Eric Liddell’s Greatest Race

Photos courtesy Heather Liddell Ingham, Patricia Liddell Russell, Maureen Liddell Moore, and The Eric Liddell Centre/Shutterstock.

Weihsien, Shandong

Province, China: 1944

He is crouching on the start line, which has been scratched out with a stick across the parched earth. His upper body is thrust slightly forward and his arms are bent at the elbow. His left leg is planted ahead of the right, the heels of both feet raised slightly in preparation for a springy launch.

Exactly two decades earlier, he had won his Olympic title in the hot, shallow bowl of Paris’ Colombes Stadium. Afterward, the crowd in the yellow-painted grandstands gave him the longest and loudest ovation of those Games. What inspired them was not only his roaring performance, but also the element of sacrificial romance wound into his personal story, which unfolded in front of them like the plot of some thunderous novel.

Now, trapped in a Japanese prisoner of war camp, the internees have teemed out of the low dormitories and the camp’s bell tower to line the route of the makeshift course to see Eric Liddell again. Even the guards in the watchtowers peer down eagerly at the scene.

Most of the world knows Liddell from the Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire. It frames him running across a screen, the composer Vangelis’ synthesized soundtrack accompanying every stride. The images, the music, the man, and what he achieved in the Olympics in 1924 are familiar to us because cinema made them so.

We know that Liddell, then a 22-year-old Edinburgh University student and already one of the fastest sprinters in the world, believed so strongly in the sanctity of the Sabbath that he sacrificed his chance to win the 100 meters. We know the early heats of that event were staged on a Sunday. We know that Liddell refused to run in them, leaving a gap that his British contemporary Harold Abrahams exploited. We know that Liddell resisted intense pressure — from the public, from his fellow Olympians, and from the British Olympic Association — to betray his conscience and change his mind about Sunday competition. We know that he entered the 400 meters, a distance he’d competed in only 10 times before. And we know that, against formidable odds and despite the predictions of gloomy naysayers, he won it with glorious ease.

In Paris, Liddell claimed his Olympic gold medal in a snow-white singlet, his country’s flag across his chest. Now, in China, he wears a shirt cut from patterned kitchen curtains, baggy khaki shorts, which are grubby and drop to the knee, and a pair of gray canvas “spikes,” almost identical to those he’d used during the Olympics.

Even though he is over 40 years old, practically bald, and pitifully thin, Liddell is the marquee attraction. Those who don’t run want to watch him. Those who do want to beat him.

As surreal as it seems, “Sports Days” such as this one are an established feature of the camp. For the internees, it is a way of forgetting — for a few hours at least — the reality of incarceration; a prisoner wistfully calls each of them “a speck of glitter amid the dull monotony.”

Until the Red Cross at last got food parcels to them in July, there were those who feared the slow death of starvation. Weight fell off everyone. Some lost 15 pounds or more, including Liddell. He dropped from 160 pounds to around 130. Morale sagged, a black depression ringing the camp as high as its walls.

While hunger stalked the camp, no one had the fuel or the inclination to run. So this race is a celebration, allowing the internees to express their relief at finally being fed.

Liddell shouldn’t be running in it.

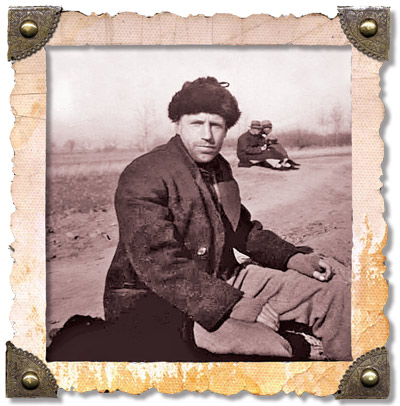

but slightly disheveled and unshaven, on his way

to Siaochang in late autumn 1937.

Photos courtesy Heather Liddell Ingham, Patricia Liddell Russell, Maureen Liddell Moore, and The Eric Liddell Centre/Shutterstock.

For months he’s felt weary and strangely disconnected. His walk has slowed. His speech has slowed too. He’s begun to do things ponderously and is sleeping only fitfully, the tiredness burrowing into his bones. He is stoop-shouldered. Mild dizzy spells cloud some of his days. Sometimes his vision is blurred. Though desperately sick, he casually dismisses his symptoms as “nothing to worry about,” blaming them on overwork.

Throughout the 18 months he’s already spent in Weihsien, Liddell has been a reassuring presence, always representing hope. He has toiled as if attempting to prove that perpetual motion is actually possible. He rises before dawn and labors until curfew at 10 p.m. Liddell is always doing something, and always doing it for others rather than for himself. He scrabbles for coal, which he carries in metal pails. He chops wood and totes bulky flour sacks. He cooks in the kitchens. He cleans and sweeps. He repairs whatever needs fixing. He teaches science to the children and teenagers of the camp and coaches them in sports too. He counsels and consoles the adults, who bring him their worries. Every Sunday he preaches in the church. Even when he works the hardest, Liddell still apologizes for not working hard enough.

The internees are so accustomed to his industriousness that no one pays much attention to it anymore; familiarity has allowed the camp to take both it and him a little for granted.

