The Guggenheim: An Assessment of Wright’s Masterwork

On a blue afternoon toward the end of October in 1959, a number of notables gathered at 1071 Fifth Avenue in the city of New York. They were met to dedicate the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Aside from a motor salesroom on Park Avenue, this mass of concrete was the city’s only example of work by the world’s most famous architect, Frank Lloyd Wright. Therefore its opening was an occasion for oratory, and thousands of citizens waited behind barricades while the men of distinction sounded off. The mercifully short speeches ended by 2 p.m., and the patient public shuffled in to view the wonders of the Guggenheim.

The visitors saw an enormous circular room, 75 feet high, topped by a dome of geometrically patterned glass. Around and above them a gently graded ramp rose for seven stories, its walls affording exhibition space for 120 pictures from the museum’s collection of contemporary art. Places to sit and rest the feet tormented by the ramp’s hard marble flooring were scarcer than teetotalers at a brew master’s ball. Few of the visitors complained of this discomfort, or of anxiety that might be caused by the lowness of the parapets around the looming void between the ledges, for all knew that something fundamental and astounding was here. Instead of strolling from room to room, as in every museum hitherto known to man, they were “enjoying an experience in the continuity of space.”

As they flowed downward and outward, the visitors exclaimed: “Thrilling!” “Grand!” “An indescribable joy!” Among professional critics, the enthusiasm was equally great. … The New York Herald Tribune summed it up by reporting that the Guggenheim had “turned out to be the most beautiful building in America.”

Shutterstock

There were those who disapproved. These objectors called Wright’s work a washing machine, a marshmallow, a cupcake, a corkscrew, an imitation beehive, and an inverted oatmeal dish.

A bystander paraphrased Kipling by murmuring, “It’s ugly — but is it art?” And the New York Mirror published an editorial titled “THE MONSTROSITY,” calling on the Guggenheims to “prove their love for New York by tearing the thing down.”

Amid the controversial publicity surrounding the dedication of the Guggenheim, one thing was clear — Frank Lloyd Wright had achieved fame beyond any American artist. In fact, he was one of the most renowned Americans in any line of work, recognized as promptly as a champion athlete or a television star. People got to their feet when he entered a room, as though before royalty. And, his stock answer to the question, “Which do you consider the greatest of your buildings?”

“The next one,” Wright would reply with a twinkle. “Always the next one.”

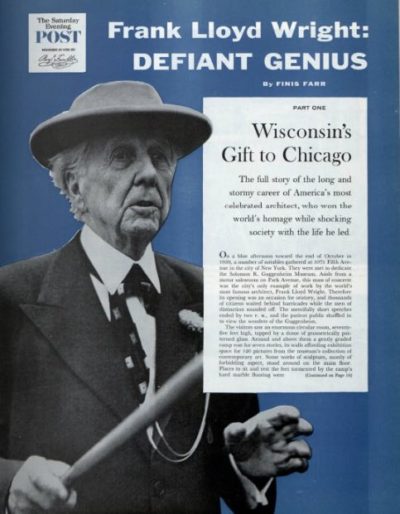

—“Frank Lloyd Wright: Defiant Genius” by Finis Farr, January 1961.

Read the full five-part series at saturdayeveningpost.com/wright.

This article is featured in the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Frank Lloyd Wright: Defiant Genius

In 1961, the Post published a five-part series on Frank Lloyd Wright. The series takes an in-depth look at Wright’s brilliant architecture, stormy home life, and many idiosyncrasies, both real and apocryphal.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Long and Stormy Career

Two springs after the Civil War ended — and exactly 150 years ago on June 8, 1867 — Frank Lloyd Wright, one of this country’s most original forces of nature, was born to an eccentric minister father and schoolteacher mother in pastoral Wisconsin. Few clues, other than, possibly, his affinity for playing with building blocks, could have foretold his future as an iconoclast who would help shape and even define modern society.

Frank Lloyd Wright is considered, in the eyes of many, the most consequential American architect of the 20th century. But while Wright’s influence can be seen all around us, notes Russell Davidson, past president of the American Institute of Architects, it’s easy to forget how influential he is. Consider this: buildings that emphasize open floor plans featuring large glass picture windows pulling in natural light and fronting views of the outdoors; fireplaces anchoring common areas where families gather; backyards treated as sanctuaries; horizontal roof pitches allowing more sky to pour in; even radiant heating. All these are design elements developed by Wright and his creative teams or inspired by his dictum that the features of a building must be in harmony with the rhythms of daily human life.

