Is Public Opinion Polling Accurate? A Look at Gallup, Then and Now

Many people were shocked by the outcome of the 2016 election. Donald Trump’s win was so unexpected that Americans assumed public opinion pollsters had been equally surprised. Surely at least some of the pre-election polls should have predicted a Trump victory. The notion began circulating that the polls had misread the country. In fact, they hadn’t.

Up to the day of the election, the polls gave Hillary Clinton a three percent lead, which is what she achieved in the final count of the popular vote. However, Trump gained enough electoral votes to beat that slim lead. Furthermore, the election results were within most polls’ margin of error.

Yet doubts remain. A recent Hill-HarrisX poll reported that 52 percent of Americans are doubtful of poll results they hear in the news, 29 percent don’t believe most, but trust some, and 19 percent almost never believe in polls’ accuracy. (If you can believe this poll.)

Despite doubts, studies have shown that well designed polls are accurate. In addition, polls serve an important role: they reflect the voice of the people. Lydia Saad, director of U.S. social research at Gallup, says, “The goal of polling is to amplify the voice of the public. If we ever lost this ability to sample America’s opinions, it’d be surprising how lost we’d feel. We wouldn’t know what people are thinking, and we’ve have to rely on unreliable sources.”

Unreliable sources are all that America had for years. Before George Gallup began gathering opinion data in the 1930s, politicians relied on such things as newspaper editorials, letters to the editor, and the frequency of labor strikes to read the mood of the people.

When Gallup began taking surveys, his group conducted door-to-door in-person interviews in select locations chosen to be representative of the whole country.

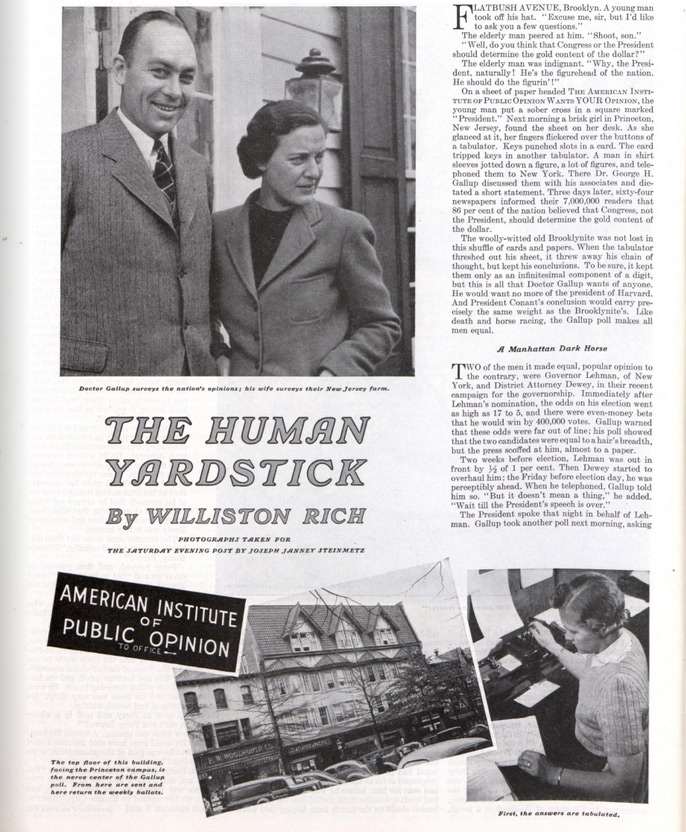

Telephone polling made it much easier to obtain a true random sample of the country. But there were doubters, as the Post reported in 1939 in “The Human Yardstick.” Gallup had predicted that President Roosevelt would certainly be re-elected in 1936. Republican newspaper editors challenged his assertion, making an argument pollsters have often heard over the years. “It can’t be a national poll. I haven’t received a ballot. What’s more, nobody in my neighborhood has!”

And though critics may still say this about polls, the facts are that public opinion polls have only become more accurate over the years. “We use well defined methods based on randomization,” says Saad. “We pick random subjects so that everyone has an equal chance of being in the pool of data.”

Many polling organizations, including Gallup, have increasingly relied on conducting surveys by cell phone. Today, cell phone calls account for 70% of Gallup’s data, and this percentage is still rising.

Polling methods vary somewhat based on the polling organization, but Gallup’s “live” (telephone interview) polling is the most common. The pollsters purchase phone lists generated from blocks of area codes and exchanges known to be assigned to cellphones or household landlines and then randomly generate the last four digits.

“We’ll call, and if we don’t reach anyone, we’ll call back. To get a representative sample, we need to include people who aren’t home very often,” Saad explains.

The raw data is then weighted to get a sample that matches census statistics for five criteria: age, race, region, gender, and education.

