North Country Girl: Chapter 28 — The Age of Aquarius Comes to Duluth

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

I didn’t tell Doug Figge about Wendi Carlson’s advice, that the key to enjoying sex is more sex. I didn’t have to. His mind was on the same track, the only track 17-year old boys’ run on, the track with the thundering locomotive of sex hurtling along, blowing all other thoughts away.

The day after the first man landed on the moon and I gave up my virginity, Doug called with the woeful news that Joe Sloan had emerged from his basement with powder burns and a singed shirt, accompanied by a powerful stink of cordite. His parents decreed that their house, including those forgotten bedrooms, was off limits.

Doug knew it was one of my mother’s class days. “Please, please,” he begged. “Let me come over. It will be okay, we’ll be quick,” he said as if that were a selling point. “Fine,” I sighed.

One of the things I learned from my first experience was that sex was messy, and should not take place on my mother’s ivory brocade French Provincial couch. Doug pulled into my driveway, I let him in the backdoor, and hurriedly escorted up him to my bedroom.

It was the middle of the afternoon and the sun streamed through my windows. I was shy about taking off my clothes in the summer glare, and not especially looking forward to seeing my fairly unattractive boyfriend naked either. I turned my back, stripped and slipped between the sheets, and there was Doug, nude and on top of me and ready.

I thought we were safe. My mother usually wasn’t home till three. But some vagary of the University of Minnesota’s college calendar or maybe the excitement of the moon landing had caused my mother’s class to be canceled that day. I heard a familiar car pull up to the house and thought “This is bad this is bad this is bad,” and tried to shove Doug off me. His eyes were squeezed shut, beads of sweat popping out on his wispy moustache; he was oblivious. “Doug Doug Doug,” I whispered hoarsely, as I heard the house door open and not only my mother’s voice, but my sisters’ as well. I pushed him harder and finally got him off me and he realized that my mother was home.

As Doug’s Corvair was in the driveway, my mother knew we were in the house alone, which she had strictly forbidden fearing exactly what had come to pass. Before Doug and I had a chance to find even our underwear, my mother flung open my bedroom door and lost her mind. She didn’t know whom to hit first. She whacked Doug about the head a few times, as he tried to find his jeans, the hell with his briefs, then she turned on me, as wordless as a banshee, unable to articulate what she had seen with her own eyes: her fifteen-year-old daughter having sex. I burst into tears and Doug made his escape.

That event is burned into my memory with almost a physical pain. I can feel the warm air coming in through the windows, pushing the sheer white curtains into the room. I can hear the torrent of my mother’s shrieks, and my entire body burning and blushing and trying to vanish into thin air. Out of the corner of my eye, while trying to duck my mother’s roundhouses, I see a blur that is Doug, holding his shirt and shoes, rushing down the stairs and out of my life.

A sadder but wiser fairy had come to undo one of my wishes, a wish that had gone horribly wrong. I no longer had a boyfriend. My mother forbade me to see Doug Figge ever again.

When I told Wendi Carlson about that shameful, sordid experience, she burst into peals of laughter, which shocked me into learning an important lesson: if your good friend cracks up at your sad story, it’s not the tragedy you think it is.

Egged on by Wendi, I held my gang of girlfriends spellbound for the remaining weeks of summer with the gripping tale of my mother catching me in bed with Doug Figge. “Tell it again!” they’d squeal, as we sat by a bonfire or dangled our legs in the water off a lakeside dock. I’d get to the point where Doug tore bare butt down the staircase, and they’d roar, squirting beer through their noses. Every time I re-told that tale of horror, it became less real, more like something that happened to another person.

“You need a new boyfriend!” cried Nancy, Wendi, and all the other girls. I wasn’t sure that I did. My romantic history consisted of a single date with Wesley Baggot, being publicly dumped by Steve LaFlamme, a forced make out session with a candidate for a skin graft, and having a boyfriend for six months that I didn’t really like and who never took me out once on a real date.

If I was going to have another boyfriend, I was going to pick him out myself. No more waiting passively for some boy to choose me; I had enough of that during those nightmarish ballroom dance classes. From now on, every day was going to be Sadie Hawkins Day.

