The Rise and Fall of Working Women

“Title seven is an unrealistic law.” That’s what an unnamed male corporate executive claimed 50 years ago to a Post reporter when asked about hiring and promoting more women. In 1968, the Civil Rights Act had been federal law for four years, but the tangible results of Title VII’s prohibition of employment discrimination were not cutting it for women workers.

Of the 2,200,000 American earners of more than $10,000 a year in 1968, only 2.5 percent were women, according to Marilyn Mercer’s “Is There Room at the Top?,” published in this magazine. The reasons for the disparity were thought to be systemic and, perhaps, insurmountable. They included outright discrimination, subtle biases, and even a lack of ambition from women themselves.

Mercer found that while almost half of American women were working, they were finding it difficult to advance their careers the same way men could. “Full integration of women into business would mean, ultimately, changing some of our most deep-rooted ideas about sexual roles,” she opined, “And this is something that has never happened before in the civilized — or uncivilized — world.”

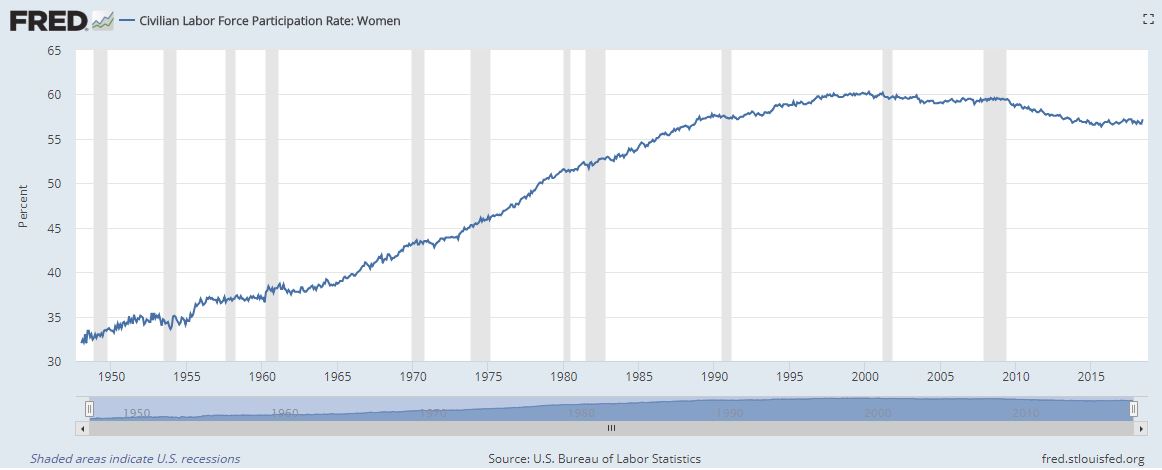

Throughout the decades to come, more and more women joined the white-collar workforce each year. The 1980s and ’90s were characterized by powerful women, from Margaret Thatcher and Oprah Winfrey to fictional women like Murphy Brown and Tess McGill in Working Girl. A cultural urgency for equality saw women donning power suits and going to work. The female labor force participation rate rose to 60 percent by the end of the ’90s, having started at around 30 percent after World War II.

Starting in 2000, however, the tides changed. The percentage of women in the labor force began to drop, and the numbers are now down to that of 1990. The reasons for the lapse in working women aren’t clear, since men have seen the same trend for years. An aging population, an economic recession, and rising enrollment in secondary and postsecondary education could all be factors, according to an economic brief from the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond. The gender wage gap has also remained stagnant, instead of narrowing as it did in those years of growth.

Women in the U.S. have been taking more management positions. Most of the 4.5 million management positions created since 1980 have gone to women, but those gains have been concentrated in fields focused on people as opposed to production. Even more alarming is that as women claim the majority of any management field (like health services, education, and human resources), the gender wage gap of that field increases. The opposite effect occurred in 1980. In the makeup of CEOs and public administrators, the percentage of women has increased only one percent, and, just this year, the number of female CEOs in the Fortune 500 dropped by 25 percent.

The current obstacles to women workers in America are frequently discussed (sexual harassment, lack of paid maternity leave, unconscious bias), and — though a decades-long reexamining of gender roles has led to some progress — there still exists a more than 20 percent wage gap between men’s and women’s earnings.

Mercer’s 1968 look at gender inequality is a deep dive into the sexual psychology behind the American workplace at a time of cultural upheaval and The Feminine Mystique. Despite the disappointing state of female labor, the Post writer found plenty of women executives to celebrate. Katharine Graham had been leading The Washington Post Company for years with excellent results, and Sue Boltz had grown the Detroit industrial firm Goddard & Goddard by millions. In the current era of similar watershed women’s movements and gender revolution, Mercer’s work illuminates the fight for employment equality reaching back over 50 years.