What We Don’t Know about the World Beneath Our Feet

Find hints of it everywhere you go, evidence of an unseen world. Step out your front door and feel beneath your feet the thrum of subway tunnels and electric cables, mossy aqueducts and pneumatic tubes, all interweaving and overlapping like threads in a wild loom. At the end of a quiet street, find vapor streaming out of a ventilation grate, which may rise from a hidden tunnel where outcasts dwell in jerry-rigged shanties, or from a clandestine bunker with dense concrete walls, where the elite will flee to escape the end of days. On a long stroll through quiet pastureland, run your hands over a grassy mound that may conceal the tomb of an ancient tribal queen, or perhaps the buried fossil of a prehistoric beast with a long snaking spine. Hike down a shaded forest trail, where you cup your ear to the earth and hear the scuttle of ants excavating a buried metropolis, full of tiny whorled passageways. Trekking up in the foothills, you smell an earthy aroma emanating from a crack in the stone, the sign of a giant hidden cave, where the stony walls are graced with ancient charcoal paintings. And everywhere you go, beneath every step, you feel a quiver coming up from deep, deep below, where titanic bodies of stone shift and grind against one another, causing the earth to tremble and shudder.

If the surface of the earth were transparent, we’d spend days on our bellies, peering down into this marvelous layered terrain. But for us surface-dwellers, going about our lives in the sunlit world, the underground has always been invisible. Our word for the underworld, Hell, is rooted in the Proto-Indo-European kel–, for “conceal”; in ancient Greek, Hades translates to “the unseen one.” Today, we have newfangled devices — ground-penetrating radar and magnetometers — to help us visualize the underground, but even our sharpest images come out distant and foggy, leaving us like Dante, squinting into the depths: “so dark and deep and nebulous it was, / try as I might to force my sight below / I could not see the shape of anything.” In its obscurity, the underground is our planet’s most abstract landscape, always more metaphor than space. When we describe something as “underground” — an illicit economy, secret rave, undiscovered artist — we are typically describing not a place but a feeling: forbidden, unspoken, otherwise beyond the known and ordinary.

Our word for the underworld, Hell, is rooted in the Proto-Indo-European kel-, for “conceal.”

Geologists believe that more than half of the world’s caves are undiscovered, hermetic chambers down in the crust that will never be seen. The journey from where we now sit to the center of the Earth is equal to a trip from New York to Paris, and yet the planet’s core is a black box, a place whose existence we accept on faith. The deepest we’ve burrowed underground is the Kola borehole in the Russian Arctic, which reaches 7.6 miles deep — less than one half of one percent of the way to the center of the Earth. The underground is our ghost landscape, unfolding everywhere beneath our feet, always out of view.

But as a boy, I knew that the underworld was not always invisible — to certain people, it could be revealed. In my parents’ old edition of D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths, I read of Odysseus, Hercules, Orpheus, and other heroes who ventured down through craggy portals in the earth, crossed the river Styx on Charon’s ferry, gave the slip to three-headed Cerberus, and entered Hades, the land of shades. The one who most captivated me was Hermes, the messenger god, he of the winged helmet and sandals. Hermes was god of boundaries and thresholds, and the guide of the souls of the dead into Hades. (He bore the marvelous title of psychopomp, which means “soul conductor.”) While other gods and mortals obeyed the cosmic boundaries, he swooped openly between light and dark, above and below. Hermes — who would become the patron saint of my own underground excursions — was the one true subterranean explorer, who cut through darkness with clarity and grace, who saw the underworld and knew how to retrieve its buried wisdom.

The summer I turned 16, when my world felt as small and known as the tip of my finger, I discovered an abandoned train tunnel running beneath my neighborhood in Providence, Rhode Island. I’d heard about it first from a science teacher at school: a small, whiskery man named Otter, who knew every secret groove in every landscape in New England. The tunnel had once served a small cargo line, he’d told me, but that was years ago. Now it was a ruin: full of mud and garbage and stale air and who knew what else.

One afternoon, I found the entrance, which was concealed under a thicket of bushes behind a dentist’s office. It was wreathed in vines and had the date of its construction — 1908 — engraved in the concrete above its mouth. The city had sealed the entrance with a metal gate, but someone had sliced open a small passageway: Along with a few friends, I climbed underground, our flashlight beams crisscrossing in the dark. The mud sucked at our shoes and the air was boggy. On the ceiling were clusters of pearly nipplelike stalactites that dripped water down on our heads. Halfway through, we dared one another to switch off our lights. As the tunnel fell to perfect darkness, my friends whooped, testing the echo, but I held my breath and stood dead still, as though, if I moved, I might float right off the ground. That night at home, I pulled up an old map of Providence. I started with my finger where we’d entered the tunnel and moved to where it opened at the other end. I blinked: the tunnel passed almost directly beneath my house.

That summer, on days when no one else was around, I’d put on boots and go walking in the tunnel. I couldn’t have explained what drew me down, and I certainly never went with any particular mission. Underground, I’d look at the graffiti or kick around old bottles of malt liquor. Sometimes I’d turn off my light, just to see how long I could last in the dark before my nerves started to bristle.

At the end of that summer, following a heavy rainstorm, I had just climbed beyond the threshold of the tunnel when I heard an unexpected rumble coming from the darkness ahead. Alarmed, I started to turn back, but decided to keep walking, even as the sound grew. Deep in the tunnel, I found the source: a crack in the ceiling — a burst pipe, maybe, or a leak — from which water was pouring down in cascades. Directly beneath the falling water, I saw an overturned plastic beach pail. Then a paint bucket. Then, all at once, an enormous assembly of overturned containers — oil drums, beer cans, Tupperware, gas canisters, coffee tins — all in a giant cluster, arranged under mysterious circumstances by a person I’d never meet. The water drummed down on the vessels, sending up an echoing song, as I stood in the dark, nailed to the floor.

When we describe something as “underground” … we are typically describing not a place but a feeling.

Years passed, and I forgot about those underground walks. I left Providence, went to college, moved on. But my old connection to the tunnel never quite disappeared. Just as a seed silently takes root and ripens and matures down in the hidden earth before sprouting on the surface, my memories of the tunnel quietly germinated for years at the bottom of my mind.

I came to love the underground for its silence and for its echoes. I loved that even the briefest trip into a tunnel or a cave felt like an escape into a parallel reality, the way characters in childhood books vanish through portals into secret worlds. I loved that the underground offered romping Tom Sawyer-ish adventure, just as it opened confrontation with humankind’s most eternal and elemental fears. I loved telling stories about the underground — about relics discovered beneath city streets, or rituals conducted in the depths of caves — and the wonder they engendered in the eyes of my friends. Most of all, I was captivated by the dreamers, visionaries, and eccentrics that the underground attracted: people who’d heard a kind of subterranean siren song and given themselves to exploring, making art, or praying in the underground world.

Over the years, I convinced a research foundation, then various magazines, then a book publisher to give me funding to investigate these things, and I spent that money, and then some, exploring subterranean spaces in different parts of the world. For more than a decade, I climbed down into stony catacombs and derelict subway stations, sacred caves and nuclear bunkers. It began as a quest to understand my own preoccupation; but with each descent, as I became attuned to the deep resonances of the subterranean landscape, a more universal story emerged. I saw that we — all of us, the human species — have always felt a quiet pull from the underground, that we are connected to this realm as we are to our own shadow. From when our ancestors first told stories about the landscapes they inhabited, caves and other spaces beneath our feet have frightened and enchanted us, forged our nightmares and fantasies. Underground worlds, I discovered, run through our history like a secret thread: In ways subtle and profound, they have guided how we think about ourselves and given shape to our humanity.

We have lived among caves and underground hollows for as long as humans have existed, and for just as long, these spaces have evoked in us visceral and perplexing emotions. Evolutionary psychologists have suggested that even our most archaic ancestral relationships to landscapes never quite fade, that they become wired in our nervous system, manifest in unconscious instincts that continue to govern our behavior today.

