Boxing’s Great What-If: Jack Dempsey on the ‘Long Count’

Alternative sports histories are nearly as popular as the sports themselves. Fans love to consider (and argue over) the effects of the ultimately unknowable “what-ifs” of sports. For example:

The most intriguing what-ifs concern the alternative histories of a sport. For example:

- What if Boston hadn’t sold Babe Ruth to New York, or if Ruth had continued playing as a pitcher?

- What if Jackie Robinson had never been allowed to play in the whites-only major leagues? Or what if the racial barrier had been breached before World War II, and renowned white batters had faced black pitchers like the phenomenal Satchel Paige?

- What if basketball hadn’t lost Bill Walton or Penny Hardaway to injuries?

- What if Muhammad Ali hadn’t had his boxing license suspended for civil disobedience during his late 20s?

- What if Bill Buckner hadn’t missed that ground ball in the 1986 World Series?

One of the great never-to-be-settled what-ifs involves the 1927 Dempsey-Tunney heavyweight championship fight and the infamous “long count.” On September 22 of that year, more than 100,000 boxing fans crowded into Soldier Field to see Jack Dempsey try to win back his heavyweight title from Gene Tunney.

In round seven, eight rapid hits from Dempsey sent Tunney to the mat. Usually, Dempsey would stand over his fallen opponent, ready to beat him back down. But a new rule required boxers to go to a neutral corner before the referee would start counting their opponent out.

Forgetting this, Dempsey remained beside Tunney. The referee finally shoved Dempsey to a corner and only then began his count — nearly five seconds after Tunney fell. At count “nine,” Tunney rose to his feet. Those extra seconds became known as the “long count.” Tunney later claimed he could have regained his feet early in the count, but took the extra time to recover. And Dempsey said he had no reason to doubt him.

When fans read about the match in 1927, they believed Dempsey was robbed. Only when films of the contest were released in newsreels did Americans see that the count was not as long as they’d imagined. But some fans held onto the idea that, with a proper count, Dempsey would have won with a technical knock out.

Boxing aficionados continue to speculate about what might have been. In the Post four years later, one man with a unique perspective on the fight weighed in: Jack Dempsey himself. In “In This Corner,” although he recounts the fight and the events surrounding it, he hardly lays the controversy to rest. He does, however, take a broader, more pragmatic view of his life as a boxer and of that fight in particular.

In This Corner

by Jack Dempsey

Excerpted from an article originally published on August 29, 1931

Following my knockout victory over Jack Sharkey, Tex Rickard immediately propositioned me for another match with Gene Tunney.

“The old iron is hot again, Jack,” Tex said to me. “Now is the time to strike. This win over Jack Sharkey puts you right out front with Tunney himself. You laughed at me a few years ago when I told you that we would draw $1,000,000 with the Carpentier fight. Laugh at me now, if you dare, when I tell you we’ll draw at least $2,500,000 with you and Gene in the ring again.”

Who can know but that man who has lived through the experience what it means to wonder whether you are good or bad? I had every reason to feel I had been a great fighter. I hadn’t as yet had incontrovertible evidence that my day was gone. The old fighting heart and the old fighting instinct throbbed within me for expression. I hated the thought of anybody else in possession of my heavyweight championship. I reasoned the thing out very carefully in my own way; thought it out when I was alone at night with none to bother me.

There was one thing which seemed certain to me. That was that I would knock out any man I hit right. What if my legs had slowed up a trifle? What if the old zip and speed were gone from my bobbing and weaving? These things must essentially be offset by experience and by knowledge. I felt strong as an ox, and because most of my contests had been short, I had never really taken any serious beatings. Why, then, should I not gamble that at least once in 10 long rounds I could tap Gene Tunney on the chin, or under the heart, with a punch that would win me back the heavyweight championship of the world? There was no good reason to suppose such a thing unreasonable. I felt that I could hit Gene; felt that I could plan out a campaign of battle that sooner or later would bring him to me for that one lovely punch.

With this in mind, I considered the possibility of a $3,000,000 box office. Aside from the money that would establish Tunney and myself as the greatest financial figures boxing had ever produced, I was a comparatively rich young man when these problems presented themselves. I could have retired then as easily as I retired later, and lived on my income.

So it was not entirely money by which I was actuated. There was — and I do not say it sentimentally — an appreciation and a love for the sport of boxing which superseded in my calculations every financial angle. I think, perhaps, I was a big kid who had lost a toy and wanted to fight to get it back again. In any event, I told Tex Rickard to match us and I promised myself that I would give Gene Tunney a whole lot better fight than I had given him that rainy night in Philadelphia.

My contest with Jack Sharkey netted me almost $500,000 and, to put it in the jargon, I was sitting pretty, financially. There was nothing between me and retirement other than a determination on my part to satisfy that hankering wonderment as to my own condition. I knew perfectly well that I wasn’t 30 percent of the old Jack Dempsey the night I lost my heavyweight championship. On the other hand, I knew perfectly well that Gene Tunney was a fine fighter and a whole lot better than the public has ever given him credit for being. There lay the problem.

I knew that my win over Sharkey indicated that I was in fair physical condition. I felt that a good training siege would put me back in excellent condition. Furthermore, I was perfectly certain that when I was in condition, the man did not live who could box me 10 rounds without at some time or other being hit on a vital spot. I knew perfectly well, as I have said, that anyone I hit on a vital spot was very apt to be counted out. That was my bet on the Tunney fight at Chicago. I believed that the worst I had was a 50-50 chance to regain the championship, and that is exactly the right percentage for a great fight.

I went to Chicago to train. Leo Flynn once again took charge of my training and acted in the capacity of chief adviser. I think that most of the fellows who realized my condition before the first Tunney contest favored me to win over Tunney in the second. There were all sorts of rumors floating about my camp to the effect that the gamblers had everything set against me once again. This time I did not easily fall for those rumors.

No Fixers Wanted

I had been knocking around the $1,000,000 gates long enough to know that a good many shady things were attempted. But I also had seen enough of Gene Tunney to know that it was not in his mind or his heart to fake a championship prizefight. This absolute confidence in Gene gave me the greatest weapon I had to use against the fixers who later approached me.

