Elvis on Ed Sullivan Show and the Clash of Sex and Race

Ed Sullivan changed his tune on “Elvis the Pelvis” after the up-and-coming star performed on The Steve Allen Show in 1956 and topped Sullivan’s ratings for the first time. Despite his earlier refusals (“I’ll not have him at any price — he’s not my cup of tea”), Sullivan booked Elvis for an unprecedented $50,000 for three appearances.

The first of those appearances was 61 years ago today, and it was the most-watched broadcast of the ’50s, summoning 82.6 percent of America’s television viewers.

Sullivan was recovering from a car accident the night of the broadcast, and Elvis was filming his first movie in Hollywood, so Brit Charles Laughton introduced Presley’s live Los Angeles performance. The CBS Television Studios set was decorated with abstract guitars, and Elvis appeared onstage in a plaid jacket, clearing his throat to giddy laughter from the hyper crowd. He performed “Don’t Be Cruel” and “Love Me Tender” and then — later in the show — Little Richard’s “Ready Teddy” and his own rendition of “Hound Dog.”

Like most of Elvis’ life, the first Ed Sullivan Show performance is shrouded in myth. Despite the availability of the original recording online, people still claim that Laughton introduced the singer as “Elvin” Presley and that the hip-swinger was recorded only from the waist up. In reality, Laughton clearly said “Elvis,” and a variety of camera shots were used. During “Hound Dog,” however, the show’s producer seemed to favor tighter angles of the performer.

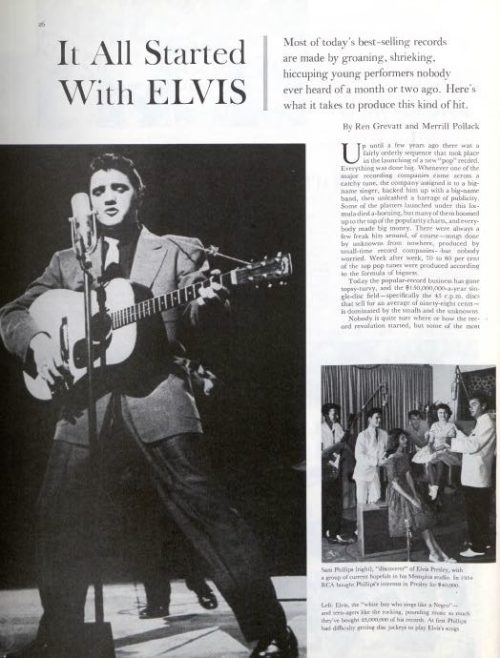

Three years later, the Saturday Evening Post article “It All Started with Elvis” proposed the homegrown celebrity acts and one-hit wonders coming into popularity were indebted to the success of “The King.” Writers Ren Grevatt and Merrill Pollack claim, “The ‘frantic’ sound is popular nowadays, and it applies to youngsters, like Presley, whose style is characterized by a frenzied, uninhibited, out-of-breath delivery. The ‘wail,’ the ‘moan,’ the ‘groan’ and the ‘shriek’ can, by extension, be considered legitimate categories.” In other words, Elvis brought sex to the stage.

At least, that was the supposed reasoning for the Nashville and St. Louis protests of his famed second appearance on the Ed Sullivan Show. Perhaps another reason for the disdain of Elvis’ performances is apparent in the 1959 Post article, in which Sam Phillips of Sun Recording Studios recalls his first experience recording young Elvis: “He was a white boy, but he was singing like a Negro.” The then-acceptable term for African-Americans is used several times in the article in reference to the music of rhythm-and-blues artists like Arthur Crudup and “Big Mama” Thornton — original performers of songs Presley would make famous, including “Hound Dog.” Although Elvis admittedly took considerable inspiration from country singers like Roy Acuff and Hank Snow, his dependence on black music and musicians is undeniable.

Phillips laments that Presley’s music was often rejected in the beginning due to its connection with African-American music: “The only place we got his records played at first was in the Negro sections of Chicago and Detroit and in California. Most of the Northern fellows were used to playing the smooth, sugary stuff, and in the South, even though Elvis was a hillbilly, the hillbilly disc jockeys refused to play him because they said he was singing ‘darky’ music.”

Whether this all amounts to Elvis bridging racial divides or profiting from another style is a subject of debate; it’s probably a bit of both.

In a 2007 New York Times article, Peter Guralnick discusses Presley’s refutation of his nickname “King of Rock ’n’ Roll,” citing Fats Domino as “one of my influences from way back.” Guralnick writes, “The larger point, of course, was that no one should be called king; surely the music, the American musical tradition that Elvis so strongly embraced, could stand on its own by now, after crossing all borders of race, class and even nationality.”

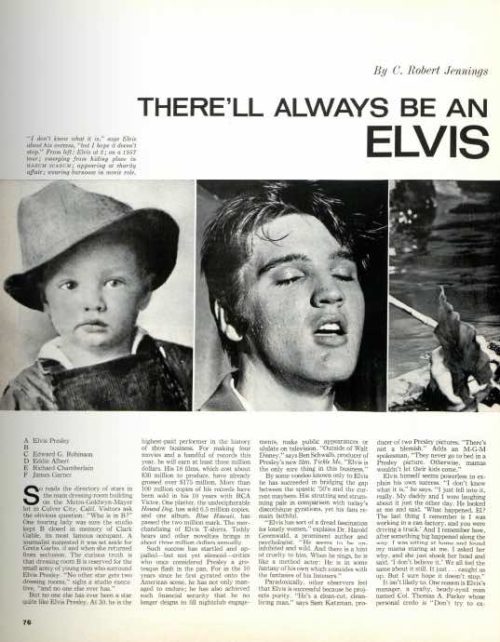

Despite a clear understanding of his roots, Presley himself was aloof about his own role as a sex symbol. The 1965 Post story “There’ll Always Be an Elvis” notes, “The criticisms stung both Elvis and his family. ‘I didn’t do no dirty body movements,’ he announced self-righteously. ‘When I sing, I just start jumping. If I stand still, I’m dead.’” The feigned innocence would be repeated by countless boy bands and pop divas several decades later, but Elvis very clearly understood the edge behind his performances as well as the reactions they would garner.

Perhaps author and psychologist Dr. Harold Greenwald put it best, saying “Elvis has sort of a dread fascination for lonely women. … He seems to be uninhibited and wild. And there is a hint of cruelty to him. When he sings, he is like a method actor: He is in some fantasy of his own which coincides with the fantasies of his listeners.”