We are aliens underground. Natural selection has designed us — in every way imaginable, from our metabolic needs, to the lattice-like anatomy of our eyes, to the deep structures of our brain — to stay on the surface, to not go underground. The “dark zone” of a cave — scientists’ name for the parts of a cave beyond the “twilight zone,” which is within the reach of diffuse light — is nature’s haunted house, repository of our deepest-rooted fears. It is home to snakes that twitch down from cave ceilings, spiders the size of Chihuahuas, scorpions with barbed tails — creatures we are evolutionarily hard-wired to fear, because they so often killed our ancestors. Up until about 15,000 years ago — which is to say, for all but the last eyeblink of our species’ existence — every time we came upon a cave mouth, we braced ourselves for a man-eating monster to lunge out of the darkness. Even today, when we peer underground, we feel the flickering dread of predators crouching in the dark.

The feeling of enclosure, too, leaves us unhinged. To be trapped in an underground chamber, our limbs restricted, cut off from light, with dwindling oxygen, may be the emperor of all nightmares. Edgar Allan Poe, the poet laureate of claustrophobia, wrote of subterranean enclosure: “No event is so terribly well adapted to inspire the supremeness of bodily and of mental distress. … The unendurable oppression of the lungs — the stifling fumes from the damp earth — the clinging to the death garments — the rigid embrace of the narrow house — the blackness of the absolute Night — the silence like a sea that overwhelms … ” Down in any underground hollow, we feel, if not a full tempest of panic, a reflexive tingle of not-quite-rightness, as we imagine ceilings and walls closing in on us.

Ultimately, it’s death we fear most: All of our aversions to the dark zone coil together in the dread of our own mortality. Our species has been burying our dead in the dark zones of caves since at least 100,000 years ago. Each time we cross a cave threshold, we feel a reflexive premonition of our eventual death — which is to say, we brush up against the one thing natural selection has designed us to avoid.

And yet, when we crouch at the edge of the underground, we do descend. Virtually every accessible cave on the planet contains the footprints of our ancestors: people who clambered down through rocky apertures in the earth, lighting their way through the gloom with pine torches or tallow lamps. Archaeologists have belly-crawled through muddy passageways in the caves of France, swum down long subterranean rivers in Belize, and trekked for miles inside the limestone caves of Kentucky: everywhere, they have found the fossilized footprints of ancient people, who made mysterious visits to the dark zone. The dark-zone journey may well be humankind’s oldest continuous cultural practice, with archaeological evidence going back hundreds of thousands of years, before our species even existed. No single tradition, writes the mythologist Evans Lansing-Smith, “brings us all together as human beings more than the descent to the underworld.”

To become conscious of the spaces beneath our feet is to feel the world unfold. Our connection to the underground cracks a door into the most inscrutable chambers of the human imagination. We go down to see what is unseen, unseeable — we go in search of illumination that can be found only in the dark.

Will Hunt’s writing, photography, and audio storytelling have appeared in The Economist, The Paris Review Daily, Discover, and Outside, among other places. Underground is his first book.

From the book Underground: A Human History of the Worlds Beneath Our Feet by Will Hunt, Copyright © 2018 by Will Hunt. Published by Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

The Republican Who Brought Environmentalism to the White House

In early 1970, President Nixon directed a message to Congress, outlining his plans for executive orders and calling for legislation to curb pollution and conserve America’s natural splendor. “Like those in the last century who tilled a plot of land to exhaustion and then moved on to another, we in this century have too casually and too long abused our natural environment,” he began.

Later that year, Nixon established the Environmental Protection Agency and supported the Clean Air Act. The president hadn’t campaigned on environmental issues — and his advisors attested that they weren’t a personal priority for him — but environmentalism had leapt in popularity for Americans in the late ’60s, when the disastrous externalities of the postwar boom were being thrust into public consciousness.

Although Nixon would eventually fall to the Watergate scandal — and tarnish any presidential legacy he might have had — his environmental legacy continued, thanks to one man. In 1973, Nixon appointed Russell Train to head the EPA. As a Republican administrator, Train centered the environment in American politics in an era when talk of conservation and regulation was bipartisan.

Today is the 100th anniversary of Russell Train’s birth.

After graduating from law school in 1948, Train began a career as a government tax attorney. He took two trips to Africa and found a new calling in environmental protection, thereafter co-founding the African Wildlife Leadership Foundation and soon taking leadership in the World Wildlife Fund. In 1965, he quit the U.S. Tax Court to dedicate his career to conservation.

When Nixon was approaching the presidency, his advisors picked Train to head a task force on the environment. As Train wrote in his memoir, Politics, Pollution, and Pandas, “The Nixon people made no effort to dictate or even suggest members, and I saw to it that the task force makeup was bipartisan.” The task force issued a report, claiming “environmental quality is a unifying goal that cuts across racial and economic lines, across political and social boundaries. It is a goal that provides a new perspective to many national problems and can give a new direction to national policy.”

At Train’s urgent recommendation, in 1970, Nixon signed the National Environmental Policy Act into law. The bill required reports on large projects under federal purview, and it proved to give unprecedented power to environmental groups when the courts began interpreting it as law. NEPA also established the President’s Council on Environmental Quality, of which Train became the first chair.

In the coming years, the Clean Air Act and Water Pollution Control Act Amendments passed as well. Train was a U.S. delegate to the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in 1972, the first such global summit, and he led the charge on the Coastal Zone Management Act as well as efforts to protect the Everglades. Ironically, as Nixon began to tire of environmental policy, privately, he also created the EPA, his broadest and most effectual environmental action. He placed Train as administrator — perhaps to get him out of the White House — in the wake of the Watergate scandal. Nixon was soon out, but Train remained in his position until 1977. In the EPA, he banned toxic agriculture chemicals and led in the approval of catalytic converters in compliance with the Clean Air Act.

In his memoir, Train sharply criticized George W. Bush and the president’s seeming rejection of Train’s legacy. In an interview in American Forests in 2006, Train gave a call for a return to his bipartisan environmentalism: “Overall, we need a brand new political climate that recognizes the environment is a key area of vital importance to this country today and in the future. It is of vital concern internationally and domestically. And we need a President who recognizes that and gives it full support. That’s what we need.”

Train was broadly supported by environmentalists during his tenure in government, including David Brower, the legendary head of the Sierra Club. In an interview in 1969, Train told John McPhee, “Thank God for Dave Brower. He makes it so easy for the rest of us to be reasonable.” Years later, Brower responded during a lecture in Kentucky, singing praises for Train‘s principled career: “Thank God for Russell Train — he makes it so easy for anyone to appear outrageous.”

Featured image: EPA

Preventing Food from Going to Waste

It’s a drizzly March morning in Nashville, and the sky looks like the garbage dump beneath it — a vast gray-brown morass. Against this backdrop, Georgann Parker appears like a Mad Max desperado. She’s wearing safety glasses and surgical gloves, tall rubber wellies over her jeans, a bright orange vest over her jacket, and a hard hat over her cropped gray-blonde hair. “We can be glad it’s not hot,” she says, smiling behind her respiration mask. Parker is uncannily upbeat for a woman about to perform a diagnostic exercise that’s technically called a waste audit but in Kroger inner circles is referred to as a dumpster dive. Parker is Kroger Company’s corporate chief of perishable donations, a role that occasionally involves ripping into hundreds of garbage bags to manually investigate their rotting contents.

Parker has come with two Kroger employees and two officials from Waste Management, the company that collects and dumps all of Kroger’s trash. They stand and watch as a compactor truck unloads on the ground in front of them. The trash mound has been generated over the previous six days by one of 2,800 Kroger supermarkets nationwide. Kroger’s stores serve 9 million individual American shoppers per day and 60 million American families per year, more than a third of the U.S. population. Each store produces many tons of trash a week — most of it perishable fruits, vegetables, meats, dairy, and deli products that have passed their prime or reached their sell-by dates but are still safe to eat.