It is not easy to sit here and write these details. I feel that I must do it, however, in justice to myself and in justice to Gene Tunney. I have often hoped, to be truthful about it, that Gene would write his life experiences. I certainly would like to read them and get the other side of our two contests. In my own relation of events, I have stated the absolute and simple truth just as closely as I know how. I know that Gene would do the same thing. Out of a contrast of the two stories a pretty situation ought to develop.

I positively was approached by people in Chicago. I was, in fact, told that for $100,000 I could win the heavyweight championship. I laughed in their faces for a good many reasons, the principal ones of which I am going to relate. They are so obvious and so indisputable that none can deny them.

First, I refused because I had planned a careful campaign against Gene Tunney and believed that I could beat him on the level. Second, I never would trust anybody who would take or give a bribe. Third, I have never faked a fight in my life and I never will. Fourth, even if I did lose my head and pay such a craven bribe, I knew nobody could fix Gene Tunney, and Gene Tunney was the man I had to fight. Next, despite the advice of some people who harassed Leo Flynn and myself, I felt that my coming contest with Gene was the last I ever would fight, win, lose or draw.

If I won, I planned to retire undefeated. If I lost, nothing more need be said. So I laughed in their faces when they made me this proposition.

The fight itself has hardly wilted sufficiently in the public memory to warrant a detailed description here. I went into the ring planning to work on Gene much after the fashion I had worked on Jack Sharkey in my last contest. In Tunney, however, I was fighting a better fighter than Sharkey. I do not wish to be unkind in that statement; I merely state the fact.

Down for the Long Count

No matter what happened, Gene remained as calm as a mill pond. At times, his machine-like perfection was maddening to me. That darting, straight left jab of his, coupled with an inside, straight right cross that had great jarring possibilities, sufficed to fill anybody’s evening with bouquets that were loaded with reverse English. Gene could fade away from an attack and at the same time hook a jarring left to the liver as well as any fighter who ever lived. So I did not fight him exactly as I had Sharkey. I took more precautions. I felt from my first experience with Tunney that he would draw the lead from me and counter. I planned my campaign entirely on that supposition. It worked out perfectly.

Just as I had planned, I finally got my shot at him. The rest is history. The fact that it is disputed history is of no vital importance at this moment. I have stated previously in my story what Tex Rickard said to me on the afternoon I boxed Georges Carpentier. He told me that I was the sort of a kid to whom things happened.

There are people like that, and I am confident that I am one of them. Even in my present activities, events can run along at a fight club in the even tenor of their way, show after show after show. But let me appear in the capacity of referee and the unusual happens. This has recently been true twice in Madison Square Garden at New York City. It was true the other night in Los Angeles. It seems to me to be true wherever I go. It certainly was true that night in the Chicago Stadium when I caught Gene Tunney in a corner of the ring and knocked him down for the historic “long count.”

If anyone thinks that I am here to express any opinion as to the merit of that “long count,” they have another think coming. All I have to say about that hectic contest is that I fought the best that I knew how to fight. I put into that battle everything that I could summon in the lexicon of physical equipment and experience. When I cornered Gene and knocked him down, I felt the exultance that came to me that July Fourth in Toledo when I won the championship from Jess Willard. Gene was down, and, boys, he had been hit! A look at the motion pictures of the battle will indicate just how many punches Gene absorbed as he toppled over there against the ropes.

I want to say something else in terminating my story. Gene Tunney, on the floor of that Chicago ring, showed the world more of the stuff of which a champion is made than he did in the entire fight at Philadelphia. I don’t think Gene even knows how to spell quit, and I don’t think he’ll ever learn how to spell it. He has the equipment and the heart of a champion. Had he not, he never would have got up off that ring floor in Chicago inside a hundred count.

All the way through that contest, I figured it a hard-fought and close one. After Gene had got up, following that knock-down, he gave a great exhibition of thinking under fire. I could not catch him for the rest of the round to land a finishing punch. But I kept right on trying in the next round, and as a result of my over-anxiety, Gene dropped me to my knees for a count of one.

It was a red-hot fight, and I don’t think anybody could criticize the performance of either of the contestants. Gene won the decision and remained heavyweight champion of the world. To say that I was not disappointed would be to tell a lie. I was disappointed. But once again I had collected a modest fortune for my efforts, and there was a good deal in my life to console me for the missing heavyweight championship.

After the Fight

There was a home and a wife in Hollywood. There was plenty of money in the bank to take care of me and the family I had caused so much worry in my younger days. There was the Firpo fight, the Carpentier fight, the Fulton fight, and several others which had marked the very peak of thrills for the boxing public. Of none of these need I ever be ashamed. After all, that man who wins a championship should be content. He should not expect to hold it over the hurdles of the onrushing years.

In my dressing room after the second Tunney contest, I was momentarily dejected. As is always the case with dressing rooms, a great many people I did not know managed to crowd in. I presume this is curiosity on their part, and it may be morbid curiosity. A fighter, in defeat or victory, is much like a monkey in a zoo to those who can get close to him. They want to look at your eyes and your ears to see how badly you may have been injured. They want to pick up a word here or a gesture there which, later on, they can relay, magnified, to their own little public.

I have always regarded these curious fans in a tolerant, even friendly way. They are, I presume, out of the great masses which support professional boxing. But I never had come to regard them seriously, nor did I ever expect to receive from one of them a perfect gem of philosophy. But I did.

It came from an emaciated chap weighing not more than 130 pounds, in high boots and an overcoat. I never will forget him. He had a hooked nose and sharp little eyes that winked incessantly under thin, scraggly eyebrows. He was smoking a cigarette when first I saw him, puffing a cigarette and looking intently at me.

I sat down on the edge of a rubbing table and my handlers began removing the bandages from my fists. The little chap wore a brown suit and shifted uneasily from foot to foot. He smoked jerkily at his cigarette, inhaling nervously and blowing the smoke upward so that it curled under the brim of a shabby, brown felt hat.

What’s a Championship?

