North Country Girl: Chapter 43 — Sweet Home, Minnesota

For more about Gay Haubner’s life in the North Country, read the other chapters in her serialized memoir.

There was something about me that triggered a Svengali-like impulse in my older lover James, who had swept me off my feet and into his Acapulco beachfront condo. James loved playing the worldly sophisticate and I was a young sponge, eager to soak up every detail of the kind of life that a year ago I had no idea even existed.

While I did learn to drop that water ski, I never picked up any of the disco dance steps James excelled at (“Do the Hustle!”). James did get me to give up the arm flailing for smooth lifts and shrugs of my shoulders, movements that were occasionally in time with the music. He taught me the complicated economics of tipping: who, when, and how much; we lived in bars, clubs, and restaurants where we never had to wait for a table and drinks appeared and were replaced as if by magic.

After one raised eyebrow from James I stopped ordering White Russians before dinner, and even after. James instructed me to slowly sip the Remy Martin he always finished with, and it was fun sticking my whole face in those enormous snifters. When we dined out, James asked me what I would like to eat and then ordered it for me while I smiled and blinked at the waiter like a deaf mute. James taught me how to do the New York Times crossword puzzle and to play backgammon, and I quickly became better at both of these than he was, though neither of us would admit it. I was always a penny ante gambler: if I lost five dollars at backgammon I felt a pang in my stomach; that five dollars could have bought an economy-size box of the frozen fish sticks I survived on a year ago.

James believed that it was gauche to wear anything less than 18 karat gold; his own heavy chain was 22 karat. One afternoon, he led me into a chic boutique across from his condo, where he ordered a custom-made piece of jewelry, not another chain for himself but a necklace for me. That year, all the girls in Acapulco wore gold pendants spelling out their names. James got off cheap buying only three letters, and in that time and place I could wear GAY around my neck without too many double takes and annoying comments.

To my pleasure and amazement, I had a man buying me jewelry in an elegant store, even if I did end up with the least expensive piece possible. While James was consulting with the saleswoman on the right font and chain for my necklace, I was eyeballing the display of uncut emerald rings and hoping one of them might be in my future. A ring with even the smallest uncut emerald would still make me inordinately happy.

It was a wonderful dream I never wanted to wake up from, but my time in Mexico with James was coming to an end. May is the start of the rainy season in Acapulco, the end of the party season. The lease was up on the apartment and the rented jeep; James was headed back to Chicago. The French Canadian girls had vanished; I hope they all landed wealthy fiancés. The crowds had thinned out at Armando’s and Carlos’N Charlies. Even Fito was leaving, Jorge told me, for a gig in Mexico City.

I checked my bankroll of Pracna one dollar bills; it was almost the same size as it had been when I stepped off the plane. When I was with James, I never had to carry anything in my purse besides lipstick and a comb. I had more than enough to fly back to Minneapolis and keep me going till I figured out what was going to happen next.

James and I had our last dinner at Carlos‘N Charlie’s, our last dance at Armando’s, and did our “Wow, it’s been great” farewells. Then to my surprise, James asked for my phone number. My number? I had no idea of where I would be living; I could have given him my mother’s phone, but my gut said no. James scribbled his number on a piece of paper, told me to call him, and we kissed, a kiss that did not feel like goodbye.

I had no idea what I was going to do back in Minneapolis. I was counting on Pracna to hire me back; no one had been mad that I left with literally no notice, and with the return of summer I knew the place would be swamped with customers. But where could I live?

Even if she had kept our crappy apartment, I could not ask Liz to take me back; I had proved to be the most unreliable of roommates. Mindy and Patti shared a tiny studio that was barely big enough for the two of them. Eduardo had that big apartment, but it would have been weird to ask to stay there whether he was back with Patti or not. And for all I knew, Eduardo might have finally received his academic walking papers and be off at another, more lenient, college, or he could be back home in Miami, being force fed mondongo.

I got off the plane in Minneapolis, went to a pay phone, and stayed there pumping the same quarter in again and again until my old boyfriend Steve finally answered his phone. By a miracle, I had caught him on his last day in the Middlebrook dorm. He gave me the address of his new place and said he would meet me there.