It’s Parker’s job to help rescue Kroger’s sizable trove of safe-but-unsellable food across its many stores. She oversees the 120 division heads nationwide who manage the company’s food rescue operations. Annually Parker and her team capture about 75 million pounds of fresh meats, produce, and baked goods before they get thrown out, and donate them to local food banks and pantries. The number is big, but it’s a fraction of Kroger’s total fresh-foods waste stream. The company has pledged to donate more than ten times that amount as part of the Zero Hunger, Zero Waste campaign it launched in 2018. The goal is to eliminate food waste from its stores by 2025, and alleviate hunger in the communities surrounding these stores in the same time frame.

“Crazy-big” is how Parker describes the scope of Kroger’s goal, “and, yeah, a little daunting. The logistics of food rescue are very complex.” For a company as big as Kroger it means not only rescuing the food before it goes bad but coordinating the donations with tens of thousands of food banks and soup kitchens across the country.

Parker, who grew up in a town in Minnesota, is that rare person who manages to come off as both effusively and effortlessly friendly. In her colorful Midwestern patois, people are “folks,” soda is “pop,” a lot of something is “a crud-load,” and excitement is often expressed as a rhetorical question: “How cool is that?” In other words, she’s a gold mine of enthusiasm about things that many of us have trouble caring about — but should.

Whether because of her chipper disposition or because she’s seen more sobering circumstances in her professional past, Parker is unfazed by the disgusting conditions at the garbage dump. Odorous methane emanates up from the depths of the landfill below; dozens of overfed vultures circle heavily in the sky above as Parker and her team paw through the mountain of waste. They find bags of potatoes and cabbages that look perfectly fresh, heads of lettuce that look less so, heaps of boxed salads and spinach, serving trays of cut fruit, countless crates of cracked eggs, dozens of meal kits filled with prepped fresh ingredients for cooking shrimp scampi and chicken à la king, packages of sliced salami and cheese, cracked bottles of tomato sauce, dented tubs of icing and ice cream, and cans of Gravy Train dog food marked “Reclaim.”

Parker and her team separate the waste into categories, weighing and photographing the contents of each. Later, they’ll crunch the numbers and find that more than half — 52 percent — of the waste produced by the supermarket could have been donated, recycled, or composted. They will assemble the data into graphs and charts with crime-scene-esque photos. “You can see which departments in the store are doing their job of food rescue, and which are not,” Parker grumbles when we discuss the results. “A lot of this should have been given a second chance.”

Fifty-two million tons of food are sent to U.S. garbage dumps annually, and another 10 million are discarded or left to rot on farms, according to Darby Hoover, a waste researcher with the San Francisco office of the environmental group Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). Put another way, Americans waste enough food to fill a 90,000-seat stadium every day, and that’s about 25 percent more per capita than we were wasting in the 1970s. The average American throws out more than a pound of food a day — some 400 pounds per year each. Restaurants and retailers like Kroger are close behind, generating another third of it. The value of the food wasted in America each year has been estimated at between $162 billion and $218 billion.

Hoover sees the problem from an environmental angle. “Wasting food also means wasting all the water, energy, agricultural chemicals, labor, and other resources we put into growing, processing, packaging, distributing, washing, and refrigerating it,” she observes. The nonprofit group ReFed estimates that food waste consumes 21 percent of all freshwater, 19 percent of fertilizer, 18 percent of cropland, and 21 percent of landfill volume in the United States. Add to that the methane problem: only 5 percent of food waste in America gets composted into soil fertilizer, using a controlled process in which bacteria and heat decompose food scraps into rich plant nutrients. The other 95 percent of food waste goes to landfill and rots in an uncontrolled way, emitting methane, a potent greenhouse gas. “If food waste around the world was a country, it would rank third behind China and the U.S. in terms of greenhouse gas emissions,” says Hoover.

“Wasting food becomes an ethical problem when you consider that there’s about 40 million folks in this country living on poverty.”

To Georgann Parker, the problem is a social injustice: “Wasting food — especially healthy perishables — becomes an ethical problem when you consider that there’s about 40 million folks in this country living in poverty who don’t have reliable access to nutritious food.” Less than a third of the food we’re tossing would be enough to feed this underserved population.

Kroger’s Zero Hunger, Zero Waste campaign is also a bottom-line opportunity for the company, which has to pay increasingly steep “tipping fees” — the costs imposed by some state governments on the loads of waste that a company or institution dumps. Kroger can also collect millions of dollars in federal tax breaks annually for its food donations. Pressure to cut waste is also coming from Kroger’s investors. Nearly every major brand in food retail, including Publix, Walmart, Costco, Target, and Whole Foods, has introduced waste-reduction programs in the past five years. In a recent assessment of these programs by the Center for Biological Diversity, a nonprofit based in Tucson, Arizona, Kroger was the third-highest performer in the not-very-high-performing bunch — it scored a C on the overall grading scale.

To improve that, Kroger enlisted World Wildlife Fund (WWF), which conducts a large food-waste research program (on the grounds that agriculture is the world’s biggest threat to wildlife habitat), to help the company devise a strategy for food-waste prevention and donation. WWF encouraged the dumpster dives and other rigorous waste-stream analysis. “There’s a misconception that the answer to food waste is composting,” says Pete Pearson, WWF’s director of food-waste research. “The real emphasis — whether you’re a company, or a household, or a city — needs to be on prevention first, then rescue and donation, then composting as a last resort.”

“There isn’t any waste in nature. Anything that dies in nature becomes food for something else,” Darby Hoover tells me. “Humans have created waste as a concept, and we should be able to uncreate waste as a concept.”

Hoover recently conducted a two-year study exploring and comparing food-waste patterns in three U.S. cities — Denver, New York City, and Nashville. She found the foods most often dumped in the trash or poured down the drain included brewed coffee and coffee grounds, bananas, chicken, apples, bread, oranges, potatoes, and milk. Hoover noted the conspicuous absence of things like Doritos, Spam, and Twinkies on this list. “Food waste is riddled with unexpected contradictions, and one of them is that healthier diets tend to be the most wasteful diets,” she says. “Our current cultural obsession with eating fresh foods is a great thing from a health perspective, but not so great from a waste perspective.”

She also found that parents with young kids generated waste in their efforts, however hopeful and virtuous, to expose their kids to new flavors and healthy offerings — only to have the kids refuse to eat it. The upshot: food waste at the consumer level “is often tangled up with good intentions — and that makes it particularly tricky to solve,” Hoover observes.

“Here’s where we put the uglies,” says Georgann Parker as she walks me through the produce section of a Kroger supermarket outside of Indianapolis, Indiana — one of the largest stores in the chain. I’ve come to get a crash course in supermarket logistics and a glimpse into the company’s waste-prevention efforts. I’d never noticed these particular offerings in my local Kroger before. There, tucked into the side of an island bearing those iconic pyramids of supermarket fruit — perfect orbs of red, orange, green, and yellow — is a four-tiered shelf topped with a sign “Markdown! Beauty is only skin deep.” The shelves bear mostly empty straw baskets of gnarled bell peppers, arthritic-looking carrots, too-small cantaloupes, and cucumbers curved like pistols.

While fresh produce accounts for less than 15 percent of Kroger’s profits, it’s in the company’s interest to sell every last misshapen product. “We want everything that comes in the back door to go out the front, but of course it doesn’t,” says Parker.

Kroger introduced the “uglies” section into its stores in early 2017, around the time that activists and entrepreneurs were embracing cast-off produce, and the ugly produce program works in tandem with Kroger’s regular markdown programs. If meats don’t sell within a day of their sell-by dates, they get pulled from shelves, slapped with a “WooHoo! MARK-DOWN” sticker, and placed in the sale area of the meat section. If the discounted products still don’t sell, they’re supposed to be yanked the night before their sell-by date, scanned out of the system as a loss, and put in a backroom freezer for donation. A similar process is supposed to be followed for bakery items and dairy products. The company policy is to pull milk from the dairy case ten days before its expiration date, at which point it can be donated fresh, or frozen and then thawed for donation. “There’s no good reason any milk products sold in a Kroger store should ever be dumped,” says Parker.

