How to Be Neutral

Why does America find it so difficult to remain neutral?

Why do we seem impelled to take sides and get involved in global politics?

A century ago, as the U.S. watched Europe sinking in the First World War, President Woodrow Wilson asked Americans to be “neutral in fact, as well as in name. … We must be impartial in thought, as well as action, must put a curb upon our sentiments, as well as upon every transaction that might be construed as a preference.”

But when war returned to Europe 25 years later, President Roosevelt declared, “This Nation will remain a neutral nation, but I cannot ask that every American remain neutral in thought as well. Even a neutral has a right to take account of facts. Even a neutral cannot be asked to close his mind or his conscience.”

This was not neutrality, wrote Post contributor Demaree Bess, and he knew what he was talking about. For the previous two years he had been living in Switzerland. The small European republic had maintained its freedom for over a century while observing rigorous neutrality, which he defined as “the state of being friendly to two or more belligerents, or at least not taking the part of any.”

The Swiss, he wrote, couldn’t understand how Americans thought they were being neutral when they were encouraging their government “to line up with one set of European powers against another set, even before a war starts.” According to Bess, Americans thought simply declaring neutrality gave them the right “to take sides violently in every conflict which occurs in any part of the globe.”

The Swiss would stay out of the war, Bess wrote, because they would not fight for the things they believe in. The only cause for which the Swiss would take up weapons — which they were ready and prepared to do — was an invasion of their homeland. “They never even discuss the possibility of fighting for an abstract principle, such as collective security, or for any distant colony … or an ally in Eastern Europe. … They have only their own little country, which they spend all their time and attention cultivating. They are prepared and willing to fight for that country, if it is invaded.”

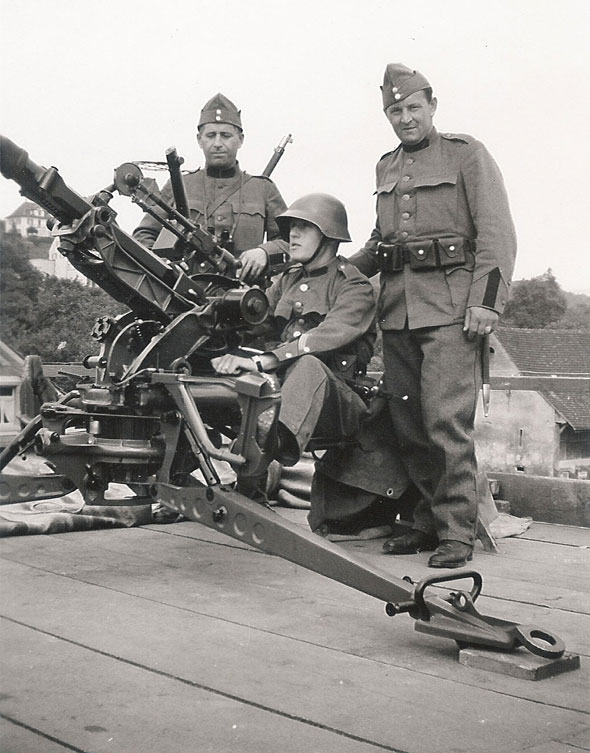

Between 1936 and 1939, the Swiss had spent $230 million to reorganize defenses. They modernized weaponry, especially antiaircraft defense and frontier fortifications. The government also increased the amount of training required of all Swiss citizens between 18 and 60 years of age. “This country of 4 million can put an army of 500,000 into the field within two days or less,” Bess wrote. When the Swiss Federal Council saw Europe sliding toward war, it mobilized the entire army. In just three days, its entire national force was ready.

Bess obviously admired the Swiss system, which, he reported, had created a “democracy united in its determination to preserve its democratic ideals as well as to keep its boundaries intact.” Reading his article, you get a sense that he thought the United States would be smart to adopt the Swiss model, and in his words “mind its own business.”

Could the U.S. have remained neutral, as its isolationists wanted? Probably not, in the long run. As much as its citizens might have wanted to stay out of the conflict, the country’s great wealth, spacious land, and open borders would have proved too tempting for the Axis, who would have found some pretext to seize American soil.

Japan was already anticipating an attack on American interests in the Pacific in 1939. Hitler, though, didn’t draw up concrete plans for conquering America, because he believed it was peopled by mongrel races incapable of defending themselves. He probably assumed that, after subjugating Europe and Russia, America’s manufacturing and agricultural wealth would simply fall into his lap.

Switzerland could make neutrality work because of several advantages America didn’t enjoy. First were its formidable mountainous borders. Admirable as its citizen army might have been, its effectiveness depended as much on the country’s alpine geography as its training and spirit. The Swiss army might have proved far less effective if it had to defend a nation as flat as Poland. Nazi Germany had, indeed, drawn up plans to invade Switzerland, but concluded that that conquering such a mountainous country wouldn’t be worth the cost.

Switzerland also benefitted from Nazi’s leniency toward the Swiss whom the Nazis considered essentially German. Hitler and his followers didn’t feel compelled to dominate the Swiss as they had the Czechs and Poles.

Besides, a small, wealthy neutral country next door offered many attractions to Nazi Germany. Switzerland provided an intelligence post where German agents could pick up Allied information. Also, several banks in Switzerland proved very helpful to Nazi officials who wanted to store their plunder beyond the reach of their own government. They found Swiss bankers more than happy to do business with them, even enabling them to store and trade stolen paintings.

Moreover, factories in neutral Switzerland, which weren’t being bombed by the Allies, could provide Germany with a steady supply of much needed steel and weapons. And, for a price, the Germans could use Switzerland’s transalpine railway to keep supplies flowing to their ally Italy.

But Bess couldn’t have known all this in 1939, when neutrality still seemed a workable response to the world war. The next seven months proved what a bad idea this policy was. One by one, other neutrals — Norway, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Holland — were seized by the Nazis, bringing the war closer to the shores of neutral America.

Step into 1939 with a peek at these pages from The Saturday Evening Post 75 years ago: