“A Friend of Napoleon” by Richard Connell

Author of the widely-read short story “The Most Dangerous Game,” Richard Connell wrote fiction, screenplays, and more in the early 20th century. His O. Henry Prize story “A Friend of Napoleon” follows a well-meaning wax museum night guard in a farcical romp of crime and romance.

Published on June 30, 1923

All Paris held no happier man than Papa Chibou. He loved his work — that was why. Other men might say — did say, in fact — that for no amount of money would they take his job; no, not for ten thousand francs for a single night. It would turn their hair white and give them permanent goose flesh, they averred. On such men Papa Chibou smiled with pity. What stomach had such zestless ones for adventure? What did they know of romance? Every night of his life Papa Chibou walked with adventure and held the hand of romance.

Every night he conversed intimately with Napoleon; with Marat and his fellow revolutionists; with Carpentier and Caesar; with Victor Hugo and Lloyd George; with Foch and with Bigarre, the Apache murderer whose unfortunate penchant for making ladies into curry led him to the guillotine; with Louis XVI and with Madame Lablanche, who poisoned eleven husbands and was working to make it an even dozen when the police deterred her; with Marie Antoinette and with sundry early Christian martyrs who lived in sweet resignation in electric-lighted catacombs under the sidewalk of the Boulevard des Capucines in the very heart of Paris. They were all his friends and he had a word and a joke for each of them as, on his nightly rounds, he washed their faces and dusted out their ears, for Papa Chibou was night watchman at the Museum Pratoucy — “The World in Wax. Admission, one franc. Children and soldiers, half price. Nervous ladies enter the Chamber of Horrors at their own risk. One is prayed not to touch the wax figures or to permit dogs to circulate in the establishment.”

He had been at the Museum Pratoucy so long that he looked like a wax figure himself. Visitors not infrequently mistook h im for one and poked him with inquisitive fingers or canes. He did not undeceive them; he did not budge; Spartan-like he stood stiff under the pokes; he was rather proud of being taken for a citizen of the world of wax, which was, indeed, a much more real world to him than the world of flesh and blood. He had cheeks like the small red wax pippins used in table decorations, round eyes, slightly poppy, and smooth white hair, like a wig. He was a diminutive man and, with his horseshoe mustache of surprising luxuriance, looked like a gnome going to a fancy-dress ball as a small walrus. Children who saw him flitting about the dim passages that led to the catacombs were sure he was a brownie.

His title “Papa” was a purely honorary one, given him because he had worked some twenty-five years at the museum. He was unwed, and slept at the museum in a niche of a room just off the Roman arena where papier-mâché lions and tigers breakfasted on assorted martyrs. At night, as he dusted off the lions and tigers, he rebuked them sternly for their lack of delicacy.

“Ah,” he would say, cuffing the ear of the largest lion, which was earnestly trying to devour a grandfather and an infant simultaneously, “sort of a pig that you are! I am ashamed of you, eater of babies. You will go to hell for this, Monsieur Lion, you may depend upon it. Monsieur Satan will poach you like an egg, I promise you. Ah, you bad one, you species of a camel, you Apache, you profiteer —”

Then Papa Chibou would bend over and very tenderly address the elderly martyr who was lying beneath the lion’s paws and exhibiting signs of distress, and say, “Patience, my brave one. It does not take long to be eaten, and then, consider: The good Lord will take you up to heaven, and there, if you wish, you yourself can eat a lion every day. You are a man of holiness, Phillibert. You will be Saint Phillibert, beyond doubt, and then won’t you laugh at lions!”

Phillibert was the name Papa Chibou had given to the venerable martyr; he had bestowed names on all of them. Having consoled Phillibert, he would softly dust the fat wax infant whom the lion was in the act of bolting.

“Courage, my poor little Jacob,” Papa Chibou would say. “It is not every baby that can be eaten by a lion; and in such a good cause too. Don’t cry, little Jacob. And remember: When you get inside Monsieur Lion, kick and kick and kick! That will give him a great sickness of the stomach. Won’t that be fun, little Jacob?”

So he went about his work, chatting with them all, for he was fond of them all, even of Bigarre the Apache and the other grisly inmates of the Chamber of Horrors. He did chide the criminals for their regrettable proclivities in the past and warn them that he would tolerate no such conduct in his museum. It was not his museum of course. Its owner was Monsieur Pratoucy, a long-necked, melancholy marabou of a man who sat at the ticket window and took in the francs. But, though the legal title to the place might be vested in Monsieur Pratoucy, at night Papa Chibou was the undisputed monarch of his little wax kingdom. When the last patron had left and the doors were closed Papa Chibou began to pay calls on his subjects; across the silent halls he called greetings to them:

“Ah, Bigarre, you old rascal, how goes the world? And you, Madame Marie Antoinette, did you enjoy a good day? Good evening, Monsieur Caesar; aren’t you chilly in that costume of yours? Ah, Monsieur Charlemagne, I trust your health continues to be of the best.”

His closest friend of them all was Napoleon. The others he liked; to Napoleon he was devoted. It was a friendship cemented by the years, for Napoleon had been in the museum as long as Papa Chibou. Other figures might come and go at the behest of a fickle public, but Napoleon held his place, albeit he had been relegated to a dim corner.

