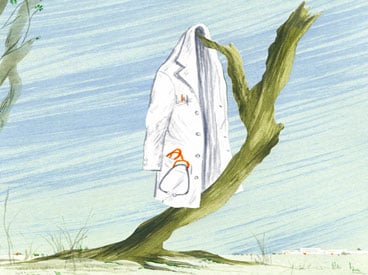

Letting Go

Remember how, in old movies, when someone is dying, the family all gathers around the sick bed and the ailing family member summons his energy to sit up and tell everyone he loves them, then pitches over and goes to his reward? Well, if it was ever like that in real life, it’s not anymore.

In the past 10 years or so, I’ve sat at the bedsides of several friends and family members who have passed on. One week before my mother died at 88, she was ailing but communicative — even cracking jokes — in her hospital bed. But five days later she’d entered “transition,” that purgatory-like state when the body is still alive but the brain has begun shutting down. She was breathing, but unconscious. The nursing staff, knowing the end was near, asked what we wanted to do if her heart stopped. Would we want them to take heroic measures to restart it, very likely breaking her ribs in the process?

No, we said. She was tiny and frail with an intractable condition, and we knew she would not have wanted it. So we sat at her bedside, whispering to her, holding her hand, saying goodbye.

In recent years, the very definition of death has changed, from a precise endpoint to a fuzzy continuum of decline that can be extended artificially for quite some time. And for this, we can thank, or blame, science. My mother got off easy. Some elderly people, well past the point of having even a slender chance of returning to a robust life, become medical pincushions as doctors and nurses see how long they can keep the heart beating.

In “Final Independence,” Jeanne Erdmann describes science’s Faustian bargain unsparingly: “Antibiotics, defibrillators, feeding tubes, and ventilators are lifesaving tools that sometimes become weapons to prolong life against our will.”

How much suffering should a person have to put up with at life’s end? There are advance directives that are supposed to protect you from needless suffering, but as Erdmann points out, it’s all too easy for those wishes to be ignored. We should never forget that medical professionals are trained to cure, not to ease their patients’ passage. Moreover, in today’s litigious world, many doctors are fearful of being sued for negligence. All it takes is one family member arguing that a life-saving procedure was inappropriately withheld.

It’s time for courts to protect doctors who, with family support, agree to mercifully withhold treatment. It’s time for medical schools to develop curricula to help the next generation of doctors learn how to say “this is the end” when the outlook is hopeless. It’s time to help dying patients and their families get through this most difficult part of life’s journey with the least amount of suffering.