Debbie Reynolds and the Divorce of the Century

Originally published March 26, 1960.

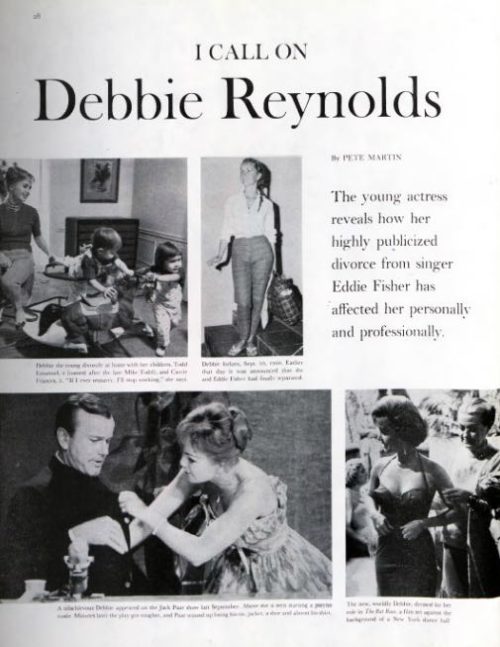

In the 1950s, Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher were one of Hollywood’s hottest couples — until Fisher had an affair with Elizabeth Taylor. In this article from March 26, 1960, Reynolds talked about how her highly publicized divorce affected her personally and professionally.

From its beginning, the courtship and marriage of Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher was proclaimed “The Sweetest Love Story Ever Told.” So it was only natural that the shattering of the Fisher-Reynolds spun-sugar dream castle was as screamingly publicized.

The fact that the darling little couple had become a triangle was regarded in certain circles as the biggest domestic tragedy since Douglas Fairbanks Sr. parted from America’s Sweetheart, Mary Pickford. The Fisher-Reynolds split reached its climax when Debbie agreed—after a year of hesitation—to a quick divorce so her husband could embark upon his second marital venture, this time with Elizabeth Taylor. Even then, however, the triangle refused to go away. In terms of cold, hard cash, the ordeal made the two ladies involved far more valuable at the box office. The price tag of the discarded wife leaped to $125,000 a picture, then to $250,000. The sum demanded for the services of the new Mrs. Fisher zoomed from $500,000 to $750,000—then to $1,000,000. Miss Reynolds soon signed a similar contract, earning $1,000, 000 for three television appearances.

Eddie Fisher on the other hand, has temporarily fallen from the high estate of having his own TV show, to playing the night-club circuit and doing a role in M-G-M’s Butterfield 8, a vehicle which also stars Miss Taylor, while talks are being held about a new TV show for him.

During the time when Debbie and Eddie, once the nation’s most publicized newlyweds, were engaged in becoming the nation’s most highly publicized divorcees, Fisher and Miss Taylor did most of the talking. I’d read various statements attributed to Debbie, but it was my thought that if I could get her to give me some of her ideas about the a air at first hand, it would still be newsworthy.

I remembered a photograph of her taken a few days after the news broke that she and Eddie were having difficulties. I mentioned that photo to her now. I said, “You looked like a teen-ager someone had just kicked in the stomach.”

“I know the picture you mean,” she said. “I remember it very well. It was taken after I had my children out for an airing, and when I came home there were a lot of strangers in my house— reporters and photographers. I didn’t even know what had happened. Then they told me that my marriage seemed to be definitely on the rocks, but I still didn’t get it. I remember saying, ‘It’s unbelievable that you can live happily with a man and not know he doesn’t love you.” When they took that photo, I had just finished changing my babies. I wasn’t thinking about how I looked. My mind was completely on another subject. When I saw that picture, I was surprised to see a couple of diaper pins still attached to my blouse.”

“How old were you when you and Eddie were married?” I asked.

“Twenty-three.” she said. “I had lived at home with my mother until then, so I was extremely inexperienced. I had to grow up very fast. Too fast. I don’t think that’s the best way to grow up. I think it’s the hardest way. But you certainly can learn that way, and it’s very thorough.”

What she said next sounded like something she had said to herself many, many times—and that she would say it many limes more. “As long as you can accept your experiences and digest them and not let them make you bitter or cynical or assume that life is always going to be that way, you’ll be all right. But if you allow them to make you cynical and bitter…” Her voice trailed off.

Strength of Character

I said I thought it would have been easy for her to become bitter. “I wouldn’t

let me be,” she said. “All my life I’ve hated people who complain about their knee-aches or their backaches. All they had to do was look around them to see people having it more difficult than they. If you consider the road a lot of other people travel, you can say to yourself, “Mine isn’t that rough!’”

I said to her, “In spite of all the stress, your statements to the press always seemed sound and sensible.” I thought of one statement of hers in particular. She had just finished shooting It Started With a Kiss in Spain, and on her way home friends in California reached her on the long-distance phone and repeated to her some of the remarks made during an impromptu press conference held in Eddie Fisher’s dressing room in a Las Vegas hold.

Some of Elizabeth Taylor’s remarks &mash; she was also present — were reported to Debbie as follows: “Eddie and I intend to travel and see as much of the world as we can, and we would like to travel as man and wife… We respect public opinion, but you can’t live by it. If we lived by it, Eddie and I would have been terribly unhappy through all this. But I can shamelessly say that we have been terribly happy… I am literally rising above it.”

When questioned about the possibility that Debbie might refuse a divorce, Elizabeth Taylor had answered, “At first Debbie was very much hurt, but I think now the hurt has left and she will consent to Eddie getting a divorce here.”

“When I came home from Europe, people kept asking me, ‘Will you give Eddie a divorce or won’t you?’ said Debbie. “It wasn’t a new question. Eddie had asked me before, and I had said no. But when I was coming home on that plane and I knew there would be people waiting for me at the airport. I prepared a last statement on the subject. It was this: ‘The position in which I am placed makes it necessary for me to give my consent, but they would have gotten married anyway.’”

She stopped for a moment. “Seems like all I did last year was prepare last statements. It was a very pressured year for me. In that one year I had enough emotions to wear me out.”

“You came through all right,” I said.

“If I did, maybe it was because I never told an untruth,” she said. “Whatever I said about my emotions was honest. What I felt must have been obvious: I can’t hide what I feel, I’d be better off if I could. For that matter, I’d be better if I didn’t feel so much.

“I tried to do everything and think of everything as I will five or ten years from now. If I had talked or acted as I felt at the moment, I might have said and done wrong things. Unfortunately our situation became public property. If it hadn’t, I think the three of us could have dealt with it in a mannerly way, I would probably have said no to a divorce, and perhaps it all would have worked out differently. But because it was dumped in the public’s lap by the other people involved, I had no choice.”

I said, “Some of those who have watched you whirling around of late with an ‘I-don’t-care’ air have told me, ‘Debbie seems to be having herself a ball. She must be having a great time being a bachelor girl again.’”

She said, “Whether what happens to you is for the best or the worst depends on what you make of it. You can be miserable or you can be happy, I think I’m having a great time now, and I think I’ll keep right on doing that, because I have so much to be happy about. Before I was married,

I wanted children. Now I have two children. They are all anybody could ever want. I have a lovely home; my professional career is looking up, I can travel everywhere, and I have very dear friends. So inside I’m happy. I really am, but it has taken time to acquire that philosophy.”

This article and other features about the stars of Tinseltown can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition, The Golden Age of Hollywood. This edition can be ordered here.