state’s elected delegation on the premise that it was illegally selected with a segregated vote — a “white primary.” Less than seven percent of eligible Black adults were registered to vote in Mississippi in 1964. With the cooperation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC or “Snick”), NAACP, Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and the Congress of Racial Equality, activists in the South organized tens of thousands of mostly Black, poor and working-class people in a precinct-level effort to subvert the all-white Democratic stronghold in the state.

President Johnson worried that the MFDP — and a potential interracial delegation — would alienate the South’s white Democratic voters, sending them into the arms of the Republicans. During Hamer’s speech, he called an impromptu press conference, leading many to think he was about to announce his running mate. Instead, he gave a commemoration of President Kennedy, who had been assassinated nine months earlier. The television networks still played Hamer’s speech, though, during their primetime broadcasts. Their viewers saw the poor Black sharecropper’s impassioned indictment of her country: “Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?”

Hamer’s testimony was an uncomfortable dose of reality for liberal America. Even today, her story teaches largely unexamined lessons regarding the background work of the civil rights movement and its many proponents. As scholar Maegan Parker Brooks wrote in her recent biography of Hamer, “The life story of a disabled, impoverished, middle-aged black woman from the rural Mississippi Delta challenges widespread perceptions of who participated in — as well as how they influenced — mid-twentieth century movements for social, political, and economic change.” Hamer is not a household name like Martin Luther King, Jr. or John Lewis, but her role in this transformational period of American history shows us what was at stake, and indeed still is.

Hamer didn’t appear at the 1964 Democratic National Convention out of thin air. Along with three other Black candidates in the state, she ran a primary campaign against the longtime Mississippi representative Jamie Whitten. The Freedom Democrats had been working since the previous fall to both register Black Mississippians and hold straw votes in their own “freedom-registration books” to show what electoral participation could look like in the state where African Americans made up 42 percent of the population. That summer, a profile of Hamer in The Nation posited that “The wide range of Negro participation will show that the problem in Mississippi is not Negro apathy, but discrimination and fear of physical and economic reprisals for attempting to register.”

During the Freedom Summer of 1964, the civil rights groups that made up the Council of Federated Organizations undertook a statewide organizing effort to account for Black non-voters and register as many as possible. They also established Freedom Schools, community centers, and a Freedom Labor Union. At the heart of this undertaking was the oversized contribution of SNCC, the activist group Hamer had worked with diligently since attending a mass meeting in 1962. Hamer traveled around the state, stirring Black audiences with speeches that motivated them to act for their own liberation. (“It’s a shame before God that people will let hate not only destroy us, but it will destroy them. Because a house divided against itself cannot stand and today America is divided against itself because they don’t want us to have even the ballot here in Mississippi.”) At the same time, SNCC’s army of volunteers — largely white college students from the North — were moving around Mississippi organizing for participatory democracy at every level.