Confusing sell-by labeling is another major barrier to waste prevention both in supermarkets and in homes. The dates printed on perishable products you buy are not federally regulated and do not represent any technical or standardized measure of food safety. The Food and Drug Administration, which has the power to regulate date labels, has chosen not to do so because no food-safety outbreak in the United States has ever been traced to a food being consumed past date. (They’ve been traced instead to certain pathogens that may have contaminated the food during processing; or to “temperature abuse,” like leaving raw chicken in a hot car; or to air exposure that encourages mold.) “You’re far more likely to get sick from something because it’s contaminated or gone unrefrigerated than because it’s past-date,” says Parker.

“Supermarkets have to juggle dozens of different date-labeling laws, and they lose about $1 billion a year from food that expires in theory — but not in reality — before it’s sold,” says Emily Broad Leib, director of the Food Policy Program at Harvard Law School. “Date label confusion harms consumers and food companies, and it wastes massive amounts of food.” Leib helped develop the Food Date Labeling Act, proposed federal legislation that would standardize labels to “best if used by,” a phrase indicating that a product may not be optimally fresh but is still safe to eat. The bill would also incentivize public schools and government institutions to make use of ugly fruits and veggies that never make it to market.

Parker says Kroger is throwing its lobbying weight behind this while also pushing for better food packaging. Materials scientists are now finally beginning to break new ground in food packaging and preservation techniques. The challenge in preserving freshness of perishable foods comes down to sealing out oxygen. It’s a seemingly benign gas, but when it penetrates food packaging it feeds mold growth and speeds the proliferation of microorganisms and enzymes. Parker tells me that researchers are developing oxygen-absorbing films that can be incorporated into either flexible or rigid packaging materials and reduce the oxygen concentration to within less than 0.01 percent — more than doubling shelf life. The problem is cost. Food manufacturers are still packaging bread in the same plastic bags and eggs in the same cardboard cartons they’ve been using for aeons because it’s cheap.

Kroger’s investment arm is funding start-ups that are developing new packaging technologies, but in the meantime, digital tools will get ever-better at tracking the life cycle of a product from conception to sale, which will go a long way to helping supermarkets reduce their excess inventory and donate far more of it.

It’s hard to overstate how much the global food system has changed in the last 30 years, and harder still to know how and how much it will change in the decades ahead.

Innovation and ignorance got us into the mess we’ve made of our food system, and innovation combined with good judgment can get us out of it.

From The Fate of Food: What We’ll Eat in a Bigger, Hotter, Smarter World by Amanda Little, published by Harmony Books, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Amanda Little.

This article is featured in the March/April 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock

What to Do About Plastic Bags

The cost of convenience is an island. Or, rather, many islands of floating plastics throughout the Pacific Ocean. Reports of dangerous and toxic ocean litter are a disturbing visual for our mounding plastics problem, but we seem to be at odds for a lasting solution. Taking action against free plastic bags can be a start.

Across the country, a patchwork of laws governs the use of plastic grocery bags. In some states — like California and, soon, New York — consumers must pay extra at checkout to use a more recyclable version of the plastic sack.

But in most states, we’re left to watch as the cashier triple-bags a Vidalia onion. Like an addictive narcotic — we just can’t quit.

Consider this an intervention.

A little more than a week ago, China’s National Development and Reform Commission and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment announced sweeping plans to curb single-use plastics throughout the country. The Chinese government says it will ban “nondegradable plastic bags” in cities by the end of this year and in rural areas by 2022. Twelve years ago, China made its first big move on plastic bag pollution, prohibiting retailers from distributing them for free and outright banning ultra-thin plastic bags.

In America, however, it seems many have accepted the ubiquitous plastic shopping bag as an inevitability. In fact, the journey to single-use plastic dependency in the U.S. has been a relatively short one guided by lobbyists and trade associations.

These urban tumbleweeds have only been drifting around the U.S. since 1979. In 1984, The New York Times covered the “battle of the grocery bags,” calling the paper-or-plastic question “a standoff between the future and the past, the familiar and the chic, the tastes of city dwellers and those of suburbanites.” That year, plastic grocery bags made up only 20 percent of the grocery bag market, but plastics consultants and Mobil representatives were confident that their thin polyethylene bags would soon take over. They were right.

After all, the strategy of the plastics industry since the ’50s has been to promote a throwaway lifestyle counter to the thriftiness of the war years.

Just a few decades after the Times predicted a plastic bag majority, Bangladesh became the first country in the world to pass a thin plastic bag ban. In 2007, San Francisco banned them, sparking municipalities all over the country to start looking at bans and plastic bag taxes.

The backlash from big plastic came swiftly. Groups like the (puzzlingly named) American Progressive Bag Alliance, a division of the Plastics Industry Association, backed efforts against the bans, like state laws prohibiting plastic bag bans and taxes in municipalities. Currently, 14 states have implemented such ban-bans.

The plastics industry argues that their film bags technically can be recycled (a prospect that amuses environmentalists and anyone else familiar with the recycling rates of even easily-recycled items), and they dismiss widespread environmentalist organizing as government overreach or regulation run amok. The problem is, as Naomi Oreskes pointed out to me a few months ago, if an industry or interest can sow confusion on a scientific issue, they can effectively thwart progress. If people aren’t sure that a plastic ban is the way to go, they will likely favor the status quo.

The discourse around what exactly should be done about plastic bags has taken several turns in the last decade or so. In the best possible scenario for plastics interests, it has become an endless left-versus-right debate instead of a critical discussion on how to move forward.

You might remember an episode of Planet Money last year that claimed banning plastic bags could actually be worse for the environment than not. NPR’s Greg Rosalsky cites data that sales in trash bags rise upon banning thin plastic bags. But, as others have pointed out, overall plastic use in the study Rosalsky cites was still a net negative (-70 percent). Even though consumers bought more trash bags than normal, everyone was still using less plastic.

Planet Money, and others, also used fatalist logic (and questionable data) to claim that alternatives to plastic bags have a larger carbon footprint, and therefore might not be worth pursuing. Of course, any reasonable strategy to combat climate change should aim higher than merely curbing the emissions of cotton bag production. The notion that we can’t implement bag bans and taxes without contributing to greenhouse gases is useless contrarianism.

Meanwhile, the frightening discovery of microplastics — and their prevalence in our air, soil, and water — has brought to light the urgency of curbing our rampant plastic use. Since plastic grocery bags are cheap, light, and plentiful, they’re an especially insidious addition to the environment. When they make their way into waterways, light and waves pound them into tiny pieces that end up in our stomachs.

In the Ocean Conservancy’s 2014 International Coastal Cleanup, plastic grocery bags were the seventh most common item found. That means there were six other more-common items, like straws, plastic bottle caps, and cigarette butts. Bans and taxes on disposable plastic bags shouldn’t be seen as unique regulations designed to burden consumers and stomp industry, but rather the salvo of a new age in which we discover, collectively, how to live without single-use plastics.

After all, it’s not such a tall order. We were doing it just a lifetime ago.

Featured image: Shutterstock; edited by Nicholas Gilmore

An American in Australia

In the Northern Territory of Australia, the world’s most fire prone land, there are rumors of flying arsonists. People have reported observing Black Kites and other birds of prey flying above the active front of a bushfire where unstable atmospheric conditions, dried vegetation, and high winds meet to produce the most dangerous conditions.

The raptors dart down toward crisp yellow grass, snatching and then dropping the lit stalks onto dry grass to propel the bushfire forward from its natural front. This hunting technique displaces living things, such as the spotted quoll, from their homes, making them easy prey

Two thousand miles south, in the Australian state of Victoria, people are reporting a class of even more unlikely arsonists: teenage girls.

On December 21st, the Saturday before Christmas, I was doing all of my shopping in a Myer department store in the capital city of Melbourne. The 2019 bushfire season in New South Wales and Victoria had been active for five months, since August, the Southern Hemisphere’s last month of winter.

