Ben Franklin Used Fake News

It may seem like our political climate, in which politicians and journalists are accused of inventing phony stories, is unprecedented. Yet there are similarities to past events, and some of the perpetrators of early political chicanery may surprise you.

For example, in 1782, while still representing the United States in Paris, Benjamin Franklin printed a fake edition of an actual Boston newspaper, The Independent Chronicle. Amid the fictitious ads and articles, Franklin inserted a made-up story about the massive slaughter of white settlers on the frontiers of New York. Native Americans, in the service of the British forces, had collected 700 scalps from men, women, children, and even infants, Franklin lied.

When the news reached America, it was reprinted in papers throughout New England. The story helped stiffen American resistance to the British, who were now seen as using Indians to terrorize settlers. Released in Paris, the story also helped sway European opinion against England.

Franklin’s “fake news” was just the start of a long tradition in American politics.

As we noted in “Crude Language on the Campaign Trail,” presidential campaigns have often been marked by fabricated stories and synthetic scandals. Even after the race, the slander often continued.

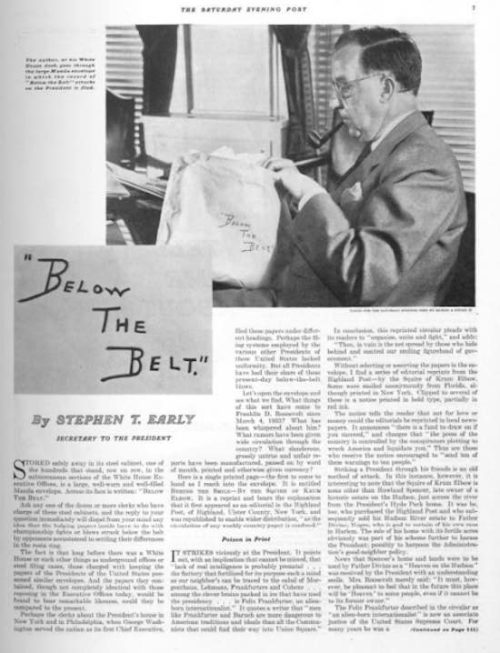

In 1939, Stephen T. Early, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secretary, shared several examples of disinformation campaigns directed against the president.

Roosevelt enjoyed broad support among voters, particularly in the early years of his presidency. But he remained a controversial leader for many Americans. Some of his opponents hoped to blacken his reputation with reports of corruption or dishonesty in the White House.

In a file he marked “Below the Belt,” Early gave examples of these fake news stories. Some hinted at sinister, international conspiracies implicating Roosevelt, a foreign-born Supreme Court justice, and labor leaders, among others. One story claimed President Roosevelt had prevented the capture and trial of the true kidnappers of the Lindbergh baby. The kidnappers, it argued, were protected by the president and were still kidnapping and murdering.

Early wondered, as many Americans do today, “just how gullible do these muckrakers think the American people are?”

Roosevelt, however, refused to be baited by these stories. When a publisher reported that the president had fallen into a coma, he offered to print a retraction if the White House issued a denial. All he got was silence. Roosevelt refused to reward him with more media attention.

Unfortunately, in our era of 24-hour information, ignoring even flagrant fake news doesn’t seem to be an option. What and whom are we to believe? In both the literal and figurative sense, we are left to our own devices.