Saturday Evening Post History Minute: The Greatest Political Comeback in American History

Featured image: Warren Harding and Calvin Coolidge (Library of Congress)

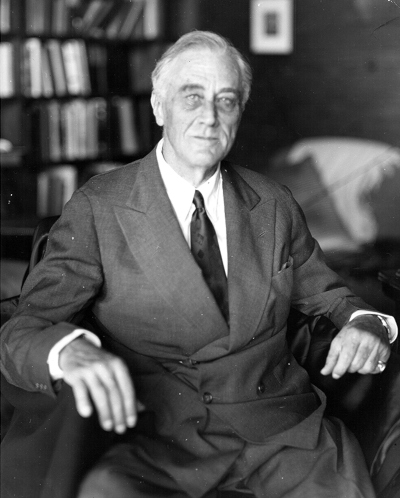

Remembering the Day FDR Died

The candlestick telephone was a relic even then. The black upright device with a round mouthpiece and a hook to one side with its bell-shaped receiver sat on the desk of the telegraph editor, George Dodge, in the city room of the Chicago Daily News that Thursday afternoon, April 1945.

It was quiet. Almost 5 o’clock and my quitting time. But I was still sitting at the city desk, a copygirl for four months, long enough to move over into that spot when the city desk secretary left for the day and take phone calls from beat men around the city checking out.

I saw George Dodge reach for the telephone, a direct line from the Associated Press (AP), positioned at the far edge of his desk, used to alert editors to big news they might not catch in the regular stream of printed copy coming in on the Teletype machines in the tube room. He listened, pushed the phone back and away, and said, softly, “Roosevelt is dead.”

A momentary, complete, end-of-the-world silence was broken by the sound of his swivel chair hitting the glass panels in the bookcase behind him as it shot back when he jumped up and raced to the tube room.

The assistant city editor to my left said, “Clear the decks for action.”

City Editor Clem Lane, who had gone down the hall with the last deadline long passed, came back into the city room as if shot out of a cannon, followed by the Director of the Daily News Foreign Service, Hal O’Flaherty. To this day I wonder how they heard, but they had. And Managing Editor Everett Norlander, whose office had a glass wall overlooking the city room, came through the door. They gathered around George Dodge at the copy desk.

It was a horseshoe shaped desk with the chief copy editor in the slot and some eight or ten copy editors facing him. While editors read over the articles under their umbrella, all stories went to the copy desk to be marked up for the linotype operators who would set them in type: paragraphs, inserts, consistency of style — avenue was always av. in the Daily News — and write the headlines. They were then sent down to the composing room in a round container the copy editor placed in the pneumatic tube.

Clem Lane called to me to get the clips on Truman.

Ah yes. The vice president, for not quite three months.

I ran down the hall to the library — the morgue of the old days (clips of dead stories) — and they’d heard. They had overflowing white envelopes of clips of President Franklin D. Roosevelt spread out and, I can still see it, one small envelope of clips on Vice President Harry S. Truman. I grabbed it and ran back to the city room, where Clem Lane was standing near reporter Bob Lewin at Lewin’s desk, fortuitously just across the aisle from the copy desk.

Bob, who usually covered Labor, was to do the story on the new president.

Because this was an EXTRA or Special Edition, it was squeezed into the limited remaining time to publish, prompting Bob to do what are called “short takes.”

Rather than writing the story and going on to the next page, Bob wrote two or three paragraphs, then pulled the copy out of the roller of his typewriter. Reporters used “books” of five pages of copy paper with four pages of carbon paper (for copies before Xerox copying). He pulled out the carbons and handed the top sheet to Lane, who turned to read it at the copy desk. Then Lewin rolled in a fresh book.

To further shorten the time, I pulled out the copy after the next three paragraphs, drew out the carbons, ripped off the top sheet and handed it to Clem Lane, placing a copy at Bob’s left for reference, careful not to disturb the newspaper clips he had fanned out there.

Looking back, it was a bit like those scenes in movies where folks hand the pails of water off to the next person to fight a fire. We handled the story in short takes that got to the next editorial station in record time, and then on down to the composing room.

“Okay. That’s it,” Mr. Lane said, wrapping it up as we ran out of time.

Lewin slumped back in his chair in relief. And I headed back to the city desk, where Charlie Cleveland, a rewriteman and future political star, was writing a piece on the reaction he’d been able to get from the stream of suburban commuters in the Daily News Building concourse headed for the adjoining Northwestern train station. I took his story to Mr. Lane and then on to the copy desk, and it made it into the special edition.

When it was too late for any more stories to be published that day, the city room settled into a routine that was almost normal, but with the undertow of this stunning event, the breaking wave of the news that the 32nd president of the United States was dead.

To understand how big that was, you have to understand how big Roosevelt was. He took the oath of office March 20, 1933, as the full impact of the Great Depression was registering on the nation, his inaugural address containing the oft-quoted phrase: “We have nothing to fear but fear itself.”

But there was a lot of fear.

Certainly, enough to go around.

I once heard the former president of the University of North Carolina system recall his youth in one of the mill towns in North Carolina near Charlotte. I forget whether it had four mills and three banks or four banks and three mills. It didn’t matter. They woke up one morning, he said, to find the banks were closed and the mills had shut down. No jobs. And no money. With the banks closed, you couldn’t even withdraw your own money.

Newspaper photos and documentaries show the long line of unemployed men stretching down the length of buildings to get a hot meal at soup kitchens.

I remember men occasionally coming to our kitchen door to ask humbly, hopefully, if any work needed to be done, something they could do. I was a child, and the devastation of the Great Depression didn’t fully sink in, as I had enough to eat and went to school every day as usual, but I did see unemployed men on street corners in Detroit when we went there occasionally. They often had red apples or tin cups with pencils for sale.

Then came Pearl Harbor.

When I think of Roosevelt in a historical sense I think of the Great Colossus of Rhodes, the towering bronze figure at the harbor of Rhodes — one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Some images of the giant figure show him with one foot on one side of the harbor, the second on the other. Roosevelt, in my analogy, had one foot in the Great Depression, the other in World War II.

And to shape the post-war world, he met with Churchill and Stalin at Yalta. He showed his age then and did not look well.

But no one foresaw him dying of a cerebral hemorrhage that Thursday, April 12, 1945, while in Warm Springs, Georgia, where he went often because he was a victim of polio and the springs helped him.

Before I left about 8:00 p.m., Mr. Lane asked me to take copies of the statements that had come from local and state leaders down the hall to the office of Lloyd Lewis, the chief editorial writer. When I reached the doorway, he was sitting in the dark, looking out at the city, the sparks from the electric streetcar below little red stars in the night.

He sensed my presence and turned, musing aloud: “I wonder what the world will be like without him.”

“I don’t know, sir.”

He looked at me again, 19, in my pleated plaid skirt and loafers, fresh off the Northwestern University campus, and nodded. “Of course.” He told me to put the statements on his desk.

The other thing I remember from that night is the editors gathered around the news desks, absorbing the news — which they were good at: that was their business — when someone wondered what kind of president Harry Truman would be. Hal O’Flaherty said, “If there’s anything to the American system, the man will rise to the office.

I think of that occasionally when I read reviews of books by presidential historians or hear a group of historians on TV talking about presidents and their place in history, unanimously putting Truman in the top tier.

But he was an unknown that night, a small white envelope of clippings next to the array of envelopes, large and small, on Roosevelt.

What President Roosevelt meant to Americans was captured in an account by David Brinkley, then a young reporter in the nation’s capital, of the funeral train bringing the president’s body back to Washington from Warm Springs:

Up through the South the train rolled at twenty-five miles an hour. The family asked that it be moved slowly because all along the way, throughout the afternoon and throughout the night, people lined the tracks to see it pass. In darkness, the Connaught [the private car carrying the body] was softly lit, the shades raised, and people outside could see the American flag atop the coffin, the honor guard in dress uniforms and, occasionally, Mrs. Roosevelt sitting there. The people stood along the tracks beside tobacco and corn and peanut fields, in the cities and towns. Even at 3 a.m. they were out there. They held their children up to see. They cried. They knelt. They sang hymns. No one could count the people lining the track through town and country from Warm Springs to Washington. Some guessed two million.

Silent homage from the people whose lives he had touched. The realization, in the words I heard George Dodge say as he pushed the black candlestick telephone away that Thursday afternoon: “Roosevelt is dead.”

***

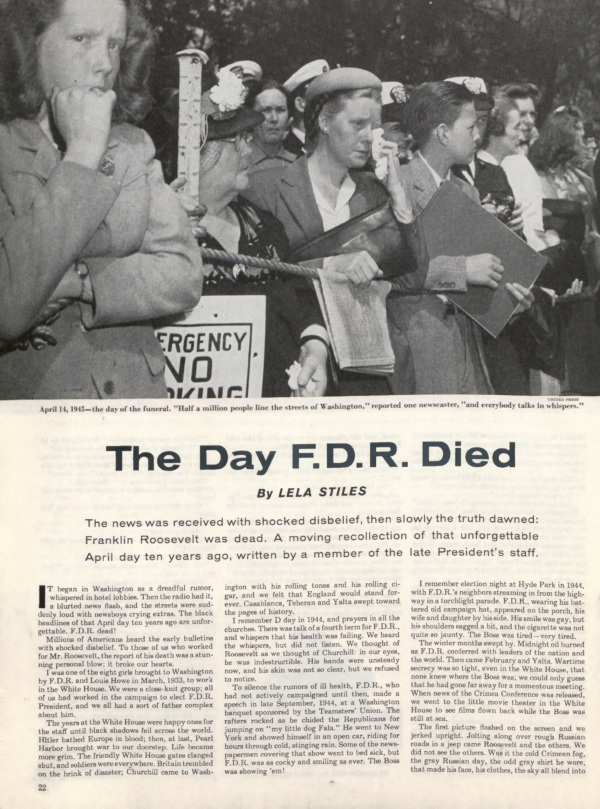

For another perspective on this day, read “The Day F.D.R. Died,” from the April 16, 1955, issue of the Post. The story is a remembrance by one of President Roosevelt’s secretaries, 10 years after his death.

Featured image: Franklin D. Roosevelt’s casket is removed to the Caisson at Union Station for his funeral procession. Washington, D.C. (Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library & Museum)

Considering History: The New Deal, White Supremacy, and How the South Won the Civil War

This series by American studies professor Ben Railton explores the connections between America’s past and present.

On April 9th, 1865, just under four years after the Civil War’s opening salvo at Fort Sumter, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Virginia’s Appomattox Court House, formally ending that divisive and destructive national conflict (although some Confederates refused to surrender for months thereafter). The attempt by 11 Southern states and a few Western territories to create a distinct nation organized around founding principles of slavery and white supremacy, the Confederate States of America (CSA), had failed, and the United States was reconstituted as a unified nation once more.

Yet over the next half-century, as I’ve written about for this column and elsewhere, a neo-Confederate perspective on American history and identity came to dominate the national landscape. A vital new book, historian Heather Cox Richardson’s How the South Won the Civil War: Oligarchy, Democracy, and the Continuing Fight for the Soul of America, links that trend to the development of and battles over the post-Civil War American West. But by the early 20th century a neo-Confederate, white supremacist narrative likewise dominated national politics and policy, as another of this week’s historical anniversaries can help us remember.

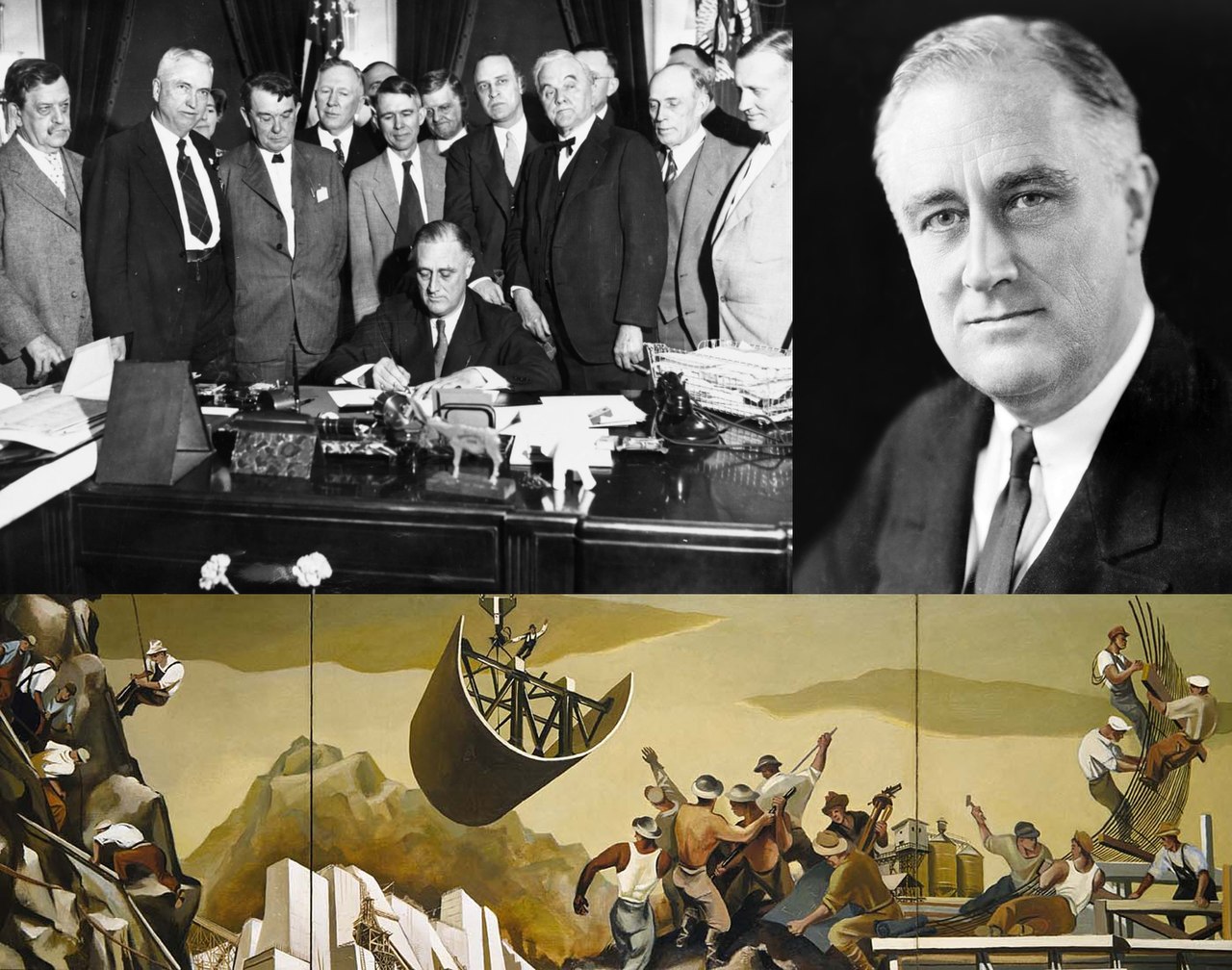

On April 8th, 1935, President Franklin D. Roosevelt introduced the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act, a request to Congress for $4.88 billion to create and support a number of public works programs within the overarching frame of the era’s evolving New Deal responses to the Great Depression. Although the Act’s targeted unemployment relief was controversial and much of it was eventually never allocated, the Act did lead directly to the creation of many of the New Deal’s most famous and successful public works programs, including the Works Progress Administration (WPA) and its subsidiaries such as the Federal Art Project and the Federal Theatre Project, the National Youth Administration, and the Rural Electrification Administration.

Yet the New Deal’s programs, like the Roosevelt Administration overall, consistently gave in to the demands of Southern white supremacists and discriminated against African Americans (and other Americans of color) in a number of distinct yet interconnected ways. Many of those Southern white supremacists were Democratic Congressmen whose votes Roosevelt was courting to secure passage of the New Deal, a political reality for the Democratic Party in this early 20th century period (before the party realignment of the 1950s and ’60s). Yet the very fact that Roosevelt needed those Southern Congressmen’s votes reflects the political and social power of this white supremacist community in 1930s America. And the various forms taken by these New Deal racial discriminations illustrate the destructive effects of white supremacy on millions of Americans.

The most overt such discriminations were the ways in which numerous New Deal programs were crafted to either exclude entirely or limit the opportunities of African Americans. The Federal Housing Authority (FHA) excluded the African-American community overtly, refusing to guarantee mortgages for many African Americans seeking to buy homes; the Social Security Act (SSA) did so more indirectly but just as potently, excluding agricultural and domestic workers (two categories in which the majority of African Americans and many other Americans of color worked) from its protections. Other programs discriminated by creating segregated and unequal structures that mirrored Jim Crow systems: the National Recovery Administration (NRA) offered white Americans the first opportunity at its jobs, and paid African American workers substantially less; the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) maintained segregated and significantly less well-maintained camps for African Americans.

The exclusion of agricultural workers from the SSA was paralleled and extended by another, perhaps unintended but still hugely destructive form of discrimination, one exemplified by the Agricultural Adjustment Administration (AAA). As created by the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act, the AAA offered farmers subsidies in exchange for limiting their production, a policy intended to limit overproduction and help raise prices. But since many African-American farmers worked as sharecroppers, a system that developed alongside the re-emergence of Southern white supremacy in the late 19th century (part of what historian Douglas Blackmon has called “slavery by another name”), it was their white landlords who received the subsidies, and the farmers who were unable to produce and earn from their crops. The AAA thus pushed more than 100,000 African-American farmers off their land in 1933 and 1934 alone.

Beyond the New Deal’s programs and policies, the Roosevelt Administration likewise appeased white supremacists through its inaction on and even opposition to anti-discrimination laws in the period. The most prominent and ironic example was President Roosevelt’s opposition to an anti-lynching bill on which his wife Eleanor Roosevelt had collaborated with NAACP President Walter White and Congressional allies. Roosevelt told the pair in a private meeting that he could not publicly support the bill, arguing about the Southern white supremacists: “If I come out for the anti-lynching bill now, they will block every bill I ask Congress to pass the keep America from collapsing. I just can’t take the risk.” When the bill, known as the Costigan-Wagner Act, nonetheless came before Congress in February 1935, those Southern politicians threatened a lengthy filibuster, and the president remained silent; the bill died without a vote, and no federal anti-lynching legislation would ever be passed (until earlier this year, in a largely symbolic gesture).

The combined effect of all these discriminations and exclusions was that African Americans not only continued to occupy a significantly segregated and disadvantaged position in American society, but also did not receive the same benefits and opportunities from these vital programs as their peers — not during the depths of the Depression, and not over the decades since when many of those programs have continued to aid American communities. In his groundbreaking 2014 essay “The Case for Reparations,” journalist and public scholar Ta-Nehisi Coates argues that these discriminations (he particularly focuses on housing inequities such as those perpetrated by the Federal Housing Authority) have cost African-American individuals, families, and communities tens of millions of dollars across the 20th century and into the 21st, yet another profound and painful effect to the white supremacist perspective’s powerful hold on American politics and society.

Featured image: An artist’s rendering of the surrender of Confederate General Robert E. Lee to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. (Library of Congress)

On the Side of Social Security

Eighty-two years ago, Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Act, a part of the Second New Deal that provided the foundation of government assistance in the country.

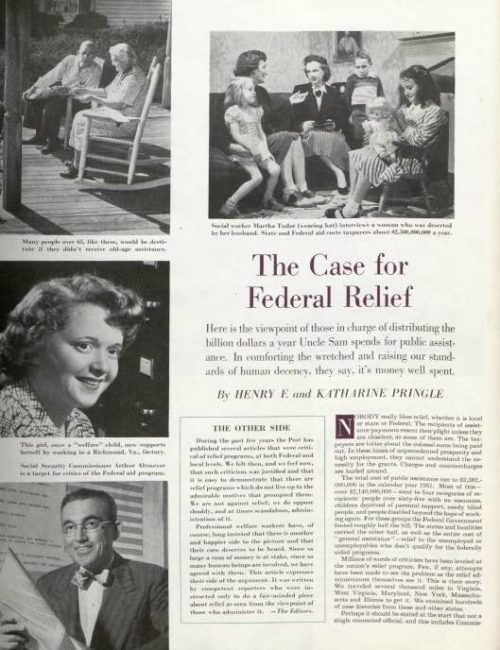

Although the Post was often critical of federal and local relief programs following Roosevelt’s New Deal, Henry F. and Katharine Pringle’s “The Case for Federal Relief” in 1952 looked at the beneficiaries of welfare and argued the necessity of programs that give security to the unemployed, elderly, abandoned, and disabled. The authors asserted, “Public assistance does not make bums out of people, if it is accompanied by good social work. The right kind of aid, in money, for minimum security plus guidance to get the recipient back on his feet, if that is possible, is the answer.”

In 1952, the public wondered whether “hillbilly” children ought to receive funds for shoes — since they weren’t accustomed to wearing them — or whether releasing the names of people receiving public assistance might deter greedy deceivers out of embarrassment. Although most people tend to agree on a sort of social safety net, the implementation of such is rarely unanimous.

The President with the Most Successful “First 100 Days”

The concept of the “first hundred days” reduces a large, complex undertaking — the achievements of a president — to a deceptively simple scale.

Franklin D. Roosevelt first used the term on July 24, 1933, to describe the early accomplishments of his administration. In a radio address to the nation, he said it was time to look back at “the crowding events of the hundred days which had been devoted to the starting of the wheels of the New Deal.”

FDR’s accomplishments were impressive. He called the 73rd Congress into session early, and before his first week was over, presented his Emergency Banking Act.