I noticed, for no particular reason, that his fingernails were in deepest mourning about their tips. I grinned at him and winked. He took the gesture as a personal salutation which seemed, from his expression, to illuminate his life.

“Okay, Jack,” he called to me.

I grinned and winked again. Newspapermen crowded about, but they did not get between us. The little stranger saw to that. One of the newspapermen said:

“Jack, do you realize that Tunney was down for 17 seconds?”

“No,” I said. “I don’t know how long he was down.”

“Why didn’t you go to a neutral corner?” the newspaperman demanded.

“I meant to,” I admitted, “but there didn’t seem to be any hurry about it. The count had started and I thought it would continue.”

One of my seconds growled: “He’s still champion of the world, ain’t he? How many times do you have to count a guy out to win? Seventeen seconds!” Some other newspaperman spoke up, “It was only 14 seconds,” he said.

“Well,” my handler growled, “up till tonight, 10 seconds has always made a champion! I’m tellin’ you guys right now that, with the great majority of American boxin’ fans an’ with everybody who knows anythin’ about the prize ring, Gene Tunney got a decision tonight, but Jack Dempsey is the heavyweight champion of the world!”

“No, he ain’t either,” the newspaperman returned laconically. “They don’t reverse those decisions. If you had a kick to make, you should have pulled Jack out of the ring when it all happened. It’s too late now.”

“Not with the real fans who know the racket, it ain’t,” my overenthusiastic second insisted. “With them, Jack Dempsey is the heavyweight champion of the world. It’ll never be any other way.”

The newspapermen looked at me.

“What do you say about it, Jack?” they demanded.

I shrugged. “I’ve got nothing to say, boys. You saw what went on in there and you’re damned sight better judges than I am. I was too busy trying to fight. But don’t get this handler wrong. It’s his loyalty as much as his judgment that speaks.”

Suddenly a piping, unimportant voice rose from near at hand. I glanced up, and it was the fellow in the little brown suit with the shabby felt hat and the fuming cigarette.

“What the hell!” he exclaimed stridently. “What if he is champ, or what if he ain’t? He’s young, ain’t he? He’s got dough, ain’t he? He’s famous, ain’t he? I ask you, what the hell’s the champeenship of the world to a guy like that?”

So, from the great mass whose gift to me was fame and fortune, came finally a philosophical gem in the shape of unintentional advice. This little chap was right. I had my share of the fame and the fortune. I had lived down the things that once were held against me. I had been champion of the world, and I had been a fairly good one.

Suddenly the sun-washed shores of California looked awfully good to Jack Dempsey. I urged my handlers to hurry with their tasks that I might the sooner get to a telephone and talk with my wife. I thought again of what good old Bill Brennan had said when defeat overtook him in the person of myself. “That’s the fight racket.” Two cannot win a fight, and I’d had more than my just share of victories.

I looked again at the anemic little man in the brown suit. His sharp little eyes peered right straight back at me. While the others worked on me, I grinned again and winked at him. Whether he knew it or not, there was a world of appreciation in that final gesture.

For Dempsey’s full account, including his views of his first loss to Tunney in 1926, read “In This Corner” in full here.

In This Corner

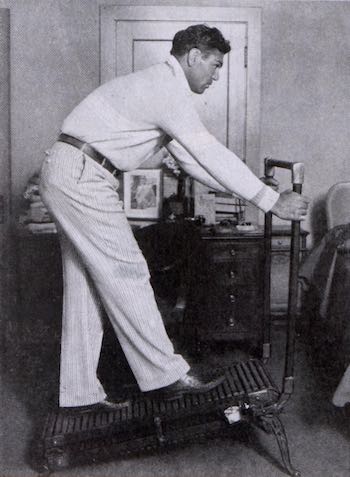

on a treadmill in his room .

Originally published August 29, 1931

Announcement of my match with Gene Tunney brought an immediate offer from a real-estate concern in Hendersonville, North Carolina. They were willing to pay me $1,000 a day for 30 days if I would train there. At first flash this struck me as an economical method of getting in my training for Tunney. I had just so much training to do anyway, and the idea of collecting $1,000 a day for it impressed me as essentially desirable. Accordingly, I went to Hendersonville.

In June preceding the Tunney fight, I underwent this change of climate and water. It had a very bad effect upon me. I contracted chills and fever, to which I always have been subject, and following that, had a series of boils which lasted virtually up to the time of the bout. Please do not understand this as an alibi for my loss of the title. If I had only my own story to tell here, I would make no mention of this condition. I do it, however, to spike the absolutely false rumors that I was drugged in my first contest with Gene.

Nothing was farther from the truth, and I welcome this opportunity to say so. Anything that will relieve my trainers and associates of the reflection such rumors cast upon them is a welcome thing to me. It is perfectly true that I was nothing like the old Dempsey that first time in the ring with Tunney. My trainers, however, cannot be blamed for this. I had been a sick man for weeks, and, had they not been great trainers, I never even could have stayed in the ring with Gene.

Beaten before Entering the Ring

There comes a time in the life of every athlete when that vital spark of youth dims in the shadows of advancing years. While I was training for the first Tunney fight, it came to me often that age had cast its shadow across my path. I did not believe that I was too old to fight, but I did know that I was quite unable to do road work as of old. When I was in the ring I was sluggish. Unable to shake off this apprehension, I became obsessed by it. I knew that I looked bad in the ring and I knew that I felt bad out of it. In the privacy of my own room, I used to ask myself if the final bell had rung for Jack Dempsey. I simply could not believe this and attributed my condition to my illness.

In the light of later events I realize now that Hendersonville itself had nothing to do with the illness which overtook me. It is a delightful place and I was among delightful people. There were, however, changes of water and climate which may have paved the way for the illness which overtook me.

But I must not get ahead of my story. So many things happened before I actually boxed Gene that I cannot in justice omit them from this narrative. First, I went to a place just outside Saratoga, New York, to train for the fight. Then I began to realize what Tex Rickard had meant when he told me not to pay any attention to propaganda in the East. From some source there developed a great furor against the Dempsey-Tunney fight. Many perfectly sincere people who had been misadvised about my attitude toward boxing Harry Wills claimed that we were making discriminations against the best of the contenders. No one seemed to give Gene Tunney much of a chance to defeat me, whereas many said that the Black Panther might turn the trick.

