Narcotics Hysteria and the Criminalization of Drug Addiction

What is a proper reaction to reports, in the 1940s and ’50s, that imply the existence of 4 million drug addicts in the U.S.? One reaction — the one ultimately chosen the federal and state governments — was to pass stricter new laws and regulations that sought out those involved with both using and selling drugs and locked them up, away from civilized society. Another way, the one championed by Dr. Laurence Kolb of the U.S. Public Health Service, was to check those numbers and find out if the problem was really so widespread.

To be sure, there was a narcotics problem. At the end of the 19th century, opium and its derivatives — like heroin, morphine, and laudanum — had found their unregulated way into hundreds of over-the-counter pain relievers for everything from teething to arthritis. People were becoming addicted, and doctors were starting to notice.

In 1914, the Harrison Act limited access to opiates and cocaine. Clinics were set up to help the addicted under the care of professional supervision. But over the next 10 years, most of those clinics closed as political positioning and journalistic sensationalism shifted public opinion away from helping addicts and toward criminalizing them. New laws and their interpretations meant that addicts seeking medical help were more likely to face conviction than convalescence.

Amid the hysteria, in 1924, Dr. Kolb published his report for what would become the National Institute for Public Health, estimating that addicts in the United States “never exceeded 246,000.” Drug addiction was a problem, yes, but not as great a problem as headlines led people to believe. What’s more, Kolb argued, our reaction to the drug problem was wrong-headed.

In 1956, Dr. Kolb wrote “Let’s Stop This Narcotics Hysteria!” for the Post. In the 32 years since his original report, our approach to drug addiction hadn’t changed much. In this article, he argues for a more enlightened view, showing how treating all drug addicts as criminals makes little sense medically, economically, or socially. He also offers an alternative.

Today, the so-called war on drugs continues, and the outlook doesn’t seem much different. According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, nearly half of federal prison inmates are there for drug violations. A Justice Policy Institute study has shown that treating a drug addict costs, on average, $20,000 less per year than imprisonment. Given the cost of incarceration, punishment instead treatment is not simply shortsighted and vengeful, but it’s also impractical.

Let’s Stop This Narcotics Hysteria!

By Laurence Kolb, M.D.

Excerpted from an article originally published on July 28, 1956

Many years ago, when I was a stripling, I sat listening to a group of elderly men gossiping in a country store. They were denouncing the evils of cigarette smoking, a vice that was just coming in.

This store had on its shelves a jar of eating opium, and a carton of laudanum vials — 10 percent opium. A respected woman in the neighborhood often came in to buy laudanum. She was a good housekeeper and the mother of two fine sons. Everybody was sorry about her laudanum habit, but no one viewed her as a sinner or a menace to the community. We had not yet heard the word addict, with its sinister, modern connotations.

Since those days, public opinion has done a complete about-face. The “sin” of smoking cigarettes, in 50 years’ time, has become a socially acceptable habit, while drug addiction has been promoted by hysterical propaganda to the status of a great national menace.

As an example, one prominent official has said that illegal heroin traffic is more vicious than arson, burglary, kidnapping, or rape, and should entail harsher penalties. Last May 31st, the United States Senate went even further, in passing the Narcotic Control Act of 1956. In this measure, third-offense trafficking in heroin becomes the moral equivalent of murder and treason; death is the extreme penalty, “If the jury in its discretion shall so direct,” for buyer and seller alike, whether addicted or not.

In my opinion, the lawmakers completely missed the point. For drug addiction is neither menace nor mortal sin, but a health problem — indeed, a minor health problem when compared with such killers as alcoholism, heart disease, and cancer.

I make that statement with deep conviction. My work has included the psychiatric examination and general treatment of several thousand addicts. I know their habit is a viciously enslaving one, and we should not relax for a moment our efforts to stop its spread and ultimately to stamp it out completely. But our enforcement agencies seem to have forgotten that the addict is a sick person who needs medical help rather than longer jail sentences or the electric chair. He needs help which the present Narcotics Bureau regulations make it very difficult for doctors to give him. Moreover, no distinction has been made, in the punishment of violators, between the nonaddicted peddler who perpetuates the illicit traffic solely for his own profit and the addict who sells small amounts to keep himself supplied with a drug on which he has become physically and psychologically dependent.

