The Art of the Post: The Post’s Rockwell and MAD’s Drucker: Two Great American Artists

Two great American magazines — The Saturday Evening Post and MAD magazine — studied each other across a wide gulf of respectability.

Each was an important cultural institution. The Post was the bastion of respectable middle American values, designed for a traditional and patriotic audience. MAD was a subversive humor magazine designed to appeal to the mischievous children of the Post’s readers.

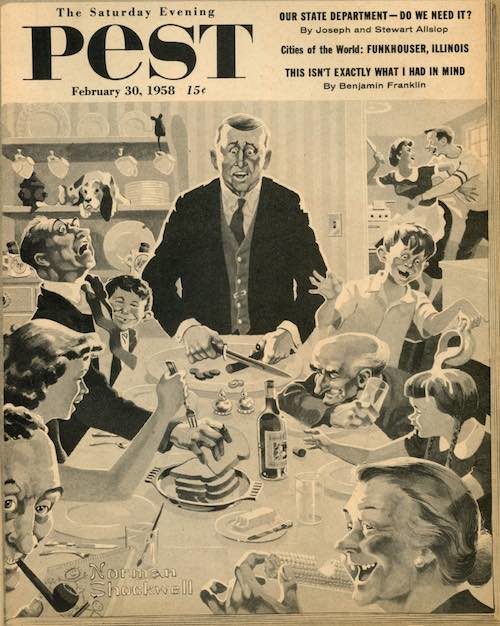

In 1958, MAD satirized the Post in a feature article, “The Saturday Evening Pest.”

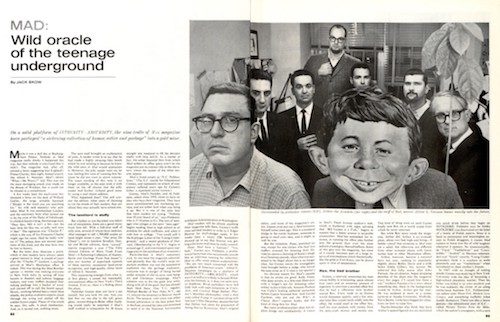

The Post, on the other hand, labeled MAD magazine the “Wild Oracle of the Teenage Underground” in their December 21, 1963, issue:

Despite their obvious differences, the two magazines had several parallels. Both had millions of subscribers and were hugely influential. Both attracted top writers and illustrators. And both came to be known for a special artist who spent most of his career with the magazine, becoming the face of the magazine to the public.

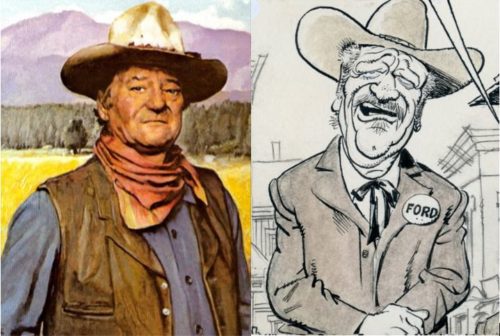

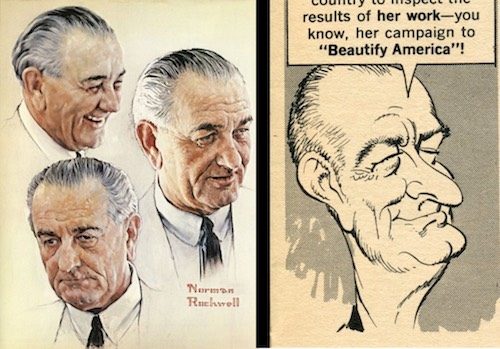

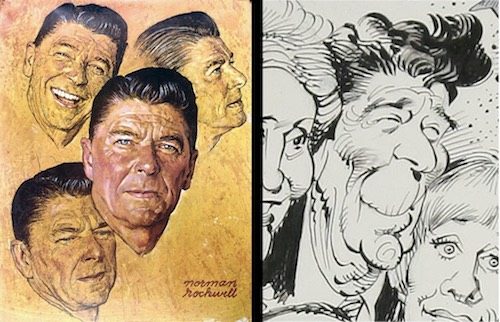

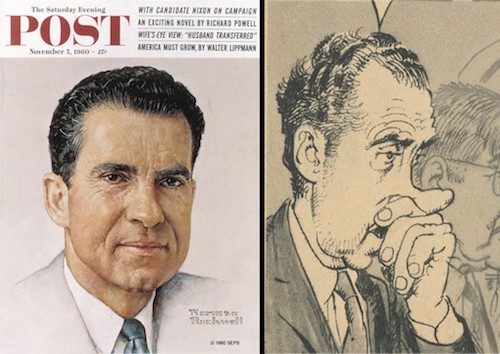

For the Post, that artist was Norman Rockwell. He dedicated most of his life to the Post, painting 322 covers over 47 years. His familiar look and style became synonymous with the Post for millions of Americans.