At the time, banks across America were failing at a fearful rate. Fourteen hundred banks had shut their doors in 1932. Before 1933 ended, another 4,000 banks would close. The Emergency Banking Act closed every bank in America for one week, enough time for the public panic to subside. When the banks reopened, Americans began re-depositing their savings.

The Act was only the beginning of Roosevelt’s initiatives over the first 100 days. Before Congress adjourned, the administration also

- took U.S. currency off the gold standard, effectively allowing the government to print and distribute money to the struggling banks

- imposed regulations on U.S. banks that separated commercial banking from investment banking, and prohibited banks from using their assets in stock market speculations

- established an insurance program for bank accounts (the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation)

- introduced new regulation of the stock market (creating the forerunner of the Securities and Exchange Commission)

- created an agency that paid farmers not to raise crops, in order to raise the prices they got for their produce

- launched the Civilian Conservation Corps, which eventually put 250,000 young men to work on conservation projects

- started a program (the Tennessee Valley Authority) to provide electricity to impoverished rural Americans and raise their standard of living

- created a controversial program that placed pricing controls on businesses in an effort to raise the cost of goods

- began the Public Works Administration to create jobs building schools, hospitals, airports, dams, and other public projects

- provided training and direct relief to the unemployed

If it seems impossible for a president to accomplish all this in 100 days, it is. Roosevelt couldn’t have done this on his own, and he knew it. He relied on three other factors.

The first was Congress. Most of the changes came through legislation, not executive orders. Roosevelt knew he could rely on the support of other Democrats who made up the majority in both houses. (The 73rd Congress had 311 Democrat, 117 Republican, and 5 Farmer-Labor representatives in the House; and 59 Democratic and 36 Republican senators, plus one from the Farm-Labor Party.)

Second, there was a national sense of urgency. One in five Americans was out of work. Employed Americans feared their job or savings might disappear overnight. Congressmen knew they had to act, even to try unconventional means. Southern Democrats sometimes objected to Roosevelt’s program, but progressive Republicans from western states stepped in to throw their support behind the president.

Third, Roosevelt had strong support from the American public, which had just elected him by 472 electoral votes to President Hoover’s 59. (Hoover lost the popular vote in 1932 by the same sizeable percentage he’d won it in 1928: 17%.) They had voted for, and would support, any new measures.

Other presidents haven’t had those advantages. When President Johnson entered the White House, he enjoyed a honeymoon phase with the press and the public. It enabled him to push the Civil Rights Bill, which had been hung up in Congress. He introduced a wide range of bills, hoping to beat Roosevelt’s record, but he failed.

President Reagan’s first 100 days got off to a promising start when 52 Americans being held hostage in Iran were released on the same day he took office. He also proposed $41 billion in budget cuts and major tax breaks during his first three months. President Obama took action on an ambitious number of foreign and domestic issues, including a $700 billion stimulus bill, but he still fell short of FDR’s record of change.

Roosevelt still holds the record for accomplishment in his first 100 days in terms of major legislation passed, but considering that it took a financial disaster and a desperate sense of national urgency to achieve so much, perhaps it’s just as well we never see his record beaten.

Featured image: Shutterstock

Ben Franklin Used Fake News

It may seem like our political climate, in which politicians and journalists are accused of inventing phony stories, is unprecedented. Yet there are similarities to past events, and some of the perpetrators of early political chicanery may surprise you.

For example, in 1782, while still representing the United States in Paris, Benjamin Franklin printed a fake edition of an actual Boston newspaper, The Independent Chronicle. Amid the fictitious ads and articles, Franklin inserted a made-up story about the massive slaughter of white settlers on the frontiers of New York. Native Americans, in the service of the British forces, had collected 700 scalps from men, women, children, and even infants, Franklin lied.

When the news reached America, it was reprinted in papers throughout New England. The story helped stiffen American resistance to the British, who were now seen as using Indians to terrorize settlers. Released in Paris, the story also helped sway European opinion against England.

Franklin’s “fake news” was just the start of a long tradition in American politics.

As we noted in “Crude Language on the Campaign Trail,” presidential campaigns have often been marked by fabricated stories and synthetic scandals. Even after the race, the slander often continued.

In 1939, Stephen T. Early, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secretary, shared several examples of disinformation campaigns directed against the president.

Roosevelt enjoyed broad support among voters, particularly in the early years of his presidency. But he remained a controversial leader for many Americans. Some of his opponents hoped to blacken his reputation with reports of corruption or dishonesty in the White House.

In a file he marked “Below the Belt,” Early gave examples of these fake news stories. Some hinted at sinister, international conspiracies implicating Roosevelt, a foreign-born Supreme Court justice, and labor leaders, among others. One story claimed President Roosevelt had prevented the capture and trial of the true kidnappers of the Lindbergh baby. The kidnappers, it argued, were protected by the president and were still kidnapping and murdering.

Early wondered, as many Americans do today, “just how gullible do these muckrakers think the American people are?”

Roosevelt, however, refused to be baited by these stories. When a publisher reported that the president had fallen into a coma, he offered to print a retraction if the White House issued a denial. All he got was silence. Roosevelt refused to reward him with more media attention.

Unfortunately, in our era of 24-hour information, ignoring even flagrant fake news doesn’t seem to be an option. What and whom are we to believe? In both the literal and figurative sense, we are left to our own devices.

Forester in Chief

Editor’s note: We remember President Franklin Delano Roosevelt as a leader who took the reins of office in the depths of the Great Depression and, in a record-setting span of nearly four terms in office, steered a course back to prosperity. But few of us are aware just how much we owe FDR for his crusading efforts to save and improve America’s forests. “Think 3 billion trees planted, crucial landscapes saved, from the Okefenokee Swamp to the Olympic Mountains — and more acreage conserved than the size of California,” writes historian Nigel Hamilton.

Growing up in Hyde Park, New York, on a 600-acre family farm, FDR had learned at an early age how to manage land. When his father died while the future president was at Harvard, he took over the farm. “It was the beginning of FDR’s lifelong obsession with trees and the importance of trees to the environment,” Hamilton writes.

Just days after his inauguration, Roosevelt ordered that thousands of trees be planted in Hyde Park, New York.

That FDR, with the crushing weight of the Great Depression on his shoulders, found time for planting trees was tangible proof of his long-held conservationist convictions. “Forests, like people, must be constantly productive,” Roosevelt told the Forestry News Digest. “The problems of the future of both are interlocked. American forestry efforts must be consolidated, and advanced.” To that end he wanted to use forests to ease the economic crisis at hand.

On March 14, 1933, Roosevelt issued a memorandum for the secretaries of war, the interior, labor, and agriculture. “I am asking you to constitute yourselves an informal committee of the Cabinet to coordinate the plans for the proposed Civilian Conservation Corps [CCC]. These plans include the necessity of checking up on all kinds of suggestions that are coming in relating to public works of various kinds. I suggest that the Secretary of the Interior act as a kind of clearing house to digest the suggestions and to discuss them with the other three members of this informal committee.”