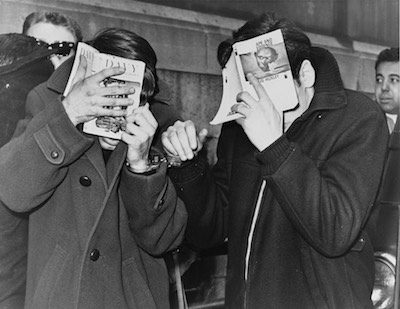

World Telegram & Sun photo by Herman Hiller.

Library of Congress

The Council of the American Psychiatric Association, in a public statement issued after the Senate passed its bill, declared that this and a companion measure introduced in the House, “represent backward steps in attacking this national problem.” The association, after listing some of the points I have just made, concludes by remarking that “additional legislation concerning drug addiction should be directed to making further medical progress possible, rather than discouraging it. The legislative proposals now under consideration would undermine the progress that has been made and impede further progress. Thus, they are not in the public interest.”

I was launched in this field of medicine in 1923, when the United States Public Health Service assigned me to study drug addiction at what is now the National Institute of Public Health. In 1935, I opened the service’s hospital for treatment of addicts at Lexington, Kentucky. Three years later I became Chief of the Division of Mental Hygiene, overseeing administration of the Lexington hospital and a similar institution at Fort Worth, Texas. And after retiring from the service in 1944, I continued to be active in psychiatry. So I know a great deal about addiction, and how perverse our attitude toward it has become.

Most addiction arises from misuse of marijuana, cocaine, alcohol, opium, or opium’s important preparations and derivatives — eating opium, smoking opium, laudanum, morphine, and heroin. Alcohol is a yardstick with which to measure the harm done by other drugs. There are 4,500,000 alcoholics in this country, and about 700,000 of them are compulsive drinkers who are on “skid road” or headed for it — gripped like opium addicts by psychological forces they cannot control.

Until recent times, millions of people in Asia and Africa were habitual users of opium. Dr. C.S. Mei, a physician and Chinese government official, told me in 1937 that there were about 15,000,000 opium smokers in China. He was interested in the anti-opium campaign because the slavish habit was lowering users’ diligence and industry. But he remarked that opium smoking had little or no effect on health and no effect whatsoever on crime.

Addiction is far less common among Western peoples, chiefly because of our preference for alcohol. At the highest point of drug addiction in the United States, 1890–99, when all kinds of opiates could be bought as freely as candy or potatoes, there was only one opium addict for every 300 of the population. Today we have about 60,000 addicts in the United States — that is, about one in 2,800 of the population. About 50,000 of them are addicted to opiates, mostly heroin, about 5,000 to opium-like synthetic drugs, and about 5,000 to marijuana. Cocaine, once widely used, has practically disappeared from the scene.

Lawmakers may feel that addicts as well as sellers deserve death, but few doctors would agree. I have in mind particularly a report issued in June 1955 by a group of prominent New York physicians, appointed by The New York Academy of Medicine to study the addiction problem. The gist of their report is that drug addiction is not a crime, but an illness, and that the emphasis should be placed on rehabilitation of addicts, instead of on punishment.

This committee deplores the fact that addicts are forced into crime by unwise suppressive methods. It recommends that, under controlled conditions, certain morphine and heroin addicts be given the drug they need while being prepared for treatment. For certain incurable cases, the committee advocates giving the needed opiate indefinitely at specially regulated clinics, although many physicians oppose using clinics in this way. My own proposal, which I shall go into later, would be to have such cases evaluated by doctors appointed for their competence in this field. The New York committee also recommends counseling services for patients after withdrawal treatment, to help them resist the temptation to return to the drug when stress situations arise.

A key fact to bear in mind is that the man addicted to an opiate becomes dependent on frequent regular doses to maintain normal body functions and comfort. If the drug is abruptly withheld he becomes intensely ill. In rare cases he may even collapse and die.

I once saw a woman who had come here from abroad, where she had been taking eight grains of morphine daily. Cut off from her supply, she got into an American hospital where suppression of the “drug menace” was more important than the relief of pain. She died in two days, due to sudden stoppage of the drug. There was nothing in the law to forbid giving this woman morphine to relieve her suffering, but propaganda about drugs had clouded the judgment of someone in authority.