Once again I stood outside a guy’s apartment with my pink Samsonite suitcases, waiting to move in uninvited. Unlike Jorge, Steve was happy to see me. Very happy, in fact. It had been almost a year since the last time we were together, an intense bout of sex in his dorm bed followed immediately by an epic fight when I found a pair of panties, not mine, in the sheets.

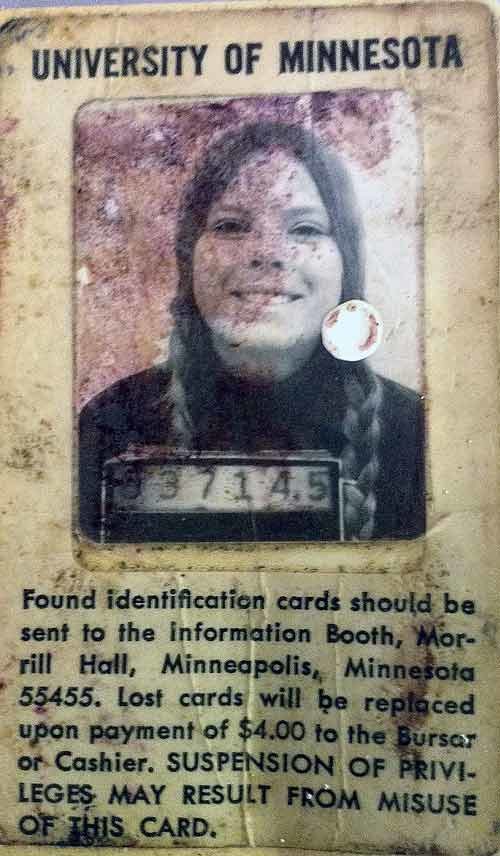

Now I was very thin (thanks to James), very tan, and very blonde. I tried to radiate a new sophistication, hoping that my recent Mexican adventures had made me more exotic and desirable than the nerdy brunette from Duluth Steve had met our freshman year. That girl was dead.

Steve looked exactly the same, small-town boy gone to the dark side, his smile still more of a sneer, costumed as the Caucasian Super Fly in a cheap white polyester suit. I couldn’t help but think that in that outfit, he would have been left standing in line all night outside Armando’s. But when we touched, that familiar and thrilling bolt of desire shot through me, making me catch my breath and hold him tighter. The two of us hustled up the stairs and into his new place.

It had taken years, but Steve had finally convinced Outward Bound to let move him out of the dorm and into an apartment of his own, an apartment they still paid the rent on. His new place was the top floor of recently built duplex not far from the university campus. A sign in front announced “Buttercup Complex Now Renting” or some such nonsense, but Steve’s building was the only one on the block: vacant lots surrounded the duplex on all sides, portioned out with stakes and string. The closest building was behind the duplex and across a field, a single story red brick creamery topped with a huge billboard featuring the Land O’Lakes Indian maid with her butter, her mysterious smile, and her plump knees sticking out of her buckskin garb.

Steve was upholding part of his deal with Outward Bound, puttering away nicely towards his degree in Accounting or Business or Pharmaceutical Sales. But he kept his eye on the prize and wanted to expand his drug dealing beyond his fellow dorm residents. He knew the quickest way to get busted and lose his scholarship would be to start buzzing in shady characters to his dorm room at all hours; drug dealing is the business that never sleeps. If he had his own apartment, he could expand his customer base and make even more money. Every few days he would drop into the dorm “to visit friends,” friends who in an emergency could come to him. He probably had a complete business plan, repurposed from some economics assignment, in place.

I can’t imagine that Steve’s benefactor from Outward Bound ever came to check up on him in his new digs, as there was always a wide sampling of drugs strewn across the coffee table, like a display case at a jewelry store. Most of his stash was tucked away in the freezer, while the cash was cleverly concealed in a Folgers coffee can on top of the bedroom TV. A steady stream of customers came by all day and pretty far into the night, as late as possible in a town where the bars shut at one. Sometimes they called first, sometimes they just showed up and banged on the door.

My original plan, concocted on the flight to Minneapolis, had been to hole up in Steve’s dorm for a few days till I found a place to live; but Steve welcomed me to stay as long as I liked in his apartment and his full-size bed, and I was happy to be there, happy to sit on his tiny back patio, smoking his pot with no one around except the Land O’Lakes maiden.