A placid middle-aged man rang up the themed Lego sets I placed next to a purple and green placard that read “Please donate to the Bushfire Appeal.” These appeals, or donation drives, have become a ubiquitous part of shopping in Australia over the last few months. When I put gas in my car the attendant asks if I would like make the amount even to support the Country Fire Authority, or CFA, Victoria’s statewide network of volunteer and career firefighters. Gallons of milk have been renamed “Drought Relief Milk” (why do milk containers always have to bear bad news?), ensuring that even the most casual trip to the grocery store contains the potential for existential panic.

The cashier read me the total and asked if I would like to round up to the nearest dollar for the fires. I didn’t have the courage to refuse, although the more I learn about the current Liberal government’s mismanagement of the crisis I am led to conclude Australian citizens should not be cast upon at every exchange of money to subsidize this disaster like some horrific GoFundMe.

“You know about the fires, right?” The Myer cashier asks.

He was wearing a Santa hat with a golden bell on the end, and huddled on top of the box that contained the Jurassic Park Lego set I had purchased for my nephew. I told him my partner was a firefighter. When I met my partner twelve years ago, I was primed by years of t-shirted propaganda with silhouetted firefighters labelled as heroes, and I was enamored with the prospect of dating an Australian firefighter. Now, I obsessively update government fire maps and refuse to read articles about the dead firefighters.

“Oh, so he must really know about the fires then, how they started?” The cashier continued.

The bell on his hat rings as he talks.

“What do you mean?” I ask.

“Haven’t you heard?” He answers while he flings open a paper bag (plastic bags have been banned in Victoria).

“All these fires, they were started by teenage girls, so they can blame them on climate change.”

The Drought Relief Milk, banned plastic bags, and rumored roving gangs of teenaged arsonists are all the result of the prismatic shattering of the Australian psyche caused by the undeniable meeting of reality and delusion. Since the fires started in August, the country’s Prime Minister, Scott Morrison (or in true Aussie fashion, just ScoMo to both his supporters and critics) has invoked plastic usage and arsonists to deflect from critical questions about his party’s inadequate climate crisis policies. The 2019-2020 Bushfire season is the first reality test for ScoMo’s delusional policies.

Last year, 22 emergency services leaders sought a meeting with the Prime Minister to discuss perceived weaknesses in the Federal government’s disaster policies. ScoMo declined. Meanwhile, police and firefighting agencies have attributed just one percent of ignition of the fires to arsonists as ScoMo promises to launch a Royal Commission into the supposed arsonist problem.

The bushfires are the burning truth lashing at the delusions of climate denial still held by the Liberal party. ScoMo’s government and those who voted for it appear to be unable to let go of the fallacy that Australia has always faced fires of this magnitude, and therefore no significant policy change needs to occur. Instead, walls of milk gallons that sit on humming metal shelves are more capable of telling Australians the truth: we need a lasting relief from the effects of human caused climate change.

I evacuated from our small coastal town due to disastrous fire conditions. Weather forecasts predicted a preposterously high temperature of 114 degrees with winds travelling more than 40 miles per hour straight down the red center of the Australian outback. The days between Christmas and New Year’s Eve are normally a languid stretch of time revered by Australians, set aside for barbecues and watching “the cricket.” Instead, thousands of people were told to leave their homes. The lucky ones have somewhere to go while the rest stay filling bathtubs and garbage containers with water.

Those who stay will try to defend. The “stay and defend” strategy is controversial: In December, a father and son perished while trying to save their farm. They will not be the last father and son pair to lose their lives trying to defeat scorching radiant heat and flying embers this summer. I have always known what I will do when faced with the decision to leave or defend: get out. I’m from the Midwestern U.S., where the smell of fire is only associated with 4-H camp and bonfire parties. Now I try to mentally separate the instant nostalgia I feel as I step outside day after day and smell the whole country on fire.

There are worries that two fire complexes may cross the Victoria and New South Wales state boundary to become one monolithic fire from hell. I felt doom as I joined a caravan of people leaving to seek refuge. We passed whimsical signs depicting pastel seabirds stomping on cigarettes with speech bubbles proclaiming all Surf Coast beaches are smoke free as a monster cloud of smoke obscures the sun. Hardware stores throughout the Eastern coast of Australia sold out of P2 masks despite constant warnings from health officials that there is no way to filter smoke from the air.

Under normal conditions, fires in Australia are distinguishable events with clear beginnings and ends, such as the Ash Wednesday fires of 1983, or the Black Saturday fires of 2009.

The present fires have now been burning for almost six months.

The embers and active fronts have ashed 12 million acres of land, killed an estimated one billion animals and 29 people. ScoMo and other elected officials make daily media appearances pleading with us to keep the politics out of this, and look toward recovery. I reluctantly continue to donate to every bushfire appeal while purchasing a cup of coffee or buying a loaf of bread.

On December 30th, I was driving down the winding Great Ocean Road, a two-lane highway carved into the coast of the Southern Ocean, with my two dogs. I had not seen my partner in over a week. He had been stationed at remote airbases throughout rural Victoria waiting for streaks of dry lightning to ignite stretches of pale green stubby grass countryside that has not had significant rain in years. Sometimes he calls me from the base and I have to yell caged and coded questions about the fires. The hours he spends in a helicopter radioing to aircraft where to drop loads of water dyed red with phosphorus on the crackling heat are affecting his hearing. I ask him when he will be home, and what they are worried about today, but most of all I want to ask: what will be left?

Featured image: Bilpin, Australia on December 19, 2019, SS Studio Photography, Shutterstock

Shut Up and Compost

When I talk to hobbyist gardeners, evangelizing them on the gospel of composting, I’m always surprised to discover how many people seem to think it requires a supernatural ability or expensive materials.

Gardening itself is a much more intense commitment than composting. You can put as little or as much into composting as you’d like, and the result is an environmentally friendly fertilizer that completes the natural cycle of your home. Start composting today, and you could have some black gold in time for the first spring planting.

Begin saving food scraps from your kitchen. You can put them in a fancy container purchased just for this use, or you can throw them into any old bucket with a lid. Avoid putting meats, dairy, or excess salt or oil in your bin, but most everything else will break down nicely:

- Eggshells

- Coffee grounds (along with the filter)

- Vegetable cuttings

- Fruit rinds/apple cores

- Beer/wine

- Bread

- Loose leaf tea

When you’ve got a full kitchen bin, take it outside, toss it on the ground, and cover it with dead leaves and twigs and a layer of soil.

That’s it. That’s all you have to do to make nutrient-rich compost for your garden.

This method, called “cold composting,” can take several months or even years to completely break down your ingredients, but it will eventually work. There are several things you can do to speed up the process.

Composting works best when you have the perfect amounts of carbon, nitrogen, air, and water. Carbon comes from dead sticks, leaves, and paper. Nitrogen from food scraps, green plant scraps, and manure. Turning over a compost pile regularly introduces air. Water-wise, the rule of thumb is to keep it as wet as a wrung-out sponge as often as possible.

Composting is like a constant science experiment. It is difficult to mess it up royally, but the better you combine all of the elements, the faster you will have the good stuff.

A good ratio of carbon to nitrogen is 2:1. If you can satisfy this mixture, you should be able to practice “hot composting,” in which your compost pile heats up (usually to about 140° F) as microorganisms work to break down the materials.

As much as possible, try to break up or shred the materials you put into your compost pile. Sawdust and grass clippings work well because they are already broken down into a size more manageable for microorganisms. If you have chickens (or other vegetarian livestock), adding their manure (along with the bedding) onto a compost pile is a surefire way to heat it up.

For a backyard garden, two composting beds (about one cubic meter each) will be sufficient to handle your weeds, leaves, and leftovers. You can construct the walls with wood pallets lined with fine mesh screen. Just fill one over time, use a shovel to chop and mix it up, then leave it to cook while you fill the other. Turn the full pile inside out weekly, and it should resemble uniform topsoil in one to three months. For a smaller setup, consider buying a tumbling composter. I used one of these for years while living in small city duplexes, and I was able to compost all of my kitchen scraps to feed some gardening boxes.

In addition to feeding your garden with nutrients and microorganisms, compost improves the structure of your soil, increasing its capacity for water-retention and aeration. Just by taking a few small steps in the winter months, you can set yourself up for a successful garden all year.

