Considering History: Remembering the Founding Fathers, Flaws and All, on the Fourth of July

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

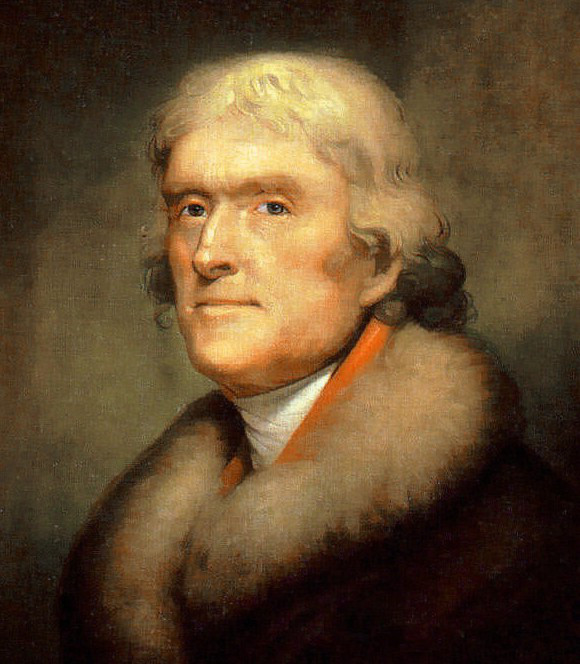

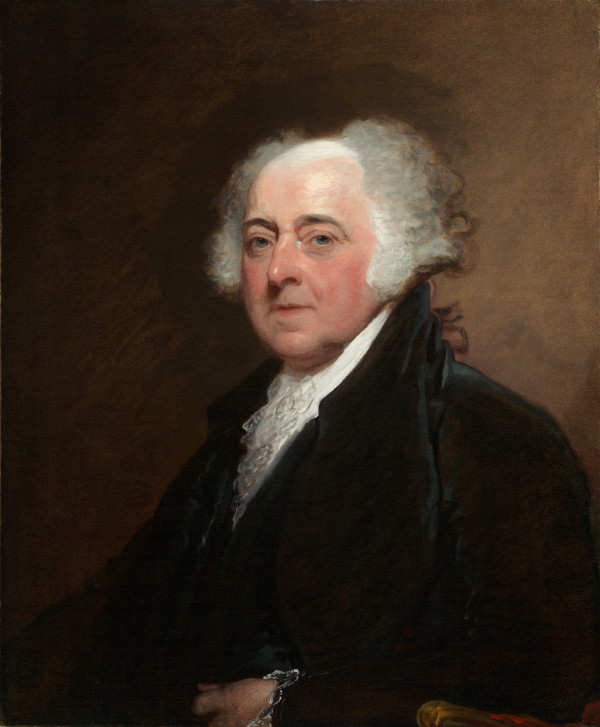

On July 4, 1826, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, America’s second and third presidents and two of the most famous and influential founding fathers, passed away within a few hours of each other. More than just a striking historical fact and one final interconnection between two friends and rivals whose lives and careers had often intertwined, Adams and Jefferson’s July 4 deaths offer a succinct illustration of how much the founders had already become, half a century after the Declaration of Independence, mythic figures with larger-than-life identities and stories.

Those myths are not without merit: the Declaration, Revolution, and Constitution were bold and impressive achievements, and a core group of figures played significant roles in all of them. As I argued in last year’s July 4 article, however, the Declaration also contains a hidden history that reflects darker and more divisive Revolutionary realities of slavery and hypocrisy. Similarly, founders like Adams and Jefferson were complex men, multi-layered historical figures whose flaws as well as their successes have a great deal to teach us about their period and America.

Jefferson’s worst failings are well known, and indeed have come to be defining aspects of our collective memories of him. Yet those flaws go deeper than the alleged (and historically likely, per both uncovered DNA evidence and the vital work of scholar Annette Gordon-Reed) repeated sexual assaults on one of his slaves, Sally Hemings. They also entail racist views of African Americans that become even more hypocritical when seen in light of those personal actions — views illustrated by the cut Declaration paragraph on slavery and the “foreign people” it had “obtruded upon” the colonists, but developed at much greater length in his Notes on the State of Virginia (1785).

In one especially striking extended passage from Notes, Jefferson expounds at length on all the factors that make “the blacks … inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.” He remarks upon their “very strong and disagreeable odor,” their “want of forethought” and “transient griefs,” and their imaginations that are “dull, tasteless, and anomalous.” And he concludes, with particular hypocrisy for a lifelong slaveowner, that “This unfortunate difference of color, and perhaps of faculty, is a powerful obstacle to the emancipation of these people.” While that “perhaps of faculty” indicates an attempt at scientific nuance, the passage as a whole reflects a man unable or unwilling to learn the human truths of the enslaved African Americans all around him.

When it comes to John Adams’s flaws, there’s a general sense that he was one of the most elitist of the founders, a die-hard Federalist who at times feared the general public and its potential for disorder and sedition more than he sought to protect them in our framing documents. That’s a simplified but not inaccurate description of Adams’s overall political philosophies, yet I would argue that it hides a deeper flaw: as his impassioned legal defense of the British soldiers accused of murder at the 1770 Boston Massacre reveals, Adams’s elitism was also racially and culturally charged.

