Considering History: Fanny Fern, American Original and Women’s History Month Icon

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

Writing witty and pointed daily newspaper columns under the pseudonym Fanny Fern (itself a parody of the pen name of one of the period’s most prominent sentimental writers, Grace Greenwood), Sarah Payson Willis (1811-1872) became the highest-paid newspaper writer in America. By 1854 she was receiving $100 for each column in the New York Ledger, and collected editions of her works such as Fern Leaves from Fanny’s Port-folio (1853) were runaway bestsellers. She would continue to publish acclaimed and popular journalism, along with novels and children’s stories, for the next two decades until her death from cancer in October 1872.

Fern’s career successes speak for themselves, and make her one of the 19th century’s most significant writers and a voice well worth remembering and reading in the 21st century. But there are a number of additional, inspiring layers to her career and life, aspects that go beyond the salary and sales and truly establish Sara Payson Willis as an icon of women’s writing and rights worth celebrating for Women’s History Month.

For one thing, Willis had overcome a number of personal challenges and tragedies in order to get to that 1850s moment of success. Her first marriage, to Boston banker Charles Harrington Eldredge, ended after nine years with his 1846 death, the last in a string of tragedies between 1844 and 1846 that included the death of their oldest daughter Mary and of Willis’s younger sister Ellen. Widowed with two surviving daughters, and receiving virtually no support from her family, Willis remarried Samuel Farrington, a Boston merchant who turned out to be a jealous and abusive husband. In 1851, after only two years of marriage, Willis and her daughters moved out, choosing to live in a hotel and endure numerous rumors spread by Farrington rather than put up with his abuse.

The lack of support from her family throughout this time extended beyond financial. Willis’s brother Nathaniel Parker Willis was a prominent literary figure and editor, and had begun his own successful publication, the Home Journal. Yet he refused to support or publish his sister’s writing, and when his young editor James Parton reprinted some of her columns, Willis forbade him to do so, forcing Parton to quit in protest. These and other incidents, along with the tragedies and struggles of her first two marriages, became central threads in Ruth Hall: A Domestic Tale of the Present Time (1854), the autobiographical novel through which Fern found a way to have her say in response to Nathaniel, her family, the Boston literary scene, and the vicissitudes of life.

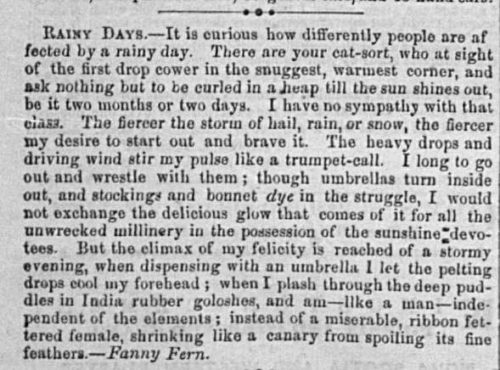

Fern also used her daily columns to highlight, satirize, and challenge the kinds of social norms and prejudices that limited and oppressed mid-19th century American women. “Hungry Husbands” (1857) uses a witty, sly examination of domestic gender roles to raise the specter of domestic abuse. “A Law More Nice Than Just” (1858) highlights the case of a woman arrested for wearing men’s clothes, with Fern performing her own experimental, illegal walk in men’s garments with the aid of her supportive third husband (none other than James Parton!). And “Male Criticism on Ladies’ Books” (1857) takes to task and turns on its head the stereotypes and dismissals with which the literary establishment all too often treated writers like Fern.

While such witty and sarcastic pieces were Fern’s stock-in-trade, she was also more than capable of producing thoughtful investigative journalism that examined other sides of women’s experiences and identities in her society. Exemplifying that genre was her multi-part 1858 series on Blackwell’s Island, the women’s prison (primarily for prostitutes, although that category often simply meant extremely poor, mentally unstable, or other marginalized women) located in New York Harbor. Already the nation’s highest-paid columnist at this time, Fern uses some of that literary capital to bring her audience with her out to Blackwell’s, and to take a long, imperfect but important look at the forgotten women housed in that fraught space.

Reading Fanny Fern today introduces us to a unique and original writer and voice, helps us understand some of the social and historical issues facing mid-19th century women, and offers an inspiring reminder of how our strongest figures have transcended such challenges to create powerful and enduring literary and cultural works. I can think of no better combination of effects with which to celebrate Women’s History Month.