What Happens When You Talk About Politics in Person

The day before the Iowa caucuses, I boarded a bus at 5 a.m. to travel five-and-a-half hours to Dubuque, Iowa. A group of about 50 of us descended on the old river city to canvass potential voters. That is, we walked door to door and tried to convince whoever was inside to caucus for our candidate. I won’t say which candidate we were speaking for, but — as a hint — it wasn’t Deval Patrick or Michael Bennet.

I’ve canvassed before — for candidates and specific issues — but Iowa was a little different. To be sure, on the day before their highly publicized caucus in an election year that is looking more and more to be incredibly dramatic and hotly contested, most Iowans were sick of talking politics. Since the state is placed on a disproportionately high pedestal in the primaries, Iowans are routinely bombarded by throngs of presidential hopefuls every four years.

We arrived at the campaign office in Dubuque, and the local staff gave us a brief training in political canvassing. Of course, the goal is to persuade voters that your candidate is best for the job, but that isn’t always as straightforward as it sounds.

Like a significant portion of the country, I like to discuss politics online. Political discourse, between news comment threads, Facebook memes, and nonstop tweeting, ranges from enlightening (really!) to noxious to utterly untrue. The internet has transformed the way we talk about politics and government.

And, still, there is something to be said for a face-to-face conversation.

In spite of the potentially tremendous reach of a well-run online campaign, it doesn’t always have the same effect as the physical presence of a group of canvassers — especially if that group numbers in the thousands. Humans, in the flesh, talking to other humans can eliminate many perceptions of disingenuousness that percolate from the web. Of all the things I’ve been accused of while canvassing, being a robot has never been one of them.

After we received information on where we’d be canvassing, I set out with a group to the location. A local guy drove us to a suburban-looking neighborhood on the outskirts. He had grown up in Dubuque and was proud of his city, so it seemed as though he took the long route to show us its glowing golden-domed courthouse and the historic hillside cable-car elevator.

When he dropped us off, we marched up to the first house on our list. We had a name — let’s say Jason — and an age, 41. I knocked on the door, and we waited. This is the worst part of canvassing: awkwardly waiting on a stranger’s doorstep, feeling entirely out of place. When Jason opened the door, he confirmed our fears. He cut off our opening line, saying “You people have been here three times this weekend. If this keeps up, I’m going to vote for Trump.”

He closed the door on us, but it didn’t seem as though we were going to be successful in getting him to fill out a caucus confirmation card anyway, so we moved on to the next house. Door after door, we were met with disinterest, irritation, or no one at all. We began to think the endeavor was a bust. Even if we were passively distributing literature on Iowans’ front doors, it seemed as though we wouldn’t get the opportunity to turn out any voters.

Then we met David, a young dad who was just intoxicated enough to indulge us with friendliness and attention (it was the day of the Big Game, after all). He didn’t follow politics much, and he wasn’t aware of the caucus happening the next day, but he was interested in how policies could directly influence his family’s lives. We told David that we travelled hours that morning to talk to people like him because we believed in our candidate.

Even when people aren’t interested in following a political horse race, they can recognize genuine passion in a face-to-face conversation. A person who doesn’t devour the news might not have much of an impression of a presidential candidate’s tailored persona, but they can probably gauge the enthusiasm of a volunteer looking them in the eyes and describing their personal stakes in an election.

David was receptive, but we weren’t convinced that he would turn out to caucus the next day. It was a lot to ask: showing up in the evening to some church or college lecture hall and standing around for a few hours while people shuffle around the room to declare their support for one candidate or another. Many people we spoke to said they had work or other commitments that would prevent them from attending.

Toward the end of our route, at the second-to-last door we knocked, Amy answered the door. We were looking for a different voter at that address, but she said it was her sister-in-law, who hadn’t lived there in years. When we knocked, her dogs barked and woke her child from a nap. We apologized, but she was happy to see us and interested in talking about our candidate.

“I don’t know all of the issues up and down,” she said, “but I’m a definite supporter.”

Amy was a veteran, and she was hopeful about the kinds of changes our candidate could bring about. I asked her if she planned to caucus the next day. She was surprised that it was happening so soon, and she said she wouldn’t be able to make it because of her kids.

“You can take children to the caucus,” I said.

But she said it was during dinnertime and would be a hassle.

During canvassing training, volunteers are instructed to make the conversation as personal as possible. Before leaving, though, it is important to make a definite ask for support in the caucus. Even though it can be hard, it is important to let people know that they are being counted on. I looked at Amy and the bright blond boy hanging at her waist. She had been eager to talk about the issues and the political direction of the country at length, but making her voice count was just out of reach. I handed her a flyer with her caucus information on it and weakly asked her to reconsider.

