From Bloomers to Pantsuits: A Brief History of Women’s Dress Reform

Only within the last 70 years has it become socially acceptable for women to wear pants. Until the mid-1960s, the average American woman wouldn’t dare leave her house wearing dungarees. But as early as the mid-1800s, a few pioneering women had started quite literally making strides toward more practical women’s wear.

Dress Reform in the Mid-1800s

In the early 1800s, men’s and women’s fashion overlapped very little. Few women wore pants. For women, the purpose of clothing was not so much for function, but to make them look curvier, and it took women a significantly longer time to dress each day due to the number of layers they wore. The typical style included a dress or a long skirt with a blouse. Beneath the skirts were steel hoops and petticoats to make the skirt rounder. A corset also cinched the woman’s waist.

Because a typical woman’s life focused on her domestic duties, which in theory required less exertion than “man’s work,” the clothing a woman wore each day lacked functionality and made even the simplest tasks more difficult. Sitting down and bending over were hampered by the steel hoop, the layers beneath the dress, and the corset squeezing her middle.

Like other women, Elizabeth Smith Miller submitted to heavy and restrictive but fashionable caged dresses during the beginning of her life. But in 1851, while toiling in her garden in full dress, she got frustrated with “acceptable attire” and felt it a reasonable solution to change it. So she did.

She took inspiration from a trend she had seen in Europe, where women had taken to wearing “Turkish trousers” under their skirts — a trend not yet seen in America. Miller notably became one of the first women in the United States to brave in public the look of what would eventually be called bloomers under a knee-length skirt.

She wasn’t the only woman who felt trapped in her clothes. Miller’s cousin, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, shared her dissatisfaction and, seeing Miller’s bravery, decided to try out the same look.

Amelia Bloomer, Miller’s neighbor and friend, began promoting the new look in her newspaper, The Lily. At the time, her newspaper wasn’t known for being radical, but Bloomer hoped to spark some kind of change. She became a prominent voice of the women’s movement, using her platform to encourage other women to try out the new look themselves.

To promote this new style, Bloomer and other early feminists decided to take a particularly practical approach to bloomers. Instead of advertising comfort or gender equality or even freedom of movement, they publicized these pants as being better for women’s health: Petticoats, steel hoops, and corsets made healthful outdoor activities like hiking, swimming, and bike riding difficult for women, so they rarely participated in these activities. Bloomers, they argued, opened up these opportunities for exercise and fresh air. Occasionally, these arguments were reinforced with statements by doctors saying that the prevailing women’s fashion contributed to waves of illnesses that afflicted women.

This announcement from the August 1, 1857, issue of the Post points out that corsets and crinolines weren’t the best choices for a healthy lifestyle. Timour, also known as Tamerlane, was a 14th-century Asian conqueror who considered himself the political, if not biological, heir of Genghis Khan.

Though some younger women began wearing bloomers for bike riding, many Americans dismissed or discouraged the European trend. Miller and Bloomer were publicly shamed for their “radical dress.” In a document from the Elizabeth Smith Miller collection of the New York Public Library, she recalls enduring “much gaping curiosity and the harmless jeering of street boys.”

The movement did not escape the notice of The Saturday Evening Post, which published a short item on a gathering of the Dress Reform Association.

Miller had her own doubts and admitted to not feeling as beautiful as other women because her style didn’t accentuate the desired features of the time. However, she recalled inspiring words from her cousin, Elizabeth Cady Stanton: “The question is no longer, how do you look, but woman, how do you feel?” These words reminded her of how important this rebellion was to all women. She and other women believed women deserved more opportunities, starting with the simplest of things, like comfortable and functional clothes.

Unfortunately, outside of the bicycling trend, the movement gained little traction, and bloomers failed to become everyday wear as Miller and other feminist activists had hoped. However, the defeat was only temporary.

20th-Century Reform

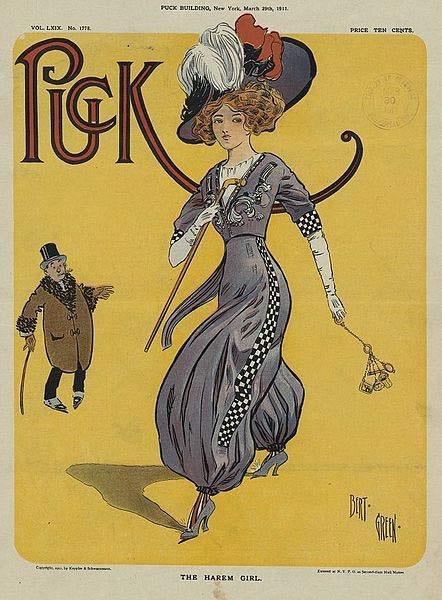

The fight for a woman’s right to wear pants arose again when French designer Paul Poiret’s “harem pant” hit the scene in 1909. More feminine than bloomers, these pants brought an alternative style that was both functional and flattering. Unlike bloomers, harem pants were made from silkier materials and embroidered and beaded with intricate detail.