The effect of opiates on the general health of addicts is not definitely known. There is a lack of positive evidence that a regularly maintained opium habit shortens life, but it probably does so, especially when large doses of morphine or heroin are used. The few reports that indicate harm are based on death statistics of groups of addicts, mostly opium smokers, many of whom started using the drug to ease already existing illness. Addicts in American jails undoubtedly have a high death rate. Some are repeatedly ill due to many periods of forced abstinence. Others, unable to buy enough food after paying for needed drugs, arrive at the prison gates half starved and a prey to infections.

In the 1920s, the average American addict was taking six grains of morphine or heroin daily. It was impossible to find harmful effects among those who got their dose regularly. I have known a healthy, alert 81-year-old woman who had taken three grains of morphine daily for 65 years. The well-fed opiate addict who regularly gets sustaining doses is not emaciated or pale, nor does he have pinpoint pupils, as is popularly supposed. He cannot be recognized as an addict on sight.

Cocaine is another story. It is fortunate that cocaine addiction is seldom seen nowadays, for excessive use of this drug causes emaciation, anxiety, convulsions, and insanity. Neither cocaine nor marijuana has the merit of making some neurotic people more efficient, as is the case with opiates. And the use of marijuana or cocaine can be discontinued abruptly without bringing on uncomfortable or dangerous withdrawal symptoms. When cocaine is suddenly denied a large user, he simply goes into a deep and very prolonged sleep. Therefore, there is no reason why any cocaine or marijuana user should be allowed to have his drug, even for a short time.

In an earlier period, opiates could be bought anywhere in America without restriction, and many people became addicted. Still, they worked about as well as other people and gave no one trouble. Only the physicians were concerned. They saw that the cocaine user and 60-grains-a-day morphine addict were injuring their health. More important, they saw thousands of unhappy opium eaters, opium smokers, and laudanum, morphine, and heroin users seeking relief from slavery, and often failing to get it.

Distressed by the evil, physicians advocated laws to prohibit the sale of opiates without prescription. By 1912, every state except one had laws regulating in some way the prescribing or sale of opiates and cocaine. As a result, the number of addicts fell from 1 in 300 of the population during the decade 1890–99, to 1 in 325 during the next decade. And after 1909, a ban on smoking opium caused a further decline in addiction.

Until 1915, however, addicts who needed opiates to continue their work in comfort could get their supplies legally without much trouble or expense. Then the Harrison Act became effective. This important federal law had both good and bad effects. Unable to get opiates, hundreds of addicts were cured by deprivation. These were mostly normal or near-normal people who were not seriously gripped by the psychological forces which hinder treatment of neurotic addicts and drunkards.

The bad effect came through unwise enforcement of the law. Physicians thought they could still prescribe opiates to addicts who really needed them for the preservation of health or to support the artificial emotional stability which enabled so many addicts to earn their livings. However, physicians prescribing for such people wound up in the penitentiary. Inability to get opiates brought illness to many hard-working citizens, and illness cost them their jobs. Some of them committed petty crimes to procure narcotics.

To remedy the situation, narcotic clinics were established throughout the country, where addicts could get needed drugs. Practically all of these clinics were forced to close by 1923. They had not been well run, but the chief reason for closing them was that addiction had become a crime, by legal definition.

The arrests of physicians, some of which were justifiable, and the sending of hundreds of addicts to prison, brought about a perversion of common sense unequaled in American history. Uncritical observers concluded that opium caused crime. The sight of so many law-abiding citizens applying to the clinics for help, instead of arousing public sympathy, was interpreted as evidence of moral deterioration, calling for increased penalties. The stereotype of the “heroin maniac” was born.

The number of addicts continued to decline. In 1924, the United States Public Health Service reported there were only 110,000 of them. By 1925, however, propaganda had led people to believe that there were 4,000,000 addicts in the country, and our fancied heroin menace was in full swing.

An ex-congressman appeared before the Senate Committee on Printing in 1924 to urge publication of 50,000,000 copies of an article entitled “The Peril of Narcotics — A Warning to The People of America.” He wanted a copy in every home.

Among other strange things, the article warned parents not to allow their children to eat away from home. If they did, it was said, some other child — a heroin maniac — might inject the drug into an innocent-looking titbit; whereupon the child eating it might instantly become an addict and join in a campaign to promote heroin addiction among other children. A Public Health Service physician persuaded the committee that this was nonsense, but propaganda about the heroin menace continued.