At MAD magazine, Rockwell’s counterpart was Mort Drucker, who worked for MAD for more than 50 years. Drucker became internationally known and respected as a genius of American humorous art, just as Rockwell became known as a genius of traditional American illustration. In the book, MAD’s Greatest Artists: Mort Drucker (Running Press, 2012), famed film director George Lucas says, “Mort Drucker’s …. caricatures are the best, and he is the artist that defines MAD for me.”

Through many years, through all kinds of trends, fads and political shifts, Rockwell and Drucker recorded opposite sides of the great American parade with brilliance and insight. They created countless pictures of politicians, movie stars, and everyday American scenes.

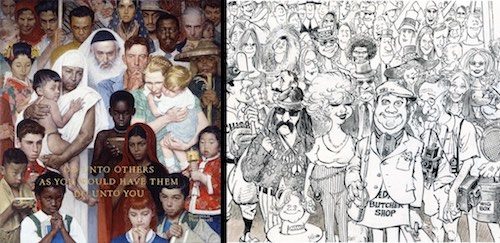

The two artists weren’t so different. Rockwell worked with a cartoonist’s sensibility, always looking for a humorous situation for his Post covers to provide a snapshot of American life. Drucker was something of an illustrator, a formidable draftsman who was able to draw and paint with great accuracy in addition to his funny caricatures.

Both artists worked in a benevolent, humanistic style. When I interviewed Drucker for this column, he explained why he tried not to make his caricatures angry or mean: “If someone has a big nose and you focus just on that, then you’re really cheating because you’re not getting to the nitty-gritty of the person. You’re taking just a negative feature and building on that and I don’t see the point in it.” During periods when it was fashionable to be cynical, this caused critics to accuse Drucker and Rockwell of being “corny.” But both artists chose a more buoyant, optimistic approach to their subjects. They both seemed to recognize that, in the words of Thoreau, “The only way to speak the truth is to speak lovingly.”

Their empathy may be the secret of their miraculous staying power. They remained popular for decade after decade while other artists came and went.

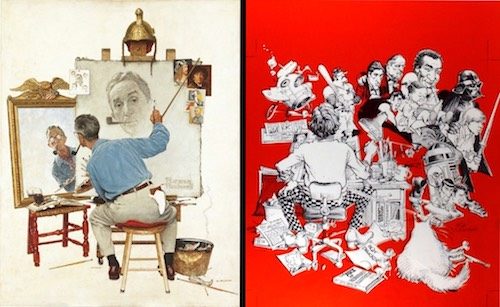

Most importantly, both Drucker and Rockwell were driven perfectionists. They maintained high standards decade after decade, working hard to do the best they possibly could, and filling their pictures with extra touches long after other artists would consider the picture finished.

As a young artist starting out, Rockwell painted “100%” in gold numbers on his easel to remind himself that he should never succumb to the temptation of getting by with less than his very best. Similarly, Drucker told me, “When you get adulation from people who want to be artists, you can’t let them down by not being the best you can be. Because they’re looking at you to be the artist that they can be. So you strive to be good to get that knowledge to them so that they will be the best they can be.”

Neither artist dreamed of taking shortcuts just because they worked for a commercial magazine printed on inexpensive paper rather than for a fancy art gallery. As a consequence, their work transcended their commercial platform and is admired around the globe today.

In view of the parallels between Rockwell and Drucker, it is not surprising that two of the greatest visual storytellers of the modern era, Stephen Spielberg and George Lucas, singled out both Rockwell and Drucker for praise. Spielberg and Lucas collect the original art of Rockwell and Drucker, and both speak enthusiastically about the importance of the two masters.

When Spielberg and Lucas loaned their Rockwell collections for public exhibition in museums, NPR reported, “Lucas and Spielberg have hung Rockwell’s pictures all over their homes, offices and in storage….”

The two directors explained to NPR what they loved about Rockwell:

“He wasn’t cynical. He wasn’t mean-spirited,” Spielberg says.

“He captured the American ideal of what we wanted to believe we were,’ Lucas says, finishing Spielberg’s thought. ‘We weren’t any better then than we are now, but by having the ideal out there — what we aspired to — it made it so that we could try to be more than what we were.”

Despite the fact that MAD poked fun at American institutions, Drucker was never “cynical” or “mean-spirited” either. In MAD’s Greatest Artists: Mort Drucker, Stephen Spielberg said, “Mort Drucker’s timely sense of parody mixed with commentary first made me aware of the culture of our generation. Mort’s irreverent and historical caricatures have never been nor will they ever be equaled.” George Lucas said, “Mort Drucker’s signature artwork captures and exaggerates the world around us and the people in it in a way that makes them more real…. When I had to choose an artist for the American Graffiti poster, Mort was the first and only person who came to mind.”

Even though the Post and MAD saw the world from very different perspectives, their two great artists shared artistic values that transcended those differences and helped to build lasting reputations for the artists and their magazines.