Remembering the 20th Century’s Leading Female Arctic Explorer

Sailing toward the west coast of Greenland in the war-torn summer of 1941, the Effie M. Morrissey navigated its way through a narrow fjord and anchored off the town of Julianehaab. The American ship appeared vulnerable and run-down next to the impressive U.S. Coast Guard vessels Bowdoin and Comanche.

It was a perilous time. Only eight weeks before, a British cargo vessel had been torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat off Cape Farewell just to the south. As newly minted members of the Greenland Patrol of the Atlantic Fleet, the Bowdoin and the Comanche were responsible for preventing German forces from establishing a base on Greenland and for providing vital support for the Allies.

As the Morrissey’s passengers disembarked, town residents gathered onshore. Commander Donald Macmillan of the Bowdoin hurried forward to greet the person in charge. Defying all expectations, the leader was no grizzled Navy man. Instead, a stately, well-coiffed California woman of a certain age clambered out of the rowboat and strode toward him.

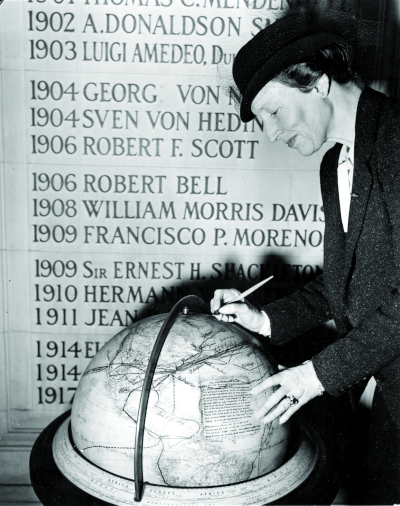

Louise Arner Boyd was the world’s leading female Arctic explorer and geographer. By that time, she had organized, financed, and led six maritime expeditions to East Greenland, Franz Josef Land, Jan Mayen Land, and Spitsbergen. She had been showered with honors by five countries, and her scientific accomplishments and daring exploits had earned her newspaper headlines and global renown. A month earlier, many journalists had covered the departure of the 1941 Louise A. Boyd Expedition to Greenland from Washington, D.C. But after the Morrissey weighed anchor, more than a few local residents wondered what this outspoken, unusual woman was doing in the company of high-ranking officers engaged in war matters.

“Far north, hidden behind grim barriers of pack ice, are lands that hold one spellbound.”

– Louise Arner Boyd

The answer to that question was a secret. Boyd, operating under the guise of her work as an explorer, was conducting a covert mission for the U.S. government, searching for possible military landing sites and investigating the improvement of radio communications. Even the captain and crew of her own ship were unaware of the expedition’s true goals.

Boyd’s extensive technical knowledge of Greenland and her work as a U.S. military consultant would make her an invaluable asset to the Allied war effort. But, for all her accomplishments and service to her country, she has largely been forgotten, and not just because historians preferred to consider the larger-than-life dramas of her male colleagues. Her focus on contributing to scientific journals rather than pandering to the sensationalistic whims of the reading public cost her some acclaim. And she had no direct descendants to carry on her legacy.

Her 1941 mission along the western coast of Greenland and eastern Arctic Canada was Boyd’s seventh and final expedition. As on her previous voyages, she pushed the boundaries of geographic knowledge and undertook hazardous journeys to dangerous places. “Far north, hidden behind grim barriers of pack ice, are lands that hold one spellbound,” she wrote in 1935’s The Fiord Region of East Greenland. “Gigantic imaginary gates, with hinges set in the horizon, seem to guard these lands. Slowly the gates swing open, and one enters another world where men are insignificant amid the awesome immensity of lonely mountains, fiords and glaciers.”

But her life had not always been like this. Born in 1887 to a California gold miner who struck it rich and a patrician mother from Rochester, Louise Arner Boyd was raised in a genteel mansion in San Rafael, California. As a child, she was enthralled by real-life tales of polar exploration, but grew up expecting to marry and have children. Like her mother, Boyd became a socialite and philanthropist active in community work.

But her life took unexpected turns. Her brothers died young; her parents did not survive into old age. By the time she was in her early 30s, she had lost her entire family and inherited a fortune. Unmarried and without children, she followed a dream to travel north.