By Willis Kent Productions (The Cocaine Fiends (1935) at the Internet Archive) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

When American physicians advocated laws regulating narcotics, they had in mind the kind of laws in force in most Western European countries. What our physicians did not foresee was that they would be bound by police interpretations of the regulations; and that doctors who did not accept police views might be tricked into giving an opiate to an informer, who pretended to need it for pain or disease. Conviction meant that the physician went to prison.

Europeans regulate narcotics, as we do, but they are not alarmed by addiction, as we so obviously are. They have never lost sight of the fact that, as a great English physician wrote in the 17th century, “Opium soothes, alcohol maddens.”

In 1954, England controlled the illegal-narcotic traffic with the conviction of only 214 persons, 74 for opiate violations, 140 for violations involving marijuana. In the same year 12,346 persons were convicted in the United States for similar offenses. Allowing for differences in population, we had about 14 times more convictions than the English. Prison sentences meted out here ran into thousands of years — a fact that zealots boast about. In England, light sentences sufficed to discourage illegal traffic — 28 days to 12 months for opiate offenses, 1 day to 3 years for marijuana violations.

England’s sensible, effective policy is in sharp contrast with what goes on in the United States. I became well acquainted at the hospital in Lexington with a paralyzed, bedridden man who had been sentenced to four years for a narcotic violation. Just how he could be a menace to society was never clear to me. In Europe he would have been allowed to live out his last days in comfort. Only in the United States must addicts suffer and die or deteriorate in prison.

Unreflecting and sometimes unscrupulous people — and newspapers too — have contributed to the hysteria about drug addiction. News items reporting the seizure of “dope” frequently exaggerate the contraband’s value. One “$3,000,000 seizure” of heroin which made headlines was actually only enough to last seven six-grains-a-day addicts for a year. To justify the $3,000,000 figure, heroin would have to bring $196 a grain. Some addicts do spend from $5 to $10 a day on the habit, but few can afford it; hence the sickness and stealing.

Distorted news has prepared the public to support extreme measures to suppress imagined evils. When legislators undertook last spring to do something about the so-called drug menace, federal law provided two years in prison for a first-time narcotic-law offender. The minimum for a second offense was five years, and for a third, 10 years, with no probation or suspension of sentence for repeaters. The Narcotic Control Act of 1956 proposed increasing penalties for heroin trafficking to a minimum of 5 years for the first offense, 10 years for the second offense, life imprisonment or death for the third offense.

What happens under such laws? In one case, under the old law, a man was given 10 years for possessing three narcotic tablets. Another man was given 10 years for forging three narcotic prescriptions — no sale was involved. And another 10-year sentence was imposed on a man for selling two marijuana cigarettes, which are just about equal in intoxicating effect to two drinks of whisky. Extremists have gone on to demand the death penalty. They would do away with suspended sentences, time off for good behavior, the necessity for a warrant before search. They want wire tapping legalized in suspected narcotic cases, and they would make the securing of bond more difficult.

Existing measures and those which are advocated defy common sense and violate sound principles of justice and penology. There is nothing about the nature of drug addicts to justify such penalties. They only make it difficult to rehabilitate offenders who could be helped by a sound approach which would take into account both the offense and the psychological disorders of the offender.

Drug addiction is an important problem which demands the attention of health and enforcement officials. However, the most essential need now is to cure the United States of its hysteria, so that the problem can be dealt with rationally. A major move in the right direction would be to stop the false propaganda about the nature of drug addiction and present it for what it is — a health problem which needs some police measures for adequate control. Our approach so far has produced tragedy, disease, and crime.

The opinion of informed physicians should take precedence over that of law-enforcement officers, who, in this country, are too often carried away by enthusiasm for putting people in prison, and who deceive themselves as well as the public about the nature and seriousness of drug addiction. We need an increase in treatment facilities and recognition that some opium addicts, having reached the stage they have, should be given opiates for their own welfare and for the public welfare too.

Mandatory minimum sentences should be abolished, so that judges and probation and parole officers can do what in their judgment is best for the rehabilitation of offenders.