One of the more frequently challenged polls Gallup conducts is the presidential opinion poll, which is often accused of being biased. “Our procedure has been standardized since the days of President Truman,” says Saad. “For example, when we reach one of our subjects, we first ask them if they approve or disapprove of the president’s performance. Only then do we ask about other issues like the environment, healthcare and so on, because we find that asking about these issues first can change the subject’s opinion about the president.”

Even though polls aren’t perfect, they are currently the best way to measure public opinion. “If the public decides polls are bad and stops answering them, it will be hurting itself in the long run,” says Saad. The alternative is to rely on commentators or online information. “And there’s no way to gauge the accuracy.”

Featured image: Shutterstock

Do You Really Want to Live to 100?

A man asks his doctor how to live to be 100.

The doctor asked the man, “Do you smoke or drink?”

“No,” he replied. “Never.”

“Do you gamble, drive fast cars, or fool around with women?” inquired the doctor.

“No, I’ve never done any of those things either.”

“Well, then,” said the doctor, “why do you want to live to be 100?”

It was a question that might have occurred to pollster George Gallup as he concluded his 1959 study “The Secrets of a Long Life,” for The Saturday Evening Post. (Read the full story here.) For the report, the Gallup Organization had spent months interviewing 402 Americans from across the country who had all lived 95 years or longer.

When all the data was collected, Gallup drew two surprising conclusions.

First, if you wanted to live to a very ripe old age, it didn’t matter what you ate or drank or how much you exercised.

Second, you’ll live a lot longer if your life is dull.

Nothing helped the human body reach a ripe old age better than an unexciting life of regular habits, little variation, and low stress. The interview subjects weren’t motivated by driving ambitions. They hadn’t even tried to achieve a long life. (Only 9 percent of the group had ever expected to reach their 90s.) “For many,” Gallup wrote, “their only outstanding accomplishment is that they have lived longer than most other humans. … Living to be old is probably the most exciting thing that ever happened to these people.”

They were admirable people, Gallup argued: honest, hardworking, law-abiding citizens and parents. But these elderly men and women had shaped their lives for contentment, not achievement. They were not risk-takers. When the great tide of migration swept westward, they remained where they had been born—usually in a small town.

In their lifetimes, stress wasn’t the buzz word it is today. They might have talked instead of discomfort, worry, nerves—whatever the word used, these subjects had figured out how to avoid it.

“If this still sounds dull,” Gallup concluded, “the chances are that you’ll never make 90.”

Gallup had commenced his research by asking subjects if they could attribute their long lives to any one factor. Fully one-third of the subjects said, “I don’t know.”

Others offered these explanation:

• God’s will (22 percent)

• Adaptability and a good sense of humor (17 percent)

• Hard work (16 percent)

• Good genes—parents or siblings who lived into their 90s (11 percent)

• Keeping regular habits (9 percent)

It shouldn’t surprise you to learn that most of the interview subjects lived lives of moderation—they didn’t eat or drink to excess, and they didn’t smoke. But a significant minority broke these rules.

In 1959, William Perry, 106, of San Francisco had ham and eggs, beans, fried fish, and coffee for breakfast.

Take the issue of drinking, for example. Over half of the people interviewed had never touched liquor in their lives, which might seem like an argument for abstinence. And yet, there was 115-year-old Uncle Charley Washington who, throughout his life, had drank “as much whiskey as he (could) afford.” Also, there was the testimony of 101-year-old Mrs. Marie Renier. For 80 years, she had drunk a quart of whiskey, and in many decades, as much as a gallon of beer a day.

As for food, there’s no consistent answer, either. Some ate lean, others ate richly. Meals tended to be heavy on the starch and protein. If a vegetable made it to their table, it was usually overcooked. Half of them had eaten fried food regularly all their lives.

Overall, there was enough contradiction among the subjects’ answers, aside from the uniform dullness, to rule out any other “secrets” for extending lifespan.

Even adopting a healthy pattern of living—regular hours, healthy diet, regular exercise, etc.—was no guarantee. As Gallup noted, “the only apparent value of their testimony is to give some sort of comfort to those of us who do not conform to the pattern and who covet long life.”

In other words, no matter what rules you lived by, you still had a chance at long life. And if you had followed all the generally accepted rules for good health, you still had no guarantees you’d make it to 100.

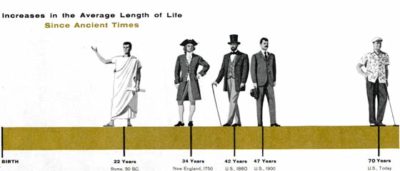

Americans today have a one-in-6,000 chance of living 100 years, which is probably why there are more centenarians living in America than any other country. We of the modern age still believe we can improve our odds with a better diet and more exercise. But if the real secret is living a life that is horribly, painfully dull, would any of us truly want to live to 100?

when the Gallup articles were published in 1959

and 78.5 in 2012.