Do:

- Allow compost containing manure to cure for a few weeks before adding it to the garden

- Consider a thermometer to monitor the temperature of your compost pile

- Try to keep food scraps in the center of the pile so you don’t attract pests

Don’t:

- Put non-compostable materials like plastic and metal into your pile

- Put materials in your compost that have been contaminated with harmful chemicals like cleaners or pesticide

- Put dog or cat feces into your compost

Featured image: Shutterstock

Why Do We Ignore the Dire Warnings of Scientists? An Interview with Naomi Oreskes

In 2004, Naomi Oreskes led an analysis of 928 papers on “global climate change” published in journals between 1993 and 2003, and she found that none of them disagreed with the consensus view that humans are causing global warming. Despite this finding, many Americans have been confused or doubtful about the scientific consensus of human-caused climate change over the years. Oreskes co-wrote Merchants of Doubt and The Collapse of Western Civilization, about the well-funded campaign against climate science and the catastrophic consequences of our own inaction, respectively. Her new book, Why Trust Science?, presents a case for the reliability of scientific consensus in a society where trust in institutions has fallen. She is a professor of the history of science and affiliated professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Harvard University.

The Saturday Evening Post: You talk about how our trust in science should be based less on the scientific method and more on the idea of consensus among scientists. Should we be teaching that in school?

Oreskes: I think — and there’s a large body of literature to support this — that the process of vetting claims is equally if not more important, because that’s, in a sense, where the epistemological rubber hits the road. Even if a scientist did follow the scientific method — had a hypothesis, did an experiment, the experiment worked out — there are so many possibilities for ways it could be wrong. Most egregiously, the scientist could be a fraud, but there are also a lot of less egregious things that could happen.

How do we know that a claim is legitimate? That’s where the rest of the scientific community comes in. A scientific claim is not accepted as scientific knowledge until it’s gone through this process of vetting by the rest of the community, which, in many cases, can be quite a lot of people. It’s that process that takes us to the point where we can say we’ve looked at a claim closely from a lot of different perspectives and we’re confident that it’s right.

Post: There’s this idea that “scientists are always changing their minds,” particularly when it comes to claims about diet and health. Where is the consensus on that?

Oreskes: This is a really important issue. First of all, the consensus on diet is much more robust than a lot of people think. I try not to beat up on journalists too much, but they have a lot of apologizing to do in this area. There has been so much irresponsible reporting on the issue of nutrition. We actually have a pretty clear idea about food. If you look at the typical American diet, we know the average American eats much too much meat, and that makes it more likely for people to have cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes, and colorectal cancer. There are a bunch of other things it may also contribute to, but those are the clearest ones. There is a huge body of evidence to support that claim. Now, we don’t have good evidence to say that you have to give up meat completely, but we do have very good evidence to say that if the average American were to eat much less meat they would, from a statistical standpoint, be much healthier. That’s almost unchallenged in the scientific community.

However, there are people who challenge it, and the media makes a big fuss about the people who do. Sadly, some of those people are supported by the meat industry. This is what we saw a few weeks ago. This encourages the exact sort of confusion you mentioned. If you’re an average person reading the newspaper, it seems like “last week red meat was bad, now it’s good. Who the heck knows, so I may as well just keep eating it.” In this case, I think we can say that’s exactly what the industry wanted. They want to create confusion — we know this from the history of tobacco — because confusion favors the status quo. So if you want people to keep eating a lot of red meat or to keep smoking or to keep driving big cars, one of the easiest ways to do that is to just confuse people.

Post: What would you say are some basic responsibilities of the media in reporting scientific stories?

Oreskes: The most important one, from my work, is knowing that science isn’t ever based on just one study. So, even if that study had been completely kashrut, and there’d been no industry bias, it would still behoove journalists to say “new study questions…” instead of “new study refutes conventional wisdom.” No one study can refute conventional wisdom because science just doesn’t work that way. Science is about bodies of evidence, bodies of data, ideally collected by many different people — to avoid bias and groupthink — ideally using different methods. Let’s say you had a study that was really methodologically robust and seemed to say “what we thought about X might not be right.” You should dig in and talk to other people in the field about how it was done and how likely it is that this study will really challenge our thinking. The vast majority of new studies don’t. The emphasis should be on that robust body of evidence.

Post: It feels as though there is a trend of distrust in science, given climate change skepticism and the anti-vaccine movement. Has trust in science waivered significantly lately, or does it only seem that way?

Oreskes: Mostly it only seems that way. We actually have quite good data from public opinion polls that show this, and, by and large, the vast majority of American people still trust in science. It is true that trust in experts of all kinds has declined since the 1960s, if you take the long view, but trust in science has actually fallen less than almost any other area, so trust in business, in government, in journalism — these have fallen dramatically since the ’60s. Relatively speaking, as a sector of society, scientists are doing well.

There are these conspicuous areas where we see the rejection of scientific findings by certain groups of people. It’s not a general distrust of science overall; it’s a rejection of findings in areas where people perceive that the findings of science conflict with their worldviews (political views, religious views, in some cases their economic interests). This is what sociologists call implicatory denial. We deny things because we don’t like their implications, and people do this in all aspects of their lives. What is special about our current period is the exploitation of implicatory denial. We now have organized networks of people who deliberately try to stoke doubt about climate change, evolutionary biology, and vaccination for political or economic reasons. This makes it difficult for scientists, because most of us aren’t interested in getting involved in a big, public, messy debate. But if you don’t get involved and explain to people what is going on, the American public will hear a lot of disinformation. When people hear something many times, they often will believe it’s true even if it’s completely false. Some of these groups know this.

Post: Do scientists have an obligation to act as their own “PR?”

Oreskes: I am sympathetic to scientists’ desire to do science, because that’s what they’re trained to do. A lot of scientists would prefer to be left alone to do their work. But I think we have to embrace a slightly different version of what constitutes “our work.” We have to accept that park of the work is explaining what we do to people.

Most science in America is funded by the American taxpayer. If we expect the taxpayers to pay for what we do, then we should also expect to spend some time explaining it, and explaining why it’s worthwhile and how the American people get their money’s worth many times over from scientific research. It’s in our own self-interest to do that. In addition, I think there’s a kind of social obligation, because if we don’t do that other people are quite happy to step in and create confusion. That leads to damaging results, like people failing to vaccinate their children and innocent children dying from preventable diseases.

Post: Should scientists be politicians?

Oreskes: By and large, no, because most scientists are not good politicians and most politicians are not good scientists. In general, no, scientists should be scientists. They should do the work for which they are trained and for which they have talent, but I think some adjustment of our conceptualization that were to incorporate a higher component of communication and outreach would be in order.

Post: As far as climate science is concerned, do you notice a trend of public figures accepting that we face a climate crisis while offering solutions that fail to address the scale of that crisis?

Oreskes: I think that’s correct. You can think about denial as not simply being an on-or-off switch, but as being a sort of spectrum. A lot of the work I’ve done is on hardcore denial, people who are completely rejecting scientific findings and generally doing it for motivated reasons. There is also what we could call “soft denial.” We’re seeing this now with politicians who will propose solutions that are nowhere near good enough or ambitious enough to actually address what’s going on. It’s not as pernicious as the hard denial that I’ve written about, but it is still damaging.

If you propose something really ambitious, you can be dismissed as being “unrealistic.” I think people who propose things that are inadequate are being really unrealistic too. There’s a way in which people like to pretend that they’re the grown-ups in the room. A lot of the time, that’s incredibly unrealistic, right? They’re pretending they’re being realistic, but they’re actually not because they’re not addressing the severity of the problem.

Featured image by Kayana Szymczak and Why Trust Science? © 2019 Princeton University Press. All Rights Reserved.

Katie Lee, the Kick-Ass Folk Singer and Nude Environmentalist

To this day, environmental activist groups continue to fight against the Glen Canyon Dam, a large concrete dam built on the Colorado River in the 1950s and ’60s in northern Arizona. The dam created Lake Powell, flooding Glen Canyon and drastically altering the ecosystem of the river. The resistance to the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s plan to dam the river was led by the Sierra Club and — perhaps less predictably — Katie Lee, a Hollywood actress and folk singer who had made a new life taking boat trips along the Colorado.