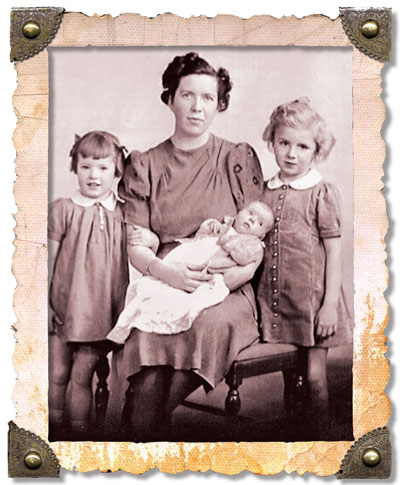

Since Liddell decades earlier first became public property — always walking in the arc light of fame — wherever he went and whatever he did or had once done was brightly illuminated. The sprinter whose locomotive speed inspired newspapers to call him “The Flying Scotsman.” The devout Christian who preached in congregational churches and meeting halls about scripture, temperance, morality, and Sunday observance. The Olympic champion who abandoned the track for the sake of his religious calling in China. The husband who booked boat passages for his pregnant wife and two infant daughters to enable them to escape the torment he was enduring in Weihsien. The father who had never met his third child, born without him at her bedside. The friend and colleague, so humbly modest, who treated everyone equally.

The internees assume nothing will harm such a good man, especially someone who is giving so much to them. And none of them has registered his deteriorating physical condition because he and everyone around him look too much alike to make his illness conspicuous.

Anyone else would find an excuse not to race. Liddell, however, doesn’t have it in him to back out. He is too conscientious. The camp expects him to compete, and he won’t let them down, however much the effort drains him and however shaky his legs feel. He is playing along with his role as Weihsien’s breezy optimist, a front concealing his distress. Every few weeks he merely slits a new notch-hole into the leather of his black belt and then pulls it tightly around his ever-shrinking waistline.

Liddell makes only one concession. Previously he has been scrupulously fair about leveling the field. He’s always started several yards behind the other runners, giving them an outside chance of beating him. This time there is no such handicap for him; that alone should alert everyone to the fact he is ailing.

Liddell says nothing about it. Instead, he takes his place, without pause or protest, in a pack of a dozen other runners, his eyes fixed on nothing but the narrow strip of land that constitutes the front straight.

The starter climbs onto an upturned packing crate, holding a white handkerchief aloft in his right hand. And then he barks out the three words Liddell has heard countless times in countless places:

Ready … Set … Go.

Present Day

He is waiting for me at the main gate on Guang-Wen Street. He is dressed smartly and formally: white shirt, dark tie, and an even darker suit, the lapels wide and well cut. He looks like someone about to make a speech or take a business meeting.

His blond hair is impeccably combed back, revealing a high widow’s peak. There’s the beginning of a smile on his slender lips, as if he knows a secret the rest of us don’t and is about to share it. Barely a wrinkle or a crease blemishes his pale skin, and his eyes are brightly alert. He is a handsome, eager fellow, still blazing with life.

On this warm spring morning, I am looking directly into Eric Liddell’s face.

He’s preserved in his absolute pomp, his photograph pressed onto a big square of metal. It is attached to an iron pole as tall as a lamppost. This is a communist homage to a Christian, a man China regards with paternal pride as its first Olympic champion. In Chinese eyes, he is a true son of their country; he belongs to no one else.

More than 70 years have passed since Liddell came here. He’s never gone home. He’s never grown old.

The place he knew as Weihsien is now called Weifang, the landscape unimaginably different.

When Liddell arrived in 1943, the locals, living as though time had stopped a century before, parked handheld barrows on whichever pitch suited them and bartered over homegrown vegetables, bolts of cloth, and tin pots and plates.

Photos courtesy Heather Liddell Ingham, Patricia Liddell Russell, Maureen Liddell Moore, and The Eric Liddell Centre/Shutterstock.

The camp once stood here. The Japanese called it a Civilian Assembly Center, a euphemism offering the flimsiest camouflage to the harsh truth. A United Nations of men, women, and children were prisoners alongside Liddell rather than comfy guests of Emperor Hirohito. There were Americans and Australians, South Americans and South Africans, Russians and Greeks, Dutch and Belgians and British, Scandinavians and Swiss and Filipinos. Among the nationalities there were disparate strata of society: merchant bankers, entrepreneurs, boardroom businessmen, solicitors, architects, teachers, and government officials. There were also drug addicts, alcoholics, prostitutes, and thieves, who coexisted beside monks and nuns and missionaries, such as Liddell.

Weihsien housed more than 2,100 internees during a period of two and a half years. At its terrible zenith, between 1,600 and 1,800 were shut into it at once.

A man’s labor can become his identity; Liddell testifies to that. Before internment, he worked in perilous outposts in China, dodging bullets and shells and always wary of the knife blade. After it, he dedicated himself to everyone around him, as though it were his responsibility alone to imbue the hardships and degradations with a proper purpose and make the long days bearable.