We talked to others, some Republicans and some with plans to caucus for other Democrats. Occasionally they seemed reticent, like we might hurl arguments or insults once we found out they didn’t support our candidate. There wasn’t the time or appetite for that, though. We had doors to knock and they had snow to plow. We wished them well, and they did the same.

On the long bus ride home, I couldn’t help but think of Amy as my great failure of the day. Maybe she would caucus after all, but probably not. Should I have pushed her a little harder? Could it possibly have made a difference? Maybe the best scenario we could hope for was that she realized some other people felt strongly in the same ways she did, and, even though it can be nerve-wracking, it’s not so impossible to talk about it.

Featured image: Shutterstock

In a Word: What Is a Caucus Anyway?

Managing editor and logophile Andy Hollandbeck reveals the sometimes surprising roots of common English words and phrases. Remember: Etymology tells us where a word comes from, but not what it means today.

While the Iowa Republican Caucus proceeded easily this week, with a basic secret ballot and no real challenger to the incumbent president, the Democratic Caucus didn’t go quite so smoothly. Not only do Democrats have more candidates to choose from, but they also rely on a more complicated caucus system that involves voters at more than 1,600 locations physically moving around the room to show their preferences.

And while many have been wondering about the process, the outcome, and the future viability of such a system, some of us spent our time wondering, “Where does the word caucus even come from anyway?” That turns out to be a more difficult question to answer than “Who won the Iowa Democratic Caucus?”

Why? Because no one really knows for sure. Merriam-Webster Dictionaries lists the etymology of caucus as “origin unknown.”

Although we don’t know the word’s precise origin or derivation, there are some things we definitely do know about the word, and there are theories beyond that. Here’s what we do know about the word caucus:

- It means “a closed meeting of a political party called together to choose candidates or decide policies,” and it can be used as a verb to mean “to gather for such a meeting.”

- It is not related to caucasian. (That word, which originally indicated “of or from the Caucasus Mountains,” took on its current meaning starting in 1795 through the work of German anthropologist Johann Friedrich Blumenbach.)

- It’s primarily an American word. In the U.K. (and other English-speaking countries with a parliamentary government), you won’t find references to political caucuses — though there was a “caucus-race” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, so the word must have meant something to the Victorians.

- It’s definitely not a Latinate word, which means its plural is caucuses. (Don’t even try to pull cauci on anyone.)

According to Merriam-Webster, John Adams reported in February 1763 of the upcoming meeting of “the Boston Caucus Club,” a group of city elders doing just what a caucus does today: choosing who will fill which positions in the local government. Why he chose that word is a something of a mystery.

The primary theory about the word’s origin is that it comes from the Algonquian word caucauasu. Algonquian is a Native American language group that was widespread in the North and Northeast and is the source of such common English words as moccasin, chipmunk, and Wyoming. In a Virgina dialect, caucauasu meant “elder, advisor.”

But while Adams’ Caucus Club was ostensibly a political gathering, it was also a social one. It’s possible that the word was derived from the Modern Greek kaukos “drinking cup,” something one might find in large quantities at a Caucus Club meeting.

It’s doubtful that Adams himself coined the word. Though his Caucus Club announcement is the word’s first appearance in print in a political context that we know of, it likely was had been circulating for some while in speech and in other documents that have been lost to time. And the longer it circulated, the more opportunity it had to evolve from its earliest iterations.

So we’re left only with theories. Unless new historical documents are uncovered pointing a clearer way to the beginning of this word’s history, we may never truly know where caucus came from.

Featured image: Shutterstock

10 Sorest Losers in American Politics

Americans like to think of themselves, and their representatives, as good sports. We admire winners who are humble, generous, and respectful of their opponents. We also admire losers who take defeat with stoic acceptance, good grace, and full responsibility.

But sometimes Americans don’t get the politicians they want. Winners rub their opponents’ face in the dirt, and losers either blame others for their loss or refuse to admit defeat altogether. Here is our list of the ten sorest losers in American politics.