He was not much of a Napoleon. He was smaller even than the original Napoleon, and one of his ears had come in contact with a steam radiator and as a result it was gnarled into a lump the size of a hickory nut; it was a perfect example of that phenomenon of the prize ring, the cauliflower ear. He was supposed to be at St. Helena and he stood on a papier-mâché rock, gazing out wistfully over a nonexistent sea. One hand was thrust into the bosom of his long-tailed coat, the other hung at his side. Skintight breeches, once white but white no longer, fitted snugly over his plump bump of waxen abdomen. A Napoleonic hat, frayed by years of conscientious brushing by Papa Chibou, was perched above a pensive waxen brow.

Papa Chibou had been attracted to Napoleon from the first. There was something so forlorn about him. Papa Chibou had been forlorn, too, in his first days at the museum. He had come from Bouloire, in the south of France, to seek his fortune as a grower of asparagus in Paris. He was a simple man of scant schooling and he had fancied that there were asparagus beds along the Paris boulevards. There were none. So necessity and chance brought him to the Museum Pratoucy to earn his bread and wine, and romance and his friendship for Napoleon kept him there.

The first day Papa Chibou worked at the museum Monsieur Pratoucy took him round to tell him about the figures.

“This,” said the proprietor, “is Toulon, the strangler. This is Mademoiselle Merle, who shot the Russian duke. This is Charlotte Corday, who stabbed Marat in the bathtub; that gory gentleman is Marat.” Then they had come to Napoleon. Monsieur Pratoucy was passing him by.

“And who is this sad-looking gentleman?” asked Papa Chibou.

“Name of a name! Do you not know?”

“But no, monsieur.”

“But that is Napoleon himself.”

That night, his first in the museum, Papa Chibou went round and said to Napoleon, “Monsieur, I do not know with what crimes you are charged, but I, for one, refuse to think you are guilty of them.”

So began their friendship. Thereafter he dusted Napoleon with especial care and made him his confidant. One night in his twenty-fifth year at the museum Papa Chibou said to Napoleon, “You observed those two lovers who were in here tonight, did you not, my good Napoleon? They thought it was too dark in this corner for us to see, didn’t they? But we saw him take her hand and whisper to her. Did she blush? You were near enough to see. She is pretty, isn’t she, with her bright dark eyes? She is not a French girl; she is an American; one can tell that by the way she doesn’t roll her r’s. The young man, he is French; and a fine young fellow he is, or I’m no judge. He is so slender and erect, and he has courage, for he wears the war cross; you noticed that, didn’t you? He is very much in love, that is sure. This is not the first time I have seen them. They have met here before, and they are wise, for is this not a spot most romantic for the meetings of lovers?”

Papa Chibou flicked a speck of dust from Napoleon’s good ear.

“Ah,” he exclaimed, “it must be a thing most delicious to be young and in love! Were you ever in love, Napoleon? No? Ah, what a pity! I know, for I, too, have had no luck in love. Ladies prefer the big, strong men, don’t they? Well, we must help these two young people, Napoleon. We must see that they have the joy we missed. So do not let them know you are watching them if they come here tomorrow night. I will pretend I do not see.”

Each night after the museum had closed, Papa Chibou gossiped with Napoleon about the progress of the love affair between the American girl with the bright dark eyes and the slender, erect young Frenchman.

“All is not going well,” Papa Chibou reported one night, shaking his head. “There are obstacles to their happiness.

“He has little money, for he is just beginning his career. I heard him tell her so tonight. And she has an aunt who has other plans for her. What a pity if fate should part them! But you know how unfair fate can be, don’t you, Napoleon? If we only had some money we might be able to help him, but I, myself, have no money, and I suppose you, too, were poor, since you look so sad. But attend; tomorrow is a day most important for them. He has asked her if she will marry him, and she has said that she will tell him tomorrow night at nine in this very place. I heard them arrange it all. If she does not come it will mean no. I think we shall see two very happy ones here tomorrow night, eh, Napoleon?”

The next night when the last patron had gone and Papa Chibou had locked the outer door, he came to Napoleon, and tears were in his eyes.

“You saw, my friend?” broke out Papa Chibou. “You observed? You saw his face and how pale it grew? You saw his eyes and how they held a thousand agonies? He waited until I had to tell him three times that the museum was closing. I felt like an executioner, I assure you; and he looked up at me as only a man condemned can look. He went out with heavy feet; he was no longer erect. For she did not come, Napoleon; that girl with the bright dark eyes did not come. Our little comedy of love has become a tragedy, monsieur. She has refused him, that poor, that unhappy young man.”

On the following night at closing time Papa Chibou came hurrying to Napoleon; he was a-quiver with excitement.

“She was here!” he cried. “Did you see her? She was here and she kept watching and watching; but, of course, he did not come. I could tell from his stricken face last night that he had no hope. At last I dared to speak to her. I said to her, ‘Mademoiselle, a thousand pardons for the very great liberty I am taking, but it is my duty to tell you — he was here last night and he waited till closing time. He was all of a paleness, mademoiselle, and he chewed his fingers in his despair. He loves you, mademoiselle; a cow could see that. He is devoted to you; and he is a fine young fellow, you can take an old man’s word for it. Do not break his heart, mademoiselle.’ She grasped my sleeve. ‘You know him, then?’ she asked. ‘You know where I can find him?’ ‘Alas, no,’ I said. ‘I have only seen him here with you.’ ‘Poor boy!’ she kept saying. ‘Poor boy! Oh, what shall I do? I am in dire trouble. I love him, monsieur.’ ‘But you did not come,’ I said. ‘I could not.’ she replied, and she was weeping. ‘I live with an aunt; a rich tiger she is, monsieur, and she wants me to marry a count, a fat leering fellow who smells of attar of roses and garlic. My aunt locked me in my room. And now I have lost the one I love, for he will think I have refused him, and he is so proud he will never ask me again.’ ‘But surely you could let him know?’ I suggested. ‘But I do not know where he lives,’ she said. ‘And in a few days my aunt is taking me off to Rome, where the count is, and oh, dear, oh, dear, oh, dear — ’ And she wept on my shoulder, Napoleon, that poor little American girl with the bright dark eyes.”

