An Automobile Genius on the Secrets of Innovation

This article and other features about the early automobile can be found in the Post’s Special Collector’s Edition: Automobiles in America!

This year the company for which I work — General Motors — is celebrating its 50th anniversary. For 40 of those years I have been a consulting inventor for the company. We sometimes hear it said that necessity is the mother of invention. If that were true, then it might be said that for the last several decades I have been working my head off because of necessity.

I can’t go along with this maxim altogether. Necessity was certainly not the mother of the airplane. At the time the Wright Brothers were inventing the airplane there was no widespread clamor to fly. People did not believe it was necessary. The Wright Brothers just thought they knew how they could do it and so they went ahead and thereby opened up a huge new field.

It might be argued that it has not been necessary to invent the automobile or to improve it through many inventions in the last 50 years. We would have lived with no more than the horse and the buggy. But I believe we are all thankful for 50 years of improvement in the automobile, and I am sure we will keep trying for more improvement just as hard in the next 50 years.

I am a little afraid of reminiscing. But to measure the possibilities of the next 50 years, it may be worth looking back over the last 50. It is amazing what the invention and development of the automobile and its applications have done to influence the habits and customs of our people in this period. Since 1908, manufacturers in this country have produced 160 million motor vehicles, and today the automobile creates 10 million jobs in highway-transport industries, more than one of every seven existing jobs. It has created a quarter of a million businesses like motels and service stations, and influenced the building of 2 million miles of roads. It has made deep changes in how people travel, how farmers grow and market crops, and where schools are built.

The automobile industry pays about $8 billion a year in taxes. Almost one quarter of the retail price of each vehicle is tax money. This is an enormous burden, yet the automobile industry has produced the greatest transportation system the world has ever seen. One of the most important reasons for this growth has been the industry’s willingness to change its product and its production methods to suit customers’ demands. The industry has been willing every year to design and build new tools which can produce more and better cars.

I do not advocate change for the sake of change, nor do I say that a new thing is necessarily better because it is new or suddenly popular. But if there is one thing the automobile has taught Americans in the last 50 years it is to expect constant improvement in the product. In America we must constantly change and improve or fade away.

Too often people believe that change comes about through the simple process of handing a problem to a research laboratory where an answer is produced mysteriously but promptly. There is no such magic in research. Discovery and invention come only by hard work, disappointments, innumerable failures, and very often the consumption of much time and money. Research is based on patience, skill, and practice and more practice. A theoretical physicist may develop an accurate formula for the curve of a baseball in flight, but it takes a pitcher years of practice to control the curve.

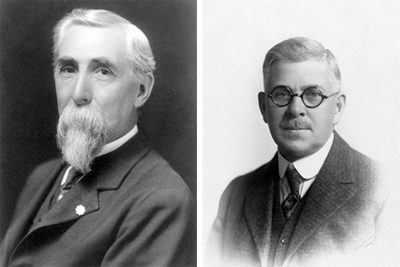

Since its inception the automobile industry has worked and practiced to lift the automobile from the status of a rich man’s toy. It was only a few years before General Motors was born that Ransom Olds discovered one of the secrets of mass production — progressive assembly. And it was just 55 years ago that Henry Leland, who was then head of Cadillac, demonstrated that automobile parts could be made interchangeable. These two developments were basically important to the automobile, but they alone did not make the product a perfect one. Leland understood this very well.

At that time the automobile was cranked by hand, which was not a job for women and usually meant they were relegated to the backseat as passengers. Hand-cranking was not popular with men, either, since there was a constant risk of broken arms. Leland disliked this imperfection and when a dear friend of his died as the result of an accident during hand-cranking, he sent me an invitation to visit Detroit and discuss the problem of making car-starting a safer operation.

This was one time when I might agree that necessity mothered an invention, because in a moment of weakness I told him that I thought a car might be cranked with an electric motor driven from a storage battery. Having made the rash statement it was up to me to produce it, and I worked for months in my small laboratory which was part of a barn in Dayton, Ohio. Eventually we did produce an electric starter, a modification of which became production equipment on the 1912 Cadillac.

This outraged the electrical-equipment engineers. They looked at their formulas and said that it was impossible, that we would need batteries and an electric motor larger than the engine itself and wires five times as heavy as we used. But they were thinking about continuous-running electric equipment. But we were not planning to transmit current 100 miles or work our electric motors 24 hours a day. We wanted a spasm of power, a big torque for a short time, and after the engine was turned over and started, the little starting system could lie back and rest and be recharged for the next start. So we disregarded the power rules and made driving possible for millions of people who couldn’t or did not want to hand-crank an engine.