FDR convened the first meeting of the quartet of Cabinet members that March. The team was composed of George Dern, from War; Henry A. Wallace, from Agriculture; Harold Ickes, from Interior; and Frances Perkins, from Labor. During the meeting, Roosevelt nonchalantly sketched, on a scrap of paper, a flowchart of the CCC chain of command. As Perkins later explained, Roosevelt “put the dynamite” under his Cabinet members and let them “fumble for their own methods.” Roosevelt envisioned three types of camps: forestry (concentrated in national forest sites); soil (dedicated to combating erosion and implementing other soil conservation measures); and recreational (focused on developing parks and other scenic areas). From the get-go, Ickes was the New Deal’s taskmaster, with the impatience of a drill sergeant. In a symbolic gesture, Ickes ordered the doors to the Interior headquarters locked every morning at 9:01. Showing up late for work, by even a few minutes, meant instant dismissal. Throughout Roosevelt’s first term, Ickes promoted state and national parks with pluck and vigor, rebuffing right-wing senators who claimed the CCC was a Bolshevist threat to democracy.

Frances Perkins — the first female Cabinet officer in U.S. history and one of only two Cabinet secretaries to work for the entirety of Roosevelt’s tenure in the White House (the other being Ickes) — was tasked with coordinating the recruitment and selection of able-bodied CCC enrollees. Initially a quarter of a million unemployed, unmarried “boys” or juniors between ages 18 and 23 (later expanded to 28) were sought. The pool was later widened to include 25,000 veterans of World War I who had fallen on hard times; 25,000 “Local Experienced Men” (LEM) who worked as project leaders in the junior camps; 10,000 Native Americans, who would be assigned to improve reservations; and 5,000 residents of the territories of Alaska, Hawaii, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Perkins worried that Roosevelt was biting off more than he could chew. However, as the trees got planted, she soon became a believer.

What made the CCC more than just a dazzling work-relief program was the professional expertise the LEM brought to land reclamation. Skilled young physicians, architects, biologists, teachers, climatologists, and naturalists learned about conservation in a tangible, hands-on way. If not for the Great Depression, these workers would have found themselves engaged in upwardly mobile jobs. But by a twist of fate, as many of their diaries and letters home make clear, these LEM were indoctrinated in New Deal land stewardship principles. Later in life, after World War II, many became environmental warriors, challenging developers who polluted aquifers and unregulated factories that befouled the air.

Courtesy FDR Library

Having developed a working model for the CCC, Roosevelt delivered his plea to launch it with the passage of the Emergency Conservation Work Act, which would provide the authority to create, by statute, a “tree army” to provide employment (plus vocational training) and conserve and develop “the natural resources of the United States.” He sent his bill to Congress on March 21. Roosevelt made it very clear that reforestation projects wouldn’t interfere with “normal employment.” In a message to Congress, Roosevelt stated in part:

I propose to create a Civilian Conservation Corps to be used in simple work, not interfering with normal employment, and confining itself to forestry, the prevention of soil erosion, flood control, and similar projects. …

More important, however, than the material gains will be the moral and spiritual value of such work. The overwhelming majority of unemployed Americans, who are now walking the streets and receiving private or public relief, would infinitely prefer to work. We can take a vast army of these unemployed out into healthful surroundings. We can eliminate to some extent at least the threat that enforced idleness brings to spiritual and moral stability.

Roosevelt did a marvelous job of selling the CCC, answering congressmen’s questions forcefully but politely. At six press conferences, he invoked public works and the CCC. After a round of debate, the 73rd Congress passed S. 598, Public Law No. 5 on March 31, creating the CCC as a temporary emergency work-relief program. Roosevelt’s unstated hope was that what the New Republic called his “tree army” would eventually become a permanent agency.

Roosevelt hired American Federation of Labor leader Robert Fechner as the first director of the CCC. Originally from Chattanooga, Tennessee, Fechner, born in poverty, left school at age 16 and moved to Georgia to become a “candy butcher” on trains. Mild-mannered and collaborative by nature, Fechner was an intrepid labor reformer. Because of his sterling reputation for fairness — as well as his union background — he proved an inspired choice.

By mid-April, the program was coming to life. According to Roosevelt’s estimation, an 11-man CCC crew could, weather permitting, plant 5,000 to 6,000 trees per day. Surrounded by maps of America, the president studied rivers and streams, deserts and forestlands. “I want,” Roosevelt declared, “to personally check the location and scope of the camps.”

Roosevelt’s “tree army” became a legend from the start, and he became a forester-in-chief hero to many conservation groups. As historian David M. Kennedy noted, the public quickly understood that Roosevelt had a “lover’s passion” for trees.

All over America, CCC tent cities popped up like Boy Scout camps; they were soon replaced with rustic barracks. Each company unit of 200 CCC “boys” was a temporary village in itself. All sorts of bylaws, pledges, and rules of engagement were announced. The “CCCers” received three full meals each day and were issued olive-drab uniforms, which included pants, a shirt, gloves, two pairs of underwear, a canteen, and a pair of heavy, steel-toed boots. In time, Roosevelt and Fechner changed the uniform to a spruce-green color for the coat, pants, overseas cap, and mackinaw (the shirt remained olive). “The issuance of a new uniform distinctive from other governmental services will improve the appearance of the corps,” Fechner noted. “It will also aid in building up and maintaining high morale in the camps.”

Unlike the army, there were no guard houses, drills, saluting, or court-martials. But morale was important from 6 a.m. reveille to taps at 10 p.m. At just $30 per month, these young men weren’t going to get rich: $22 to $25 of their pay was mandated to be sent home to their families; what remained was spent at the canteen, on haircuts and snacks, or at the local nickelodeon. Topnotchers were able to boost their salary by becoming technicians. A gag circulated among new enrollees — “Another day, another dollar; a million days, I’ll be a millionaire.”

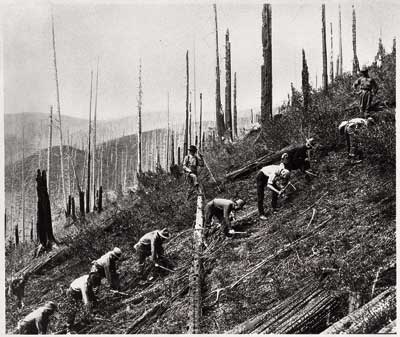

Uniformed enrollees started working at a breakneck pace to plant millions of trees, restore grass, build check dams, practice rodent control and kill invasive or destructive animals, prevent wildfires, and teach bankrupt farmers how to form soil conservation districts. Particularly concerned about California’s forests — which drought and arid conditions had made hyper-vulnerable to fire — Roosevelt instructed CCC crews to cut a 600-mile Ponderosa Way firebreak along the base of the Sierra Nevada in California, the longest such protective barrier in the nation. The CCC “boys” were also dispatched to do immediate battle in the drought-ravaged Great Plains and the soil-stricken American South. Even Puerto Rico had CCC camps, employing 2,400 men.

Roosevelt never meant the CCC to be a panacea for the systemic woes of the Great Depression, but it did save a vast number of young men from homelessness or, even worse, hopelessness. Roosevelt viewed his “boys” not merely as temporary relief workers, but as makers of a permanent, greener new America. Bursting with optimism, he believed the work-relief experience would transform the young recruits intellectually as well as physically. Teamwork and citizenship and conservation would all be learned in the CCC. Only 37 days after Roosevelt took office, the first CCC enrollee — Henry Rich of Virginia — was dispatched to Camp Roosevelt near Luray, Virginia, located in the 649,500-acre George Washington National Forest, the first camp to open. Six additional CCC camps soon followed in Virginia’s Shenandoah National Park, employing nearly a thousand men to thin overcrowded stands, remove dead chestnut trees, plant saplings, install water systems, build overlooks, and lay stone walls. Between 1933 and 1938, owing to New Deal care, state park acreage in America increased by 70 percent. When FDR became president, Virginia had only two state parks. Determined to rectify the recreation crisis, Roosevelt sent 107,000 CCC enrollees into the state, and within three years, six more parks would open.