Medical opinion should have controlling force in a revamped policy. This is not to say that every physician should be authorized to prescribe opiates to addicts without restrictions. Some would be dishonest, others would be indifferent to consequences. Neither should the old type of clinic be re-established. A workable solution would be to have the medical societies or health departments appoint competent physicians to decide which patients should be carried on an opiate while being prepared for treatment and which ones should be given opiates indefinitely. Physicians would report individual cases to local medical groups for decision. And that decision should never be subject to revision by a nonmedical prosecuting agency.

The details of a scheme of operation should be worked out by a committee of physicians and law-enforcement officers, with the physicians predominant in authority. The various states could make a start by revising their laws to conform to actual health and penological needs. The medical profession could help by giving legislators facts on which to take action.

It should be stressed that it is easy to cure psychologically normal addicts who have no painful disease. Even the mildly neurotic addict is fairly easy to cure. Severe withdrawal symptoms pass within five days, although for several months there are minor physical changes that the patient may not feel or even know about, but which increase the likelihood of his relapse. The reason for the apparently large relapse rate among addicts is that a difficult group remains to be dealt with after the cured cases have been dismissed. The most difficult cases, perhaps, are neurotic addicts who suffer from migraine or asthma. Neurotics who have a painful disease are liable to have a psychic return of pain when their drug is withdrawn. When several treatments fail, such persons should be allowed to have the drug they need.

Thomas Jefferson, distressed over the ravages of alcohol, once said that a great many people spent most of their time talking politics, avoiding work, and drinking whisky. One wonders what he would say today if some muddled citizen warned him that opiates were rotting the moral fiber of our people. I suspect that he would advise his informant to take care, in walking down the street, lest he stumble over one of our 4,500,000 alcoholics and break a leg.

For a modern look at the problems of opium addiction, read “The Drug Epidemic That Is Killing Our Children,” from our September/October 2016 issue.

The Other Prohibition: Opiate Addiction in the Roaring ’20s

For as long as the U.S. has been a nation, it’s had a substance-abuse problem. In its early years, Americans consumed staggering amounts of alcohol: from 5.8 gallons of pure alcohol per person in 1790 up to 7.1 gallons per year by 1830. The misery and waste caused by drunkenness prompted many Americans to beg for laws that would outlaw liquor.

But alcohol was just one addictive substance. Opium was widely used before the 20th century, and its drawbacks were not recognized early. Throughout the 19th century, opium was a common ingredient in patent medicines that relieved any pain or discomfort, from teething to kidney stones. Ben Franklin and Thomas Jefferson were both known to imbibe laudanum — a preparation of alcohol and opium — to ease pain in their later years. Morphine, an injectable form of opium, was developed in time to ease the suffering of wounded Civil War soldiers, in many cases leading to lifelong addiction.

As the century wore on, people began to notice the addictive and detrimental effects of this drug and, well before the Prohibition Era, started limiting its use. In 1875, San Francisco passed the first anti-drug law, banning opium parlors — though this was as much an anti-Chinese law as it was anti-drug.

By the 1900s, the abuse of opiates had become so widespread that the federal government intervened. Under the Food and Drug Act of 1906, patent medicine manufacturers were required to state if their wares contained opiates, cocaine, alcohol, or other intoxicants. In 1914, six years before prohibition of alcohol, the Harrison Narcotic Act regulated the production, import, and distribution of opium, even among doctors.

But as Judge William McAdoo reports, it was still a serious problem that occupied much of his efforts in the New York City courts in the early 1920s. With a wealth of experience dealing with addicts, he describes the realities of their lives, their habit, their character, and their chances for recovery.

We tend to think that booze was what made the ’20s roar, but drug abuse added to the frenzy of those times.

Narcotic Drug Addiction as It Really Is

William McAdoo

Excerpted from an article originally published on March 31, 1923

There is an almost unbroken line of statements from drug addicts among men that they began taking drugs at public dance halls and all-night or late-at-night resorts. Here is a young fellow who has worked at an honest employment all day. He has swallowed a hasty meal, dressed himself up, gone to meet his steady-company girl, and the couple have brought up at a ball or a dance that will continue during the night. As the hours go on he becomes intensely fatigued, but he notices how wide awake appear the rivals for the favors of the other sex. They are apparently quite fresh, and are dancing and drinking without any signs of physical exhaustion. One of these young fellows whom he knows takes him out into the hall and drawing out of his pocket a small vial of heroin tells him: “Take a snuff of this. It will brighten you up.” So far as he is concerned, that is the beginning of the road to ruin, physical, mental, and moral. The addicts positively assert that a week’s use of a drug is sufficient to form the habit. This young fellow now has brightened up from the effects of the stimulant. The sleepy feeling has rolled away like a fog before the breeze, all his faculties are alert. He takes another dose in the morning before going to work — and this lamp that lights the dismal way to the caverns of despair has to be kept constantly fed during the years to come.

