A Modern Master of Western Art

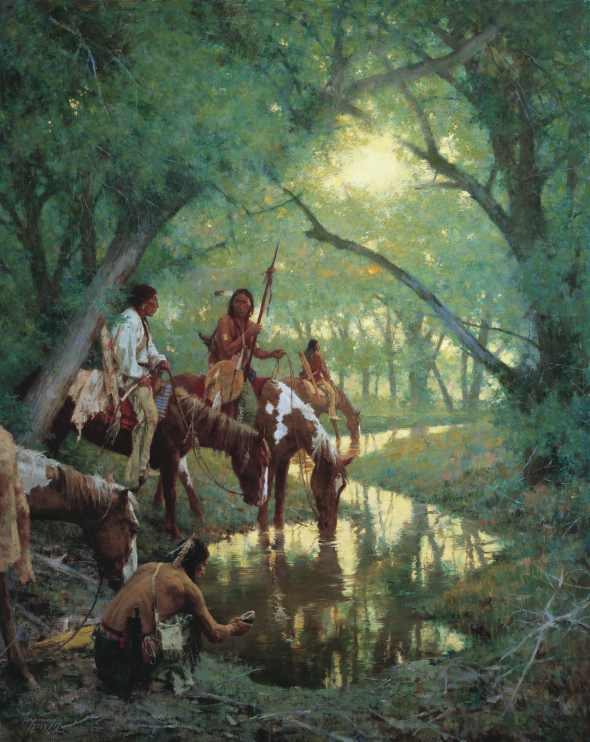

Howard Terpning is widely regarded as the greatest living painter of the Native American West. Among indigenous people dwelling today across the deserts, high plains, and foothills of the Rocky Mountains, he is known reverently as “the storyteller.” The same kind of dramatic flair that the novelist Larry McMurtry puts into his Westerns with words, Terpning wields mightily with a brush and colorful palette.

© Terpning Family Limited Partnership, LLC, Courtesy of the Greenwich Workshop®, Inc.

His narrative portrayals of Native American tribal ceremonies, oral traditions passed down over countless generations, and significant — sometimes tragic — events drawn from the past, are considered important historic touchstones. As the late Western art historian Anne Morand, former curator of art at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, told me, Terpning, in his own way, is akin to the great Renaissance painters of Florence and Rome who opened windows into antiquity, breathing life into human dramas that happened at a time when there were no cameras available to record them.

Terpning’s epic masterworks have sold for more than $1 million and reproductions of his more popular pieces hang as decorative art in thousands of homes and offices. Meanwhile, the artist himself, whose studio resides in a neo-adobe abode in Arizona’s Sonoran Desert surrounded by tall columnar saguaro cacti, has been honored with practically every major award in Western art.

But even at age 87, Terpning, still active behind the easel, acknowledges there is a special thrill that comes with achieving a feat that had eluded him all these years, seeing one of his pictures make the cover of The Saturday Evening Post. With pride, Terpning told me recently, landing the cover of this edition of the Post now elevates him into a distinguished, exclusive club that includes American masters who influenced him nearly 70 years ago. Painters like Norman Rockwell, J.C. Leyendecker, and John Clymer.

“The Saturday Evening Post represented the summit. For an artist, getting the cover was a feat of enormous prestige because it was so high profile,” Terpning says. “With a single image, you could influence the way millions of people in this country thought about a topic.”

For 25 years, Terpning toiled as a magazine illustrator, having studied under Haddon Sundblom (the artist made famous for portraying Santa Claus in ads for The Coca-Cola Company). During that period, Terpning’s illustrations adorned the pages of Reader’s Digest, Time, Newsweek, Field & Stream, and Good Housekeeping, among others. And he was tapped by Hollywood to create movie posters for some of the best-known films of all time, such as The Sound of Music, Lawrence of Arabia, Cleopatra, Dr. Zhivago, and 75 other movies.

Still, his greatest passion has been authentically depicting aboriginal tribes in the West, a fascination that started in his youth on a trip to Colorado.

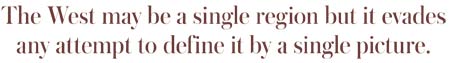

The West may be a single region but it evades any attempt to associate it with a single place or to define it by a single picture. More or less, it begins, geographically speaking, around the 100th meridian west and extends to the incoming tide of the Pacific Ocean; north to south, it arguably begins its spatial descent at the Arctic Circle and wends downward along the path of the Old North Trail (the route that various tribes followed at least 12,000 years ago) and reaches across the U.S. border into Mexico.