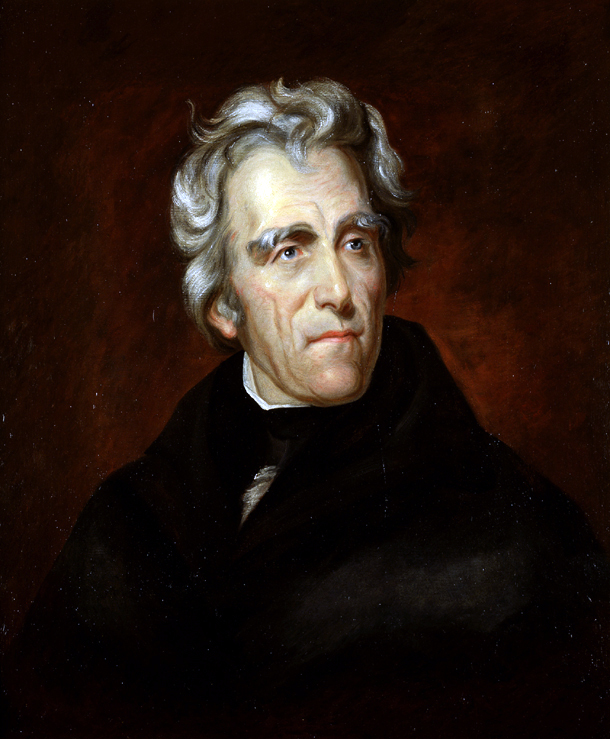

1. Andrew Jackson

In the 1824 presidential election, there were four candidates, all from the same party. (The opposing party had dissolved.) None of the candidates had enough electoral votes to meet the minimum number for a presidential win. Jackson had the most votes, but John Quincy Adams was close behind. In such cases, the contest was decided by the House of Representatives.

One of the other candidates, Henry Clay, allowed his congressional supporters to switch support to Adams, who then won the election. Once in the White House, Adams made Clay Secretary of State. Jackson was furious. He stormed back to Tennessee, telling everyone about the “corrupt bargain” that had robbed him of the White House. For the next four years, Jackson and his followers relentlessly attacked Adams and his administration. Jackson called Clay “the Judas of the west [who] has closed the contract and will receive the thirty pieces of silver.”

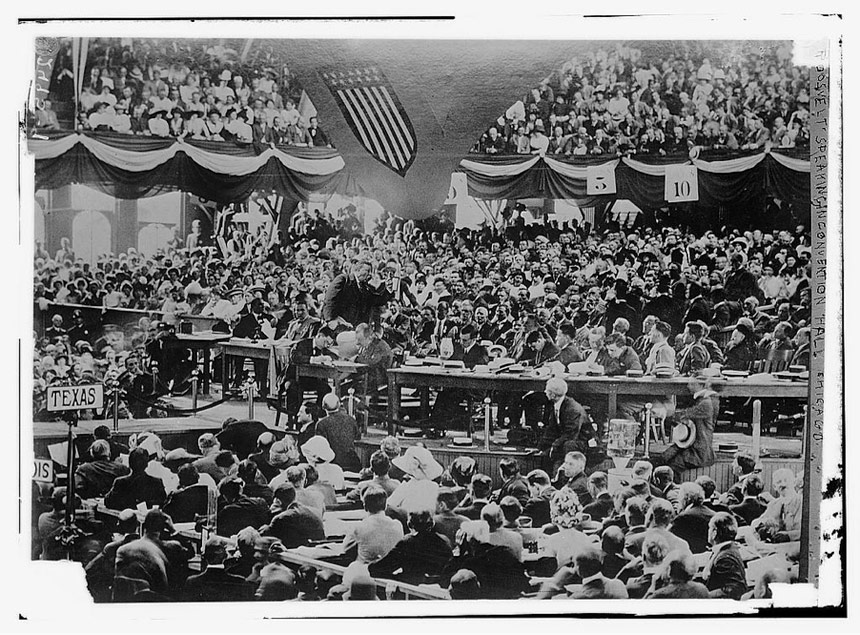

2. Teddy Roosevelt

In 1912, former President Theodore Roosevelt had fallen out with his protégé, President William Taft. He challenged Taft for the Republican primary for the coming election, confident the Republicans would turn to him. When they chose Taft instead, he stormed out of the convention and formed his own political party. Between them, Roosevelt and Taft split the Republican vote, allowing Democrat Woodrow Wilson to win.

3. Richard Nixon

After losing the presidency in 1960, Richard Nixon lost the governorship of California two years later. At a press conference following the announcement of his defeat, he addressed reporters with feigned good humor, saying, “For sixteen years…you’ve had a lot of fun… As I leave you I want you to know, just think how much you’ll be missing. You won’t have Nixon to kick around any more.” (Nixon was not just self-pitying, but absolutely wrong.)

Nixon’s speech following his 1962 loss in California. (Vimeo, University of Virginia’s Miller Center)

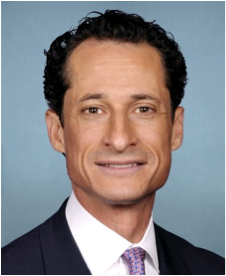

4. Anthony Weiner

Anthony Weiner lost his bid to become New York’s mayor in 2013, winning only 4.9% of the vote (not surprisingly). After making his concession speech, he left his campaign headquarters. As he stepped outside, reporters shouted questions at him. He made no reply as he made his way to a limousine. But once inside, Weiner responded to the reporters by raising a middle finger to them.