Lee would be 100 years old today (she died in 2017). The brassy, free-spirited performer and explorer was known for speaking her mind and doing it with curse words. She sang about the Colorado River (“My heart knows what the river knows/ I gotta go where the river goes”) and even about the cursed fates of government agency workers who would dam it (“For dam-builders come, but soon they’ll be gone/ To join the ghosts of old San Juan, the angry old ghosts of the river”).

In the burgeoning environmentalist movement, Katie Lee carved a space for kick-ass radicals to stand up — sometimes naked — to big money in the service of keeping America’s lands pristine.

As a newcomer to Hollywood in 1948, Lee had difficulty finding a niche for herself to get steady work. She was too old to be an ingénue and too young to be a character actress. She did work, though, playing small roles in film and television, and she recorded her first big album, Songs of Couch and Consultation, a folk pop record that satirized psychiatry. In the early ’50s, Lee received an offer to join some friends boating through the Grand Canyon, playing her guitar in the evenings. “I never went back to Hollywood,” she said, in the short documentary Kickass Katie Lee. “From then on, rivers were my lovers, and that’s what I did for the rest of my life.”

Though she loved the thrilling roughness of the Grand Canyon, Lee said she found her element in the calmer waters of Glen Canyon. Like an intimate Garden of Eden, Glen Canyon provided waterfalls, grottos, and more than one hundred side canyons for Lee and her fellow river runners to explore. They swam nude in its gorges by day and wrote folk songs around a campfire by night. The canyon was filled with Native American ruins and artifacts that hadn’t been touched for hundreds of years. Lee began accompanying tours with Mexican Hat Expeditions, bringing tourists up and down the Colorado.

“I remember being in the canyon on the ’57 trip, the day before President Eisenhower pushed the button and blasted the first blast off of the walls,” Lee said in a 1996 interview. “I heard the sound, and I remembered. It just brought me to my knees. I couldn’t handle it.” She noted a catch-22 of Glen Canyon’s secluded nature: the lack of crowds made it an idyllic spot to experience the West’s untouched natural beauty, but that also meant there were fewer people to speak out when the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation started work on a giant dam.

As early as 1954, Lee was aware of plans for a dam in the area. She wrote her senator, Barry Goldwater, appealing to his own interest in nature photography:

If you had not personally seen this country, Barry … lived in it, served it and let it serve you, I could understand your support of the Glen Canyon Dam as I would most politicians for their place in posterity. As it is I am completely bewildered and astounded. Can you have forgotten that it contains some of the most awesome and beautiful-beyond-description country in all the world?

Though Lee didn’t consider herself or her canyon companions politically-minded, they felt they had to do all they could to save their rocky refuge. She petitioned, rallied, and protested against the Glen Canyon Dam, wrote letters and songs, and gave interviews throughout her folk tours. By this time, Lee was being booked at clubs around the country, with help from her friend Burl Ives. She was zipping around in a ’55 T-Bird and playing with the likes of Harry Belafonte at progressively bigger venues and wider-reaching radio and television shows. In the midst of her hectic life in show business, Glen Canyon remained a safe haven.

In All My Rivers Are Gone, Lee’s 1998 memoir, she describes her calling to speak out against the Bureau of “Wreck the Nation”: “My river was about to be unjustly dammed … politically damned … I’d never had a cause before, but now there was a place, almost a person, that needed my help — a very valuable place that couldn’t speak for itself. I could be a voice for it.”

Sierra Club executive director David Brower called the Glen Canyon Dam “a power project pure and simple, built to provide a bank account for the Colorado River Storage Project.” In 1963, the dam was completed and closed up, flooding Lee’s beloved grottos and side canyons with hundreds of feet of water.

Over the next several decades, public opposition to the dam persisted. The proposed Bridge Canyon dam project, further down the Colorado River, was stalled and eventually defeated. In 1974, Lee wrote to Arizona representative Sam Steiger: “I thought that after the last defeat of dams in the Grand Canyon, any sane person would be more shamed than honored to go down in politics as an instigator of more cement plugs on the already over-dammed, evaporating, near-dead, Colorado River. But here you are!”

The recent lawsuit put forth by Save the Colorado and others asks the court to invalidate the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation’s 20-year plan for Glen Canyon Dam and to order a new one that accounts for the effects of climate change, preferably by recommending dam removal.

Groups like Save the Colorado and Glen Canyon Institute have yet to take down “the dinosaur of the dam world,” but their mission to spread word about the short-sightedness of dams resonates to people who know and care for the Colorado River. It’s the same message that Katie Lee sang in her 1964 album, Folk Songs of the Colorado River. “We drink to thee, oh Colorado/ Mighty river full of wonder,” she sang, the year after a cement wall buried her treasured canyon in a watery grave.

A decade before she died, Lee initiated a relationship with Northern Arizona University. She donated photographs, letters, manuscripts, and recordings to the school’s library. Last Friday, NAU began a two-year-long exhibit to honor Katie Lee’s legacy that is open to the public. It features her pictures and documents as well as Lee’s monkey wrench sculpture (a reference to Edward Abbey’s The Monkey Wrench Gang) and her front door, carved by her mother with images reflecting “Old Delores,” one of Katie’s favorite folk songs.

The exhibit, curated by student intern Britney Bibeault, features hundreds of photographs available online at NAU’s digital archives. They show Glen Canyon as Lee experienced it before it was filled in with water. In some, she and the other river rats are stark naked, embracing the vastness of a giant valley. The striking colors of sunlit geological formations and overexposed, lazy days on the river illustrate the bygone era of a canyon that has become impossible to explore — except through the memories of the people, like Katie Lee, who loved Glen Canyon like a good friend.

Featured image: Northern Arizona University, Cline Library, Katie Lee Collection

Saving Our Dying Waters — 50 Years Ago and Today

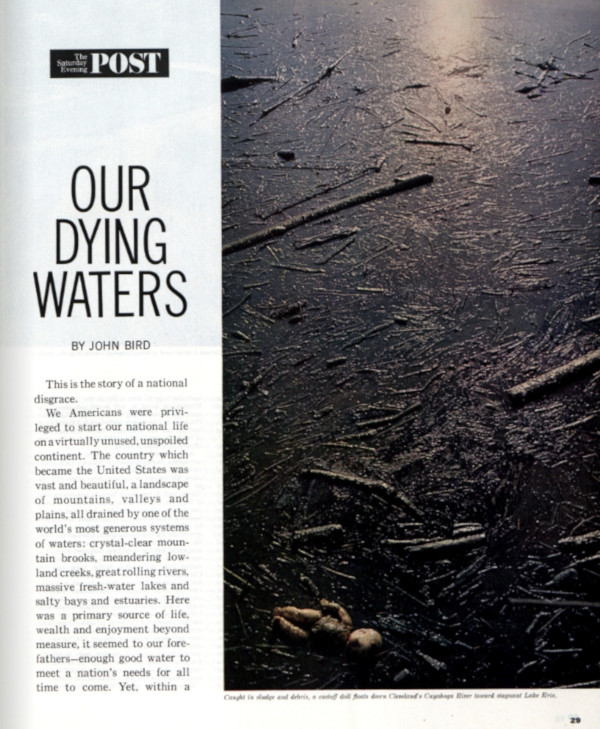

On a bright Sunday morning in June 1969, the Cuyahoga River caught fire. An oil slick atop the river caused by years of industrial waste burned with flames reaching over five stories. Three years earlier, on April 23, 1966, this magazine published an article by John Bird titled Our Dying Waters. Bird outlined the issue of America’s contaminated rivers and what needed to be done to fix them, claiming “the 21st century will be well underway before we are ready to cope with 20th-century pollution. We may choke on our own filth by then.” More than fifty years later, have we made any progress?