Sometimes you shudder as you look up at a stalwart young fellow riding on a steel beam on the 20th or 30th story of a building under construction, or tossing and catching red-hot rivets thrown as far away as 30 or 40 feet from the fire. It would seem unbelievable that this man, suspended in midair, with so cool a head and steady a nerve, was a drug addict, but in my experiences here I have found a few such cases. And the same is true of jockeys who have ridden horses for big stakes at the great race courses of the country. They will tell you that so long as they can get a full supply of the drug they have a steady nerve for these dangerous occupations, but they will readily admit that should they not get doped up, as they call it, before they undertake some especially hazardous task, they would undoubtedly fail. The lamp must be fed, the wick trimmed, and the fire alive, or it is darkness and ashes.

There is one thing that makes drug addiction much more serious than drunkenness from alcoholic liquors. The drunkard cannot conceal his vice. He may drink in secret, but he is sure to be found suffering from the effects of his drinking. If he is married, his wife and children will discover his condition; if he is unmarried, his parents and the other members of the family will know about it; and all their combined efforts, as may be found in painful cases, will not prevent detection by friends and neighbors. But the addict may be taking the drug for years without its being known by his family or immediate friends. This fact is so well known that it often gives rise to very unjust suspicions against persons who are entirely free from the habit. Mental deterioration, eccentricities in behavior, loss of memory, a vacant stare in the eyes— all these will frequently be regarded by unfriendly persons as indications that a man is taking drugs, whereas all these appearances may be from quite other causes.

Pitiful Cases

This inability to detect the addict makes the vice eminently a secret one. The drunkard has difficulty in hiding his bottle, but the addict carries a vial not larger than the small finger of the hand. If he takes hypodermic injections, the needle is easily concealed. If he cannot get the needle, which is prohibited by law, he will puncture a hole in his flesh and insert the fluid from an innocent-looking eye dropper, savagely punching the hole big enough to insert the end of the blunt dropper.

Addiction, therefore, can be carried on so secretly that the addict becomes covert and illusive in his manner, suspicious, untruthful, deceptive. When needing the drug and without money to purchase it or lacking opportunity to get it, he is likely to resort to courses involving crime, and to cruel deception of those interested in him. This is one of the very unfortunate circumstances connected with drug addiction which makes the addict in many cases the potential criminal, and when a real one, much more desperate and dangerous than those persons who are normal and under no artificial stimulus to the commission of crime.

Are Drug Addictions Curable?

Away back in the old days when drug addiction was unknown and alcohol and drunkenness were prominently featured in press and on platform, what pathetic things used to be said about the callous and unsympathetic nature of the drunkard; how indifferent he was to appeals to any remnants he had left of self-respect, to his obligations to those dependent on him as father and husband. However correct this view of the drunkard may have been, its truth has certainly been demonstrated with regard to the addict, so secretive and cunning in obtaining the drug and administering it to himself. His moral deterioration is much more rapid than his physical decay. He will lie and steal to get the drug, and he has ceased in an alarming degree to regard all social obligations. I shall refer hereafter to how hard, callous, cruel, and indifferent the addict shows himself in the presence of the appeal of mother and father, wife and children.