5. Gary Smith

In 2012, Gary Smith ran for the Republican nomination for Congress in New Mexico. When many of his nominating petition signatures were ruled invalid, he was dropped from the primary ballot. He responded by slashing the tires of the candidate who won, an act that was captured on security cameras. After posting bond, he was released, but picked up again when security cameras detected him lurking around the successful candidate’s home. He was sentenced to 30 months for “aggravated stalking.”

6. Marilyn Musgrave

Marilyn Musgrave lost re-election for a congressional district in Colorado in 2008. Rather than phone her congratulations to her opponent or give a gracious concession speech, she said nothing. She made no comment to the media, her supporters, or her staff. Six months later, according to Politico, she released a four-page letter declaring her intention to form a political action group and blaming her defeat on “extremists [who] finally spent enough money, spread enough lies, and fooled enough voters to defeat me.”

7. Ralph Nader

In 2008, Ralph Nader ran for president. He didn’t win, just as he hadn’t in 2000.

After acknowledging defeat, he said this about President-elect Barack Obama: “His choice, basically, is whether he’s going to be Uncle Sam for the people of this country or Uncle Tom for the giant corporations.” Nader was asked to clarify that comment by Fox News’ Shepherd Smith.

Smith: “I just wonder if in hindsight you wish you’d used a phrase other than ‘Uncle Tom?’”

Nader: (emphatically) “Not at all.”

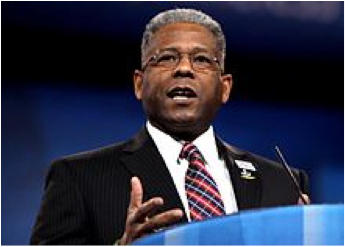

8. Allen West

After losing in 2012, Florida congressman Allen West contested the vote for two weeks before releasing the weakest possible concession to his opponent. Instead of acknowledging he lost, he said, “I am announcing that I will take no further action to contest the outcome of this election.” He wished his opponent luck, but gave his supporters reason not to view the victor as legitimate. There were still unexplained “inaccuracies in the results,” West said. He knew there were voting irregularities, but now was not the time to look into them. He said, “We uncovered a lot of things that now the people can continue to pursue.”

9. Joe Miller

In 2010, Lisa Murkowski lost Alaska’s GOP primary to Joe Miller, but then she won the election with an unprecedented write-in campaign, which required a painstaking hand-count of the ballots. As days passed, Miller refused to accept the results, despite party members and the state’s newspapers urging him to concede. Miller filed a federal lawsuit alleging violations by election officials, followed by a separate state court lawsuit. “Are we a nation,” he asked, “where some bureaucrat can, in the heat of the moment, make up basically the rules by which ballots are counted?” Because of Miller’s legal challenges, Murkowski wasn’t certified until December 30. That following June, Miller was required to pay the state of Alaska $18,000 in legal fees because a judge determined that the intent of Miller’s lawsuit was to win the election and not to uphold the state constitution, as he had claimed.

10. Chris McDaniel

In 2014, Mississippi State Senator Chris McDaniel pursued the Republican nomination for U.S. Senator, but lost in nasty, gloves-off race that featured nursing home break-ins, courthouse lock-ins, and “indecent things with animals.” McDaniel said the nomination had been compromised by “literally dozens” of voting irregularities. He offered a list of 15,000 illegal or questionable votes — a list that McDaniel’s attorney was surprised to see his own name on.

Let’s Hear It for the Gracious Losers

Lastly, there is the example of an exceptional concession speech, which was made by New York representative Joe Crowley after losing the Democratic primary to Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Having announced his defeat, Crowley picked up his guitar and, with a backup band, played Bruce Springsteen’s “Born to Run,” dedicating it to his opponent. Now that’s gracious.

https://twitter.com/twitter/statuses/1011824653671780352

Stuck in a Long Line to Vote? It Could Be Worse.

If you’re stuck in a long voting line today — hungry, tired, feet aching— consider what some voters in the rural West had to endure to vote in the 1946 election.

The Short Attention Span of Voters

—“Back to the Yoke,” Editorial, December 30, 1905

The other day an elephant, attached to a traveling show, got away, rushed through the streets of a town, trumpeting, burst in the glass front of a saloon and penetrated to the billiard-room, scattering several hundred men in wild alarm. There its keeper caught up with it and handed it a lump of sugar. It ate the sugar, became calm at once, and returned quietly with him. How like some elections, when the people go on a rampage for freedom, get a lump of sugar from the boss, forget all about their longing to be free, and return docilely to the yoke!