Fear of FERA: A New Class Struggle during the Great Depression

The crisis created by the Great Depression was like nothing the United States had ever seen, and the federal government had to scramble to create programs that addressed the nation’s problems. FDR’s Civilian Conservation Corps, for instance, put young men across the U.S. to work on important, useful, long-lasting projects. But many programs of the time were both more controversial and less successful.

With an unemployment rate that reached as high as 25 percent, state and local welfare systems that had been established primarily to deal with “the unemployable” — the blind, the deaf, orphans, the aged — were faced with a growing population of educated, experienced, but unemployed adults. In 1932, President Hoover established the Federal Emergency Relief Administration to help states create new unskilled jobs in local and state government and get people back to work.

But by 1935, FERA had grown into something that looked more permanent, was a drain on taxes, and simply wasn’t improving the situation. What’s more, as Dorothy Thompson argued in “Our Ghostly Commonwealth,” FERA was leading to a new class struggle — “not the class struggle according to Marx — not the workers against the capitalists, but the working against the workless, the haves against the people they support.” And it was creating the same type of social and economic environment that had allowed Adolf Hitler to seize power in Germany.

Our Ghostly Commonwealth

By Dorothy Thompson

Excerpted from the article originally published July 27, 1935

There exists in the United States, alongside our so-called normal social and economic life, another commonwealth, a ghostly one — ghostly because it is largely invisible to those who are not its members, and ghostly in the vague uneasiness which its haunting presence provokes. It is a commonwealth of people who live in a separate world of their own.

They are not isolated in some distant state, on some reservation set aside for them, but they live in the midst of us, in our cities and villages, in our very streets. They can vote — although it is suggested in some states that they should not — they look like the rest of us; they have the same desires, the same needs, the same urges. But not exactly, and always decreasingly, the same hopes. They belong to the same trades, professions, crafts, and skills as the rest of us, and, on the whole, to the same races, although there is a larger proportion of Negroes amongst them than in the other society, our own society, and a slightly larger proportion of Mexicans and Filipinos. There are mechanics and farmers, engineers and executives, lawyers and journalists, artists and teachers, laborers and musicians, dancers and actors, miners, carpenters, stonemasons, clerks, stenographers. They are, indeed, a pretty fair cross section of the United States. There are stockbrokers amongst them, and former $50,000-a-year men, and sharecroppers who never in their lives have handled more than $100 a year in cash money. And lots and lots of children. Curiously, there are, proportionately, rather more children amongst them than the rest of us have. They constitute between one-sixth and one-seventh of our population, because, all together, their number is around 20 million, and the experts tell us there are an additional 25 million potential members of their society.

They are the people on relief.

But the people on relief are not usually referred to as “people.” The society in which they live has a nomenclature of its own, as well as a social and economic organization of its own. They are usually referred to as “clients” or as “cases,” and, in groups, as a “case load.” Thousands of them live in barracks, under the supervision of Army officers, but they are not soldiers. They and many of the others work, and at all sorts of tasks: construction, manufacturing, transportation, education, building, mechanics, drafting, moving pictures. They play instruments, sew clothes, manufacture mattresses, till farms, but they do not work at jobs, but on “projects.” They work, but most of them do not receive wages, but “budgets,” and the amount which they earn is not decided according to their merits, but according to their minimum needs — as determined for them by careful investigation. They produce all manner of things, from iron cots and refrigerators to pictures and plays, but they may not sell anything they produce.

Their lives for 10 years back are investigated, recorded, catalogued, and cross-catalogued. More is known about them than about any other part of the population — about their race, and skills, work histories, diseases, even about their personalities — but the knowledge is in the files of state and federal government agencies, and is not part of the public awareness. In so far as the rest of our society is conscious of them, the attitude is a combination of bad conscience and hostility, and of this attitude they are also aware — and repay it, on their part, with a feeling of frustration and hostility.

Limitations of Local Relief

The poor have long been the charges of state, county, and township governments. But possible taxation for such purposes was severely limited. And the whole mentality of local poor administrators was awry. To them, the destitute were so because they were simply misfits. It was, in essence, their own fault. The attitude was embodied in some New England states by laws which disfranchised recipients of public relief. The local poor-law authorities were trained by tradition and experience to take care of the ne’er-do-wells, the village idiots, the aged, the infirm, the orphaned. But they were not prepared for a program of relief for Thomas Smith, able-bodied, aged 35, six years ago receiving a salary of $25 a week and a so-to-speak house owner, meaning that he had a house “worth” $5000 on which he had a $4000 mortgage; four years ago cut to $20; three years ago cut to $12, and unable to pay the mortgage; two years ago dismissed because of “lack of business,” and today totally without resources.