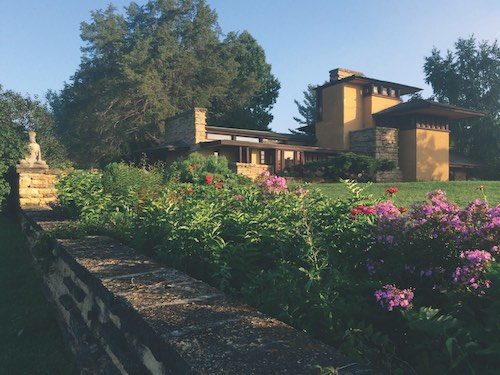

Nearly 92 years after his birth, on April 9, 1959, Wright was laid to rest in a modest grave not far from his compound in Spring Green, Wisconsin. Called Taliesin, a Welsh name meaning “shining brow,” it is a perfect example of Wright’s belief that buildings be seen as organic extensions of their natural settings.

There is no monumental tombstone to commemorate him. Only a modest protruding rock accompanied by an epitaph that reads, “Love of an idea is the love of God.” And, in fact, as we explain below, Wright’s body is no longer there.

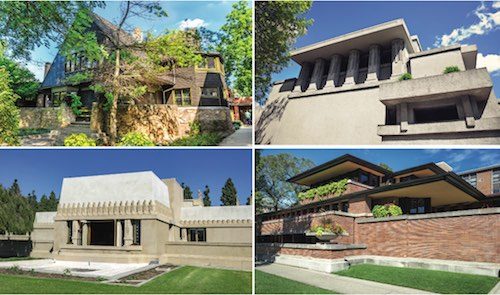

In all, Wright had direct involvement with plans for more than 1,000 structures of various kinds, including houses, offices, churches, hotels, schools, museums, college buildings, a national park pavilion, and a high-rise — many of those remaining now designated as national landmarks.

It’s only fitting that The Saturday Evening Post should mark Wright’s remembrance. The Post featured Wright’s work on several occasions over the seven decades of his career (for an excerpt, see “Wright’s Masterwork”). Make no mistake, Frank Lloyd Wright flaunted a gargantuan ego and often came across as a scold to lesser architectural lights. His trademark eccentricity — being sharp-witted, opinionated, always dapperly dressed with trademark hat and walking stick — evoked an air of dandyism. And yet those closest to him say there was a softer, playful, self-deprecating interior who yearned for validation.

Wright identified as a pastoral Midwesterner who craved contact with the outdoors. Famously, he once observed, “Study nature, love nature, stay close to nature. It will never fail you.”

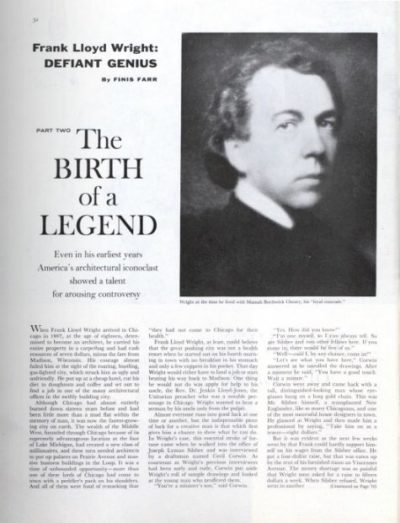

As a young draftsman-in-training in Wisconsin, he knew that he needed to prove himself in the big city. He arrived in bustling Chicago 16 years after the disastrous Great Fire of 1871. The need to rebuild produced a boom in demand for architects. The volume of work that accompanied reconstruction, and the growing professional class choosing to live in nearby suburbs, became an impetus for reflection about the function of homes and the essence of community.

Wright fell under the tutelage of architect Louis Sullivan, 11 years his senior and a fellow genius destined to be remembered as the “father of modernism.” Sullivan was already laying the foundation for a new emerging visual language, what we now know as the Prairie style. The home, to them, wasn’t merely a place of shelter and sleep but a vessel to stimulate the mind.

The Prairie style’s distinctive features are lower-slung, horizontally aligned structures honoring the open, often treeless expanse of the Midwestern prairie. An essay by Kimberly Elman Zarecor, associate professor of architecture at Iowa State University, elaborates on this philosophy: “Organic architecture involves a respect for the properties of the materials — you don’t twist steel into a flower — and a respect for the harmonious relationship between the form/design and the function of the building (for example, Wright rejected the idea of making a bank look like a Greek temple). Organic architecture is also an attempt to integrate the spaces into a coherent whole: a marriage between the site and the structure and a union between the context and the structure.”