Terpning says his early career as a commercial illustrator first in Chicago and then based in Connecticut, taught him how to work fast to meet tight deadlines and to distill the essence of a scene down to its simplest elements.

“As young artists, we couldn’t wait to run down to the newsstand and see what Rockwell and others had on the latest Post cover,” he says. “Many of those Post artists ended up in the West. Tom Lovell and John Clymer were at the top of their game. They blazed trails with their portrayals of history.”

© Terpning Family Limited Partnership, LLC, Courtesy of the Greenwich Workshop®, Inc.

In the late 1980s before he passed on, I had an opportunity to interview Clymer about the work he did for this magazine. Born in Ellensburg, Washington, in 1907, Clymer had received tutelage from Harvey Dunn, a student of the legendary Howard Pyle, considered the godfather of what became the Golden Age of Illustration. Notably, Clymer had also been a colleague of Post artists N.C. Wyeth and Dean Cornwell.

Clymer’s first cover for the Post was completed prior to World War II. It featured a view of Alaska’s Inside Passage with a totem pole in the foreground and U.S. Navy destroyers and aircraft in the background. Even with this view of the West — in this case the far Northwest — a message was being sent via the Post. And it was to potential adversaries that the U.S. was a power to contend with, Clymer said.

Half a century later, I visited Clymer in his studio in Teton Village, Wyoming, and he recalled the transition he made by moving west to be in the middle of the geographical milieu he loved best. “I like to do, and always did, what you call storytelling pictures,” Clymer told me. “With illustrations you had only two or three days to get the work finished. Here, you have two or three months — as long as it takes to get it right. This type of work finally became accepted as Western art and was viewed as more than merely Western illustration.”

Clymer and Terpning have been giants in contemporary Western art, part of a tradition of visually interpreting the region that dates back to the first pictographs and petroglyphs carved into the alcoves of sandstone cliffs.

As a distinct category of fine art, the Western genre came to the attention of the world with Romantic portrayals of cowboys, Indians, wildlife, and geography in the latter decades of the 19th century. Painters such as Albert Bierstadt, Thomas Moran, Frederic Remington, and Charles M. Russell — whose works can be seen today in America’s premiere museums — cultivated a larger than life, mythological impression of the West.

© Terpning Family Limited Partnership, LLC, Courtesy of the Greenwich Workshop®, Inc.

Clymer shared his thoughts about striving to portray historic events as they actually happened and not filtered through an over-romanticized lens. “The movies and the early writers gave the world an impression of what the West was like. It’s partly true and partly not true.”

Clymer — and Terpning, too — set out to paint for posterity events such as the Lewis and Clark Expedition and mountain man trapper rendezvous. “I don’t paint the Battle of the Little Bighorn,” Clymer told me. “I don’t paint Custer. I wouldn’t touch that one with a 10-foot pole because it’s been chewed to pieces. But there are subjects that have never been done.”

Clymer credited the Post assignments with building his confidence, giving him a loyal legion of viewers who knew his work, and with knowing how to deliver scenes with high impact. Both Clymer and Terpning told me of their reverence for the artists who were there to witness the last gasp of the Wild West. “[Charles M.] Russell commented that as soon as white settlers started to show up, there went the reign of native people and along with them the bountiful game such as the buffalo. He painted Indians with grace and empathy,” Terpning says. “Other artists were aware that one kind of human relationship with the West, that had existed on this continent for thousands of years and was older than the Egyptian pyramids, was about to be lost forever. Replacing it was something else.”

Since that time, the West has continued to evolve through different cultural iterations, including cowboys, ranch and rodeo life, the era of oil wildcatters, loggers and fishing fleets in the Northwest, tourism in national parks, and the sprouting of retirement communities for northern snowbirds fleeing wintery weather. All of these themes were explored on covers of the Post.

Changeless, however, have been the purple mountains’ majesty, the big open vistas, and the sense that inside the West a person can still reinvent himself. Rising as bold declarations of regional identity have been depictions by pure landscape painters.

The oldest and most prestigious Western art show — indeed it serves as a barometer for gauging excellence — is the Prix de West Invitational, hosted annually by the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. One of the most eminent artists in recent years at that show, and one who commands Terpning’s admiration, is George Carlson. He, too, started his career as a commercial illustrator and hails from the same birthplace as Terpning — Chicago.

Carlson, who now lives on a lake near Harrison, Idaho, is the only artist to win the Prix de West Purchase Award in two separate media, first as a sculptor and more recently as a landscape painter. Terpning and cowboy and Indian painters Tom Lovell, Martin Grelle, William Acheff, and Morgan Weistling are the only other two-time winners in painting. The late Hollis Williford notched double wins for his work in bronze.