President Hoover, with the experiences of the war, the Belgian relief, the all-European campaign against typhus, the 1930 drought, and the Mississippi flood behind him as justification, believed that there was sufficient goodwill, energy, and organization power in the American people to deal with the administration of this problem on a local and largely voluntary basis.

But the analogy with the war and with President Hoover’s previous great relief administrations was fallacious in one important particular. The war, the postwar starvation, the drought, and the Mississippi flood were catastrophes which affected all parts of the population. People starved in postwar Belgium because there was actually no food. Everybody starved. The good and the bad, the poor and the rich, the deserving and the undeserving. In the war, the banker’s son needed bandages as well as the truck man’s. And the Mississippi rose upon the just as well as upon the unjust, upon the efficient as well as the unlucky. There was solidarity of action because there was solidarity of distress.

No such solidarity of experience exists between the employed and the unemployed. But one thing which President Hoover foresaw has come to pass. Many of the fortunate, being isolated from any participation in the troubles of the unfortunate, except to pay for them, are developing a callousness and hostility toward them which aggravate the whole social situation, and which no amount of press releases from the publicity bureaus of the various relief administrations can dissipate. This country is dividing into two classes — the employed and the people on relief. A genuine class struggle is emerging, but it is not the class struggle according to Marx — not the workers against the capitalists, but the working against the workless, the haves against the people they support.

The Working and the Workless

This is reflected in almost every conversation which one may have with people whom the depression has not touched severely. The Long Island ladies who are indignant that they cannot get a handy man to help lay a carpet; the newspaperman who has kept his job securely all through these last five years; the employers of cheap labor who can’t find men at prices they can afford to pay. Being cut off from the problem, which is isolated behind a bureaucracy, they generalize from their own experience, and there are plenty of experiences to bear them out. They see the relief problem in its bulk and implications only in the un-quieting growth of the extraordinary budget.

In the great cities, in the winter of 1932, the attempts at local relief had certainly broken down. The local charities were bankrupt. Milkmen could not deliver milk, because their cars were overturned and the milk looted. Grocery windows were smashed. There were riots. Gangsters joined the ranks of the unfortunate, and racketeering was coupled with destitution. There was a clamor from all quarters that something should be done.

And President Roosevelt came in, surrounded by youth and social indignation, pledged to action, and a lot of it. And gallantly flinging back their locks from their foreheads, and with a smile cheery and brave, this administration gathered the whole kit and caboodle of the destitute to its bosom.

Since then it has been exceedingly busy trying to bounce many of them off again.

The federal government had no more experience than anyone else in being an eleemosynary institution. It had vast quantities of goodwill, optimism, and idealism. It was manned with as attractive a crowd of people as ever were got together in Washington; for eagerness and earnestness, youth and enthusiasm are extremely attractive qualities. It is probably the most literate administration that this country has ever had since the early days when politics was believed to be a gentleman’s profession, and it is certainly the most talkative. It is also probably one of the most truly representative of administrations, for it shares practically all the illusions of the typical American intellectual. It believes that any action is better than none; that the scientific attitude is synonymous with being willing to try anything once; that economic reform can be interpreted in terms of social uplift; and that the lion and the lamb can be brought to lie down together by persuasion.

This is preeminently the administration of goodwill — on all sides. But the good, says the proverb, die young. It is the wise who die of old age.

A Sympathy All-Embracing

This administration has been truly encyclopedic in its sympathies. It has tried, in the midst of depression, to raise wages and preserve profits. It has encouraged monopolies and sought to protect labor. It has advocated high prices and the protection of the consumer; [Secretary of State] Mr. [Cordell] Hull wants to restore international trade, and so does [Secretary of Agriculture] Mr. [Henry] Wallace, but meanwhile Mr. Wallace scales down production to domestic consumption. It believes in inspiration and in the expert.

Now, the same ambivalence of feeling dominates the relief program. The Federal Emergency Relief Administration is accurately described by one word in the title, and somewhat accurately by another. It is almost “Federal,” and it is certainly “Administration.” But no one whom I have been able to find in the whole organization, whether in Washington or in the field, believes that it is “Emergency.” On the contrary, its members are convinced that we are settling down to deal with a permanent problem, and they are directing policy with this in view. It is not relief. It is — or intends to become — a system of employment and, as such, should be no more relief than the check I hope to get for this article.