I rejected all the efforts my pals made to fix me up. I studied the eligible guys in the packs that hovered around us, looking in vain for potential boyfriend material, someone who was good-looking and smart and funny. My imaginary future boyfriend had to go to East High, so he could hold my hand in the halls and take me to a school dance. I was through with boys who went to weird other schools, unless Joe Sloan reappeared.

Maybe it was this gritty new determination, maybe it was getting rid of my virginity at fifteen-and-a-half: I grew a backbone. I found I could talk, and laugh, and flirt with boys, ignoring the voice in my head that told me I sounded like an idiot.

Now I needed to shed my gawky nerd look, my face hidden behind those oversized tortoise-shell spectacles with the Coke bottle lenses. My mother was still not talking to me, just shooting me looks that alternated between disappointment and disgust. I turned on my father at every occasion, begging for contact lenses. Dad preferred that I remained unattractive; he didn’t know that the worst had already happened. My eye doctor won the argument for me, pointing out to my father that contacts would slow down my eyes’ deterioration to Mr. Magoo-level near-sightedness, and eliminate the need to buy new and thicker glasses every year. I got my contacts and I promptly lost one in our gold shag carpet. So much for my dad saving money on my eye care; it was back to the doctor to order another $30 contact. Now both my parents were mad at me.

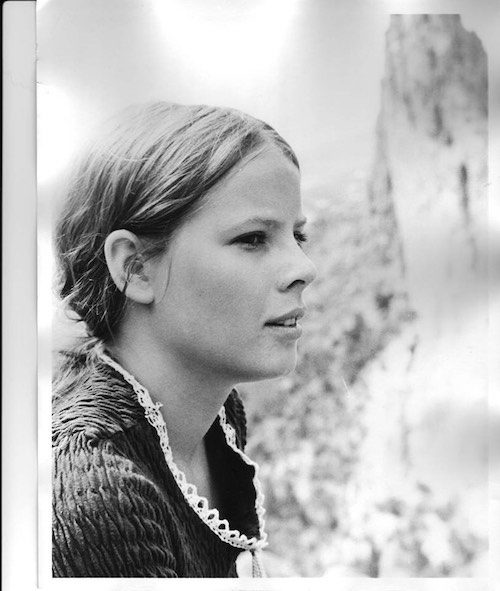

Who cared about parents when there was a potential boyfriend somewhere out there, a boyfriend who could now gaze directly into my green eyes, while stroking my hair. I hadn’t allowed a scissor to come near my head for months and my hair now flowed halfway down my back, an unremarkable brown, but thick and shiny with youth and health, perfect hippie girl hair. I also decided to stop letting my mother pick out my clothes. During our annual shopping trip to Minneapolis I ditched my mom and sisters in Dayton’s Back to School section and found an incense-smoky store where I bought a purple leather fringed jacket, a collection of gauzy Indian shirts, and embroidered bell bottom jeans. Suddenly instead of a four-eyed geek with a bad haircut, there was a cute girl in the mirror. My third wish, a wish so improbable and so desperate that I had never consciously acknowledged it, had been granted.

***

Late in August Walter Cronkite reported that thousands upon thousands of hippies had descended on a farm in upstate New York for a three-day music festival. The six o’clock news never showed any of the music, only the miles of traffic and abandoned cars and then finally half-naked people rolling about in the mud, Walter tut-tutting away like a maiden aunt. It looked amazing, the most fun a teenager could have. I watched desolate, knowing my tribe was out there, listening to the music I loved, taking the drugs I wanted. As always, life was happening somewhere else.

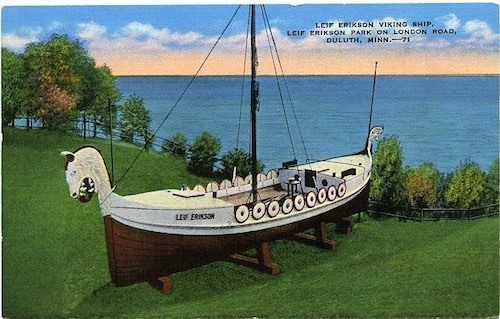

But Woodstock unlocked something in the teenagers of Duluth. As if summoned by the Pied Piper, throngs of kids coalesced in scraggy bands on the rolling green lawns of Leif Erickson Park, boys strumming guitars and girls twirling their long gypsy skirts around and around. At the downtown Woolworth’s next to the turtle tank I found a rack of buttons with peace symbols and “Make Love Not War” that I pinned on the lapel of my fringed jacket. The Age of Aquarius had reached Duluth.