The New York State Boxing Commission more or less, apparently, shared this viewpoint, and Tex discovered that he would have great difficulty promoting my contest with Tunney in the state of New York. Naturally both Gene and I wanted it held in New York State, because we felt that the gate would be bigger there than anywhere else. Tex, however, never was caught without an ace up his sleeve. While his enemies sought to harass him in this big promotion, he calmly made arrangements to move the fight to Philadelphia and the Sesquicentennial Exposition. In this he really outguessed everybody.

While I was at Saratoga, Doc Kearns opened his now-famous legal fight against me. This he predicated on the contracts he had signed with Rickard in Chicago. The first I knew of it, he attached all the money I had in New York banks.

When it was decided that the fight would take place in Philadelphia, Rickard shifted my training camp to Atlantic City. Doc and his array of legal talent followed me so completely and so efficiently that every time I hit a punching bag I expected to see a summons drop out of it.

Actually I got to a point where I forgot all about Gene Tunney and the coming fight with him. I was involved in one of the hardest battles I ever had in fighting Jack Kearns. It seemed to me that I spent every day in court instead of in the training ring. Nervous strain, coupled with my weakened condition, led to a case of intestinal influenza which clung with the tenacity of a bulldog. To top this one, a sparring partner innocently presented me with a robust case of barber’s itch. The ensuing skin eruption gave sustenance to the rumor that I had been poisoned.

Finally, in desperation, I went to Tex Rickard with the hope of getting a postponement of the Tunney contest. I told Tex the flat truth. I was in no condition to fight and I could not get into condition. This was so obvious that even my training staff knew it. Under the circumstances, I am confident we would have postponed the fight, had it not been for the men from South Bend, Indiana, who were endeavoring to get an injunction to prevent the Dempsey-Tunney fight, on the score that they held a previous contract with me to fight Wills. Tex was just about as worried and upset as I was. It would have been folly to increase our woes by postponement of the fight.

Trying to Keep Dempsey Money for Dempsey

Again, Tex was terribly upset in his efforts to protect my money, as he had promised me at Fort Worth he would do. Every scheme we got for the protection of the funds seemed to us full of holes. We dared not put it in a local bank because of the fear that Kearns would find and attach it. Neither dared we wire the money to California, for exactly the same reason. To think of carrying such an enormous sum about the training camp impressed us as sheer idiocy because of the open invitation to gangsters and the dire results their appearance might provoke. Ultimately we schemed to wire the money to a bank in St. Louis, and so our plans remained set until, by the merest chance, we discovered that our enemies knew all about it and would attach the money the instant it landed in St. Louis.

Under my contract, I was not to receive any payment until after a satisfactory fight. Tex could not, therefore, pay me until the fight was over. What we finally did was to wire the money to Los Angeles, where my brother Joe was waiting for it. Something more than $800,000 was credited my account out there, with instructions to the bank not to release the money until they had Rickard’s telegraphic okeh to do so. Just between us, that’s the way I managed to get my payment for the first Tunney contest. Just as soon as the bank opened the morning after the fight, my brother Joe was there and the bank handed him a certified check.

I never had the faintest idea of winning that first contest with Gene Tunney, once I had got well enough into my training to know that I could not get into condition.

In this frame of mind, I answered the first bell there at Philadelphia. I went after Gene just like I went after Firpo, and very much the same thing happened, though Gene did not hit me as hard as Luis. I hooked a left, Gene side-stepped and crossed a beautiful right straight to my chin. The punch dazed me. That told me the story before the crowd sensed it. I remember thinking that either I was worse than I feared or Gene was a lot better than I thought. During that contest I was so bad that my seconds got to fighting among themselves in my corner. Each had a plan all his own, and I certainly could not fight three different fights.

Joining the Ranks of Ex-Champs

People do not realize what a beautiful exhibition of boxing Gene Tunney gave that dismal night in Philadelphia. He was master of every trick. His footwork was superb, his thinking perfect and he punched with the precision of a watch. I was licked and I knew I was licked.

After two or three rounds, I was fighting with one thought in mind only. That was to prevent a knockout. I wanted to go the limit and maybe get Gene some other time when I felt I could give him a better fight. Only one thing saved me in this. I discovered that Gene could counter beautifully, but either he would not or could not lead. This saved me.

I made my own fight, so lasting the limit. The rain bothered us both. I could not see and I had no doubt this slowed Gene up just as much. Had Gene but realized it, I was a ripe subject for a knockout punch had he forced the fighting. No doubt he was fighting with extreme care because he knew as well as I did that he could not lose the decision on points. He was too good a boxer for that. He fought wisely, but he fought carefully, and I was tremendously glad of it. I knew that night that I had no chance whatsoever to beat Gene Tunney. I knew that he was certain to defeat me. All I hoped for, all that I wanted and all that I achieved, was to avoid a knockout at his hands.

I have said before in this story that temperamentally I either tread the peaks or wallow in the depths. It seems to me, as I look back, that events always did exactly the same thing around me. It was a crushing thing for me to stand in that wet ring in Philadelphia and see the hand of Gene Tunney raised in token, not alone of his victory over me but of the heavyweight championship of the world.

It seemed to me at that moment that the heavyweight championship was mine — something which no one could take from me. In a hazy sense I realized that it was gone, yet I felt no different myself. There was a great void, suddenly, but my conception of it was limited.

Previous to the fight, I had contemplated the probability of losing the title and this, I think, carried me over that sad moment there in the ring at Philadelphia. My seconds were simply overcome. They could not grasp that Jack Dempsey, the invincible, had suddenly become vincible. I was beaten fairly and squarely and completely by Gene Tunney. A new heavyweight king had been crowned. Jack Dempsey became but a shadow cast against the wall along with Willard, Jack Johnson, Bob Fitzsimmons, Jim Jeffries, and those other names which forever shall ring down the corridor of pugilistic history.

Right then, when I was wallowing in the depths, events also wallowed with me. On the way out of the ring, there was considerable scrambling to get near me. In this rush of the spectators some woman was knocked down and trampled. She immediately brought suit against me for $50,000, claiming that I had struck her! That is an indication.