Defending the soldiers was Adams’s job as a young Boston lawyer, and one that he performed with fervor, particularly in an eloquent court monologue that helped win an acquittal for many of the accused. In the course of that statement, Adams deployed a series of stereotypical and bigoted images of the massacre’s first victim, Crispus Attucks. Attucks, Adams argued, had “undertaken to be the hero of the night” through his “mad behavior,” but exemplified instead the event’s “motley rabble of saucy boys, negroes and mulattos, Irish teagues and outlandish jack tars.” Given that Attucks was not only a mixed-race individual but also a fugitive slave, Adams’s language reveals the links between Revolutionary elitism and the same kinds of racist hypocrisy embodied by Jefferson.

So these famous founders weren’t just flawed — they were flawed in ways that reveal some of the exclusionary, white supremacist elements of the nation’s origins. Their vision of who was American — or at least who was most fully and definingly American—was certainly part of the Revolutionary era, and has continued to echo ever since. But it’s not the only side of the era, nor of these men and their lives and legacies. There are also genuinely inspiring sides to both Adams and Jefferson that embody our nation at its best.

Some of Adams’s most inspiring moments are directly tied to his marriage, and through them to his wife, the deeply impressive historical figure Abigail Smith Adams. Thanks to the work of historian Sara Georgini and the entire Adams Family Papers staff at the Massachusetts Historical Society, we have unparalleled access to materials like John Adams’s letters, many of which were exchanged with Abigail as the two were separated for more than a decade before, during, and after the events of the Revolution.

Those letters are justifiably famous for striking individual moments: John’s eerily accurate July 1776 predictions about future Independence Day celebrations; Abigail’s March 1776 letter imploring her husband and his fellow framers to “Remember the ladies” in their deliberations. But what the letters as a whole reveal more deeply are the sacrifices made by the founders during their decades of service to the nation for which they were fighting. That’s especially clear in an emotional July 1776 letter when John, having learned that his family had been suffering from smallpox without his knowledge, writes,

Do my Friends think that I have been a Politician so long as to have lost all feeling? Do they suppose I have forgotten my Wife and Children? … Or have they forgotten that you have a Husband and your Children a Father? What have I done, or omitted to do, that I should be thus forgotten and neglected in the most tender and affecting scene of my Life! Don’t mistake me, I don’t blame you. Your Time and Thoughts must have been wholly taken up, with your own and your Family’s situation and Necessities. But twenty other Persons might have informed me.

Thomas Jefferson had many important and influential moments throughout the Revolution as well as during its aftermath; he drafted the Declaration of Independence and served two terms as president. But to my mind it’s his philosophical, legal, and intellectual work over those same decades that offers his most inspiring contributions to that new America.

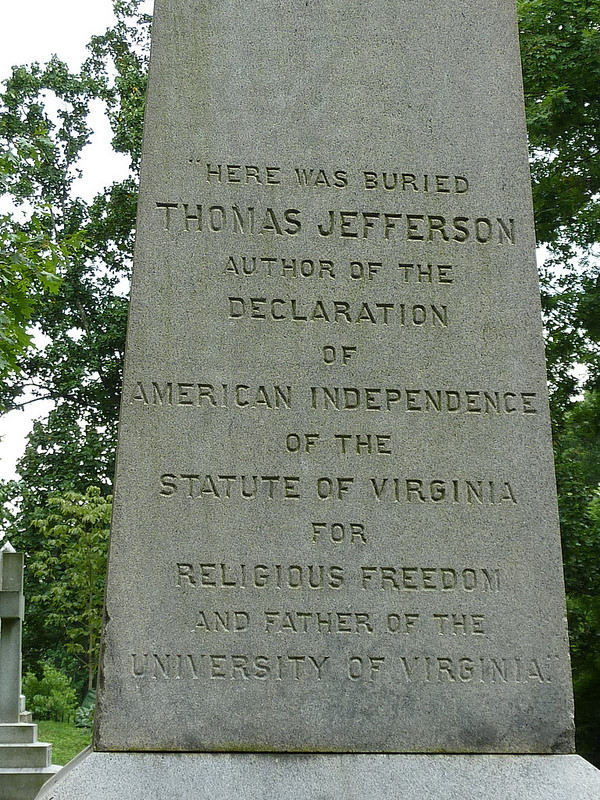

Exemplifying that vital work was Jefferson’s drafting of the 1786 Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom. This law, a key predecessor to the First Amendment’s protections of religious freedom, guaranteed that all Virginians “shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.” Jefferson put that philosophy in action through his professed support for Islam and Muslim Americans as part of these new civic communities. And a few decades later he created a community where such religious and intellectual freedom could flourish, founding the nation’s first non-sectarian public university, the University of Virginia, in 1819.

Jefferson wanted both the statute and the university memorialized on his tombstone (along with the Declaration), a moving illustration that as of July 4, 1826, such civic contributions remained critically important. The two towering figures who died that day left legacies that include some of America’s more divisive and bigoted histories to be sure. But they also contributed, through their lives and their ideas, to the founding of American ideals as well as the nation. Critical patriotism requires us to remember all these sides to Adams, Jefferson, and America on the Fourth of July.

Featured image: John Adams and Thomas Jefferson (Detail from postcard published by The Foundation Press, Inc., 1932. Reproduction of oil painting from the artist’s series: The Pageant of a Nation. Collection of the Virginia Historical Society, Library of Congress)