On the first day of school, I walked down the East High hall into a different world. A whole subset of druggies and hippies had sprung up like dandelions. There were dozens of kids in tie-dye, patchouli oil was used way too liberally, and almost every boy, including the jocks, had hair that brushed the collars of their shirts.

I made my way up to the third floor, to Mr. Burrows’ two-hour, buttock-killing, smart-kids-only, enthralling American History and Literature Class, an educational jewel that was more fascinating and more informative than any college course, even if it did hew to the Famous White Men model, with nods to Anne Bradstreet and Emily Dickenson. As I slipped into my usual seat next to Nancy Erman, she nudged me, nodded her head sideways, and daringly whispered “New boy. Your type.” Mr. Burrows’ thundering brow turned toward Nancy at this violation of his rule of absolute silence. She gave him a twinkling Nancy smile, and, mollified, Mr. Burrows went back to the chalkboard to write: “A true relation of such occurrences and accidents as hath hapned in Virginia. John Smith, 1608,” and we were off to the races, three hundred years of history and literature to cover in nine months.

I snuck a glance in the direction Nancy had nodded in. Sitting all alone against the back wall, lit like a Renaissance angel under the slanting autumn light that poured in through the diamond-paned windows, was a boy with long dark hair that reached his shoulders and John Lennon wire-rimmed glasses. Beneath the glasses and the hair was a cherubic face, as round and sweet as an apple, a face that wore a serious, studious expression that reminded me to turn, reluctant and hopeful, back to my own interrupted note-taking on the founding of Jamestown.

This boy was Michael Vlasdic, my first love.

He was heart-meltingly handsome, and I knew that he had to be smart to be in Mr. Burrows’ advanced class. Two hours later, when Mr. Burrows allowed questions and comments, Michael sat silent, although I did see him occasionally smile, revealing adorable dimples that would be so much fun to kiss.

Michael Vlasdic was also in my lunch period, where I clocked him sitting at the back of the raucous East cafeteria with Roger Dennison, another rare new kid, who was good-looking in a blond, high-cheeked, Slavic way despite a nose like a jagged ski run, and with my old friend Eric Olson from elementary school. Eric was now known as Needle, not for his use of intravenous drugs but for his extreme skinniness. Roger and Needle both sported nicely shaggy hair, though not as long as Michael’s.

A year ago, I would not have been able to walk within ten feet of a boy I liked without my stomach flipping over and my tongue gluing itself to the roof of my mouth. But good luck and bad experiences had given me confidence. I had shed my virginity and my goofy glasses and I had Michael Vlasdic in my sights.

The new, sophisticated me plopped down uninvited among the three boys, making sure that I was next to Michael, and finally put my mother’s advice—“Just walk up to a boy, say hi and start talking”—to the test. I smiled, asked Roger where he was from (Colorado, his father worked for the Air Force and had been transferred to Duluth’s tiny base), talked to Needle, another smarty pants, about our classes, and finally turned to Michael and said “I like your glasses.”

I watched his face and my heart gave a small thump. I thought, I know this person, I have been this person, struck dumb at the prospect of talking to the opposite sex. It was as if I could read what was going through Michael’s mind: “What does that mean? Is she making fun of me? Or should I say thank you and then say I like your shirt?” I could tell he was weighing all his options as if one wrong word could open up the cafeteria floor and send him down to Hades, while the other kids laughed and pointed at him.

It was too painful. I jumped back in and carried the conversation single-handedly (look mom!) until the bell rang to send us off to class. That was also my signal to make my move. “So Michael,” I said, “What are you doing Saturday night?” All three boys exchanged shocked, mystified looks, but there was none of the horror that I used to see on the faces of the boy I asked to dance at Cotillion.

