Jekyll Island and the Secret Behind the Fed

In Frederick E. Allen’s article from our May/June 2012 issue, we tackle the issue of big banking and how banks grew to be too big to fail. The following piece offers more historical insight on this and the foundation of the Federal Reserve.

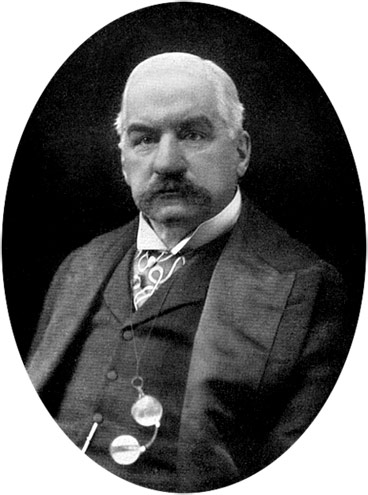

The Federal Reserve is an independent central bank that derived its power in the aftermath of the Panic of 1907—a crisis caused by several factors: contraction of money supply, falling stock prices, and a failed attempt to corner the copper market. Leery of banks, depositors withdrew savings in droves. The run ignited widespread concern in banking circles and Congress. As the crisis unfolded, prominent financier J.P. Morgan intervened, using his money (and recruiting help from fellow bankers) to keep banks afloat and prevent the New York Stock Exchange from going under. Many considered Morgan a hero for saving the economy, but the perception changed as the public came to believe Wall Street bankers actually caused the panic.

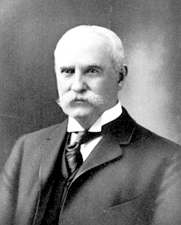

In response to the outcry for banking reform, Congress created the National Monetary Commission to review bank policies and develop a sound national monetary system. Chairing the Commission was Senator Nelson W. Aldrich, who, closely aligned with bankers, had no intention of leaving them out when crafting the Federal Reserve Act—not an easy task given the public’s attitude against the concentration of wealth and power.

But something had to be done. At the request of Senator Aldrich and Assistant Secretary of the Treasury A. Piatt Andrew, five of the nation’s top financiers arrived at the exclusive Jekyll Island Club on the Georgia coastline for one purpose: to devise a plan to restructure banking in America.

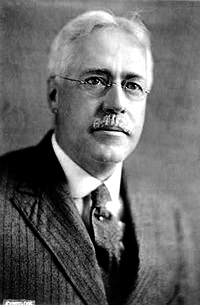

In “From Farm Boy to Financier,” an article in the February 9, 1935, issue of the Post, author Frank A. Vanderlip—a leading banker and former Assistant Secretary of Treasury for President William McKinley—chronicled the top-secret meeting that helped create the Aldrich Plan, which would frame the Federal Reserve Act.

In the Post story, Vanderlip outlines events leading up to the meeting on Jekyll Island. Aldrich had visited central banks in Europe and returned to the U.S. with no firm plan to address the crisis. Concerned about the report he was expected to present as a bill to Congress, Aldrich concocted a scheme to bring together an elite group to help draft reforms. To ensure secrecy, Aldrich invited five key leaders from banking and government—Henry Davison, A. Piatt Andrew, Benjamin Strong, Paul Warburg, and Vanderlip—to the isolated Jekyll Island Club—“without a journalist within 50 miles.”

Vanderlip recounted how the men arrived “… one at a time and as unobtrusively as possible to the railroad terminal on the New Jersey littoral of the Hudson, where Senator Aldrich’s private car would be in readiness, attached to the rear end of a train for the South.” So great was the need for secrecy that last names were taboo—even among the five men. The train crew was kept unaware of the identities of the car’s prominent passengers to prevent any leaks to the press.

“We were taken by boat from the mainland to Jekyll Island and for a week or ten days were completely secluded, without any contact by telephone or telegraph with the outside. Even the servants had no idea who the men were. We had disappeared from the world onto a deserted island…. We worked morning, noon and night…. We stuck to our plan of putting down on paper what we agreed upon.”

Vanderslip acted as secretary. In the Post, he describes in minute detail the plan beginning to take shape. At issue was the fact that the country hadn’t had a central bank for 75 years and a belief that the lack of central authority was responsible for the current financial crisis. But establishing a new national bank was perceived as a dangerous recipe for excessive power and corruption: “If it was to be a central bank, how was it to be owned—by the banks, by the Government, or jointly? Should it restrict its services to banks? What open-market operations should be engaged in? … at the end of our week, we had whipped into shape a bill that we felt, pridefully, should be presented to Congress …. We returned to the North as secretly as we had gone South. Senator Aldrich would present the bill we had drafted to the Senate. It became known to the Country as the Aldrich Plan.”

Unfortunately when Congress was slated to meet, Aldrich was “too ill to write an appropriate document to accompany his plan.” Strong and Vanderlip went to Washington and prepared that report. However, at the time, both political parties opposed the idea of a central bank as did a distrustful public, so the bill was defeated. But as Vanderlip wrote, the Jekyll Island group’s plan greatly influenced the final Act eventually adopted by Congress: “Although the Aldrich Federal Reserve plan was defeated … Aldrich undoubtedly laid the essential, fundamental lines which finally took the form of the Federal Reserve Law.”

To read Frederick E. Allen’s article on banking, go here.