Tunney’s sharp, stinging right hand cut my eye somewhat and bothered my ear. I was sore and weak after the contest. Besides this, I felt no particular ill effects other than the loss of my heavyweight championship. Had I been a well man going into that ring, I am convinced that I would have tossed aside the boxing gloves forever, following my defeat. However, my illness convinced me that old age had not robbed me of the zip of days gone by. I had a lingering suspicion that if my condition had been right, I would have been the Dempsey of old. Because of this suspicion, I longed for a second chance at Gene.

Here I want to correct an error I made earlier in my story. I stated that following the loss of my championship to Gene at Philadelphia, I called upon him. This was in error. Gene called upon me. It was a gracious gesture on his part, and one I shall always appreciate. Then it was that he heard from me some advice which I think Gene will admit was good. As I spoke to him, I knew a sort of aching sense of loss because I no longer was champion, and an amazing sense of relief because of the very same fact. No more great lawsuits, no more summonses, no more arguments and legal affrays the substance of which, frankly, always was doubtful to me and the legal jargon of which left me in a state of confusion and disgust.

Estelle was on her way East and learned of my defeat en route. She came to me in Philadelphia.

“What happened, honey?” she asked.

“I forgot to duck, babe,” I answered.

That was all that was ever said between us about my defeat. We two spent a few days resting in Atlantic City, then went to New York for a day or two. Following a brief sojourn in the metropolis of the world, we returned to California. All this time there was that hankering wonderment in the back of my mind as to whether or not I really was washed up as a fighter.

Two or three months of rest out on the Pacific Coast may have softened me up physically, but they rested me mentally, and I overcame the effects of the influenza and boils. During this time I had ample opportunity to think things out for myself, and in my own way. As the ravages of illness disappeared, I began to feel something which might have been the old pep coming back into my muscles and bones. Let me say that I thoroughly enjoyed that period of inactivity so long as I needed it physically. Just as soon, however, as something of my old strength returned, the itching of my insteps once more asserted itself. I had to have action of some kind. Further, I had to satisfy that hankering wonderment in the back of my mind. Was I really washed up, or did I lose the championship because I had a tough break in meeting a great fighter when I was not in condition for the test? What possible answer was there to that question but another try at the good old game?

The Chance of a Comeback

Of course, I kept in touch with developments in the ring. I watched carefully the Sharkey-Wills fight and again the Sharkey-Maloney contest. I saw that Jack Sharkey was rapidly climbing to the top of the heavyweight division. I knew that he was a good, fast fighter, and his knockout victories over both Wills and Maloney marked him a dangerous contender.

In the meantime, Tex Rickard had got in touch with me and was beginning to suggest a comeback with some very good heavyweight. He intimated that if I could scale the barrier of a really good contender, I could step in again with Gene Tunney. Tex always maintained to me that I could beat Tunney. Probably, because he was a great promoter, he maintained to Gene that Gene could beat me. In any case, he would telephone me in Hollywood and keep the idea of another fight fermenting in my mind. He would constantly recall our talk in Philadelphia before I lost the championship.

“You know you were in no condition that night, Jack,” Tex would say. “You know we would have postponed the contest if it hadn’t been for those other things.”

Tex knew his onions. I was a fighter who simply could not resist the call of the ring. Added to this, I was a fighter who had lost the championship under conditions which, right or wrong, he believed to have been against him. Tex counted upon these things and kept after me with them, but I was sensible enough to want to be certain that my condition warranted another Tunney battle.

Without much ado, I went away to the ranch of a friend. There I buckled into the arduous business of chopping trees to see if I could round myself into shape. After a brief time down there, I became convinced that I could get back into condition. I wired Tex Rickard that I would accept a proposition to box Jack Sharkey. Tex immediately made me the proposition and I came East to train.

Once again I established myself near Saratoga. Tex Rickard had the vision of a second Dempsey-Tunney contest, and I was certain that he felt I could beat Jack Sharkey and Gene both. He more or less proved this when he came to me at the training camp and suggested that I have Leo P. Flynn as my adviser.

“You were in no condition at Philadelphia, Jack,” Tex told me. “You were worse than you had any right to be, well or sick. This time you can train without too much to distract you, and I want you to train right. Flynn is interested in this thing and he knows more about boxing than any man I can remember. Put yourself in his hands, Jack. Shoot the works on his judgment.”

I accepted that proposition just as it was submitted, and Leo P. Flynn took charge of my training. From the moment we began, he insisted that there was but one way to fight Jack Sharkey. That was to go out and punch, punch, punch until one of us dropped. Flynn had a theory that Jack could not take punishment to the body. He knew that Jack was fast as lightning and a good boxer. He knew that he was a great deal younger than I. We both knew that my legs were not what they once were, and I would have to be careful not to let Sharkey move me around the ring too much. But he had his theory and we staked everything on it.

I bet everything on the Flynn advice throughout the period of training and in the contest itself. We need not spend too much time, I think, in going over that contest with Jack Sharkey. It is too fresh in the minds of the fans. Jack certainly out-stepped me for the first five rounds. He peppered me with a good many punches, and at times, I must confess, had me wondering if someone weren’t throwing rocks at me from the gallery.

But he paid for it all by giving me shot after shot at his midsection. Throughout the battle I was content to let him pepper my head with his lefts and his rights, so long as I got my lefts and rights to his body. I presume, owing to the type of battle I offered, that Jack was way ahead on points at the close of the fifth round. But I was confident that if I could keep going long enough, I would drop him with those body blows.

Sharkey’s Costly Negligence

In the sixth round, I got to him pretty solidly to the body and I knew that he was feeling the punishment more than he wanted people to realize. That gave me a lot of encouragement. I went back to my corner at the end of the sixth and told Leo Flynn that I was going to knock Sharkey out.

“Just keep punching, Jack,” was all Leo would say to me. “Keep punching, big boy. He’ll fold up.”

