The Middle Eastern Prince Who Tried to Change the Treaty of Versailles

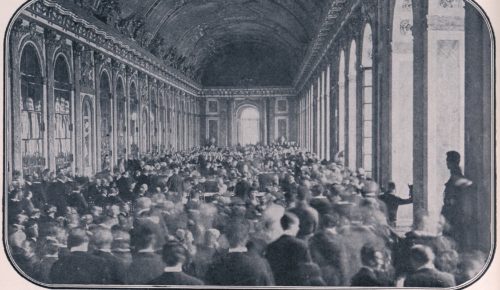

The Treaty of Versailles, the document that ended World War I, turns 100 years old on June 28. The Treaty is known for making Germany accountable for the losses of the war and for redrawing many national borders in Europe.

What is less well known about the Treaty is how one Prince from the Hejaz kingdom attended the Paris Peace Conference to try and reshape the Middle East.

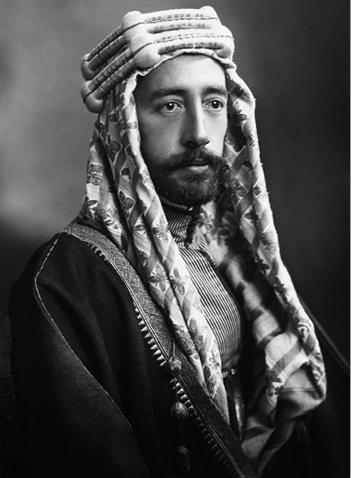

At the outset of the war British captain T.E. Lawrence (better known as Lawrence of Arabia) journeyed to the Middle East. He was seeking a ruler to lead the stalled Arab rebellion against the Ottoman Empire, with whom the British Empire was currently at war. The British wanted to weaken the Ottomans, and the Arabs resented being under their rule, so the task seemed straightforward. Lawrence found Emir (Prince) Feisal, the third son of the King of the Hejaz kingdom (modern-day Saudi Arabia) and knew he had found his leader. A charismatic man, Feisal was also believed to be a direct descendent of the prophet Mohammed, further encouraging the support of his followers. With the Emir in charge and the British supplying aid, the rebellion began in 1916. Arab troops reached the city of Damascus two years later.

This rebellion aided the British cause during the war, but as soon as the fighting stopped Arab leaders found themselves at odds with their former allies. In 1916, British and French diplomats had collaborated to divide the lands of the Ottoman Empire between their two nations. Known as the Sykes-Picot Agreement, these nations split the Arab region into zones of European influence. This agreement went against the promise of independence the Arab army had begun a rebellion to achieve.

At the end of the war Lawrence found himself called to Paris to participate in the Peace conference that would redefine the world after the war. Representatives from around the world gathered to create what would later be described in the June 26, 1922, issue of The Saturday Evening Post as “that recipe for ruin otherwise known as the Versailles Treaty.” Knowing that few politicians were concerned about the Middle East after the devastation in Europe, Lawrence encouraged Feisal to come with him and argue for Arab independence.

He did just that, though not without French resistance. Arab independence undermined French desires for control the Middle East, and the French delegation made several attempts to keep Faisal from the conference. Refusing to admit him as a British Delegate (the title Feisal had arrived under), the British government was forced to issue formal complaints. The British intervention allowed him entry, though only as a representative of the Hejaz region. Both Lawrence (who felt guilty for encouraging the rebellion with promises of independence) and Feisal worked hard to convince delegates that Arab independence was something worth fighting for.

Finally, Feisal stood before representatives from the British Empire, France, Italy, Japan, and the United States (including President Wilson) and argued (with Lawrence translating) that the Arab army had fought for the promise of independence after the war. Twenty thousand soldiers had lost their lives in a rebellion for a promise of freedom that was undermined by the Sykes-Picot agreement. When asked if Feisal meant to rule over one massive Arab nation, the Emir asserted that he did not mean to speak for the desires of all Arab peoples, he only aimed to give them the right to choose for themselves. The French, however, continued their attempted sabotage, bringing in their own Syrian representatives to degrade the Emir in front of the delegates.

At the end of the conference, delegates chose to honor the Sykes-Picot agreement over Feisal’s and Lawrence’s opposition. Europeans divided the Middle East into nations in a manner described by a February 11, 1922 Post article, titled Business Revival and Foreign Trade, as having “disturbed the currents of traffic which go back to the time of the children of Israel in Egypt, to the early days of Bagdad and Damascus, and to Marco Polo.” The French and British selected governments for the countries they had formed without consulting the governed, increasing tensions in those nations that later lead to violent coups and wars that are still fought today.

Emir Feisal was made king of British-controlled Iraq as consolation. Initially reluctant, the Emir agreed to rule (crowned in a ceremony with the British anthem “God Save the King” playing) and spent his time as King forming the national Identity of Iraq. He continued to advocate for pan-Arab nationalism until his mysterious death at age 48 in 1933. Feisal had been staying in Bern, Switzerland when he was found dead in his hotel room. The official cause of death was a heart attack, though an autopsy was never performed, and the King showed some signs of arsenic poisoning. Arab national sentiment led to the first of a series of violent coups 25 years later.

The Paris delegates’ actions at the Paris Peace Conference had far reaching consequences, though not many people connect the roots of Middle Eastern conflict to those men in Paris in 1919.

Featured Image: Faisal’s delegation at the Paris Peace Conference. (Wikimedia Commons)