In outward appearance and demeanor, he appears to be as stoical as [James Fenimore] Cooper pictured his red warriors facing death. Self-respect and hope are dead, and a cruel and dominant selfishness has taken their place. He must have the drug or he suffers tortures beyond description. Life means the drug. Existence without it is impossible. Under the influence of the drug, he is blind to all surroundings except those channels by which he can obtain it. He is deaf to all pleadings. No sympathies can hold him back when the narcotic demands are pulling him forward. …

Is there any standard treatment by which the addict can be cured? Is there any hope in medication or even in surgery? Speaking as a layman and only in the light of experience, I am compelled to say that, depending on medical treatment alone, I think there is none. I mean by that that I have never heard nor do I know of any prescription or any treatment by medication that can cure a drug addict. It is quite true that the acute symptoms and seemingly the desire for the drug will, under custodial care, disappear for the time, but in a great majority of cases, once freedom is gained, the drug addict goes back to its use. In weaning the drug addict from his addiction there are two different treatments known to those in charge of hospitals in which these patients are segregated, and very often a drug addict will come here and ask to be sent to a particular hospital because he prefers the sort of treatment at that institution to the other. The end of both treatments, is, of course, the same — to purge the system of the poison, alleviate the disease, take away the craving, and bring the patient back to normal conditions. …

Practically all addicts admit that the usual course is to return to the drug after treatment and that they know that it is lack of self-control and the condition of mind that drive them to it. I make it a rule to impress on the addict when he leaves the hospital that he must never on any occasion go with another addict. “Do not keep company with any other person who is an addict or whom you suspect of being one, even if he is your own brother or a member of your family.” When two addicts get together, their relapse is inevitable. Mental depression, physical suffering, financial distress, comparison of symptoms—and they both go back to the old remedy, which they look upon as opening the door to an artificial and easeful world. Their cares and sorrows are temporarily dropped, only to be added to like compound interest on an unpaid debt.

Federal and Local Laws

The first wave of popular excitement about drug addiction in New York occurred in 1913, and as is usual in such matters the public was aroused from indifference to apprehension and alarm. Legislation was hastily drawn and readily enacted.

First there was the Harrison Law — federal — and then in New York State, there were various enactments and the creation of a narcotic drug commission; special committees of the legislature were appointed to investigate the subject, a great deal of testimony was taken and modifications of the amendments to the existing laws were made. Finally all were expunged from the statute book in 1920, leaving at this writing only the ordinance of the city of New York covering the subject, and now there is an organized effort to restore state legislation.

All the state enactments were restrictive as to use, and punitive. They allowed the doctor to prescribe for the ambulatory case — a person who goes to a doctor and gets a prescription for a drug and uses it without personal supervision by a physician or anyone else is called an ambulatory case — but they compelled the doctor and the druggist to keep strict records of prescriptions and sales. They made possession without a doctor’s prescription a crime. They compelled the reporting of cases to the Board of Health. They made provision for the institutions where addicts could be committed for treatment. They provided for the punishment of dealers and peddlers. I think they did not go to the root of the evil, but I am not condemning them. As for the present New York City ordinance, we could not very well get on without it.

Last year Congress appropriated $6 million to enforce prohibition against alcohol. The Treasury Department is now earnestly requesting that it be given sufficient money to enforce the Miller Act — that is, the drug-control law. It seems to me, considering this evil, that the enforcement of the Miller Act is certainly, without making comparisons, of vast importance to this country. As I understand it, up to this time no appropriation has been made to enforce the Miller Act.

Having taken part in many public discussions by doctors and laymen, representatives of organizations and individuals on this question of drug addiction and the treatment of addicts, I became convinced that if we are to go to the root of the evil, so far as the law is concerned, it must be by way of federal legislation.

The federal law, known as the Harrison Act, passed in 1914, aimed chiefly at controlling the sale and distribution of narcotic drugs within the United States and required of druggists and physicians that they should make returns of their actions with reference to these drugs on blanks furnished to them. Practically it was intended that the doctor should act in good faith as to the diagnosis and prescribe professionally in decreasing doses, and not merely cater to the craving of the addict; and that the sales by the druggist should be strictly inspected and accounted for.

Following this, New York enacted a law somewhat on the same lines and providing for a narcotic-drug commission. After this law was repealed, the health commissioner of New York City, having large legislative powers under the charter, called together a committee, of which I was a member, to formulate enactments covering the situation, to be added to the Sanitary Code, and these were the pertinent questions in connection therewith:

Can a drug addict be cured by getting prescriptions from a physician to be filled by a druggist while the addict is at large and without any custodial supervision?

Is it absolutely necessary, in order to undertake the cure and reformation of the drug addict, that he should be put in some institution under supervisory direction and custodial authority?