The destitute, in the mind of this government, have a right to support. But there is something humiliating about the exercise of this special right. Therefore, work must be provided for them. But the work must not interfere with private industry. The relief worker must be free, but in order to live on his budget, he must be controlled. The relief worker must not be insulted, but the public must be scrupulously protected. The problems of the immediate present must be met. The problems of a distant future must be met. The chief aim must be to provide immediate projects to meet the needs of the individual unemployed; the chief aim must be to construct lasting works of public importance. Every destitute person in the country must be relieved, but the taxpayer must not be overburdened.

Benevolent Serfdom

I am amazed that some people consider that the work-relief system is a form of socialism. Go out and look at it, and you see that it is actually a new form of benevolent serfdom. I say “benevolent” because almost all the people in administrative positions from top to bottom are full of human kindness, full of sympathy. They are not well-paid themselves. They work extremely hard. They are, for the most part, vigorously honest. And most of them know that this system will not work in the long run. Some of them foresee its extension into a universal program of production for use, a sort of nationwide EPIC. Others believe that the government must openly compete with private industry and gradually expropriate it. They should observe that no country yet has managed to edge its way into socialism. Others believe that such a system can only be integrated with the rest of society by political means.

Now, the political means of integrating such a society with the rest is fascism. It is, as far as I know, the only political means which has been pragmatically successful.

Germany, from 1925 onward, built up a system of work relief very similar to this one. In fact, it is the only parallel which I can find in a study of social service in European countries. It had the same sort of projects — subsistence farms, unemployed production for unemployed, and in the Voluntary Works Corps, an organization not unlike CCC. It did not, under this system, stabilize the social order. The resentment of the unemployed against the state was prodigious.

According to the classes from which they came, the younger elements flocked to the extreme right or the extreme left. They furnished strong support for Hitler. And when he came into power, he took over the whole system. It was literally ready-made for him. He reorganized it along military lines. He put the workers in camps into uniforms, and the social workers, to a large extent, as well. He kept the system and changed the psychology.

Now the subsistence workers are not pariahs of the social order but are hailed as its pillars. They are the builders of the New Germany. They have parades. They are drilled, exercised, trained. Arrangements are made to keep many of them permanently in this status. And a vast propaganda machine with the whole field to itself is busy persuading them that they like it.

Well, perhaps they do. But would we?

President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 7034 less than three months before this article was printed, establishing the more ambitious and unconventional Works Progress Administration. Like FERA, the WPA was accused of promoting communism, socialism, fascism, corruption, and political favoritism. But its results are difficult to argue against: 651,000 miles of roads, 124,000 public buildings, 800 airports, and 124,000 bridges built or improved; 225,000 public concerts presented; 475,000 works of art and 276 full-length books created; plus public swimming and wading pools, utility improvements, and over a billion school lunches.

FERA was dissolved in December of the same year.

Read Dorothy Thompson’s “Our Ghostly Commonwealth” in its entirety.

American Civil War Atrocity: The Andersonville Prison Camp

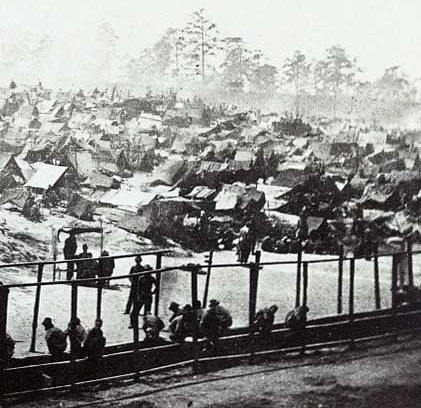

Of the 45,000 Union soldiers who’d been held at Andersonville Confederate prison during the American Civil War, 13,000 died. During the worst months, 100 men died each day from malnutrition, exposure to the elements, and communicable disease.

Restoring unity in America after the Civil War was never going to be easy. Too many Americans felt they could never forgive wrongs committed by the enemy during the conflict. Southerners could point to the destruction wrought by General Sherman’s army on its destructive march through Georgia and South Carolina. And Northerners could point to Andersonville.

This Confederate prisoner-of-war camp, which opened 150 years ago this week, was built in southeast Georgia to hold the Union prisoners who could no longer fit into Virginia’s prison camps.

Its stockade, in which prisoners were detained, measured 1,600 feet by 780 feet, and was designed to hold a maximum of 10,000 prisoners.

The prisoners arrived before the barracks were built and so lived with virtually no protection from the blistering Georgia sun or the long winter rains. Food rations were a small portion of raw corn or meat, which was often eaten uncooked because there was almost no wood for fires. The only water supply was a stream that first trickled through a Confederate army camp, then pooled to form a swamp inside the stockade. It provided the only source of water for drinking, bathing, cooking, and sewage. Under such unsanitary conditions, it wasn’t surprising when soldiers began dying in staggering numbers. The situation worsened as the camp became overcrowded. Within a few months, the population grew beyond the specified maximum of 10,000 to 32,000 prisoners.