These pants and other similarly designed trousers for women became especially popular with celebrities. In 1917, Vogue printed its first magazine with a woman wearing pants on the cover. Many more covers followed depicting women in different styles of pants.

Like bloomers, harem pants garnered a fair amount of backlash. These stylish pants were seen as too sexual for the average woman and remained in the confines of “celebrity fashion.” Like bloomers, the trend came and left, not quite making the jump to everyday wear.

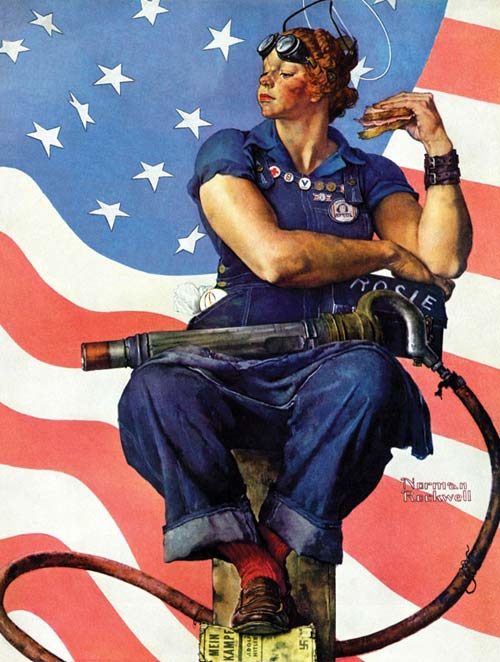

In the mid-1900s, World War II created a need for women to wear pants. As more than 16 million American soldiers shipped off to Europe and the South Pacific, businesses hired women to fill empty positions. The nature of many of these jobs made wearing dresses not only impractical but dangerous. Thus, thousands of working women found themselves wearing pants every day in support of the war effort.

But with little stable ground for this trend to build upon, it largely faded away again after the war ended. Pants no longer seemed necessary for domestic wives.

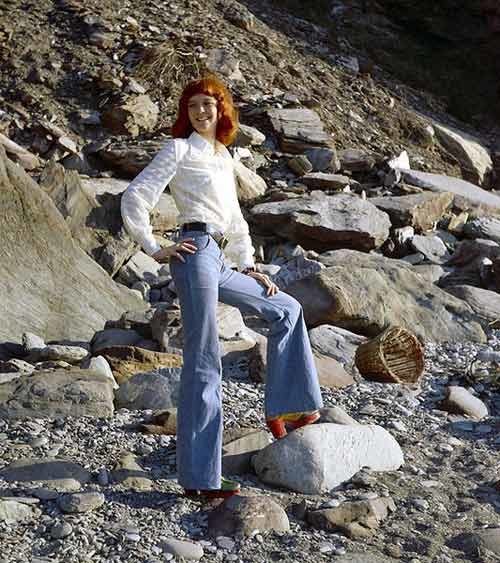

Lasting change finally came in the 1960s and early ’70s. For young people, rebellion was a way of life, and the perfect opportunity for pants to take center stage again. During the feminist movements of this time, fashion began to cross gender lines. The word unisex made its first appearance in print, and men and women alike sported T-shirts, ponchos, and wide-leg denim pants.

While women in pants became more common in public in the 1960s, acceptance at the highest levels of government was slow in coming. It would be another 30 years before women would be allowed to wear pants in the U.S. Senate. In the beginning of 1993, a number of female senators wore pantsuits in protest of an ancient rule of the official Senate dress code, and it was finally amended later that year.

Modern Fashion Statements

These days, Hillary Clinton is practically synonymous with pantsuits. During her 2016 presidential campaign, she wore them to practically every public event and was rarely seen in a skirt. Her attire became a symbol among her devotees, and even spurred the creation of “Pantsuit Nation,” a Facebook group of 3.9 million Clinton supporters.

Today, women from all different backgrounds wear trousers daily. This trend has become so popular that a new era of menswear-inspired fashion for women has become a high-demand look embraced by celebrities like former Spice Girl Victoria Beckham and singer Rihanna.

Women took hits for years for even wondering what it would be like to wear pants. Today, the simple wonder for many women is why they were not given such rights of function and fashion in the first place.

Women such as Miller, Bloomer, and Stanton pushed for change that led to the social acceptance that we take for granted today. As insignificant as the right for women to wear pants may seem now, it is a historical symbol of women’s perseverance over adversity and pursuit of equality.