Courtesy of The National Archives and Records Administration

Although the CCC actually started in Virginia, it was the trans-Mississippi West that the “boys” quickly occupied like an invading army. In the early and mid-1930s, perhaps the most notable CCC infrastructure work in the West was in Colorado, a state ideally suited for a youth corps. Only five states exceeded Colorado’s native forest acreage. Meanwhile, unemployment was at 25 percent. So in the summer of 1933, 29 CCC camps were established.

Many CCC recruits lived in the gateway town of Estes Park and rode red tourist buses (called “woodpeckers” by locals) up to the construction sites. It took six CCC companies, working on a dozen mountain peaks, to help turn FDR’s “Top of the World” road into a 48-mile reality. “A few months ago I was broke,” Charles Bartell Loomis wrote in Liberty magazine in 1934. “At this writing I am sitting on top of the world. Almost literally so, because National Park No. 1 CCC Camp near Estes Park … is 9,000 feet up. Instead of holding down a park bench or pounding the pavements looking for work, today I have work, plenty of good food, and a view of the sort that people pay money to see.”

In the state of New York, enlistment in the CCC began on April 7 and 8 with 1,800 young unemployed men, all carrying welfare agency certificates, showing up at the Army Building at 39 Whitehall Street in lower Manhattan. Cheers and renditions of “Happy Days Are Here Again” were heard. From the Wall Street area, these initial New York City recruits were bused to Fort Slocum in Westchester County, Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, and a segregated African-American CCC camp at Fort Dix in New Jersey.

Roosevelt ordered that half of New York’s 66 CCC camps were to be based in state parks. Four innovative New York CCC camps were erected on private land with the cooperation of the owners. Throughout the Adirondacks were numerous old dams, once installed for logging purposes but now collapsed, leaving flats overrun with sumps and bog vegetation. The CCC, by improving these old dams or building new ones, created nine new lakes.

Pennsylvania boasted the second-highest number of CCC camps of any state, trailing only California. Federally funded historical restoration projects took place at Fort Necessity and Valley Forge. Thirty-seven new fire observation towers were erected in state parks. Ickes, an ardent supporter of the NAACP, dispatched an African-American CCC company (led by black military officers) to landscape and renovate Gettysburg National Military Park with the hope that the experience would foster pride in the unit.

What Roosevelt hoped to do by employing youths, whether rural or urban, was to reduce juvenile delinquency. The New Republic went so far as to editorialize that the CCC was Roosevelt’s way to “prevent the nation’s male youth from becoming semi-criminal hitchhikers.” Education was a key component of the camps. Once the young men were officially enrolled, they would take classes in Forestry, Soil Conservation, and Conservation of Natural Resources. CCCers were further required only to do calisthenics, polish their shoes, brush their teeth clean, and maintain a sense of humor.

From inauguration day forward, Roosevelt ably projected the image of an open-hearted liberal who cared mightily about the downtrodden, struggling families, and the homeless. Increasing the size and scope of the federal government to alleviate suffering blindsided the GOP opposition. The CCC was part of this expansion. The public response was so favorable to the CCC that on October 1, 1933, Roosevelt instituted a second period of enrollment. Three months later, 300,000 CCCers were serving America. In 1935, Congress renewed the program, allowing participation to be over 350,000.

CCCers could initially sign up for only six-month stints. Later they could re-up for a total of 18 months, but after that time expired they had to leave the CCC for six months before they could reenlist.

When CCC acceptance letters arrived by mail or telegram or even word of mouth in Missouri, whoops and celebrations usually occurred. While there is no proper documentation of how precisely the CCC office in St. Louis selected the first 25,000 men from Missouri, a distinctive pattern emerged. Most Missouri CCCers were skinny as a rail, Caucasian, averaging an eighth-grade education, and lacking meaningful work experience. After passing a strict physical evaluation and receiving vaccinations, they were clay ready to be molded.

Within a year, over 4,000 CCCers, directed by the National Park Service, fanned out in 22 CCC camps and worked in 15 Missouri state parks, the majority in the Ozarks. A total of 342 examples of “rustic architecture” erected in these state parks by the CCC have been listed in the National Register of Historic Places as of 2015 — an astounding testimonial to the craftsmanship of the CCCers.

Tainting this fine record of achievement in Missouri, however, was the institutionalization of racial prejudice. Although Roosevelt had originally considered integrating the CCC, the program wasn’t sold to Congress as a civil rights crusade. Nor did he want to offend his Democratic political base in the South — which had been instrumental in his election — by attacking Jim Crow. Early on, the CCC created separate companies for African-American enrollees; 250,000 blacks enrolled in 150 “all-Negro” CCC companies throughout the nation from 1933 to 1942. The president’s uninspired “separate but equal” principle regarding the CCC infuriated civil rights groups.

Each Missouri camp had a company commander, a project superintendent, and an educational adviser. There were also chaplains, doctors, silviculturists (tree experts), agronomists, and engineers. At bugle call, the enrollees made their beds and scrubbed the barracks under the watchful eye of an Army foreman. Because the CCC had certain practices in common with the U.S. Army, it isn’t surprising that many military leaders, after initial skepticism, appreciated the CCC. Reserve officers were often in charge of a camp’s transportation needs, day-to-day management, and operational regulations. Part of the attraction of the CCC for many men was the seductive promise of three meals a day. Once the orange juice was downed and plates of eggs and sausage were consumed, the shovel-ax brigade climbed into the pickup trucks that drove them to work sites. At some sites, CCCers drove giant bulldozers and concrete mixers and wielded hydraulic rock-busters and electric saws. It’s been said that the CCC recruits in Missouri were more likely to stink of gasoline than smell of pine.

Not long after the CCC was established, the mushrooming camps each launched their own newspapers or mimeographed newsletters to chronicle daily life. Roosevelt asked Melvin Ryder — who had served on the staff of Stars and Stripes during World War I — to publish from Washington a nationally distributed weekly newspaper, Happy Days, which would feature propagandistic pieces on life in the CCC camps, sporting events, entertainment, and developments in conservation education. Happy Days sometimes printed entries for the best CCC motto. Many were funny, such as “They Came, They Saw(ed), They Conquered,” or bittersweet: “Farewell to Alms.” The New York Daily News approvingly quoted from Happy Days that the CCC motto was “They’ve Made the Good Earth Better.”

Even though the CCC was dissolved in 1942, the work of the “boys” remains visible from coast to coast. Over the course of its nine-year existence, the CCC conserved more than 118 million acres of national resources throughout America — more acreage than all of California. As the plaque at the School of Conservation in Branchville, New Jersey, reads: “These men participated in the world’s most famous conservation program. America will never be able to repay them. All that is great and good about conservation we owe to the CCC.”

From the Archive

Post Editorials Supported the CCC

The Post’s editorial board generally hewed to a conservative line. But when it came to the CCC, a program many on the right vilified as a socialist initiative, our support was wholehearted.