The short history of the camp emphasizes the impossibility of Liddell’s task. In the beginning, the camp was filthy and unsanitary, the pathways strewn with debris, and the living quarters squalid. The claustrophobic conditions brought predictable consequences. There were verbal squabbles, sometimes flaring into physical fights, over the meager portions at mealtimes and also the question of who was in front of whom in the line to receive them. There were disagreements, also frequently violent, over privacy and personal habits and hygiene as well as perceived idleness, selfishness, and pilfering.

Liddell was different. He overlooked the imperfections of character that beset even the best of us, doing so with a gentlemanly charm.

With infinite patience, he also gave special attention to the young, who affectionately called him “Uncle Eric.” He played chess with them. He built model boats for them. He fizzed with ideas, also arranging entertainments and sports, particularly softball and baseball, which were staged on a miniature diamond bare of grass.

Liddell became the camp’s conscience without ever being pious, sanctimonious, or judgmental. He forced his religion on no one. He didn’t expect others to share his beliefs, let alone live up to them. In his church sermons, and also during weekly scripture classes, Liddell didn’t preach grandiloquently. He did so conversationally, as if chatting over a picket fence, and those who heard him thought this gave his messages a solemn power that the louder, look-at-me sermonizers could never achieve. “You came away from his meetings as if you’d been given a dose of goodness,” said a member of the camp congregation.

In his own way, he proved that heroism in war exists beyond churned-up battlefields. His heroism was to be utterly forgiving in the most unforgiving of circumstances.

Liddell broke away from athletics at the peak of his flight. Sportsmen who reach the summit of their sport usually try to cling on there until their fingernails bleed. Well in advance of the Olympics, Liddell had talked of his intention to abdicate gracefully because his real calling was elsewhere. For most of us, that would be an easy vow to make before we became somebody — and an even easier one to break after the blandishments and the fancy trimmings of fame seduced us. Liddell never let it happen to him. He had promises to keep. That he kept them then and also subsequently is testament to exceptionally rare qualities in an exceptionally rare individual. Overnight, Liddell could have become one of the richest of “amateur” sportsmen. But he wouldn’t accept offers to write newspaper columns or make public speeches for cash. He wouldn’t say yes to prestigious teaching sinecures, refusing the benefits of a smart address and a high salary. He wouldn’t endorse products. He wouldn’t be flattered into business or banking either. He made only trivial concessions to his celebrity. He allowed his portrait to be painted. He let a gardener name a gladiolus in his honor at the Royal Horticultural Show. In everything else Liddell followed his conscience, choosing to do what was right because to do anything else, he felt, would sully the gift God had given him to run fast.

But what he did, and the way in which he inspired whoever watched him, doesn’t rank as his number-one achievement.

Surpassing his Olympic glory, and saying more about Liddell than any gold medal ever can, is the last race of his life — a race barely 1,500 people saw, making it almost a private event. A race he ought never to have attempted. A race no one registered as significant until much later.

Liddell began predictably, striding clear because he was aware of the need to establish an early lead. You could hear the stampede of thumping feet against the hard earth. You could see the short shadow each man cast and also the strain on their faces and in their eyes, the desperation of some who were already being left far behind.

Liddell was still ahead of them all at the halfway point of the second lap. This was the Olympian everyone knew — the frantic whirl of the arms, the high knee lift, the head back. The spectators, given another exhibition of it, waited for the climactic rush he always demonstrated. That assumption was wrong.

Worn down after his long months of illness, his legs let him down; he couldn’t find any “kick” in them. For once, throwing his head farther back wasn’t enough to give him that late spurt.

There was no spark, no extra burst of energy in him. His heart was willing. His body was not. Liddell came in second, several yards adrift.

This final race was Liddell’s best and unquestionably his bravest. Where his initial speed came from, and how he managed to sustain it for so long, is unfathomable. The courage he summoned to run at all is extraordinary, a testament to his will.

The passing years slowly assign context to things and place them in order of importance; we appreciate that only from the distance hindsight allows us. So it is with this race, a couple of minutes in a faraway corner of a faraway country that show the quintessential Liddell, a stricken man running because he felt it was the right thing to do. A man, moreover, who made no excuses for his defeat and got involved in no histrionics about it afterward. As the party-like atmosphere continued that day, he merely went back to his normal duties, still pretending there was nothing wrong with him.

Every morning in Weihsien, while the camp still slept, he lit a peanut oil lamp in the darkness and prayed for an hour. Every night, after studying the Bible, he prayed again. He did not discriminate. He prayed for everyone, even for his Japanese guards.

He died in the camp hospital in early 1945.

Whoever comes to this corner of China will always leave knowing that the full measure of the man is to be found here.

The place where his faith never broke under the immense weight it bore.

The place where his memory is imperishable.

The place where, even on the edge of death, the champion ran his last race.

From For the Glory: Eric Liddell’s Journey from Olympic Champion to Modern Martyr by Duncan Hamilton, Published by Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2016 by Duncan Hamilton.

Duncan Hamilton is an investigative journalist and award-winning sports writer whose recent book Immortal, a biography of footballer George Best, was named a best sports book of 2013 by both The Times and The Guardian. The author lives in West Yorkshire, U.K.