After 15 months of operation, the camp was liberated in May of 1865. Of the 45,000 soldiers who’d been held at Andersonville, 13,000 died. During the worst months, over 100 men died each day.

News of the conditions at Andersonville came slowly to the North. The name wasn’t even mentioned in the Post until the following March, when the notices on page 7 announced the death of Robert Price “at Andersonville, Ga.…of chronic diarrhea.” A member of the 118th Pennsylvania Volunteers, he “was taken prisoner by the rebels, May l5th, 1864” and managed to survive just three months in the camp.

As news of the death camp reached the newspapers, Northerners were newly enraged at the South and its army. Hearing of the miserable conditions and high death rate in the camp, Walt Whitman wrote, “There are deeds, crimes that may be forgiven, but this is not among them.”

Andersonville’s reputation was widely known when its name next appeared in the Post. In 1865, the Post’s front page featured a poem by Miss Phila H. Case, “In the Prison at Andersonville.” In this sentimental ballad, a narrator and his brother Ned are captured and shipped to Andersonville, where the brother soon sickens.

“He faded day by day—a prayer

Upon his lips for one sweet breath—

What wonder when the reeking air

Was chill and dank with dews of death.

But why delay my tale—he died

And careless hands bore him away,

For what was one when, side by side,

Hundreds were dying every day?”

In July, 1865, the Post reported “the former Rebel commandant [Jeff Davis] of the Andersonville prison is to be put on trial at Washington this week before a court-martial.” It adds no further comment, but an item just a few lines lower on the page reflects the bitterness many in the North were feeling. “Jeff Davis is reported, by the latest advices from Fortress Monroe, in the best of health and spirits.”

Many Northerners had expected the Federal government would hang the president of the Confederacy once he was caught after the war. But Davis, though indicted for treason, was never brought to trial. At the time the Post item above appeared, he was, in fact, living in leg irons and gravely ill. At the end of two years, the federal government released Davis on a bail of $100,000. The money was donated by Southern supporters as well as former Northern adversaries.

Andersonville’s commandant, Major Henry Wirz, didn’t fare quite as well. He was brought before a military tribunal in August of 1865 and charged with actions intended “to injure the health and destroy the lives of soldiers in the military service of the United States.” The court also charged him with murder “in violation of the laws and customs of war.”

There was no doubt Wirz allowed thousands of Union prisoners to die from exposure and malnutrition. Hundreds of ex-prisoners testified to his brutal punishments. But his defenders, both then and now, have offered several arguments in Wirz’s defense.

The federal government was partly to blame, they said, because it had halted its prisoner-exchange program.

By 1864, the Union army no longer believed it would win the war by a decisive strategic victory on the battlefield. It would have to win by attrition; that is, by wearing down the number of Confederate soldiers by death or capture until the Southern army could no longer fight. This strategy could work because the North had a greater population, and could replace the soldiers it lost, which the South couldn’t.

But the attrition strategy only worked if the Union refused to let its Southern prisoners return home and back into the Confederate army. In return, it meant Union prisoners would have to wait out the war, gathering in growing numbers in Southern prisons that barely had enough resources. However, the policy put a strain on Union camps as much as on those in the South.

Defenders of Wirz also point out the standards of hospitality were low in all prisoner-of-war camps. At the Union army’s camp at Rock Island, IL, for example, 1,300 Confederate soldiers died from an outbreak of smallpox. However, the Rock Island garrison eventually built barracks and a hospital to halt the smallpox epidemic. There were no similar improvements at Andersonville, where the death rate was four times higher than at Rock Island.

Others argued that the Confederacy couldn’t provide for its prisoners because it could barely provide for itself. The South was plagued by shortages because of the Union navy’s blockade of its coast, and the exorbitant costs of supporting its military, which left few resources for feeding or sheltering its prisoners.

These costs, however, were the unavoidable consequence of starting and continuing the war. Union soldiers had given themselves into the Confederacy’s care with the expectation of reasonable safety. Yet the soldiers who marched into Andersonville had less chance of emerging alive than the soldiers who marched onto the battlefield of Gettysburg.

The questions of guilt were troublesome. Obviously it took more than just Henry Wirz to make Andersonville possible. But once a court starts appointing guilt in wartime, it’s hard to tell where it ends.

In this case, it ended with the hanging of Major Wirz in November of 1865. The federal government was so reluctant to appoint blame that he became one of only three Confederates executed for their atrocities during the war.