Her first tourist cruise to the Arctic Ocean was so moving that she returned a few years later. This second voyage was also only a pleasure trip, but she chose Franz Josef Land as her destination — then as now, one of the most remote and unforgiving locations on Earth. Following her return to California, Boyd knew that her future was linked to the north. But it took a stroke of destiny to transform her into an explorer.

Boyd planned her first full expedition and arrived during the summer of 1928 in the far northern Norwegian city of Tromsø, prepared to set sail. She was shocked by the news that the iconic explorer Roald Amundsen — conqueror of the South Pole and the first person to successfully traverse the Northwest Passage — had vanished while on a flight to rescue another explorer. A desperate mission involving ships and airplanes from six European countries was launched to locate Amundsen and his French crew.

Boyd lost no time in putting the ship she had hired, as well as the provisions and services of its crew, at the disposal of the government in its rescue efforts. But there was a catch — Boyd demanded to go along. The Norwegian government eagerly accepted her offer, and she ended up an integral part of the Amundsen rescue expedition. Only the most experienced and high-ranking explorers, aviators, and generals had been chosen for this dangerous undertaking, and no allowances were made for a woman. Despite her lack of expertise and the skepticism of male expedition participants, Boyd assumed her responsibilities with vigor.

Tragically, Amundsen was never found, but by the end of that fateful summer, Boyd had won awards from the Norwegian and French governments for her courage and stamina. And she had discovered her purpose in life as an Arctic explorer.

From this point forward, she began living a double life. While at home in the United States, she was a gracious hostess, a generous benefactor, and a beloved member of California high society. While sailing on the high seas, she assumed a different, heroic identity.

How did one become an explorer? She had no formal education to draw on. She had left school in her teens, had limited outdoor expertise, and no family members remained to advise her. Instead, she implemented her charm and networking skills to identify individuals who could help her. She developed an unerring ability to choose exactly the right scientist for the job. Her expedition participants included geologist and famed mountaineer Noel Odell, who was the only survivor of the tragic British Mount Everest Expedition of 1924. She was also a remarkably fast learner who sought out experts in her fields of interest — including photographer Ansel Adams and California Academy of Sciences botanist Alice Eastwood — to teach her what she needed to know.

During the 1930s and ’40s, Boyd’s skills and abilities as an explorer grew. Unlike her male colleagues, she had no interest in conquering territories or being the “first.” Rather, as a self-taught geographer who was awarded the Cullum Geographical Medal in 1938 (only the second woman to earn it), Boyd focused on contributing to science.

She left extensive photographic documentation of Greenland currently used by glaciologists to track climate change in Greenlandic glaciers. She pioneered the use of cutting-edge technology, including the first deep-water recording echo-sounder and photogrammetrical equipment to conduct exploratory surveys in inaccessible places. She discovered a glacier in Greenland, a new underwater bank in the Norwegian Sea, and many new botanical species. More than 70 years later, data generated during her expeditions is still cited by contemporary scientists in the fields of geology, geomorphology, oceanography, and botany.

After the perilous 1941 mission to Greenland was a resounding success, the National Bureau of Standards commended Boyd for resolving critical radio transmission problems they had grappled with in the Arctic for decades. A certificate of appreciation from the Department of the Army extolled her “exemplary service as being highly beneficial to the cause of victory.”

For all this good work, she was not universally respected by her expedition participants. Initially, most academics were happy enough with her credentials and her generous offer to join the team, but once the expedition was underway, some of them ridiculed her and undermined her position as leader. University of Chicago geologist Harlen Bretz and Duke University plant ecologist H.J. Oosting wrote scathingly about her.

By the time the war was over, Louise Arner Boyd was nearly 60 years old; the 1941 trip was her last true expedition. In 1955, she would realize a dream by becoming one of the first women to be flown over the North Pole. And her polar work continued — through her active participation as an American Geographical Society Councilor, and as a member of the Society of Woman Geographers and the American Polar Society — until her death in 1972.

Today the name Louise Arner Boyd is only a dim memory. But it is one worth reviving.

This article is featured in the July/August 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Originally appeared at Zócalo Public Square.

Featured image: Louise Arner Boyd. Courtesy Joanna Kafarowski.

This article is featured in the July/August 2019 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.