Papa Chibou began to brush the Napoleonic hat.

“I tried to comfort her,” he said. “I told her that the young man would surely find her, that he would come back and haunt the spot where they had been happy, but I was telling her what I did not believe. ‘He may come tonight,’ I said, ‘or tomorrow.’ She waited until it was time to close the museum. You saw her face as she left; did it not touch you in the heart?”

Papa Chibou was downcast when he approached Napoleon the next night.

“She waited again till closing time,” he said, “but he did not come. It made me suffer to see her as the hours went by and her hope ebbed away. At last she had to leave, and at the door she said to me, ‘If you see him here again, please give him this.’ She handed me this card, Napoleon. See, it says, ‘I am at the Villa Rosina, Rome. I love you. Nina.’ Ah, the poor, poor young man. We must keep a sharp watch for him, you and I.”

Papa Chibou and Napoleon did watch at the Museum Pratoucy night after night. One, two, three, four, five nights they watched for him. A week, a month, more months passed, and he did not come. There came instead one day news of so terrible a nature that it left Papa Chibou ill and trembling. The Museum Pratoucy was going to have to close its doors.

“It is no use,” said Monsieur Pratoucy, when he dealt this blow to Papa Chibou. “I cannot go on. Already I owe much, and my creditors are clamoring. People will no longer pay a franc to see a few old dummies when they can see an army of red Indians, Arabs, brigands and dukes in the moving pictures. Monday the Museum Pratoucy closes its doors forever.”

“But, Monsieur Pratoucy,” exclaimed Papa Chibou, aghast, “what about the people here? What will become of Marie Antoinette, and the martyrs and Napoleon?”

“Oh,” said the proprietor, “I’ll be able to realize a little on them perhaps. On Tuesday they will be sold at auction. Someone may buy them to melt up.”

“To melt up, monsieur?” Papa Chibou faltered.

“But certainly. What else are they good for?”

“But surely monsieur will want to keep them; a few of them anyhow?”

“Keep them? Aunt of the devil, but that is a droll idea! Why should anyone want to keep shabby old wax dummies?”

“I thought,” murmured Papa Chibou, “that you might keep just one — Napoleon, for example — as a remembrance — ”

“Uncle of Satan, but you have odd notions! To keep a souvenir of one’s bankruptcy!”

Papa Chibou went away to his little hole in the wall. He sat on his cot and fingered his mustache for an hour; the news had left him dizzy, had made a cold vacuum under his belt buckle. From under his cot, at last, he took a wooden box, unlocked three separate locks and extracted a sock. From the sock he took his fortune, his hoard of big copper ten-centime pieces, tips he had saved for years. He counted them over five times most carefully; but no matter how he counted them he could not make the total come to more than two hundred and twenty-one francs.

That night he did not tell Napoleon the news. He did not tell any of them. Indeed he acted even more cheerful than usual as he went from one figure to another. He complimented Madame Lablanche, the lady of the poisoned spouses, on how well she was looking. He even had a kindly word to say to the lion that was eating the two martyrs.

“After all, Monsieur Lion,” he said, “I suppose it is as proper for you to eat martyrs as it is for me to eat bananas. Probably bananas do not enjoy being eaten any more than martyrs do. In the past I have said harsh things to you, Monsieur Lion; I am sorry I said them, now. After all, it is hardly your fault that you eat people. You were born with an appetite for martyrs, just as I was born poor.” And he gently tweaked the lion’s papier-mâché ear.

When he came to Napoleon, Papa Chibou brushed him with unusual care and thoroughness. With a moistened cloth he polished the imperial nose, and he took pains to be gentle with the cauliflower ear. He told Napoleon the latest joke he had heard at the cabmen’s café where he ate his breakfast of onion soup, and, as the joke was mildly improper, nudged Napoleon in the ribs, and winked at him.

“We are men of the world, eh, old friend?” said Papa Chibou. “We are philosophers, is that not so?” Then he added, “We take what life sends us, and sometimes it sends hardnesses.”

He wanted to talk more with Napoleon, but somehow he couldn’t; abruptly, in the midst of a joke, Papa Chibou broke off and hurried down into the depths of the Chamber of Horrors and stood there for a very long time staring at an unfortunate native of Siam being trodden on by an elephant.

It was not until the morning of the auction sale that Papa Chibou told Napoleon. Then, while the crowd was gathering, he slipped up to Napoleon in his corner and laid his hand on Napoleon’s arm.

“One of the hardnesses of life has come to us, old friend,” he said. “They are going to try to take you away. But, courage! Papa Chibou does not desert his friends. Listen!” And Papa Chibou patted his pocket, which gave forth a jingling sound.