Michael quietly admitted that he had no plans for Saturday night and then looked as if he were waiting for a stinging, “Oh I’m going to a fun party” from me.

I took a breath and said, “Do you want to go out, go do something?” A beatific smile crossed Michael’s face, revealing those adorable dimples that I could have kissed right there and then. I took this as a yes. We scribbled phone numbers in each others’ notebooks and I left feeling that little squeeze of my heart and tingling between my legs that I got listening to Robert Plant moan “The Lemon Song” or re-reading the dog-eared pages in my copies of Lolita and Candy that I hid between the mattresses.

North Country Girl: Chapter 27 — Broomball and Other Activities

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir. The Post will publish a new segment each week.

On weekend nights, kids meandered from one car to the other at London Inn, asking each other “Where’s the party?” All too often parents selfishly refused to leave home, or a drunken debacle the weekend before had resulted in Wendi Carlson’s mother forbidding her to have friends over, or Mr. and Mrs. Anderson were waging a minor, and ultimately unsuccessful, offensive to take back their basement from East High’s sophomore class.

So my gang of girls ended up doing a lot of drinking al fresco, even when the snow piled four feet high and the temperature dropped to zero. I staved off the cold in long underwear and my toasty army surplus green parka with a neon orange lining, the hood trimmed with fur from some strange beast, the exact same jacket worn by all my friends; when we gathered outside to party, we looked like some weird winter drinking team.

The multiple layers we wore underneath that parka kept us warm, but also made peeing a two-girlfriend job, one to hold you up so you wouldn’t fall bare-assed into the snow and one to block the view from curious teen boys, as the process took a while. You had to unzip and then shove down the three layers of jeans, long underwear, and panties past your knees, before you could grasp the arms of Friend Number One, lean back till your butt was almost touching the snow, and finally feel that hot blissful stream that you hoped missed your boots.

Drunken tobogganing on the hilly ninth hole of Northland Country Club was a favorite winter activity until Andie James knocked out her upper incisors when she shot head first off the sled and we had to deliver her bloody-mouthed and smashed on Tango Orange Flavored Vodka to her distraught parents.

We then took up drunken broomball, the only team sport I have ever enjoyed. The first half of drunken broomball was collecting brooms. We drove up and down the dark snowy streets of Duluth, peering at each porch and stoop illuminated under a circle of pale light til we spotted one that had a simple, regulation, round-handed, yellow-bristled wooden broom leaning against the house, kept there to sweep fresh snow off the steps. Wendi Carlson — no one else was brave enough — leapt out of her well-earned shotgun seat, ran close to the ground in a Groucho Marx crouch to the target house, snatched up the broom, ran back to the car, threw the broom inside, trying not to whack anyone, and hopped in while we all yelled “Go go go!” and the White Delight peeled out.

When we had gathered the same number of brooms as girls, we drove down to the Congdon Elementary ice rink, lovingly created and maintained by Mr. Swan, the scary janitor, every winter. The rink was totally deserted at night, faintly lit by the street lamps and stars. We stuck bottles of Night Train and Tango and Mad Dog and occasionally an actual real bottle of Southern Comfort in a rink-side snowbank and grabbed up our brooms. We slipped and slid skatelessly around the ice, laughing hysterically, falling on our asses, and occasionally swatting a volleyball in the direction of a hockey net. There were many breaks for drinking and helping each other pee. It was always hard for me to remember which net my team was supposed to be aiming at, but I rarely touched broom to ball anyway. I was there for the girls, for the drunkenness, for the laughter. We didn’t keep score; it was like the caucus race in Alice in Wonderland. Suddenly the game would be over and we would head back to the London Inn, thoughtlessly leaving both bottles and brooms scattered on the ice for Mr. Swan to clean up the next morning.

Once the snow was off the ground and the temperature reached a balmy fifty degrees, new drinking venues opened up. Former Girl Scouts and YWCA campers, we built raging bonfires on the lakefront, which attracted boys from miles around, and which I hope we properly extinguished. There was also the abandoned one-room Lakeside train depot, which offered shelter even if it had a faint whiff of hobo piss. This was a popular spot as it was where the trains slowed down before entering the yard. A test of manhood (or drunkenness) was to run alongside the train, jump and pull yourself up the ladder, and ride a few hundred feet down the line before launching yourself off into the cinders that bordered the rails.