Better Than Welfare

All manner of schemes have been tried and very large sums have been spent for unemployment relief during the past three years. But no attack upon unemployment yet attempted has in it a greater element of hope and inspiration than the emergency conservation work of the Federal Government. This gives 250,000 men the opportunity of working for six months this summer in the nation’s parks and forests in return for food, clothing, medical attention, shelter and $30 a month, most of which the workers are expected to allot to their families at home.

Great numbers of young men have felt themselves a burden upon their families. Relief efforts in general have been directed to the unemployed married worker with dependents; the unmarried young men have been, until now, largely neglected. The forest camp work is aimed at these youths; its purpose is to redeem them from incipient social rebellion, to raise their depressed morale, to build up their health, to help their families with the allotments sent home, and incidentally to accomplish needed work in the forests and parks.

These young men will put in their six months under wholesome and uplifting conditions. They cannot fail to be better citizens for having spent that length of time in constructive manual labor in forests and parks. Nor can they fail to receive new hope and strength. After all, it is dreary business just to feed people and leave them in idleness. Details may prove thorny, but the idea is definitely promising and the attack upon the problem of idle youth is strategic and direct.

—“Hope for Young Men,” Editorial, June 17, 1933

Self-Respect, Confidence, and Fortitude

How might morality be strengthened in the individual? Above all, by strengthening courage; therefore, proximately, by developing hardiness and health; a fit and ready body is a sturdy prop to self-respect, confidence and fortitude. How admirable it would be if the Civilian Conservation Corps would raise its remuneration, widen its purposes, and draw every American youth for a year into its character-forming discipline, its wholesome friendship with forest, stream and sky!

—“Our Morals,” by Will Durant, January 26, 1935

Some Mistakes Were Made

Recent admissions that political influence has been a factor in selecting part of the CCC personnel are exceedingly distasteful to large numbers of fair-minded and unprejudiced people. … Surely, in the hasty finding of work projects for nearly half a million young men, it is more than likely that some mistakes were made. But the idea of putting hundreds of thousands of otherwise idle youths into wholesome outdoor work amid healthful and often beautiful and inspiring surroundings has appealed to everybody.

—“The Trail of the Politician,” Editorial, September 5, 1936

The Right to Write

Benjamin Franklin, founder of The Pennsylvania Gazette (predecessor of the Post), famously championed freedom of speech and an unbiased free press. He held that any man’s point of view, however unpopular, should be worthy of discourse. As he wrote in the May 27, 1731, edition of the Gazette:

“Printers are educated in the belief, that when men differ in opinion, both sides ought equally to have the advantage of being heard by the publick; and that when truth and error have fair play, the former is always an overmatch for the latter.”

Wise words. Over the years, Post editorials have continued to offer perspective on the subject of media bias and freedom of the press. Click on the blue headlines below to read related articles from our archive.

Free Speech

In April of 1934, the Post was concerned about the way President Franklin D. Roosevelt regarded the press’s right to freedom of expression. In the editorial “Free Speech,” the Post cautioned against an expansive, controlling administration and reasserted the prerogative of the press to safeguard the necessity of free speech and checks on government power.

Bias at the Top

“Today’s Press is ‘Freer’ Than Greeley’s,” written on August 14, 1947, argues that the notion of freedom of the press is not nearly what it seems, and that many media outlets are not as privy to that safeguard as they should be.

Fair and Balanced Reporting

On September 24, 1966, the Post ran an editorial titled “Beware of Self-Censorship,” analyzing the press’s role in covering courtroom cases and cautioning the media against inciting a perhaps undeserved trial by the court of public opinion.

The Impact of Television

On October 29, 1960, Pulitzer prize-winning journalist Harry Ashmore wrote in the editorial, “Has Our Free Press Failed Us?” that we don’t know, and haven’t known for a long time, where journalism ends and entertainment begins.

Time for a Third Party?

In the past year we’ve watched Washington, D.C., freeze into paralysis. The wheels of government have nearly ground to a halt as Congress barely even agreed to provide the money for spending already required by laws it had earlier passed. And the inhabitants of the two sides of the political aisle bitterly blame each other. Ask Republican Congressman Allen West who’s at fault, and he says the Democrats who have “a vicious propaganda machine. It espouses lies and deceit.” Ask Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, and it’s entirely the Republicans who stop all progress with “obstructionism on steroids.” Ask the American people, and they agree with both; according to at least one recent poll, they blame the two parties equally. There seems to be something fundamentally wrong with our two-party system.

In fact, passing the buck seems to be the only thing the parties can agree on right now. They each agree that the other party is broken. So it’s hardly surprising that there is serious talk of a third-party presidential candidacy this year. Ron Paul, the libertarian Texan, has suggested he may run on his own if he doesn’t win the Republican nomination, and an outfit called Americans Elect has worked quietly but diligently to make sure the paperwork has been done to assure that some third-party candidate can run in all fifty states. Almost everyone is fed up with Democrats and Republicans.

Are we on the verge of the collapse of the two-party system? You might think so, but it has been amazingly resilient, surviving through catastrophes as great as the Civil War and the Depression. The last time a president was elected who wasn’t a member of today’s Democratic or Republican party was in 1848. “E Pluribus Unum” says the motto on the Great Seal—“Out of many, one.” Maybe that should be “Out of many, two.” A recent Gallup poll found that 31 percent of Americans identify themselves as Democrats and 27 percent as Republicans. Considerably more—40 percent—are independents, disdaining both parties. But that leaves only 2 percent to belong to any other party out there.

How did it get this way? Can it really last much longer? And what, at bottom, do the two parties stand for?

At the very beginning, the founders didn’t want parties, yet we’ve had them almost always since. There seems to be something basic to both human nature and our political system that makes us split along either/or lines. Those either/or lines have shifted and drifted over the centuries, but they’ve almost never not been there.

The electoral college elected the first president, George Washington, in 1788 unanimously. He was so indisputably the right choice that no other candidate was even imaginable. Yet by the time he delivered his farewell address in 1796 near the end of his second term, national unity had so ruptured into two battling sides that he felt compelled to warn of “the alternate domination of one faction over another … a frightful despotism” that would bring “disorders and miseries.” Thomas Paine, on the other side of the new political divide, responded that “the world will be puzzled to decide whether you are an apostate or an impostor, whether you have abandoned good principles, or whether you ever had any.” And that was George Washington he was talking about. The parties have been at each other’s throats since the very start.

At the heart of that gulf, then just as today, lay a tension between wanting a relatively big, active government and wanting a small, unthreatening one. Washington and Alexander Hamilton, his first secretary of the treasury, were among the champions of a nation of strong, well-enforced laws that actively worked to encourage banking and manufacturing and trade. On the other side, Thomas Jefferson idealized a land of free, independent farmers whom government would touch only with the lightest hand. Hamilton’s side became known as Federalists, Jefferson’s as Democratic-Republicans. In 1796, in the first contested presidential election, Jefferson faced off against the Federalist John Adams. The law then stated that whoever got the second-most votes became vice president, so Jefferson had to end up awkwardly serving as his political enemy’s second-in-command.