Conscienceless Physicians

Considering that at present most of the addicts — of the poor and working type, at least — buy their drugs from peddlers selling smuggled stuff, is this condition more dangerous than if the addicts resorted to certain types of conscienceless physicians with unrestricted liberty in prescribing? If the physicians were unrestricted in prescribing, would the addicts not get at the drug stores an article more potent than the smuggled stuff and for less money, and would this not really increase the number of addicts?

Before that committee, a sharp line of professional opinion was exhibited by those physicians who were backed by official action of the American Medical Association, that a physician should only administer narcotic drugs and not prescribe them, against those who favored prescription and hospital treatment, private and otherwise.

The federal district attorney for New York presented the case of one physician who issued thousands of prescriptions during one year to drug addicts, evading the law with deliberate cunning, and who had reaped a fortune from this cruel and conscienceless practice. Of course men like him are not representative of the medical profession, but they were sufficient in number in New York to make it easy for any addict to get as much of the drug as he wanted. In one case prescriptions were kept in bundles ready for use, just as it is alleged they are now kept for the sale of alcoholic drinks.

The average addict who came to this office was obliged to get about four prescriptions a week, the doctor limiting the supply to about the amount the addict would use in two days. The prices for the prescriptions ranged from 50 cents to $2 or more. An addict came in here one cold winter day, without an overcoat and devoid of underclothing, who was getting prescriptions from one of these rascally doctors and spending all his wages as a mechanic, amounting to about $28 a week, and even more, for the drug. When I asked him why he did not buy himself some clothing, he told me that he had begged the prescribing doctor to give him prescriptions for at least two weeks in advance and reduce the rates so that he might get clothing suited to the season, and that the doctor had brutally refused to do so, taking the last cent this man had.

The ambulatory case can go to the doctor and get a prescription for the drug and use it, and then under another name he can go to another doctor, and so on; and I see no reason why under such a system he cannot accumulate even more of the drug than he needs for his own personal use. From the very nature of the case the patient requires constant professional supervision, and, above all, moral aid and encouragement.

Questions of Policy

With all this contention and debate and clashing of professional interests and the opposition of the big manufacturing, commercial, and distributing agencies who produce and sell the drugs, the subject became involved, and a Babel-like confusion of tongues ensued. The lay public, alarmed at the dangerously menacing situation, was naturally anxious to arrive at some conclusion as to what was the proper course to take.

Then, too, the question of prohibition with reference to alcoholic liquors became a stumbling block. Zealous prohibitionists believed that calling attention to drug addiction and asking for federal restrictive measures were attempts to divert public attention from that which they believe to be the only evil or at least the most important one. Some of them seemed to believe that the Wets were drawing a red herring over the trail in the talk about drug addiction’s being an evil equal to alcoholism. As a matter of fact, there is more hope for the reformation and regeneration of a drunkard than of a drug addict. Addicts who were barkeepers told me that they never took, nor had any inclination to take, a drink of alcoholic liquor, even when constantly handling it.

The health commissioner of New York finally adopted as part of the Sanitary Code the law that now obtains in this city with reference to drug addiction. It is in many features in line with the former state law, was very carefully drawn, and seems to answer the purpose for which it was intended. Violations of this code are punishable by fine and imprisonment. It prohibits the possession, sale, and distribution of cocaine or opium or any of their derivatives of Cannabis indica or Cannabis sativa or any of their derivatives, except under conditions set forth in the ordinance; and provides also that any addict may, on his or her own complaint, be committed to a hospital or other institution maintained by the city of New York; or to any correction or charitable institution maintaining a hospital in which drug addiction is treated; or to any private hospital, sanatorium, or institution authorized for the treatment of disease or inebriety; and that the addicts shall not make any false statements in obtaining prescriptions.

Out of all this welter of discussion, disagreement and clashing of counter interests I long ago became convinced, as I have said, that the remedy lies through federal legislation and a more sane and practical treatment of the addict.

The weakness of the original Harrison Act lay in the fact that it did not control importations and exportations. The law, in order to be effective, should check the incoming and the outgoing of opium and its derivatives. To that end the law known as the Miller Act went into effect in 1922. This, in my judgment, is the most important and effective legislation as yet on the statute books of either nation or state, but will no doubt require amendment as weaknesses may develop. Anyone who is interested in this subject will find a report on this law when pending, Sixty-seventh Congress, Second Session, H. R. Report 852.