To put it another way, “Wright had a highly developed way of making the building feel like it was part of its site, rather than placed on top of its site,” Davidson explains.

Central to Wright’s sensibility was echoing patterns and forms found in nature. Such fidelity did not always extend to human relationships. Thrice married, he was the father of eight children by different partners. “Despite the womanizing angle that some stories have taken, Wright was an early feminist,” notes Timothy Totten, who’s studied Wright for more than 25 years and whose “Night with Wright” presentations help to spread his enthusiasm for the great architect. “He believed in equality for women in his studio — more than 100 women served in his practice as apprentices and architects during his career — and the great love of his life, Mamah Borthwick.”

Courtesy Taliesen Preservation.

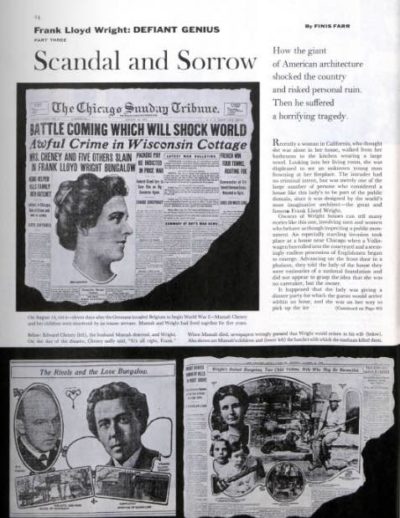

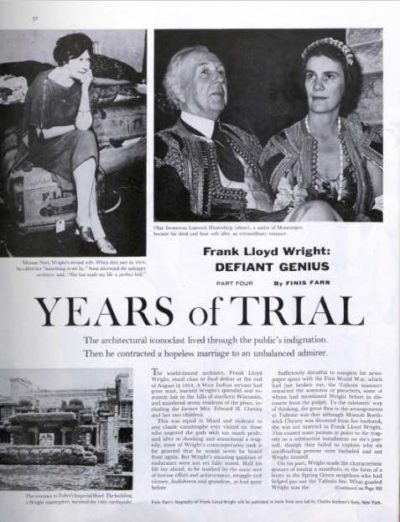

Borthwick was the wife of Wright’s neighbor, and the two had a well-publicized affair. Abandoning their spouses, they ran off to Europe together, later resettling at Taliesin in Wisconsin, which Wright built for her. But Taliesin, a place of profound bliss and exaltation for Wright, would become a source of unspeakable pain. On August 15, 1914, while Wright was in Chicago on business, Borthwick and six others — including her two children — were murdered by a deranged, disgruntled servant who killed them with an ax and set fire to the building. Borthwick’s death sent Wright tumbling into a depression. Many thought his best days were behind him, and for the next decade, demand for his services went into decline. But “Wright had an uncanny ability to reinvent himself through his work and find new inspiration,” Davidson says.

In rebounding to create some of his greatest works, Wright also benefited from a prodigious amount of luck, adds Totten, “a trait he shares with quite a few of the grand movers of the last century, from Einstein to Steve Jobs, in that he was born at the right time and refused to be deterred by setbacks. The revolution in modern architecture of the late 19th century, coupled with serendipitous engineering advancements of the early 20th century, meant he could push architecture the way he did.”

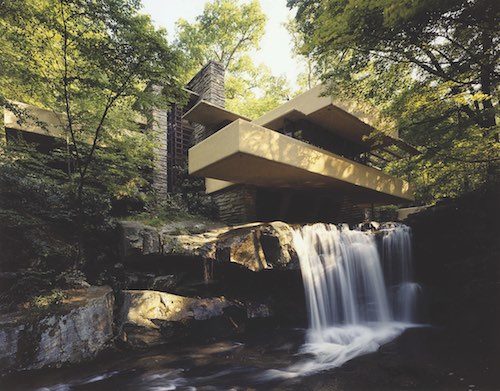

In many respects, the resurrections that occurred at Taliesin can be viewed in hindsight as a metaphor of Wright’s own path, which played out in two more acts. This is most evident, Davidson notes, in the progression of thinking that can be seen from his early works to his most famous midlife masterpiece, Fallingwater, and his grand finale completed in his last year of life, the incomparable Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. Designed in 1935, Fallingwater, a residence created for the Kaufmann family in southwestern Pennsylvania, famously incorporated the path of a stream and natural waterfall into its building envelope. Audacious in Wright’s own time and even today, the site plan allows the cascade to course through the living spaces.