The bidding began. Close to the auctioneer’s desk stood a man, a wizened, rodent-eyed man with a diamond ring and dirty fingers. Papa Chibou’s heart went down like an express elevator when he saw him, for he knew that the rodent-eyed man was Mogen, the junk king of Paris. The auctioneer, in a voice slightly encumbered by adenoids, began to sell the various items in a hurried, perfunctory manner.

“Item 3 is Julius Caesar, toga and sandals thrown in. How much am I offered? One hundred and fifty francs? Dirt cheap for a Roman emperor, that is. Who’ll make it two hundred? Thank you, Monsieur Mogen. The noblest Roman of them all is going at two hundred francs. Are you all through at two hundred? Going, going, gone! Julius Caesar is sold to Monsieur Mogen.”

Papa Chibou patted Caesar’s back sympathetically.

“You are worth more, my good Julius,” he said in a whisper. “Good-by.”

He was encouraged. If a comparatively new Caesar brought only two hundred, surely an old Napoleon would bring no more.

The sale progressed rapidly. Monsieur Mogen bought the entire Chamber of Horrors. He bought Marie Antoinette, and the martyrs and lions. Papa Chibou, standing near Napoleon, withstood the strain of waiting by chewing his mustache.

The sale was very nearly over and Monsieur Mogen had bought every item, when, with a yawn, the auctioneer droned: “Now, ladies and gentlemen, we come to Item 573, a collection of odds and ends, mostly damaged goods, to be sold in one lot. The lot includes one stuffed owl that seems to have molted a bit; one Spanish shawl, torn; the head of an Apache who has been guillotined, body missing; a small wax camel, no humps; and an old wax figure of Napoleon, with one ear damaged. What am I offered for the lot?”

Papa Chibou’s heart stood still. He laid a reassuring hand on Napoleon’s shoulder. “The fool,” he whispered in Napoleon’s good ear, “to put you in the same class as a camel, no humps, and an owl. But never mind. It is lucky for us, perhaps.”

“How much for this assortment?” asked the auctioneer.

“One hundred francs,” said Mogen, the junk king.

“One hundred and fifty,” said Papa Chibou, trying to be calm. He had never spent so vast a sum all at once in his life.

Mogen fingered the material in Napoleon’s coat.

“Two hundred,” said the junk king.

“Are you all through at two hundred?” queried the auctioneer.

“Two hundred and twenty-one,” called Papa Chibou. His voice was a husky squeak.

Mogen from his rodent eyes glared at Papa Chibou with annoyance and contempt. He raised his dirtiest finger — the one with the diamond ring on it — toward the auctioneer.

“Monsieur Mogen bids two hundred and twenty-five,” droned the auctioneer. “Do I hear two hundred and fifty?”

Papa Chibou hated the world. The auctioneer cast a look his direction.

“Two hundred and twenty-five is bid,” he repeated. “Are you all through at two hundred and twenty-five? Going, going — sold to Monsieur Mogen for two hundred and twenty-five francs.”

Stunned, Papa Chibou heard Mogen say casually, “I’ll send round my carts for this stuff in the morning.”

This stuff!

Dully and with an aching breast Papa Chibou went to his room down by the Roman arena. He packed his few clothes into a box. Last of all he slowly took from his cap the brass badge he had worn for so many years; it bore the words “Chief Watchman.” He had been proud of that title, even if it was slightly inaccurate; he had been not only the chief but the only watchman. Now he was nothing. It was hours before he summoned up the energy to take his box round to the room he had rented high up under the roof of a tenement in a nearby alley. He knew he should start to look for another job at once, but he could not force himself to do so that day. Instead, he stole back to the deserted museum and sat down on a bench by the side of Napoleon. Silently he sat there all night; but he did not sleep; he was thinking, and the thought that kept pecking at his brain was to him a shocking one. At last, as day began to edge its pale way through the dusty windows of the museum, Papa Chibou stood up with the air of a man who has been through a mental struggle and has made up his mind.

“Napoleon,” he said, “we have been friends for a quarter of a century and now we are to be separated because a stranger had four francs more than I had. That may be lawful, my old friend, but it is not justice. You and I, we are not going to be parted.”

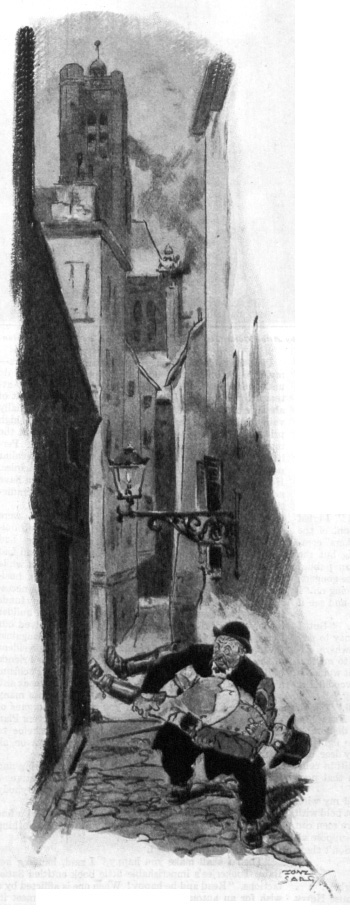

Paris was not yet awake when Papa Chibou stole with infinite caution into the narrow street beside the museum. Along this street toward the tenement where he had taken a room crept Papa Chibou. Sometimes he had to pause for breath, for in his arms he was carrying Napoleon.