In 1800 Jefferson won the top job, and in his inaugural address he expressed the hope that the two-party system could become a thing of the past, saying, “We are all Republicans. We are all Federalists.” No such thing happened. However, the Republicans had the upper hand for quite a while, winning the next five presidential elections. The Federalists came to seem elitist, and by 1828 they appeared to be withering away. But in the election that year the Democratic-Republicans split into two factions, creating what became the two parties of the next several decades. Andrew Jackson won in 1828 under the banner of a new Democratic party. He was frontier-born and a war hero, a man of the people, a strong upholder of individual liberties against institutions such as a national bank—and the farthest cry yet from the kind of Virginia aristocracy that George Washington had personified. Jackson’s party grew into the Democratic party we still know today. The other party, the Whigs, was the remnant of the Federalists and less populist Democratic-Republicans.

That pairing lasted until the 1840s when the issue of slavery poisoned everything. Think there’s a lack of civility in politics today? Emotions about this issue grew so violent that when Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts angrily denounced slave owners in 1856, Representative Preston Brooks of South Carolina beat him almost to death right on the Senate floor. The Whig party split apart and crumbled in the 1850s. After a flurry of short-lived parties with names like Free-Soil and Know-Nothing flared up and died, a new anti-slavery party emerged: the Republicans. It elected its first president, Abraham Lincoln, in 1860, and it survives as the Republican party of today.

And so the two parties we still know—Andrew Jackson’s Democrats and Abraham Lincoln’s Republicans—were already in place 150 years ago. They have evolved and changed continually, though. Throughout the rest of the nineteenth century, the Republicans were the party of business and of relatively strong centralized government power, partly because the opponents of slavery had tended to be prosperous citizens of the industrialized, urban North. Meanwhile the South became overwhelmingly Democratic, in opposition to the party that had risen from the antislavery movement. The Democrats were the party not only of the white-dominated South but also of states’ rights and small government and rural interests.

From time to time events shifted the two parties and their relative power. At the turn of the twentieth century a “progressive” movement grew up that sought to clamp down on big business. A Republican progressive, Theodore Roosevelt, served as president from 1901 to 1909, and the Democrats elected their own progressive, Woodrow Wilson, in 1912. But in the boom years of the 1920s, old-fashioned business-friendly Republicans took charge again—until the crash of 1929 and the Depression.

By 1932 Republicans had held the White House for 11 straight years, but the Republican-led boom had turned into a Republican-led bust, and in the depths of the Depression the nation elected a Democrat, Franklin D. Roosevelt, who would serve until his death in 1945. There would be a Republican in the White House for only eight years between 1933 and 1969. Roosevelt won all but two states in 1936, and the Republican Party appeared to be all but dead.

As the nation fought a world war and climbed out of the economic depths, however, the Republican party slowly healed its wounds. It almost won the White House in 1948 when the Chicago Tribune ran its infamous mistaken “Dewey Defeats Truman” headline. It did take the presidency in 1952, electing the greatest military hero of World War II, Dwight D. Eisenhower. It barely lost to John F. Kennedy in 1960.

The 1960s were a time of tumult for the two parties just as they were for America as a whole. The Vietnam War drove a Democratic president, Lyndon B. Johnson, to announce that he wouldn’t run for reelection in 1968, and the agonies of the Civil Rights movement, which he had championed, led many white Southern politicians to abandon the Democratic party just as they had swept into it a century before. From 1969 to 1993 there would be a Democratic president for only four years, during the single, luckless term of the last of the powerful Southern Democrats, Jimmy Carter.

Today the same two parties still dominate the political world in the U.S. The Republicans are broadly seen as the party of business and of less rather than more government action and regulation. The Democrats remain the standard-bearers for organized labor and the entitlements that grew up with Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. The Democrats are generally considered the stronger party among blacks and other minorities as it has been since the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s (and it had been gaining ground among those minorities earlier), but since race is a much smaller part of our national politics than it once was, that is less of a defining difference now than in the past.

Why are the parties getting along so terribly right now? It hasn’t always been this bad. They have sometimes seemed especially polarized and antagonistic but sometimes quite similar and cooperative. They grew somewhat alike during the progressive era; they were bitterly opposed during the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt and the New Deal. They had much in common during much of the late twentieth century when Republican Richard Nixon carried on some of the Civil Rights initiatives of Democrat Lyndon Johnson and when Democrat Bill Clinton realized some of the welfare-limiting and budget-balancing dreams of Republican Ronald Reagan. Basically, they have tended to move closer together when economic times are good and there is less to drive them apart. Since the Great Recession began in 2008 and economic times turned bad, they have been as sharply divided as ever.

What lies at the base of all their differences, beneath all the individual policy matters they face off about such as abortion and immigration policy and tax breaks for the wealthy and so much else? And what has made them endure for so long? Why do we have two parties instead of three or four or more? There is probably just one answer to all these questions: The parties, at bottom, represent fundamentally opposed basic concepts of government. They stand for government as either essentially good or essentially bad. Americans who believe that government can and must be a powerful force for good tend to be Democrats. Americans who believe that government gets in the way more often than it helps, that it should be as limited and small as possible, tend to be Republicans. Before Franklin D. Roosevelt, Democrats were more the small government party and Republicans the big government one; Roosevelt’s New Deal and the rise of the broad government programs we have had ever since turned that around. The shift of the South from Democratic to Republican in the 1960s and 1970s cemented that change.

However, as dangerously and irreconcilably divided as the parties seem right now, they’re almost certainly not about to crumble. In fact, the sharpest rift right now may be within one of the parties, the Republicans. Since the rise of Tea Party power in the 2010 elections, the Republicans in the House of Representatives have been embattled among themselves, with speaker John Boehner struggling endlessly—often hopelessly— to get them to agree on anything. Similarly, the lead-up to the 2012 Republican primaries has been marked by a stubbornly unyielding polarity between staunchly conservative and Tea Party-favoring candidates like Michele Bachmann and more moderate ones like Mitt Romney. It may be that the Republican party will soon redefine itself, as both parties have so often done in the past, but there’s nothing happening to suggest that we’ll soon have three or four major parties.

Why? Because so much of what people disagree on comes down to that basic tension between big, strong government and small, limited government. And that tension can probably never be finally resolved, at least in a nation that is based on free enterprise and individual liberty and initiative—and that is also based on equal opportunity and equal rights and fairness for all. The division between left and right will probably be with us always. In fact, it has become so central to our national psyche that I’d suggest another way of looking at the great divide, by seeing us all as a great American family with a timeless family dynamic.

If indeed we are in any sense a national family, then maybe, just possibly, in an abstract sense, within that family Republicans are our father and Democrats are our mother. I mean this: Your stereotypical father protects the home fiercely but also expects his children to be strong and resilient and self-reliant and to learn by tough love and end up looking out for themselves, just as Republicans are stereotypically strong on defense and weak on coddling. Your stereotypical mother builds the nest and is nurturing and gives everyone their meal and wants all the children to embrace love and fairness, just as Democrats focus more on supporting workers and striving to lift up the poor and the struggling. It’s no coincidence that it’s mostly Republicans who attack “the nanny state” and Democrats who warn, “Big Brother is watching you.” These are of course clichés, both about mothers and fathers and about Democrats and Republicans. But doesn’t every cliché contain a grain of truth?

And if there is a grain of truth here, then I’d add that just as the traditional ideal of a strong family has two parents, a mother and a father, then perhaps also our nation does best with two parties, Democratic and Republican. They may fight noisily from time to time, but who would have it any other way? Who wouldn’t want to have both kinds of love and care and moral passion? We need them to balance each other and show us the whole range of love and support. The system, like any marriage, and even the institution of marriage itself, may be far from perfect, but what else could possibly be better?