10 History Facts You’re Probably Getting Wrong

“It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble,” Mark Twain once wrote. “It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.”

To help you avoid a little trouble in the future, we present a handful of historical myths that are commonly believed, but “just ain’t so.”

1. “Caesarean Section” got its name from Julius Caesar, who was born by this method of delivery.

No records indicate Caesar was born by C-section. In fact, doctors in ancient Rome only performed this procedure on mothers who were dead or dying, and Caesar’s mother was reported to still be alive when Caesar was in his 40s. The word “caesarean” is probably an alteration of older Latin words for “cut” or “postmortem birth.”

2. Nineteen women accused of witchcraft in Salem, Massachusetts, were burned at the stake.

No “witches” were burned at the trials, which took place between February 1692 and May 1693. All nineteen women were hanged. Although no Massachusetts women were burned at the stake, it is estimated that many European women were. Of the 40,000-50,000 women who were executed for being witches, burning was the preferred method because it was said to be the most painful.

3. All men in the Revolutionary War era wore wigs.

Wigs became popular in the 1600s when an outbreak of sexually transmitted diseases caused many men to lose their hair. By the 1700s, long hair was still stylish, but wigs were on their way out. A historian at Williamsburg estimates that 5% of the population in colonial Virginia wore wigs.

Soldiers kept their hair long, but they powdered it to make it resemble the powdered wigs of the previous century. George Washington’s hair, which you see represented on the quarter and dollar bill, was all his own.

4. On the night of April 18, 1775, Paul Revere rode through the Massachusetts countryside, shouting “the British are coming.”

The purpose of Revere’s ride was to warn the militias in Concord that the British regular troops were on their way to seize weapons and supplies the patriots had stored there. He was also ordered to warn Samuel Adams and John Hancock in Lexington that the British would probably be coming to arrest them. He did not shout “the British are coming” because it would have made no sense. At this point, most colonists still thought of themselves as British. And he wouldn’t have shouted in general because he was trying to avoid arrest by British regulars on the road.

Revere alerted the militia in Medford and Arlington before reaching Lexington and passing on his warning to Adams and Hancock. Revere proceeded to Concord but was caught by the British, questioned, and released. End of ride.

5. There were no survivors from the Alamo.

After overwhelming the men holding the Alamo in 1836, Mexican troops executed 200 of the surviving soldiers. However, 13 wives and children of Texan soldiers were allowed to leave. The Mexicans also released a slave of William Travis and a Hispanic man who fought with the Texans but convinced the Mexican soldiers he had been a captive.

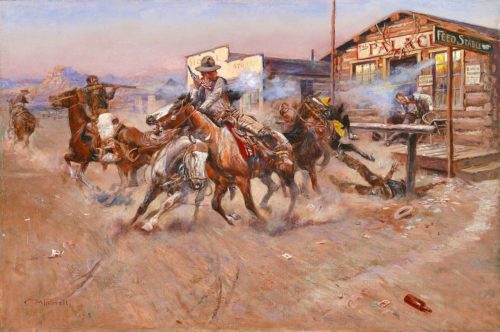

6. The early days of the American West were a time of widespread lawlessness; shootings were common, as were bank robberies.

The truth of this assertion is hotly debated, with both sides citing quite different figures. However, one statistic shows four Kansas cow towns were more peaceable than their reputations. Between 1870 and 1885, the number of gunshot deaths in Wichita, Abilene, Dodge City, and Ellsworth was 45.

The total number of bank robberies in 15 western states between 1859 and 1900 was probably less than 10. By way of comparison, there were over 4,000 in the U.S. in 2016.

7. Thomas Edison invented the light bulb in 1879.

At least two men were ahead of Edison in the light bulb’s development. In 1802, Humphrey Davy created an electric arc lamp, and in 1840, Warren de la Rue produced a light bulb with a platinum filament.

8. After the Wall Street crash of 1929, many stock brokers committed suicide by jumping out of the windows of their offices.

The suicide rate in Manhattan rose only slightly after the crash. Only two men are reported to have jumped from a tall window. (The rate of suicides was actually higher in the summer months before Black Friday.)

9. Charles Lindbergh was the first man to fly nonstop across the Atlantic ocean.

John Alcock and Arthur Brown flew a Vickers Vimy biplane across the Atlantic in 1919. They took off from Newfoundland and landed in Ireland.

10. Every statue of a military hero on horseback tells the fate of the rider. If one hoof is raised, the rider was wounded in battle. Two hooves raised meant the rider died in battle. And a horse with all hooves down indicated a hero who survived all battles.

This rule of — hoof? — is not dependably true. For example, some of the equestrian statues at Gettysburg follow this code, but not all. In Washington D.C., only a third of 30 statues of heroes on horseback comply with this custom.

Featured image: Shutterstock

“Lafayette Is Here”: The Post Covers A Hero’s Return

In the 43 years since he’d helped America win its independence from Great Britain, the Marquis de Lafayette had become a symbol of the revolution. Fighting alongside Washington, he had forced the British army to surrender, then sailed back to France to transplant liberty in European soil.

Early in 1824, President James Monroe invited Lafayette to return to the nation that still revered him, and the Marquis accepted. And so began a thirteen-month tour across all 24 states, covering 6,000 miles of miserable roads, bone-crunching carriages, and sluggish riverboats, one of which nearly drowned him when it sank in the Ohio river.

For older Americans of the revolutionary generation, Lafayette was a living connection to the great cause in their lives. To see the living hero, after all this time, would help bridge the gulf they felt between the early republic and the modern United States.