Two policemen came to arrest Papa Chibou that very afternoon. Mogen had missed Napoleon, and he was a shrewd man. There was not the slightest doubt of Papa Chibou’s guilt. There stood Napoleon in the corner of his room, gazing pensively out over the housetops. The police bundled the overwhelmed and confused Papa Chibou into the police patrol, and with him, as damning evidence, Napoleon.

In his cell in the city prison Papa Chibou sat with his spirit caved in. To him jails and judges and justice were terrible and mysterious affairs. He wondered if he would be guillotined; perhaps not, since his long life had been one of blameless conduct; but the least he could expect, he reasoned, was a long sentence to hard labor on Devil’s Island, and guillotining had certain advantages over that. Perhaps it would be better to be guillotined, he told himself, now that Napoleon was sure to be melted up.

The keeper who brought him his meal of stew was a pessimist of jocular tendencies.

“A pretty pickle,” said the keeper; “and at your age too. You must be a very wicked old man to go about stealing dummies. What will be safe now? One may expect to find the Eiffel Tower missing any morning. Dummy stealing! What a career! We have had a man in here who stole a trolley car, and one who made off with the anchor of a steamship, and even one who pilfered a hippopotamus from a zoo, but never one who stole a dummy — and an old one-eared dummy, at that! It is an affair extraordinary!”

“And what did they do to the gentleman who stole the hippopotamus?” inquired Papa Chibou tremulously.

The keeper scratched his head to indicate thought.

“I think,” he said, “that they boiled him alive. Either that or they transported him for life to Morocco; I don’t recall exactly.”

Papa Chibou’s brow grew damp.

“It was a trial most comical, I can assure you,” went on the keeper. “The judges were Messieurs Bertouf, Goblin and Perouse — very amusing fellows, all three of them. They had fun with the prisoner; how I laughed. Judge Bertouf said, in sentencing him, ‘We must be severe with you, pilferer of hippopotamuses. We must make of you an example. This business of hippopotamus pilfering is getting all too common in Paris.’ They are witty fellows, those judges.”

Papa Chibou grew a shade paler.

“The Terrible Trio?” he asked.

“The Terrible Trio,” replied the keeper cheerfully.

“Will they be my judges?” asked Papa Chibou.

“Most assuredly,” promised the keeper, and strolled away humming happily and rattling his big keys.

Papa Chibou knew then that there was no hope for him. Even into the Museum Pratoucy the reputation of those three judges had penetrated, and it was a sinister reputation indeed. They were three ancient, grim men who had fairly earned their title, The Terrible Trio, by the severity of their sentences; evildoers blanched at their names, and this was a matter of pride to them.

Shortly the keeper came back; he was grinning.

“You have the devil’s own luck, old-timer,” he said to Papa Chibou. “First you have to be tried by The Terrible Trio, and then you get assigned to you as lawyer none other than Monsieur Georges Dufayel.”

“And this Monsieur Dufayel, is he then not a good lawyer?” questioned Papa Chibou miserably.

The keeper snickered.

“He has not won a case for months,” he answered, as if it were the most amusing thing imaginable. “It is really better than a circus to hear him muddling up his clients’ affairs in court. His mind is not on the case at all. Heaven knows where it is. When he rises to plead before the judges he has no fire, no passion. He mumbles and stutters. It is a saying about the courts that one is as good as convicted who has the ill luck to draw Monsieur Georges Dufayel as his advocate. Still, if one is too poor to pay for a lawyer, one must take what he can get. That’s philosophy, eh, old-timer?”

Papa Chibou groaned.

“Oh, wait till tomorrow,” said the keeper gayly. “Then you’ll have a real reason to groan.”

“But surely I can see this Monsieur Dufayel.”

“Oh, what’s the use? You stole the dummy, didn’t you? It will be there in court to appear against you. How entertaining! Witness for the prosecution: Monsieur Napoleon. You are plainly as guilty as Cain, old-timer, and the judges will boil your cabbage for you very quickly and neatly, I can promise you that. Well, see you tomorrow. Sleep well.”

Papa Chibou did not sleep well. He did not sleep at all, in fact, and when they marched him into the inclosure where sat the other nondescript offenders against the law he was shaken and utterly wretched. He was overawed by the great court room and the thick atmosphere of seriousness that hung over it.

He did pluck up enough courage to ask a guard, “Where is my lawyer, Monsieur Dufayel?”

“Oh, he’s late, as usual,” replied the guard. And then, for he was a waggish fellow, he added, “If you’re lucky he won’t come at all.”

Papa Chibou sank down on the prisoners’ bench and raised his eyes to the tribunal opposite. His very marrow was chilled by the sight of The Terrible Trio. The chief judge, Bertouf, was a vast puff of a man, who swelled out of his judicial chair like a poisonous fungus. His black robe was familiar with spilled brandy, and his dirty judicial bib was askew. His face was bibulous and brutal, and he had the wattles of a turkey gobbler. Judge Goblin, on his right, looked to have mummified; he was at least a hundred years old and had wrinkled parchment skin and red-rimmed eyes that glittered like the eyes of a cobra. Judge Perouse was one vast jungle of tangled grizzled whisker, from the midst of which projected a cockatoo’s beak of a nose; he looked at Papa Chibou and licked his lips with a long pink tongue. Papa Chibou all but fainted; he felt no bigger than a pea, and less important; as for his judges, they seemed enormous monsters.

The first case was called, a young swaggering fellow who had stolen an orange from a pushcart.