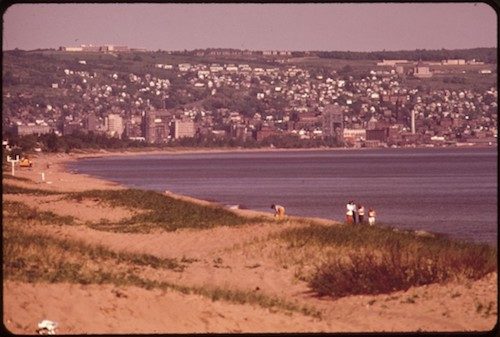

Finally, it was Duluth summer, when we would shiver in our bikinis at Park Point beach trying desperately to get a hint of a tan, playing Spades, listening to WEBC on the radio, singing along to “My Cherie Amour” every time it came on, which was twenty times an afternoon, gossiping about boys, and smoking (except me). There were trips out to rustic lake cabins, with smelly outhouses and rooms lit by kerosene lamps, and hopefully, parents back in the bustling city of Duluth, so we could carouse freely, long into the twilight evening, the sun still beaming off the lake water at ten at night. If we were lucky or if someone had dropped a hint, groups of boys discovered our location and arrived by the carload, bearing more bottles of booze and sleeping bags to cuddle and steal kisses in.

With all those other pleasurable activities, enjoyed in the company of my solid band of girlfriends, every week I crossed my fingers and wished that Doug Figge would have to spend both Friday and Saturday nights over the Fryolater. I liked the idea of a boyfriend much more than the boy himself.

***

Before the end of my sophomore year, I received a letter from Global Citizenship, inviting me back for another session of junior international diplomacy. Most of my girlfriends had landed summer jobs; at 15 I was too young for anything but babysitting, which I despised. I had a lot of summer days to fill, so I signed up for another go at becoming a Global Citizen, deciding that the hours spent lost in the black and white visions of Fellini and Bergman more than made up for the tedium of running imaginary countries.

The letter also informed me that this year’s Global Citizenship class would count toward high school graduation credits. Doug Figge listened to my ramblings about last summer’s course — the fabulous movies, the atomic bomb attacks — with half an ear, as he was busy trying to wriggle his hand inside my pants, but he took notice when I mentioned the credit. The next day I found out that Doug, John Bean, and Joe Sloan had all signed up for Global Citizenship.

Joe Sloan had come back from his strict boarding school with a serious hallucinogen habit, which he immediately passed on to Doug and John. Since I was unable to smoke a joint I was never offered so much as half a tab of acid. When not working or at Global Citizenship, the three boys, with me in tow (Mary Ann Stuart was MIA that summer), got high in Joe Sloan’s basement, blasting Cream and looking at the walls. There is no worse hell than being stuck in a room for hours with people who are tripping so hard they forget to turn the record over.

That summer’s Global Citizenship class was a bust. There were the two bright young men from last year, now even more hopeful that all the made-up nations and the kids running them could learn to live in peaceful harmony. The nuclear option had been removed from the game, making it even more tedious and probably closer to what the real UN is like. And instead of those wonderful foreign films, there was Photography. We were broken into groups of four or five, given one (1) camera per group, and ordered to create a slide show depicting a social issue. I don’t know what kind of Dorothea Lange images these young men expected in prosperous Duluth; what they got were mostly photos of the town’s three most prominent winos and a few liquor store Indians.

I was stuck with Doug and John and Joe, who decided our group’s topic would be drugs. I was not given a vote; in fact, I never even got to touch the camera. The boys completed our assignment without ever having to leave Joe Sloan’s basement. They took photos of album covers.