At the start of the seventh round, I went methodically back at my job. No matter what happened, I would whale away at Sharkey’s midsection. Sometime during the earlier part of the round, he stepped back and claimed that I was hitting low. To the best of my knowledge and belief, I was not. But I will say this, I was hitting, and hitting hard. All I thought of while I was in there was to flay Mr. Sharkey’s body. Shortly after the first complaint, he turned to make another to the referee.

Perhaps I “copped a sneak” on Jack, but I certainly violated no rule of the prize ring. My feeling is that when a man reaches the point where he classes himself as a contender for the heavyweight championship, he must have the mental control, the poise, and the good sense to conduct himself in accordance with the rules. The rule states that out of a clinch he must defend himself at all times. As Sharkey turned away from me, I lifted a left hook from the body to the chin, and that was that. Mr. Sharkey went down and did not get up.

I knew during that Sharkey fight that I had not entirely come back to the condition I had enjoyed as champion. The old, hankering wonderment came to me again. I was a whole lot better against Sharkey than I had been against Gene Tunney at Philadelphia, but was I as good as I ever had been? Were those shadows which come suddenly out of the future and make of the present, the past, so to speak, really engulfing me? Was I getting old? Was I all through? Was the name Jack Dempsey to slip quietly but certainly into the archives rather than into the headlines?

A Chance to Regain Lost Laurels

I will admit that I was not sure.

Following my knockout victory over Jack Sharkey, Tex Rickard immediately propositioned me for another match with Gene Tunney.

“The old iron is hot again, Jack,” Tex said to me. “Now is the time to strike. This win over Jack Sharkey puts you right out front with Tunney himself. You laughed at me a few years ago when I told you that we would draw $1,000,000 with the Carpentier fight. Laugh at me now, if you dare, when I tell you we’ll draw at least $2,500,000 with you and Gene in the ring again.”

Who can know but that man who has lived through the experience, what it means to wonder whether you are good or bad? I had every reason to feel I had been a great fighter. I hadn’t as yet had incontrovertible evidence that my day was gone. The old fighting heart and the old fighting instinct throbbed within me for expression. I hated the thought of anybody else in possession of my heavyweight championship. I reasoned the thing out very carefully in my own way; thought it out when I was alone at night with none to bother me.

There was one thing which seemed certain to me. That was that I would knock out any man I hit right. What if my legs had slowed up a trifle? What if the old zip and speed were gone from my bobbing and weaving? These things must essentially be offset by experience and by knowledge. I felt strong as an ox, and because most of my contests had been short, I had never really taken any serious beatings. Why, then, should I not gamble that at least once in 10 long rounds, I could tap Gene Tunney on the chin, or under the heart, with a punch that would win me back the heavyweight championship of the world? There was no good reason to suppose such a thing unreasonable. I felt that I could hit Gene; felt that I could plan out a campaign of battle that sooner or later would bring him to me for that one lovely punch.

With this in mind, I considered the possibility of a $3,000,000 box office. Aside from the money that would establish Tunney and myself as the greatest financial figures boxing had ever produced, I was a comparatively rich young man when these problems presented themselves. I could have retired then as easily as I retired later, and lived on my income.

So it was not entirely money by which I was actuated. There was — and I do not say it sentimentally — an appreciation and a love for the sport of boxing which superseded in my calculations every financial angle. I think, perhaps, I was a big kid who had lost a toy and wanted to fight to get it back again. In any event, I told Tex Rickard to match us, and I promised myself that I would give Gene Tunney a whole lot better fight than I had given him that rainy night in Philadelphia.

My contest with Jack Sharkey netted me almost $500,000 and, to put it in the jargon, I was sitting pretty, financially. There was nothing between me and retirement other than a determination on my part to satisfy that hankering wonderment as to my own condition. I knew perfectly well that I wasn’t 30 percent of the old Jack Dempsey the night I lost my heavyweight championship. On the other hand, I knew perfectly well that Gene Tunney was a fine fighter and a whole lot better than the public has ever given him credit for being. There lay the problem.

I knew that my win over Sharkey indicated that I was in fair physical condition. I felt that a good training siege would put me back in excellent condition. Furthermore, I was perfectly certain that when I was in condition, the man did not live who could box me 10 rounds without at some time or other being hit on a vital spot. I knew perfectly well, as I have said, that anyone I hit on a vital spot was very apt to be counted out. That was my bet on the Tunney fight at Chicago. I believed that the worst I had was a 50-50 chance to regain the championship, and that is exactly the right percentage for a great fight.

I went to Chicago to train. Leo Flynn once again took charge of my training and acted in the capacity of chief adviser. I think that most of the fellows who realized my condition before the first Tunney contest favored me to win over Tunney in the second. There were all sorts of rumors floating about my camp to the effect that the gamblers had everything set against me once again. This time I did not easily fall for those rumors.

No Fixers Wanted

I had been knocking around the $1,000,000 gates long enough to know that a good many shady things were attempted. But I also had seen enough of Gene Tunney to know that it was not in his mind or his heart to fake a championship prizefight. This absolute confidence in Gene gave me the greatest weapon I had to use against the fixers who later approached me.

It is not easy to sit here and write these details. I feel that I must do it, however, in justice to myself and in justice to Gene Tunney. I have often hoped, to be truthful about it, that Gene would write his life experiences. I certainly would like to read them and get the other side of our two contests. In my own relation of events, I have stated the absolute and simple truth just as closely as I know how. I know that Gene would do the same thing. Out of a contrast of the two stories a pretty situation ought to develop.

I positively was approached by people in Chicago. I was, in fact, told that for $100,000, I could win the heavyweight championship. I laughed in their faces for a good many reasons, the principal ones of which I am going to relate. They are so obvious and so indisputable that none can deny them.

First, I refused because I had planned a careful campaign against Gene Tunney and believed that I could beat him on the level. Second, I never would trust anybody who would take or give a bribe. Third, I have never faked a fight in my life and I never will. Fourth, even if I did lose my head and pay such a craven bribe, I knew nobody could fix Gene Tunney, and Gene Tunney was the man I had to fight. Next, despite the advice of some people who harassed Leo Flynn and myself, I felt that my coming contest with Gene was the last I ever would fight, win, lose, or draw.

