The First “Official” Kennedy Conspiracy: Fifty Years Ago

The internet will be abuzz with fresh conspiracy theories this fall.

On October 26, the National Archives is scheduled to release 3,600 classified files related to the assassination of President John Kennedy. Another 35,000 are awaiting review and release.

Only the president has authority to keep the files restricted beyond October.

According to a Politico article, staffers at the National Archives who have been sorting the papers say they’ve discovered no bombshell revelations in what they’ve seen.

A number of sealed files from the CIA and FBI were released in 1991, after the movie JFK renewed public fascination with Kennedy’s death. These documents indicated that Lee Harvey Oswald had visited the Cuban embassy in Mexico City in 1963 and talked openly of killing the president. One expert suggests the remaining files were locked away to protect the agents who failed to apprehend Oswald when they learned of his plans.

Americans of 1963 would probably be surprised to hear that the death of their president would still be topic of heated debate 54 years later. In those days, there was little talk of conspiracies and multiple gunmen. In 1967, only 36 percent of Americans believed Oswald didn’t act alone.

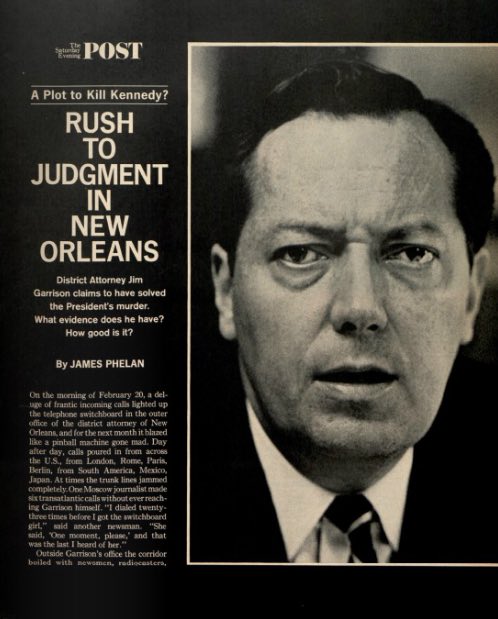

But that same year, New Orleans District Attorney Jim Garrison announced that Kennedy’s murder was the result of a conspiracy. “My staff and I solved the assassination weeks ago,” he claimed.

Reporters swarmed to New Orleans to get the story from Garrison. He turned down most requests for interviews but made time for Post reporter James Phelan. Garrison told Phelan “the whole incredible story,” recounted in “Rush to Judgment in New Orleans” from the May 6, 1967, issue of the Post.

Garrison’s conspiracy theory rested on the testimony of a witness who had come forward, Perry Russo. Questioned under the influence of drugs “to refresh his memory,” Russo claimed to have seen three conspirators plotting to kill Kennedy: David Ferrie, Clay Shaw, and Lee Harvey Oswald.

Both Ferrie and Shaw denied such a meeting. Four days later, Ferrie died from a brain hemorrhage, which suggested, to some, that he’d been silenced.

In his article, Phelan seems skeptical of Garrison’s judgment and his witness’s reliability.

For example, Dave Ferrie, whom Phelan calls an “exotic loser,” is described by Garrison as “one of history’s most important individuals.”

Also, Garrison claimed the murder of the president was “the result of a homosexual conspiracy masterminded by Dave Ferrie” who wanted “the thrill of staging the perfect crime.” At this early stage, there is no mention of the CIA, Cubans, the Mafia, or any other possible conspirators.

Phelan saves his biggest misgivings for the end of his article.

He notes that Russo only remembered seeing the conspirators after he’d been coached to remember under drugs. Andrew Sciambra, Garrison’s assistant D.A., said no, Russo had remembered seeing the conspirators before, in the very first interview. Sciambra simply forgot to write it down.

“‘You made notes when you first talked to Russo,’ [Phelan] said. ‘Your original notes would show whether he mentioned an assassination plot.’

“Sciambra said he had burned his notes.”

In March 1967, Garrison charged Shaw with conspiracy to kill the president. The trial didn’t start until January 1969. By that time, Garrison had broadened the conspiracy to include the CIA, to whom Shaw had occasionally provided information about international business.

Three months after the trial began, the jury took less than an hour to acquit Shaw. To date, he remains the only person every brought to trial for Kennedy’s killing.

Of course, the matter did not end there. Until his death in 1992, Garrison persisted in his claim that a conspiracy killed President Kennedy.

His search has been taken up by a growing numbers of Americans who hunt for evidence of a conspiracy. Today, 70 percent of Americans believe Oswald did not act alone, according to a 2003 ABC News poll.

The release of several thousand files of official reports is unlikely to answer all conspiracy questions to everyone’s satisfaction, and will no doubt spawn many new theories.

Featured image: May 6, 1967, cover of The Saturday Evening Post, illustration by Fred Otnes (SEPS)