That was our slide show on a social issue: drug-inspired album covers — “Tommy,” “Their Satanic Majesties Request,” (with that weird wavy plastic insert), and “Court of the Crimson King” — one slide clicking into focus after the other, with “Crystal Ship” by the Doors as the soundtrack. After the lights went back on, the two nice young men shook their heads, expressed their disappointment in our group, and told us we would not receive credit for the class. One of the teachers pulled me to the side later to ask, “Are you okay? Are those boys giving you drugs?” If only.

My mother was also taking a class that summer at the university, having decided to resume her college education, which had been interrupted by my conception and birth. Three afternoons a week I had the ultimate teenage luxury: a parentless house. All my girlfriends who were off work came over to sit around the kitchen table, fog up the breakfast nook with cigarette smoke, and make plans for that night (“We’ll meet at the London Inn”). If my sisters were also out of the house, I’d be with Doug on the living room couch, him splayed on top of me, tentacled like an octopus, hands everywhere, oily-faced and hot-breathed.

Why didn’t I just break up with him? Why did I allow him to maul my tiny bosoms when it gave me no pleasure at all? Why did I give in to Doug’s pleas to “Just touch it, just put your fingers on it?” so he could have the spurt of pleasure while all I got was a sticky hand?

I kept hoping that somehow Doug would magically disappear and Joe Sloan would finally realize that we were meant for each other. Or that someone would say, “Here, Gay, here’s a tab of acid,” and make my time with Doug more interesting.

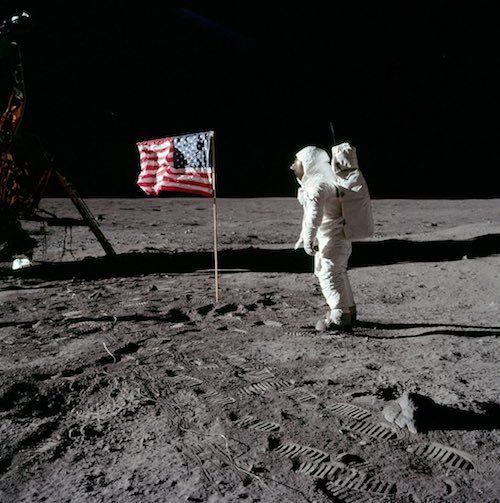

What I got was Doug’s needy grindings of his crotch on my hip bones, his crappy kissing, and his claim of “I love you,” supposedly the magic words that would make it okay to have sex with him. All of which wore me down and wore me down until I finally succumbed on July 20.

Joe Sloan and John Bean were busy in Joe’s basement. Joe had just received a mail order kit to make fireworks, and he and John, pupils the size of pinholes, were cackling uncontrollably as they spilled gunpowder about a small work room. I don’t know if they were making bottle rockets or M-80s; I did know that I did not want to be around in case someone lit a cigarette. So when Doug stuck his tongue in my ear and drew me away up the stairs, I did not object. We crept up the back stairs to a long forgotten room, maybe a former maid’s quarter, with a small window angled under a gable, a single mattress, and a black and white TV on a dresser.

Doug, true to his upbringing, could not resist turning on the television.

“Look!” I cried. “It’s the moon landing!” Doug looked and then fell on top of me, yanking away my tee shirt and shorts. Oh the hell with it, I thought, let’s just get this over. Doug thrust his way inside me while I pretended it didn’t hurt. I turned my head towards the TV and watched Neil Armstrong take his first step on the moon while I said goodbye to my virginity. One small but necessary step for womankind.

For years I had been dying to have sex; I expected the transcendent experience described in my favorite dirty books, not one where my most vivid memory is of an astronaut. Years later, I still felt queasy every time I saw MTV’s logo of a man planting the flag on the moon.

There was no rubber; Doug had never offered to get one, and I had no idea of how to bring up the subject. I took the idea that I could get pregnant from this awkward coupling and stuck in somewhere in my brain where I wouldn’t see it.

When it was finally over, Doug looked at his watch, but not to time his performance. “I have to get to work,” he said, and pulled on his pants. I did not look back to see what bodily fluids we had left on that lonely bed. Doug drove me home, and I called Wendi Carlson and complained. She assured me that every girl’s first time was awful, and that even though I was sore and still finding drops of blood in my panties, if I wanted to eventually enjoy it, I should keep on having sex with Doug.