If I won, I planned to retire undefeated. If I lost, nothing more need be said. So I laughed in their faces when they made me this proposition.

The fight itself has hardly wilted sufficiently in the public memory to warrant a detailed description here. I went into the ring planning to work on Gene much after the fashion I had worked on Jack Sharkey in my last contest. In Tunney, however, I was fighting a better fighter than Sharkey. I do not wish to be unkind in that statement; I merely state the fact.

Down for the Long Count

No matter what happened, Gene remained as calm as a mill pond. At times, his machine-like perfection was maddening to me. That darting, straight left jab of his, coupled with an inside, straight right cross that had great jarring possibilities, sufficed to fill anybody’s evening with bouquets that were loaded with reverse English. Gene could fade away from an attack and at the same time hook a jarring left to the liver as well as any fighter who ever lived. So I did not fight him exactly as I had Sharkey. I took more precautions. I felt from my first experience with Tunney that he would draw the lead from me and counter. I planned my campaign entirely on that supposition. It worked out perfectly.

Just as I had planned, I finally got my shot at him. The rest is history. The fact that it is disputed history is of no vital importance at this moment. I have stated previously in my story what Tex Rickard said to me on the afternoon I boxed Georges Carpentier. He told me that I was the sort of a kid to whom things happened.

There are people like that, and I am confident that I am one of them. Even in my present activities, events can run along at a fight club in the even tenor of their way, show after show after show. But let me appear in the capacity of referee and the unusual happens. This has recently been true twice in Madison Square Garden at New York City. It was true the other night in Los Angeles. It seems to me to be true wherever I go. It certainly was true that night in the Chicago Stadium when I caught Gene Tunney in a corner of the ring and knocked him down for the historic “long count.”

If anyone thinks that I am here to express any opinion as to the merit of that “long count,” they have another think coming. All I have to say about that hectic contest is that I fought the best that I knew how to fight. I put into that battle everything that I could summon in the lexicon of physical equipment and experience. When I cornered Gene and knocked him down, I felt the exultance that came to me that July Fourth in Toledo when I won the championship from Jess Willard. Gene was down, and, boys, he had been hit! A look at the motion pictures of the battle will indicate just how many punches Gene absorbed as he toppled over there against the ropes.

I want to say something else in terminating my story. Gene Tunney, on the floor of that Chicago ring, showed the world more of the stuff of which a champion is made than he did in the entire fight at Philadelphia. I don’t think Gene even knows how to spell quit, and I don’t think he’ll ever learn how to spell it. He has the equipment and the heart of a champion. Had he not, he never would have got up off that ring floor in Chicago inside a hundred count.

All the way through that contest, I figured it a hard-fought and close one. After Gene had got up, following that knockdown, he gave a great exhibition of thinking under fire. I could not catch him for the rest of the round to land a finishing punch. But I kept right on trying in the next round, and as a result of my over-anxiety, Gene dropped me to my knees for a count of one.

It was a red-hot fight, and I don’t think anybody could criticize the performance of either of the contestants. Gene won the decision and remained heavyweight champion of the world. To say that I was not disappointed would be to tell a lie. I was disappointed. But once again I had collected a modest fortune for my efforts, and there was a good deal in my life to console me for the missing heavyweight championship.

After the Fight

There was a home and a wife in Hollywood. There was plenty of money in the bank to take care of me and the family I had caused so much worry in my younger days. There was the Firpo fight, the Carpentier fight, the Fulton fight, and several others which had marked the very peak of thrills for the boxing public. Of none of these need I ever be ashamed. After all, that man who wins a championship should be content. He should not expect to hold it over the hurdles of the onrushing years.

In my dressing room after the second Tunney contest, I was momentarily dejected. As is always the case with dressing rooms, a great many people I did not know managed to crowd in. I presume this is curiosity on their part, and it may be morbid curiosity. A fighter, in defeat or victory, is much like a monkey in a zoo to those who can get close to him. They want to look at your eyes and your ears to see how badly you may have been injured. They want to pick up a word here or a gesture there which, later on, they can relay, magnified, to their own little public.

I have always regarded these curious fans in a tolerant, even friendly way. They are, I presume, out of the great masses which support professional boxing. But I never had come to regard them seriously, nor did I ever expect to receive from one of them a perfect gem of philosophy. But I did.

It came from an emaciated chap weighing not more than a 130 pounds, in high boots and an overcoat. I never will forget him. He had a hooked nose and sharp little eyes that winked incessantly under thin, scraggly eyebrows. He was smoking a cigarette when first I saw him, puffing a cigarette and looking intently at me.

I sat down on the edge of a rubbing table, and my handlers began removing the bandages from my fists. The little chap wore a brown suit and shifted uneasily from foot to foot. He smoked jerkily at his cigarette, inhaling nervously and blowing the smoke upward so that it curled under the brim of a shabby, brown felt hat.

What’s a Championship?

I noticed, for no particular reason, that his finger nails were in deepest mourning about their tips. I grinned at him and winked. He took the gesture as a personal salutation which seemed, from his expression, to illuminate his life.

“Okeh, Jack,” he called to me.

I grinned and winked again. Newspapermen crowded about, but they did not get between us. The little stranger saw to that. One of the newspapermen said:

“Jack, do you realize that Tunney was down for 17 seconds?”

“No,” I said. “I don’t know how long he was down.”

“Why didn’t you go to a neutral corner?” the newspaperman demanded.

“I meant to,” I admitted, “but there didn’t seem to be any hurry about it. The count had started and I thought it would continue.”

One of my seconds growled: “He’s still champion of the world, ain’t he? How many times do you have to count a guy out to win? Seventeen seconds!”

Some other newspaperman spoke up, “It was only 14 seconds,” he said.

“Well,” my handler growled, “up till tonight, 10 seconds has always made a champion! I’m tellin’ you guys right now that, with the great majority of American boxin’ fans an’ with everybody who knows anythin’ about the prize ring, Gene Tunney got a decision tonight, but Jack Dempsey is the heavyweight champion of the world!”