For younger Americans, Lafayette’s tour was an opportunity to celebrate the success of their nation. They would see for themselves one of the last founding fathers — a representative of all that their nation stood for.

As for Lafayette himself, this tour was one last chance to see his aging comrades-in-arms and to witness the state of the country he had worked so hard to create.

The Saturday Evening Post reported his arrival on August 21, 1824:

The Marquis Lafayette, the only surviving General of the seven years’ war of our revolution, was conducted from Staten-Island on Monday morning, and landed in New York city, amidst every demonstration of joy and admiration could be bestowed. The news of the General’s arrival had spread though the surrounding country with the rapidity of lightning; and from the dawn of day until noon, the roads and ferry boats were thronged with people who were hastening to the city to participate in the fete, and testify their gratitude for the services, and respect for the character, of the illustrious “National Guest.” Our citizens also turned out in immense numbers at an early hour, and, together with the military, presented the most lively and moving spectacle that we have witnessed on any former occasion.

As a young nobleman, Lafayette has been inspired by all the talk of liberty he heard buzzing about in the salons and Masonic lodges of Paris. When the news arrived that Americans had risen up against Great Britain, he leapt at the chance to fight for the rights of man. And, because he was French, to humble Great Britain. And, because he was a young man, win glory on the battlefield.

He stole away to America, expecting to be given an army to command but, upon his arrival, found he would not be given any troops, or even a military rank. At this point, Lafayette proved he was more than just a priviliged adventurer. He volunteered to serve without rank and even donated his own money to the war effort. Impressed by the sincerity and enthusiasm of this young man and fellow Mason, Washington appointed him to his headquarters staff.

Within a month, Lafayette proved the wisdom of Washington’s judgment. At Brandywine Creek, he stepped in to act as a division commander when American soldiers broke and ran from an assault by British and Hessian troops. Though shot through the leg, he remained on his horse to rally the soldiers, mount a rear-guard defense, fight off another British attack, and skillfully withdraw the Americans to safety.

He remained at Washington’s side throughout the bitter Valley Forge Winter, and helped thwart a congressional plan to replace Washington with General Nathanial Greene. He led troops at the battle of Gloucester and was instrumental in the victory at Monmouth. By now, Washington and Congress regarded Lafayette as one of their best generals. Even Lord Cornwallis, commander of the British forces, recognized his importance and launched several attacks on the colonials to capture the Marquis.

In 1779, Lafayette sailed back to France to beg King Louis XVI for more soldiers and boats, then quickly returned to America, where he was given command of his own army. In 1781, the young General drove Cornwallis back across Virginia until he and Washington trapped the British at Yorktown and forced their surrender.

Now, at age 67, he was being showered with honors and crowded by the ecstatic veterans of that long-ago war.

Decidedly the most interesting sight was the [New York] reception of the General by his old companions in arms: Colonel Marinus Willet, now in his eighty-fifth year, General Van Cortland, General Clarkson, and the other worthies whom we have mentioned… He embraced them all affectionately, and Col. Willet again and again. He knew and remembered them all. It was a re-union of a long separated family.

After the ceremony of embracing and congratulations were over, he sat down alongside of Col. Willet, who grew young again and fought all his battles over. “Do you remember,” said he, “at the battle of Monmouth, I was volunteer aid to Gen. Scott ? I saw you in the heat of battle. You were but a boy, but you were a serious and sedate lad. Aye, aye; I remember well. And on the Mohawk, I sent you fifty Indians. And you wrote me, that they set up such a yell that they frightened the British cavalry, and they ran one way and the Indians another.”

No person who witnessed this interview will ever forget it; many an honest tear was shed on the occasion. The young men retired at little distance, while the venerable soldiers were indulging recollections, and were embracing each other again and again… Such sincere, such honest feelings, were never more plainly or truly expressed. The sudden changes of the countenance of the Marquis, plainly evinced the emotions he endeavored to suppress.

When a revolutionary story from the venerable Willet recalled circumstance long passed, the incident… made the Marquis sigh; and his swelling heart was relieved when he burst into tears. The sympathetic feeling extended to all present. The scene was too affecting to be continued. One of the [veterans], anxious to divert the attention of the Marquis, his eyes floating with tears, announced the near approach of the steam ship. The Marquis advanced to the water railing, where he was no sooner perceived by the multitude, than an instantaneous cheer most loudly expressed the delight they experienced.

Through this dense and towering host, (for the doors, casements, railings, windows, chimney and turrets of the buildings were hung with spectators,) the General was conveyed in a barouche and four horses, followed and proceeded by the Lafayette Guards, through the whole distance to the City Hall, which is near a mile.

The General rode uncovered, and received the unceasing shouts and the congratulations of 50,000 freemen, with tears and smiles that bespoke how deeply he felt the pride and glory of the occasion. The ladies, from every tier of windows, waved their white handkerchiefs, and hundreds loosed by their fair owners were seen floating in the air.

Several attempts were made by the people, both in going up and returning through Broadway, to take the horses from the General’s carriage, and draw him in triumph themselves.

This action, which was repeated in other cities, drew a stern disapproval from the Post’s editors.

We regret to see that in New Haven the populace took off the horses and dragged General Lafayette in his carriage. This is not the offering it becomes a free People to bestow upon a friend of Liberty. It is ill suited to the character of Republicans, and only fit for the slaves of some military despot who are willing, both figuratively and literally to wear the yoke. For the honor of the Nation, and, more than all, for the respect due Lafayette, we trust it will not again occur in the progress of such a man through a nation of free men. [Sep 4, 1824]