Owning a Wright home was — and still is — a prestigious thing; being able to claim him as a friend caused clients to swoon. “He was devilishly charming and had a generally bright, sunshiny disposition most times; how else to explain all the clients who willingly gave significant resources for him to build projects that pushed them beyond their own comfort zone?” Totten asks.

“Wright had ideals about the way he thought people should live and work,” Totten continues. “It makes sense that so many clients spoke about their homes and, in some cases, their offices as if they were other members of the family. Because he listened to clients and anticipated their needs, his built projects just seem to ‘fit them perfectly’ and made them feel a greater sense of intimate connection.”

Still, working with Wright was not easy. He was a stickler for detail, and despised having to compromise. As he once wisecracked, “The physician can bury his mistakes, but the architect can only advise his client to plant vines.”

There’s the story of an exchange between Wright and a client, Harold Price Sr., who was building a second project with the great man. Price showed up at an Easter party wearing a new bright-blue sport coat. Seeing it, Wright reportedly said, “Harold, how have I left you enough money to buy a new suit?”

Indeed, no one ever accused Wright of sensitivity to the feelings of others. He famously dismissed Ernest Hemingway, who had questioned a Wrightian conception for the Grand Canal in Venice, as nothing more than “a voice from the jungle.” He remarked that Daniel H. Burnham, chief designer of the Chicago lakefront, “would have been equally great in the hat, cap, or shoe business.” He described the prestigious French-Swiss architect Le Corbusier as “only a painter — and not a very good one.”

Explaining himself in a TV interview, Wright claimed that he preferred “honest arrogance” to “hypocritical humility.”

Courtesy The Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

Arrogance doesn’t build allies. And, as a proponent of the “sole genius” approach to his profession, notes Davidson, he gave little or no credit to his many collaborators. “This self-permission to be arrogant has unfortunately tainted the view of many architects and is still the reason that the public believes that many architects are not relevant to their ordinary lives,” Davidson says.

For all his egotism, Wright had a soft spot for working people. He believed everyone deserved to have tasteful, functional living spaces affordable to their means. Davidson recalls, as a teenager, helping a friend deliver newspapers in a neighborhood designed by Wright near Pleasantville in the Hudson River Valley. The community, known as “Usonia Homes,” was his rebuttal to the cookie-cutter developments then sprouting up in postwar America for its emerging middle class. The homes in the development were modest but functional and featured aspects of his organic design — flat roofs, kitchens that doubled as work spaces, dining rooms with built-in seats and tables, and living rooms with fireplaces where families could gather in cozy comfort.

The Guggenheim Museum is thought by many to be Wright’s capstone, yet it caused controversy and epic resistance from traditionalists. Wright wanted to push museum design to a new level and push museum administrators out of their comfort zones. He aggressively fired back at critics who claimed that the Guggenheim plan was a monument to himself. “On the contrary,” he said, “it was to make the building and the painting an uninterrupted, beautiful symphony such as never existed in the World of Art before.”

The Guggenheim remains a New York landmark to this day, hugely popular with tourists and native New Yorkers alike. The National Park Service says that among all of the Wright properties in its inventory, the Guggenheim “represents the culmination of a lifetime of evolution of Wright’s ideas about ‘organic architecture.’”

Wright died just a few months before the Guggenheim’s opening in autumn 1959 to huge fanfare – and plenty of controversy. Seems the perennial iconoclast found a way to continue being the center of attention, even in death.

More attention would follow more than 25 years later when, near the end of her life, Wright’s third wife, Olgivanna, surprised the world by announcing it was her husband’s intention to be cremated. Despite a furor of protest, and against the wishes of his children from his first marriage, his body was exhumed from its resting place at Taliesin and duly cremated. The ashes were moved to Arizona and placed in a shrine with hers.

It doesn’t matter, of course, where Wright is buried; it’s his surviving buildings, all around us, that stand the test of time. In their shadows and light, it is said, you can still feel his soul and spirit.

Todd Wilkinson has been writing about art, nature, and the West for nearly 30 years. For more, visit toddwilkinsonwriter.com.

This article is featured in the May/June 2017 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.