The outrage that followed the burning of the Cuyahoga spurred public support for political action, leading to the Clean Water Act (1972) and the creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (1970). Dying Waters emphasized the lack of regulation and outdated processing plants that heavily increased the amount of pollutants in water. Since the 1966 article, some progress has been made. The various acts that were passed increased testing of rivers and public water supplies and required closer monitoring of industrial waste. Regulated pesticides, less industrial water pollution, and more marine sanctuaries put an end to flammable rivers.

Unfortunately, contamination of rivers and reservoirs is not fully a thing of the past. An EPA report published in 2008 found that 46 percent of this nation’s rivers are in poor biological condition, leading to a loss of fishing and recreational facilities. This study reported that 24 percent of rivers have heightened levels of bacteria that “are indicators … of the possible presence of disease‐causing bacteria, viruses and protozoa.” Along with elevated phosphorous levels, mercury in fish, and loss of coastline wildlife, this report claims that “Our rivers and streams are under stress.”

The EPA introduced several methods of improving the biological condition of our rivers. The authors planned on investigating the source of the stressors, “including runoff from urban areas, agricultural practices and wastewater,” however no follow-up report has been published.

This sort of study did not exist in the time of Dying Waters, so it is unclear how the rivers of today compare to Bird’s. The major difference between now and 50 years ago is attention and regulation. Where there were no federal laws against pollution before the EPA’s creation in 1970, we have government agencies designed to test industrial waste. Where environmental disasters went unnoticed, we have contaminated drinking water making national headlines for weeks on end.

In his article Bird states that “We have taken it for granted that the water flowing from our faucets is free of disease, but we couldn’t be more wrong.” Today, roughly 25 percent of Americans drink from water supplies that violate the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974). Bird mentions the problems caused by salmonella infected waters in 1960. While there were no water-born salmonella outbreaks in 2015, 77 million people drank from water contaminated with coliform, nitrates, lead, copper, radionuclides, arsenic, and other contaminants. The 1960 residents that drank salmonella-contaminated water contracted high fever and nausea. Water quality in 2015 may have contributed to any number of ailments for the drinker from nausea and fever to cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Local and national attention surrounding Flint, Michigan, provides an excellent example of the nation’s ongoing water crisis. While the issue of lead contaminated water is relevant now (18 million people were drinking from lead-contaminated sources in 2015), lead was not even mentioned in Bird’s article. The true dangers of lead poisoning were not understood until the early 1970s.

The focus today has expanded to include water conservation as well as pollution. In 1966, the nation used 314 billion gallons of water per day. Now, although our population has increased by 68 percent, our water use has grown by only 2.5 percent to 322 billion gallons. While this is far better than the 1 trillion gallons Bird predicted the nation would need (the closest the country had come to that amount is using 435 billion gallons per day in 1980), it is still not a sustainable amount of water. While population continues to grow, the world’s water supply remains fixed. Statistics published by the United Nations predict that two thirds of the world will live in “water-stressed” countries by 2025 if current patterns of water-use prevail.

The facts are there: continuing to treat our water the way we have in the past puts millions of people at risk in addition to endangering aquatic environments. The article provides some hope for the future, emphasizing big picture ways of saving our dying water. Today there are many ways that everyday people can make a difference in our water crisis, we need only try. As Bird wrote half a century ago, “The only unknown is how long it will be before it’s too late.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

The Imprudent Promise of Plastics

In the exciting post-World War II years, the prophet of plastics rightly foresaw an industrial boom centered around these new durable and versatile materials.

Before buying a mountain to settle into in Vermont, Dr. Joseph Davidson had studied chemistry, served in World War I, and worked at Union Carbide’s K-25 plant in Tennessee, a secret factory that produced enriched uranium for the first atomic bomb. By 1950, he was president of Union Carbide’s chemicals division that held patents for laminated safety glass, vinyl compounds, and the trusty old plastic, Bakelite.

Arthur Baum wrote about the inventor and plastics dynamo in this magazine in 1950’s “The World Goes Plastic,” focusing on Davidson’s estate on Mount Equinox. High on the Vermont mountain, a vast property Davidson had steadily acquired throughout the ’40s, were his home and the Sky Line Inn. The inn exuded a “certain soul-disturbing significance,” according to Baum, for the omnipresence of plastics in its construction: “Thus the inn is a sort of challenging physical demonstration of the young plastic industry’s claim that its materials are already an improvement on nature.”

The praise heaped upon plastics — and the brilliant chemists behind them — was pervasive in the postwar years. The versatility of these thousands of new polymers presented a seemingly infinite set of possibilities for industry, medicine, and even a new American way of life. Innovators like Davidson seemed to have all the answers in the new plastic boom. All except one, of course: where will it all go once we’re finished with it?

The American “plastic age” began with Bakelite. First created in 1907 by Leo Baekeland, the “material of a thousand uses” came to be when the Belgian chemist found a way to control the reactions of phenol and formaldehyde to produce a moldable plastic. Bakelite could be used to make bowling balls, castanets, goggles, paper weights, and piano keys. A 1923 ad in The Saturday Evening Post boasted of the new plastic’s imperviousness to the elements that made it ideal “for your daughter’s jewelry and the ponderous dreadnaught.” Unlike old-news Celluloid, Bakelite held up to heat and electricity, making it ideal for electronics, weaponry, and everything in between. “It’s part of your everyday life!” a 1924 ad announced.

In 1939, Union Carbide bought the Bakelite Corporation. Chemists from across the complex international world of plastics were developing new polymers throughout the ’30s and ’40s, some of which would become staples of manufacturing. Nylon, polyethylene, and polystyrene were all perfected during this period. While Bakelite was a thermosetting plastic — meaning it was irreversibly hardened and shaped — these new thermoplastics could be pliable again when reheated.

The excitement around plastic’s endless prospects drove innovation for its own sake, as Jeffrey L. Meikle writes in American Plastic: A Cultural History: “The new generation of chemists, on the other hand, worked outward from chemical discoveries to the marketplace. When they found something of interest, they looked for ways to commercialize it. They were driven not so much by market demand as by the pressure of supply, an overabundance of chemical raw materials waiting to be exploited.”

The public wasn’t exactly clamoring for single-use plastics, but they were on their way nonetheless.

In 1950, Baum’s article stressed the plastic industry’s desire for a public educated in the subtleties of its products. Union Carbide and its competitors wanted consumers to know their acrylics from their alkyds just as they could tell cotton from linen. Manufacturer trade names for various plastics came and went. Some of them stuck, like DuPont’s “Nylon” and Dow’s “Saran,” and others, like American Cyanamid Company’s “Beetle Plastic,” were non-starters. At some point in the years following, the goal of branding polyethylene as some luxury material dropped off in lieu of a new one: teach the people how to throw it all away.

The Great Depression had instilled a sense of frugality and reuse into the populace. In the late ’40s and early ’50s, advertisements for plastic products focused on their design and durability. Dow’s “Styron” added “new color, beauty, and serviceability” to kitchenware and toys, and Monsanto’s “Lustrex Styrene” made “cheerful, convenient, and practical picnicwares” that were easy to clean. Disposability wasn’t yet a selling point, because it was more desirable to have a product that lasted.

That changed, however, in the ’50s. A now-infamous Life magazine spread in 1955 welcomed the new era of “Throwaway Living” with a photo of a family gleefully tossing their disposable napkins, plates, and utensils into the air, rejoicing in the reduced cleaning time. The move toward single-use plastics wasn’t a random occurrence. It was a calculated strategy by the industry in the interest of protecting its bottom line.

As environmental scientist Max Liboiron writes in “Modern Waste as Strategy,” “The truism that humans are inherently wasteful came into being at a particular time and place, by design.” That time and place, according to Liboiron, was the Society of the Plastics Industry’s New York conference in 1956. Lloyd Stouffer, editor of Modern Plastics, Inc., stood before the trade group and declared, “the future of plastics is in the trash can.” His statement was to be taken literally: if plastic manufacturers wanted to ensure a steady demand for their products, they needed to encourage a culture of disposability. The industry needed to convince consumers that plastic wasn’t too good to be thrown away.