“No, he ain’t either,” the newspaperman returned laconically. “ They don’t reverse those decisions. If you had a kick to make, you should have pulled Jack out of the ring when it all happened. It’s too late now.”

“Not with the real fans who know the racket, it ain’t,” my overenthusiastic second insisted. “With them, Jack Dempsey is the heavyweight champion of the world. It’ll never be any other way.”

The newspapermen looked at me.

“What do you say about it, Jack?” they demanded.

I shrugged. “I’ve got nothing to say, boys. You saw what went on in there and you’re damned sight better judges than I am. I was too busy trying to fight. But don’t get this handler wrong. It’s his loyalty as much as his judgment that speaks.”

Suddenly a piping, unimportant voice rose from near at hand. I glanced up, and it was the fellow in the little brown suit with the shabby felt hat and the fuming cigarette.

“What the hell!” he exclaimed stridently. “What if he is champ, or what if he ain’t? He’s young, ain’t he? He’s got dough, ain’t he? He’s famous, ain’t he? I ask you, what the hell’s the champeenship of the world to a guy like that?”

So, from the great mass whose gift to me was fame and fortune, came finally a philosophical gem in the shape of unintentional advice. This little chap was right. I had my share of the fame and the fortune. I had lived down the things that once were held against me. I had been champion of the world, and I had been a fairly good one.

Suddenly the sun-washed shores of California looked awfully good to Jack Dempsey. I urged my handlers to hurry with their tasks that I might the sooner get to a telephone and talk with my wife. I thought again of what good old Bill Brennan had said when defeat overtook him in the person of myself. “That’s the fight racket.” Two cannot win a fight, and I’d had more than my just share of victories.

I looked again at the anemic little man in the brown suit. His sharp little eyes peered right straight back at me. While the others worked on me, I grinned again and winked at him. Whether he knew it or not, there was a world of appreciation in that final gesture.

Bell!

Concluding notes by Charles Francis Coe:

So passeth a champion into retirement?

Jack Dempsey is in retirement just about as much as Mussolini. In the course of my own peregrinations I come in contact with a great many well-known people, but I have yet to meet a man whose personality so exactly befits the throngs as that of Jack Dempsey. I have, too, yet to meet a man for whom the throngs have such frank and outspoken admiration.

In order that I might gather firsthand the atmosphere which surrounds this boy in his present vocation, I barnstormed with him from coast to coast. I say without equivocation that he is the greatest and best influence in American boxing today. Many things have conspired to this end, but primarily it is Jack himself and his fondness for the profession which has meant so much to him.

A Sad Blow to Boxing

The retirement of Gene Tunney from professional boxing and his severance with all things having to do therewith was a sad blow to boxing. The continued presence of Jack Dempsey as an active force in the sport more or less offsets that. Wherever he referees, it is a safe gamble that the paid admissions double. I would not make that statement unless I was absolutely certain of my ground.

“It’s the old game itself, Sacker, that counts most,” Dempsey has said to me repeatedly. “All the bouts can’t be held in New York City, Chicago, or Los Angeles. There are little towns, too, and they have just as much right as the big ones. So I play them all.”

In Pottsville, Pennsylvania, an ordinary-run boxing show turned away hundreds the night that Jack Dempsey was there to referee. The very next night in Scranton, Pennsylvania, the huge armory there was jammed to capacity and in the main bout there had been a substitution. Ordinarily this would detract from the box-office receipts. Your prizefight fan is a discerning individual who knows records and keeps himself pretty well posted on what he wants to see. Substitutions at the last minute are fatal. This was not the case in Scranton. The armory was jammed. Dempsey was there!

Everywhere we went that day, throngs greeted us. I know that the ex-champion signed his name at least a thousand times. I know that the office of Mayor Fred K. Derby was jammed to capacity to greet him. I know that when Fred Derby was introduced in the ring that evening and, in turn, introduced your correspondent, I looked out upon a perfect sea of faces which were interested only in one thing — that was to meet and hear from Jack Dempsey.

I know that the home of E.J. Coleman in the exclusive residential section of the city looked like a veritable circus ground when it became known that Jack and I were guests there. I know that every boxer who appears on a fight bill when Dempsey is present finds it second nature to give to the last ounce of his energy and ability. Jack carries everything along. His energetic, pleasing personality, his understanding and tolerance of the endless throng, and his reputation make him absolute public property.

He Must Have His Little joke

In the telling of his own tale, he naturally has disclosed a good deal of his personality. The courage he showed throughout his ring career and his utter disregard of early discouragements speak for themselves. But there is another side to the lad which may not have been driven home. That is his absolutely boyish love of fun.

In Scranton, on the night to which I have referred, he was presented in the ring with a pen-and-ink sketch of himself by a noted local artist. In order that this event might be achieved with due pomp and ceremony, many illustrious persons were in attendance. During the preliminary bouts Jack and I sat together at the edge of the ring. He was the cynosure of thousands and thousands of eyes. Seated on his left on a raised platform was one of the judges who rendered decisions on the bouts. On the left of the judge sat Mayor Fred K. Derby. All this had little or no effect upon Jack.

I casually looked about to say something to him, and found him on his hands and knees, crawling under the edge of the ring. In something of amazement, I followed his movements and discovered that he was assiduously employed in sticking a paper match between the sole and the upper of Mayor Derby’s left shoe. Having arranged this to his satisfaction, I saw him ignite the match, then drawback to sit giggling beside me while watching the mayor’s face in gleeful anticipation.

When the authority of the match asserted itself in the life of his honor, Jack’s face was the absolute picture of innocence, and he appeared to be deeply engrossed in a conversation with me. The mayor glanced in our direction suspiciously, leaned around behind the back of the judge’s chair, and winked smilingly at me.

I said to Dempsey: “At least 2,000 people saw you do that to the mayor, Jack. Suppose he had failed to see the joke?”

“He wouldn’t,” Dempsey answered tersely.

“Some day,” I said, “you’ll pick the wrong one.”

“A bird who can’t see a joke on himself,” he laughed, “will never be big enough to bother you. Anyhow, I’ll take that chance. Smart folks, Socker, just keep smilin’ along. What would we all come to if we couldn’t laugh?”