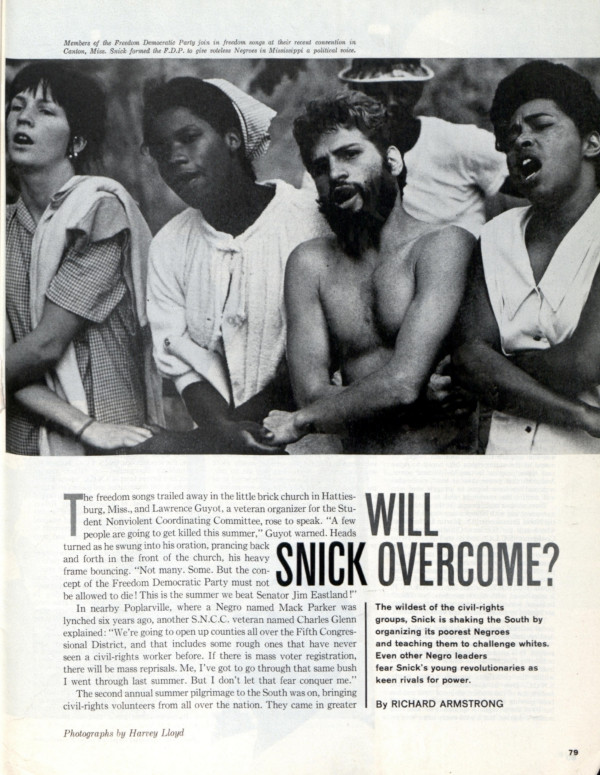

In 1965, this magazine covered the student group (“Will Snick Overcome?”), pointing out the markedly more radical approach SNCC employed compared to a group like the NAACP. Arising from the sit-ins of 1960, SNCC was an early opponent of the Vietnam War and decidedly non-hierarchical. While it claimed manpower from the country’s college students, SNCC aimed to cultivate leadership at the community level in its campaigns. The Post recognized this unique tactic of SNCC’s “shock troops,” even if it seemed tedious: “The whole concept of building a political force out of tenant farmers, slum-dwellers and the unemployed is a radical departure from American political norms.”

In response to claims that communists and Marxists — perhaps even foreign ones — were stirring up all of the trouble in the South, Hamer gave a simple response in a speech at a mass meeting in 1964: “People will go different places and say, ‘The Negroes, until the outside agitators came in, was satisfied.’ But I’ve been dissatisfied ever since I was six years old.” Hamer’s lifelong dissatisfaction steered her toward a fight for voter enfranchisement, and later, as Brooks puts it in her biography, fights “against white supremacy, police brutality, sexual assault, segregated education, food insecurity, and health care access” among others.

In June, before the convention, three Freedom Summer organizers — James Earl Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman — were murdered near Philadelphia, Mississippi. The Ku Klux Klan had grown its numbers in the area and burned down 20 black churches that summer, many of which were hubs for civil rights activity. The three men had been involved with a church that housed a Freedom School, and several Klansmen, policemen, and a minister conspired to shoot them and hide their bodies. The case was a national outrage, but over the course of the federal investigation eight bodies of Black men were found, several of them civil rights workers as well.

After Hamer made the MFDP’s case to the Credentials Committee at the convention, the Johnson administration countered with a negotiation offer: the MFDP could have two at-large seats (picked by Johnson) without unseating any of the Mississippi delegation, and the party would ban segregated delegations in 1968. Hamer and other Freedom delegates were fuming at the prospect of accepting such a paltry deal, but leaders from the NAACP and SCLC, including Martin Luther King, Jr., advised them to take it. The MFDP unanimously voted against accepting the offer, in an outright rejection of the legitimacy of the Mississippi delegation.

That repudiation is an important aspect of Hamer’s legacy in that it refuses to conform to what author Jeanne Theoharis calls the “national fable” of the civil rights movement: the idea that this era of our history can be represented as a settled legislative triumph featuring a small cast of iconic heroes instead of as a disruptive, radical mass movement against institutional white supremacy. Hamer was not interested in a reassuring narrative for white folks; she wanted liberation.

The next month, Harry Belafonte took a group from the MFDP — including John Lewis and Fannie Lou Hamer — on a trip to Guinea. They were received with a warm welcome, meeting President Ahmed Sékou Touré and touring his palace. On the trip, Hamer wrote in her autobiography, she felt she was treated much better in Africa than in America, and she noticed many of the negative stereotypes she had been led to believe about Africans were incorrect. “So when they say, ‘Go back to Africa,’” she wrote, “I say, ‘When you send the Polish back to Poland, the Italians back to Italy, the Irish back to Ireland and you get on that Mayflower from whence you came and give the Indians their land back.’ It’s our right to stay here and we stay and fight for what belongs to us.”

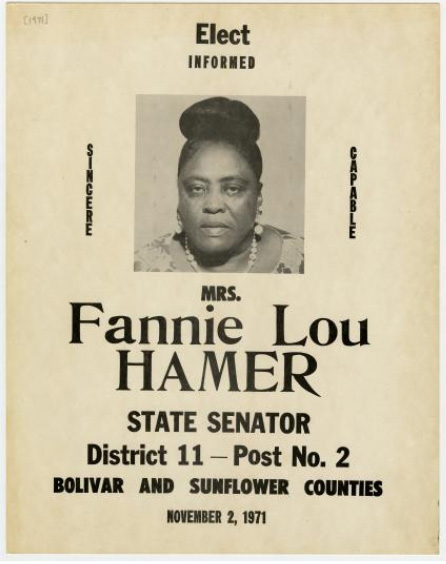

Featured Image Courtesy of the Archives and Records Services Division, Mississippi Department of Archives and History