“The grandeur of the West needs no embellishment as it received in the past. There is plenty of space for the human imagination to wander around and experience its mystery,” Carlson says.

© Terpning Family Limited Partnership, LLC, Courtesy of the Greenwich Workshop®, Inc.

Earlier in 2015, Carlson won the top award at the Masters of the American West show sponsored by the Autry National Center & Art Museum in Los Angeles for the piece Witness of Time. The painting is a depiction of the geographical area known as the Channeled Scablands in eastern Washington and northern Idaho that was gouged by an epic glacial flood. Stark and serene, Carlson says it conveys the real spirit of the West.

“For an artist, the landscape will breathe you in if you let it,” he says. “In order to feel the rhythms and vibes of color and then to translate it through your own emotions, you have to allow yourself to become immersed. To me, that’s what great art from the West does — it translates the feelings and moods and senses of place that cannot be communicated in words.”

“Our beloved West is still coming of age,” says William Kerr, who with his wife, Joffa, founded the National Museum of Wildlife Art in Jackson, Wyoming. “My native region is big, bold, and beautiful. It is also selfish, wasteful, and like other areas of our country, parochial,” he says, noting that what’s required is an honest assessment of the toll wreaked by Manifest Destiny and the false notion of a limitless frontier.

Kerr, the son of former U.S. senator and Oklahoma governor Robert S. Kerr, recalls that his home state was historically a place where eastern Indian tribes were “resettled” after being uprooted from their homelands and exiled west along the Trail of Tears, themes that Terpning and others have explored. “Art in its purest forms is truth telling,” Kerr says.

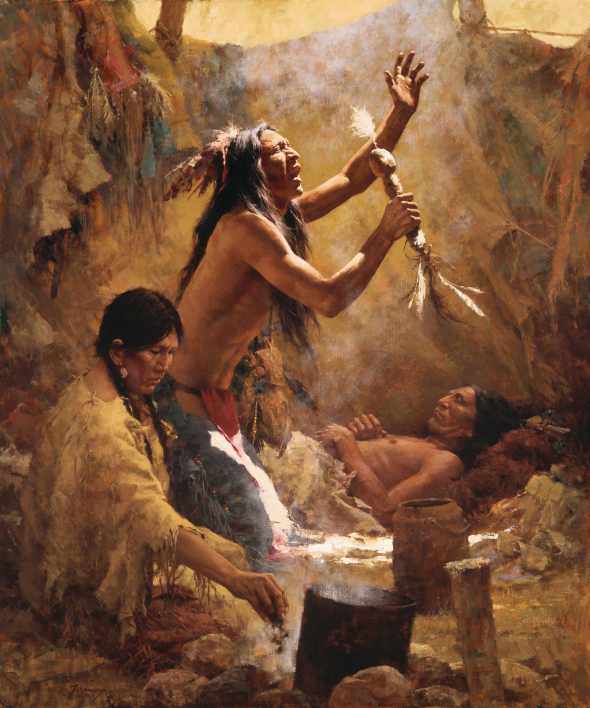

For his part, Terpning hopes that viewers see in his Native American works universal human qualities. His Medicine Man of the Cheyenne, for example, is based on actual accounts. It features a medicine man who is attempting to heal a fellow Cheyenne tribal member using traditional remedies and prayer. In the foreground is a helper sprinkling sage and burning sweetgrass and juniper as part of a sacred ritual. The work conveys a kind of spiritual experience, unexplainable perhaps on a printed page, yet timeless. A place of fact and fiction, reality and the dreams of possibility. “The West doesn’t belong to any one thing,” Terpning says. “It is our common story.”

Scott Usher, president of Greenwich Workshop, an art publisher that markets reproductions of Terpning paintings around the world, says Terpning is respected for the depth of research that goes into each new work. He knows how buffalo rugs were tanned, the process that went into making bows, arrows, and arrowheads, and the precise nuances of individual ceremonies.

Terpning has been invited to sacred rituals normally not accessible to outsiders. His voice cracking with emotion, he says, “I’ve felt touched and honored that traditional elders, who have become my friends over the years, trusted me enough to let me into their camps. They see a little of themselves in my paintings, and for me there’s been no greater satisfaction.”

“When I think about Howard Terpning’s legacy, I put him in the same category as Rockwell. The imagery he created for The Saturday Evening Post grow in importance with each passing day,” Usher says. “A century from now, Terpning’s portfolio of Indians in the West will be treated with the same level of respect now afforded Remington and Russell.”

© Terpning Family Limited Partnership, LLC, Courtesy of the Greenwich Workshop®, Inc.