The Cover Girl on the Titanic

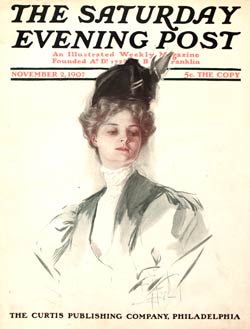

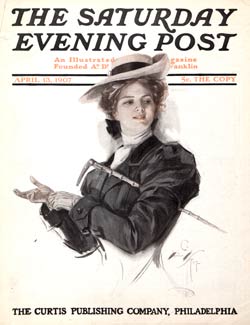

Hundreds of women were featured on the cover of the Post in the early decades of the last century. Young, beautiful, dressed at the height of fashion, they were captured by painters like J. C. Leyedecker, Guernsey Moore, and Sarah Stillwell Weber.

Today the names of these cover girls are, for the most part, lost to us. One rare exception is the women seen on the April 8, 1911 cover: Dorothy Gibson.

We know her name because she was a favorite subject of Harrison Fisher. And we know her because of a fateful decision she made one year after this magazine cover appeared, when she chose to sail on the RMS Titanic.

Dorothy Gibson, born in Hoboken in 1889, was living with her mother in New York in 1910 when she began to earn a living singing and dancing. Soon she was offered work as a model. After Harrison Fisher began painting her, Ms. Gibson became one of the iconic beauties of her time, rivaled only by the women drawn by Charles Dana Gibson (no relation).

It wasn’t long before she was approached by some New York film studios. She proved so successful that she was offered a generous contract by the Éclair Company. She starred in several dramas and comedies, including A Lucky Holdup, which premiered the same week she and her mother, returning from a European trip, boarded the RMS Titanic in Cherbourg.

She was walking on deck after an evening of card playing when she felt the deck lurch slightly. Seeing from the ship’s officers that something was wrong, she didn’t return to her cabin but headed straight for a lifeboat.

She was in the first lifeboat lowered to the water, one of just 19 people in a boat designed to hold 65. Another passenger in her life boat recalled, “the sea was perfectly calm—not even a ripple on the surface… suddenly all the lights dipped simultaneously to a pale glow. A moment or two later [we] saw, silhouetted against the star-lit sky, the stern of the ship rise perpendicularly into the air… Then, with a prolonged rush and a roar like ten thousand tons of coal sliding down a metal chute several hundred feet long, the great ship went down… A great cry arose on the air from the surface of the calm sea where the ship had been.”

Ms. Gibson recalled that sound: “I will never forget the terrible cry that rang out from people who were thrown into the sea and others who were afraid for their loved ones.”

Rescued by the Carpathia, she arrived in New York on April 18. Almost immediately she had agreed to a suggestion from the studio’s producer to make a movie of her experiences. Within a week, she was filming Saved from The Titanic, wearing the same evening gown, long sweater, and gloves she’d worn the night she escaped the sinking ship. The ten-minute ‘feature’ movie proved highly successful, but Ms. Gibson soon lost interest in the movies.

She was considering a career in opera when, in 1915, the producer of Éclair Studios was involved in an automobile accident that killed a man. During the subsequent inquiry, the court—and then the public—learned it was Dorothy Gibson, not the producer, who had been driving the car. Worse, she had been having an adulterous affair with the producer for several years.

In the wake of the scandal, the producer divorced his wife and married Gibson but they, too, were divorced just two years later.

Ms. Gibson, still with her mother in tow, lived on her movie residuals and alimony and eventually decided to move to Europe in 1927 where the cost of living was much less. She and her mother lived in France and Italy, ultimately settling in Paris. She was still there when World War II began.

We are unsure of what happened to her over the next few years; her account is vague and sometimes contradictory. Until America entered the war, she had been allowed to visit her mother in Italy. But in 1941, she was suddenly unable to return to her Paris home. At some point, she was arrested, then sent to San Vittore prison in Milan.

She surfaced again in 1944 when she tried to enter Switzerland. She told the American consul in Zurich she had escaped with the help of an Italian official. He had obtained her release by falsely informing Nazi officials in Italy that Ms. Gibson would enter Switzerland to spy for the fascists.

Apparently the allied authorities never determined whether she was pretending to be a spy or was, in fact, a spy for the German occupiers of Italy. She returned to Paris in 1945 and died there in 1946.

She was outlived by her mother, who survived her by 15 years. As Dorothy’s mother grew even more feeble, she grew vocal in her criticism of the allies. She often made antisemitic, pro-Nazi statements, which led some to infer that her daughter, Dorothy, had been a fascist sympathizer. As in so much of her later life, her political sympathies have never been determined.