“Ah, Monsieur Thief,” rumbled Judge Bertouf with a scowl, “you are jaunty now. Will you be so jaunty a year from today when you are released from prison? I rather think not. Next case.”

Papa Chibou’s heart pumped with difficulty. A year for an orange — and he had stolen a man! His eyes roved round the room and he saw two guards carrying in something which they stood before the judges. It was Napoleon.

A guard tapped Papa Chibou on the shoulder. “You’re next,” he said.

“But my lawyer, Monsieur Dufayel — ” began Papa Chibou.

“You’re in hard luck,” said the guard, “for here he comes.”

Papa Chibou in a daze found himself in the prisoner’s dock. He saw coming toward him a pale young man. Papa Chibou recognized him at once. It was the slender, erect young man of the museum. He was not very erect now; he was listless. He did not recognize Papa Chibou; he barely glanced at him.

“You stole something,” said the young lawyer, and his voice was toneless. “The stolen goods were found in your room. I think we might better plead guilty and get it over with.”

“Yes, monsieur,” said Papa Chibou, for he had let go all his hold on hope. “But attend a moment. I have something — a message for you.”

Papa Chibou fumbled through his pockets and at last found the card of the American girl with the bright dark eyes. He handed it to Georges Dufayel.

“She left it with me to give to you,” said Papa Chibou. “I was chief watchman at the Museum Pratoucy, you know. She came there night after night, to wait for you.”

The young man gripped the sides of the card with both hands; his face, his eyes, everything about him seemed suddenly charged with new life.

“Ten thousand million devils!” he cried. “And I doubted her! I owe you much, monsieur. I owe you everything.” He wrung Papa Chibou’s hand.

Judge Bertouf gave an impatient judicial grunt.

“We are ready to hear your case, Advocate Dufavel,” said the judge, “if you have one.”

The court attendants sniggered.

“A little moment, monsieur the judge,” said the lawyer. He turned to Papa Chibou. “Quick,” he shot out, “tell me about the crime you are charged with. What did you steal?”

“Him,” replied Papa Chibou, pointing.

“That dummy of Napoleon?”

Papa Chibou nodded.

“But why?”

Papa Chibou shrugged his shoulders.

“Monsieur could not understand.”

“But you must tell me!” said the lawyer urgently. “I must make a plea for you. These savages will be severe enough, in any event; but I may be able to do something. Quick; why did you steal this Napoleon?”

“I was his friend,” said Papa Chibou. “The museum failed. They were going to sell Napoleon for junk, Monsieur Dufayel. He was my friend. I could not desert him.”

The eyes of the young advocate had caught fire; they were lit with a flash. He brought his fist down on the table.

“Enough!” he cried.

Then he rose in his place and addressed the court. His voice was low, vibrant and passionate; the judges, in spite of themselves, leaned forward to listen to him.

“May it please the honorable judges of this court of France,” he began, “my client is guilty. Yes, I repeat in a voice of thunder, for all France to hear, for the enemies of France to hear, for the whole wide world to hear, he is guilty. He did steal this figure of Napoleon, the lawful property of another. I do not deny it. This old man, Jerome Chibou, is guilty, and I for one am proud of his guilt.”

Judge Bertouf grunted.

“If your client is guilty, Advocate Dufayel,” he said, “that settles it. Despite your pride in his guilt, which is a peculiar notion, I confess, I am going to sentence him to — ”

“But wait, your honor!” Dufayel’s voice was compelling. “You must, you shall hear me! Before you pass sentence on this old man, let me ask you a question.”

“Well?”

“Are you a Frenchman, Judge Bertouf?”

“But certainly.”

“And you love France?”

“Monsieur has not the effrontery to suggest otherwise?”

“No. I was sure of it. That is why you will listen to me.”

“I listen.”

“I repeat then: Jerome Chibou is guilty. In the law’s eyes he is a criminal. But in the eyes of France and those who love her his guilt is a glorious guilt; his guilt is more honorable than innocence itself.”

The three judges looked at one another blankly; Papa Chibou regarded his lawyer with wide eyes; George Dufayel spoke on.

“These are times of turmoil and change in our country, messieurs the judges. Proud traditions which were once the birthright of every Frenchman have been allowed to decay. Enemies beset us within and without. Youth grows careless of that honor which is the soul of a nation. Youth forgets the priceless heritages of the ages, the great names that once brought glory to France in the past, when Frenchmen were Frenchmen. There are some in France who may have forgotten the respect due a nation’s great” — here Advocate Dufayel looked very hard at the judges — “but there are a few patriots left who have not forgotten. And there sits one of them.

“This poor old man has deep within him a glowing devotion to France. You may say that he is a simple unlettered peasant. You may say that he is a thief. But I say, and true Frenchmen will say with me, that he is a patriot, messieurs the judges. He loves Napoleon. He loves him for what he did for France. He loves him because in Napoleon burned that spirit which has made France great. There was a time, messieurs the judges, when your fathers and mine dared share that love for a great leader. Need I remind you of the career of Napoleon? I know I need not. Need I tell you of his victories? I know I need not.”

Nevertheless Advocate Dufayel did tell them of the career of Napoleon. With a wealth of detail and many gestures he traced the rise of Napoleon; he lingered over his battles; for an hour and ten minutes he spoke eloquently of Napoleon and his part in the history of France.

