Fidel Castro: The Last Cold Warrior

With the death of Fidel Castro, the Cold War truly passes into history.

All of the other protagonists in the mid-century conflict between communism and democracy are long gone — Kennedy, Khrushchev, Johnson, Brezhnev, Nixon, Mao. Only Castro remained, holding onto life and, until 2006, power over Cuba.

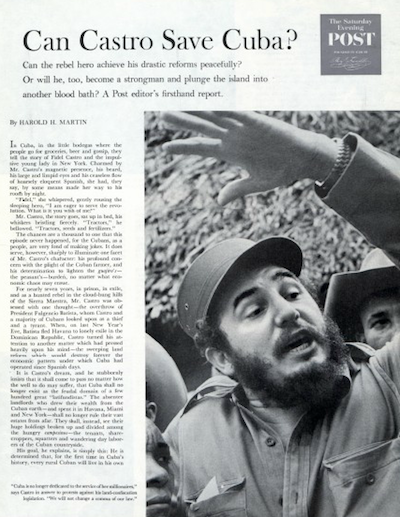

When Castro took control of the Cuban government in 1959, many in the U.S. hoped he would end the decades of corruption by his predecessors. That hope is reflected in Harold Martin’s 1959 article, “Can Castro Save Cuba?,” which was written at a time when Castro was still asserting he was not a communist.

August 1, 1959

But by December of ’59, the tide had shifted away from the sentiment that “anyone who opposes a dictatorship must be our man.” Castro’s animosity toward the U.S. and close ties to Communism rose to the fore, and a Post editorial declared “Fidel Looks Less Like a Friend of the U.S.A. All the Time.”

December 19, 1959

By 1960, Castro had extended recognition to several Marxist-Leninist governments, entered into trade agreements with the Soviets, and nationalized Cuba’s oil refineries, which had been under U.S. control.

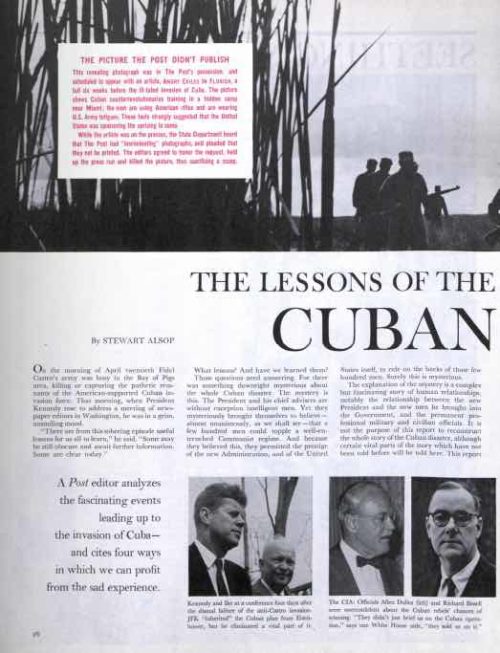

In January, the U.S. cut its diplomatic ties to Cuba and began to fund anti-Castro groups. In 1961, it backed an invasion by Cuban exiles. The swift defeat of the U.S.-funded forces at The Bay of Pigs boosted Castro’s reputation in Central and South America, where he was seen as a champion of Latin American nations against the powerful U.S.

June 24, 1961

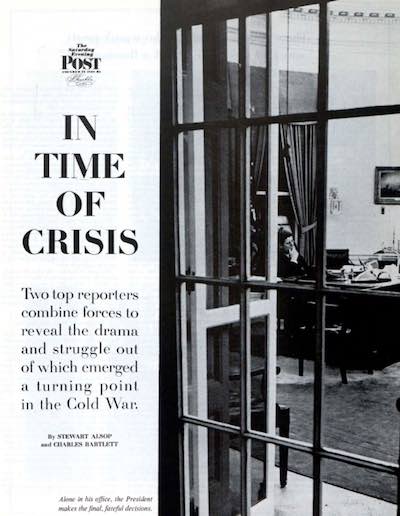

In 1962, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev obtained Castro’s permission to install Soviet-made missiles in Cuba. The move was intended to counterbalance the NATO forces pointed at the Soviet Union. The U.S. demanded the missiles be withdrawn and set up a blockade around the island. It was the closest that the U.S. and Russia came to going to war. Ultimately, the Russians negotiated a withdrawal with the Americans. Stewart Alsop and Charles Bartlett wrote a detailed account in their 1962 article, “In Time of Crisis,” which focuses on lesser-known but ultimately critical episodes. While there were many players, decisions ultimately fell to President Kennedy. The authors note the evident strain on the president:

John F. Kennedy is not an outwardly emotional man, and in the bad days there were few signs that he was passing through the loneliest moments of his lonely job. Once he astonished his wife when he called her at midday and asked her to join him for a walk. Another time he insisted, uncharacteristically, that the children be brought back from Virginia to join him in the White House. But he never lost his sense of humor. On the Sunday of Khrushchev’s big blink, he made a wry remark to his brother Bobby: “Perhaps this is the night I should go to the theater.” No doubt he had Ford’s Theater in mind.

December 8, 1962

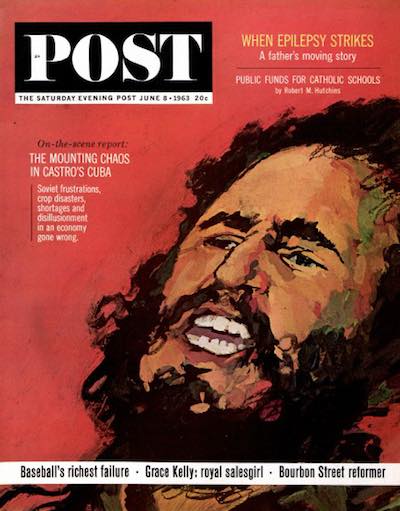

Castro was left out of the negotiations, but he was still regarded by many Americans as a significant threat to the U.S. His policies earned him enemies not only in America but also in Cuba itself. Edward Behr’s article “Chaos in Castro’s Cuba,” presented the Marxist-Leninist government as failing to solve chronic problems of food and employment.

June 8, 1963

Many expected Castro’s government would eventually collapse under the combined pressure of America’s embargo, the moribund economy, and the discontent of Cubans. Of all the surprises of the Cold War, none could match the unexpectedly long life of Castro’s regime, or of Castro himself.

Featured image: Library of Congress