I did sneak in a quick phone call to James in Chicago. We talked about the weather and if I had signed up for summer classes yet. When conversation faltered I gave him Steve’s number to reach me without mentioning Steve himself.

I also phoned my mother to let her know I was alive. The only way to make a long-distance phone call in Acapulco was to go to the phone company, which was a shabby, un-air-conditioned edifice in the hot, steamy downtown. I did try to call my mom; I filled out the blurry form at the desk, and then stood in a long line waiting to enter a wooden phone booth, where I waited some more for the right number to be connected, which generally took two or three tries. I stood in that hot box, sweating and hoping someone would be at home to answer the damn phone. After my second fruitless attempt to reach my mother, the long-suffering look on James’ face as he sat smoking in the jeep discouraged me from trying again.

When I phoned her from Steve’s place, my mother was not as concerned about my going missing for six weeks as I thought she should be. She had a bigger problem. My sister Lani had appealed to have her custody switched to my father, and the minute that happened, dad gave Lani permission to marry her Colorado Springs boyfriend. The boyfriend was twenty-one, Lani was sixteen and about to be a June bride. Neither mom nor I were invited to the wedding. For some reason the fact that Lani had picked out a big virginal white wedding gown to get married in was what drove my mom over the edge. I knew she wasn’t listening to me, but I assured my mother I was fine, and hung up to the sound of her tearing out her hair.

As I had hoped, Pracna was happy to hire me back. They had opened the outdoor cocktail area overlooking the Mississippi River. People showed up at eleven in the morning to snag one of those tables, and every table outside and in was occupied till we closed the joint at one. I sweet-talked Steve into driving me to and from work, promising to introduce him to potential new customers, the hard-partying Pracna staff. I treated myself to a new pair of work shoes, lovingly tucked my growing bankroll into the empty shoebox, and slid the box way under Steve’s bed, till it rested back against the wall.

The deadline for enrolling in summer classes came and went. I was not ready to get back on the treadmill. I had always been an industrious ant; now I discovered that grasshoppers and blondes do have more fun. It was too pleasant waking up next to Steve, who was already rolling that morning’s first joint, and not having to go anywhere for hours. We were getting along better than we ever had before. Steve seemed mesmerized by the new me, and his outlaw life excited me enough to overlook his pimp-style wardrobe. Steve had grown up poor, his few articles of clothing were hand-me downs or from Goodwill, and children are cruel. He made up for that childhood deprivation now, with a closet full of candy colored wide brimmed hats, bell bottoms in every fabric except denim, shiny patterned shirts, and platform shoes of a tottering height that I would have plunged from, but that he managed to strut around in with aplomb.

Our only disagreements came from the fact that Steve did not want to leave the apartment. For a guy whose entire life was bankrolled by an outdoors education organization, Steve was reluctant to go outside. There were no cell phones, no beepers, not even answering machines, and he did not want to miss a single prospective buyer. But it was glorious summer in Minnesota, when the air is a balmy blessing and the grass a soft carpet. I was drifting along, with no thought for the future, but well aware that there were only a handful of summer days to enjoy. I wanted to be outside, coaxing what warmth there was to be had from the Minnesota sun on my still tan skin.

I would pout and fuss until I got Steve to drive us and a blanket and a bottle of something to Lake Calhoun (now Lake Bde Maka Ska) where we would snog publicly and smoke pot and drink surreptitiously, although in those days no one cared as long as we didn’t make a mess or too much noise. Sometimes I would get him out of his platform shoes and into a his old pair of hiking boots and we’d walk the trail to Minnehaha Falls, a bit of wilderness in Minneapolis that we often had all to ourselves. I even talked Steve into driving to the Corn on the Curb Festival, held in Le Sueur, home of the Jolly Green Giant, on the exact day when the corn stalks were as high as an elephant’s eye and the emerald fields waved gently under a summer sky bleached almost white. Steve claimed to hate small Minnesotan towns. But he took me anyway, after swallowing a few pills, and as his reward he got to see me eat twenty ears of corn while he pounded bottle after bottle of Schell beer and sneered at the yokels.