“You may have forgotten,” he concluded, “and others may have forgotten, but this old man sitting here a prisoner — he did not forget. When mercenary scoundrels wanted to throw on the junk heap this effigy of one of France’s greatest sons, who was it that saved him? Was it you, messieurs the judges? Was it I? Alas, no. It was a poor old man who loved Napoleon more than he loved himself. Consider, messieurs the judges; they were going to throw on the junk heap Napoleon — France’s Napoleon — our Napoleon. Who would save him? Then up rose this man, this Jerome Chibou, whom you would brand as a thief, and he cried aloud for France and for the whole world to hear, ‘Stop! Desecraters of Napoleon, stop! There still lives one Frenchman who loves the memories of his native land; there is still one patriot left. I, I, Jerome Chibou, will save Napoleon!’ And he did save him, messieurs the judges.”

Advocate Dufayel mopped his brow, and leveling an accusing finger at The Terrible Trio he said, “You may send Jerome Chibou to jail. But when you do, remember this: You are sending to jail the spirit of France. You may find Jerome Chibou guilty. But when you do, remember this: You are condemning a man for love of country, for love of France. Wherever true hearts beat in French bosoms, messieurs the judges, there will the crime of Jerome Chibou be understood, and there will the name of Jerome Chibou be honored. Put him in prison, messieurs the judges. Load his poor feeble old body with chains. And a nation will tear down the prison walls, break his chains, and pay homage to the man who loved Napoleon and France so much that he was willing to sacrifice himself on the altar of patriotism.”

Advocate Dufayel sat down; Papa Chibou raised his eyes to the judges’ bench. Judge Perouse was ostentatiously blowing his beak of a nose. Judge Goblin, who wore a Sedan ribbon in his buttonhole, was sniffling into his inkwell. And Chief Judge Bertouf was openly blubbering.

“Jerome Chibou, stand up.” It was Chief Judge Bertouf who spoke, and his voice was thick with emotion.

Papa Chibou, quaking, stood up. A hand like a hand of pink bananas was thrust down at him.

“Jerome Chibou,” said Chief Judge Bertouf, “I find you guilty. Your crime is patriotism in the first degree. I sentence you to freedom. Let me have the honor of shaking the hand of a true Frenchman.”

“And I,” said Judge Goblin, thrusting out a hand as dry as autumn leaves.

“And I also,” said Judge Perouse, reaching out a hairy hand.

“And, furthermore,” said Chief Judge Bertouf, “you shall continue to protect the Napoleon you saved. I subscribe a hundred francs to buy him for you.”

“And I,” said Judge Goblin.

“And I also,” said Judge Perouse.

As they left the court room, Advocate Dufayel, Papa Chibou and Napoleon, Papa Chibou turned to his lawyer.

“I can never repay monsieur,” he began.

“Nonsense!” said the lawyer.

“And would Monsieur Dufayel mind telling me again the last name of Napoleon? “

“Why, Bonaparte, of course. Surely you knew — ”

“Alas, no, Monsieur Dufayel. I am a man the most ignorant. I did not know that my friend had done such great things.”

“You didn’t? Then what in the name of heaven did you think Napoleon was?”

“A sort of murderer,” said Papa Chibou humbly.

Out beyond the walls of Paris in a garden stands the villa of Georges Dufayel, who has become, everyone says, the most eloquent and successful young lawyer in the Paris courts. He lives there with his wife, who has bright dark eyes. To get to his house one must pass a tiny gatehouse, where lives a small old man with a prodigious walrus mustache. Visitors who peer into the gatehouse as they pass sometimes get a shock, for standing in one corner of its only room they see another small man, in uniform and a big hat. He never moves, but stands there by the-window all day, one hand in the bosom of his coat, the other at his side, while his eyes look out over the garden. He is waiting for Papa Chibou to come home after his work among the asparagus beds to tell him the jokes and the news of the day.

Featured image: Illustrated by Tony Sarg; © SEPS.

When We Were Heroes

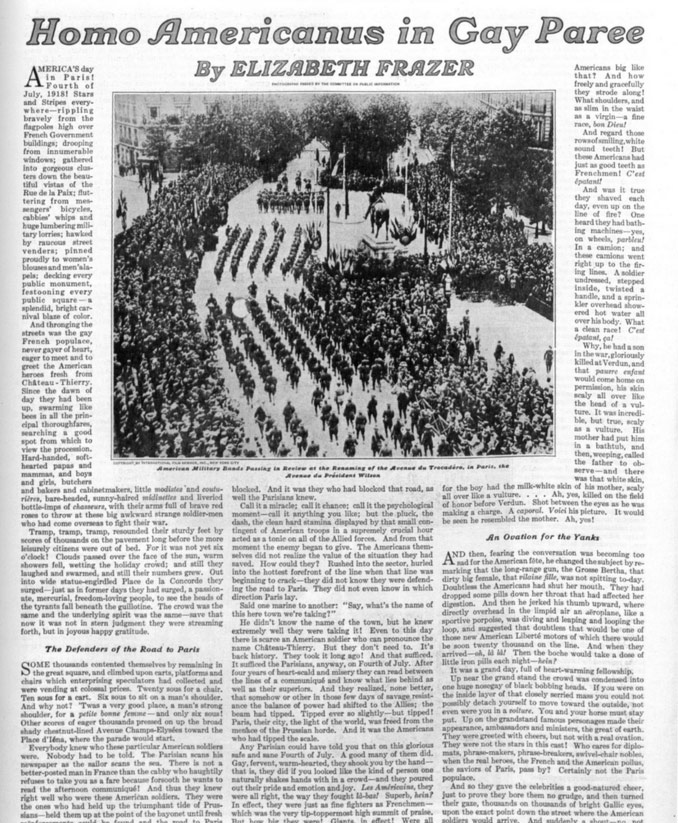

This excerpt is from the article “Homo Americanus in Gay Paree” by Elizabeth Frazer, which appeared in the November 2, 1918, issue of The Saturday Evening Post.

Suddenly a shout — no, not exactly a shout; rather, a big happy hurrah — burst simultaneously from thousands of grateful happy hearts. Here they come! Les Americains! Here they come! Strong emotion swept the crowd like a breeze. Vive l’Amerique! Vive les Americains!

And all that excited sea of souls laughed and cried and shouted and sobbed and rocked in glad exultation over these fine, big, clean garçons who had fought so splendidly, so desperately, so victoriously beside their own brave poilus.

It was American troops who stemmed the tide, who closed the road to Paris. They paid the price in blood, and the price was high. For that single episode showed both friends and foe where the war’s balance of power lay.

On they came, their bayonets glittering in the sun, their faces wreathed in smiles, their eyes — well, not quite straight dead ahead! For who can discipline his eyes, when a bombardment of roses or a barrage of violets hits one straight on the nose? There are garlands of roses round their necks, roses behind their ears, roses in their cartridge belts, roses in the nozzles of their guns, which lately spouted flame and shortly will again.

But today is Fourth of July in Paris! And these soldiers have earned this day of joy.

This article appears in the November/December 2018 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

WWII: What Happened to France

The news from Europe stunned America: On June 22, 1940, France surrendered to Germany.

Just six weeks earlier, Nazi Germany had sent its army into Holland and Belgium. In response, the French army moved north to meet the German advance, and British troops joined the fight. But by June 15, the Germans were marching into Paris. Six days later, the French government signed an armistice with the Nazis.

Americans wondered how this could be. They recalled how during the Great War 25 years earlier, France and Great Britain had stopped an invading German army. The two Allied forces pinned the Germans on a battle line 450 miles long for four years. And despite losing over a million soldiers, France ultimately defeated Germany.

But now, in this new war, Germany’s army pushed Britain’s army all the way back to the English Channel. The British only escaped capture when a hastily assembled fleet of 800 boats withdrew them to England.

Now alone, France struggled on, hoping to avoid the fate of Poland, Norway, Denmark, Luxembourg, Holland, and Belgium. But on June 22, France, too, surrendered to Germany.

In the U.S., the Nazi’s swift victory caused many to reconsider their neutrality. Dismissing the Nazi threat was easy when they presumed France and Great Britain would stop Hitler. But now, with France occupied, one less nation stood between the U.S. and Germany. Great Britain remained defiant and free, but many Americans thought the country had little chance of surviving.

So what had happened to the French?

Post contributor Demaree Bess was in Paris, looking for an explanation. He didn’t find many answers. He didn’t find many Parisians, either. The government fled the capital, along with much of the city’s population. In “With Their Hands in Their Pocket,” Bess describes his days in an eerily empty city awaiting the German conquerors.

Today, you can find several explanations for the French defeat. The most obvious, of course, is the German army, which spent 20 years preparing for the second great war.

When World War I ended, Germany was left with little food, rampant inflation, a government in chaos, and crippling penalties imposed by the Treaty of Versailles. In their grief and anger, many Germans found it easy to believe the myth that Germany had been betrayed by treacherous Germans. As Germans loudly demanded the right to re-arm their nation, the German military began secretly training the next generation of warriors. Given time, training, and weapons, Germany could return to France and defeat it.

Meanwhile, across the border in France, there was no interest in more war. The French found little pleasure in their victory, which they’d purchased at the cost of 1.3 million dead. The nation went back to work, but this proved difficult with so many men missing.

The French government in these years poorly served their citizens. Bitterly divided by political factions, France proved unable to develop an effective policy for national defense. However, it built a massive military structure in anticipation of the next war. It has become the symbol of narrow-minded planning.

It was the Maginot Line; a system of forts, bunkers, and observation posts along the border it shared with Germany. When completed, these hundreds of buildings were considered the most advanced fortifications ever built. France believed the line was impregnable; the country no longer needed to fear German invasion.

Unfortunately, the line left two entry points wide open. At its northern end, its defenses ended where the French border entered the Ardennes Forest. French authorities believed no defense was needed in this area because rivers, broken ground, dense woods, and winding roads made the Ardennes impassible to a modern, mechanized army.

Beyond the Ardenne lay the border with Belgium. The French didn’t extend the Maginot Line into this area because they had a mutual-defense treaty with the Belgians. If Germany invaded Belgium, the French army would cross the border to fight alongside their allies. But as war approached, Belgium declared its neutrality. Hastily, the French and British began extending the Maginot Line to the coast.

On May 10 as French and British troops rushed into Belgium to engage the Germans, another German army group, with a million men and 1,500 tanks, rolled through the impassable Ardennes Forest to strike at the rear of the Allies. The end came soon afterward.

Today some Americans firmly believe France was defeated because it simply did not defend itself. The French army, for the most part, simply surrendered when they saw the Germans. The accusation is conveniently revived whenever Franco-American relations turn hostile.

The problem with the French-didn’t-fight theory is that it doesn’t explain the 290,000 French soldiers who were killed or wounded in only six weeks of fighting.