Ten years later we could manufacture automobiles at the rate of one a minute, but they were not getting to the customer at that rate. It took one or two weeks to paint the car because the system that had been used on carriages was being applied to automobiles. The increased production resulting from the growing demand for closed cars could not possibly be met by using the old finishing methods.

Eventually the answer was found in the chemist’s test tube, although the you-can’t- do-it boys were on our necks all the time telling us we were wrong. Now, instead of several weeks to paint a car, it takes an hour to spray on the required number of coats of quick-drying, durable, colorful lacquer. The bottleneck to customers’ demands was broken.

In this business of ours you never solve one problem without, nine times out of 10, coming face to face with another one. After we had put electric starting, lighting, and ignition on the Cadillac we became sitting ducks for attacks aimed at us by the people whose toes we had stepped on when we electrified the automobile. In those days the quality of gasoline was hit-or-miss and the quality went down as automobile production went up. Engines began to knock all over the place. Naturally our competitors blamed the increasingly prevalent knock on our new ignition system.

In order to defend ourselves it was up to us to find out what really did cause knock. It was a problem that had also arisen with the Delco farm-lighting systems which I had originally devised so that my parents could have light and running water on their Ohio farm. To do this job we put a fellow inventor, Tom Midgley, to work studying this annoying matter of knock which was keeping us from increasing the compression in our engines. Happily neither Tom nor I was an orthodox chemist or thermal engineer, so we were wholesomely ignorant of the obstacles. We had a fine chance to make some informative errors in this field.

In the period before World War I, we had found out first just when knock occurred in the combustion chamber. It was after the ignition spark; and not before, as everyone had supposed. With this knowledge in hand we started a series of experimental treatments of the fuel. I remember that the first one was the introduction of coloring matter based on the heat-retaining characteristics of a certain flowering plant. We got a promising result, only to learn by checking with another substance that color had absolutely nothing to do with it. Nevertheless we learned something from that, and as we went on to test other additives a pattern of behavior began to appear.

The motoring public will never know how lucky it was that we did not stop in the middle of our experiments. The pattern indicated that the compounds of the heavier elements were most effective in squelching knock. We found two or three that were so good we might have been satisfied with their performance if it had not been for one thing — they smelled terrible. They smelled so bad and the odor was so lasting that the men in the laboratory who handled them were on the verge of becoming involuntary hermits. They didn’t dare go to the movies. But with the pattern leading us in the direction of the heavy elements, I suggested that we take a big leap and try the very heavy metal — lead.

The result of that leap was a whole bookful of trouble — and tetraethyl lead antiknock gasoline, which Midgley and his boys worked out and which is now known as Ethyl to everyone. Before we perfected Ethyl for widespread use, we had to develop a method of extracting huge quantities of the element bromine from the ocean. The chemists again told us this was impractical, since there is only one-tenth of a pound of bromine in a ton of sea water. But we found a way, and now we extract 120 million pounds of bromine from the sea annually. If you want to put a value on the result of our long hard search, in which the entire oil industry cooperated, you can do so in three ways. The superior fuel made possible more efficient high-compression engines. It permitted us annually to leave 25 billion gallons of fuel in our underground reserves which otherwise would have been burned. And at retail prices of gasoline the American motorist has been saving $5 to $8 billion a year.

You can see from just these few examples that the automobile industry was teethed on trouble. Complacency has no place in this business. You have to break out of the ruts if you want to survive. The fact that of about 2,500 makes of automobiles that have appeared only a handful are in existence today is a good illustration of what can happen if you design to suit yourself and ignore the wishes of your boss — the customer.

I am a great believer in the “double profit” system. The producer must make a profit to keep in business, but the customers’ profit must be ever so much greater. If you don’t believe some of these modern necessities, comforts, and conveniences have a definite value to you, just try doing without them. Suppose you were suddenly deprived of your car, electric lights, and power, or the telephone, radio, or television. What would you give to have them back?

—“Future Unlimited,”

The Saturday Evening Post, May 17, 1958

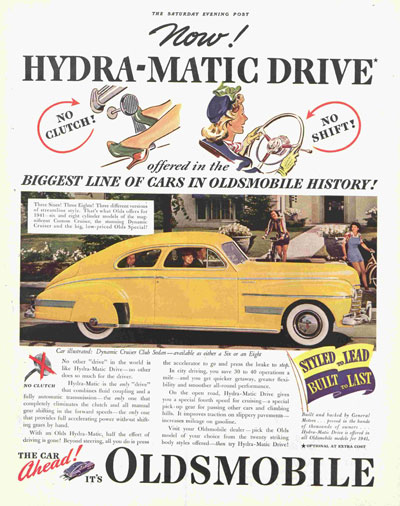

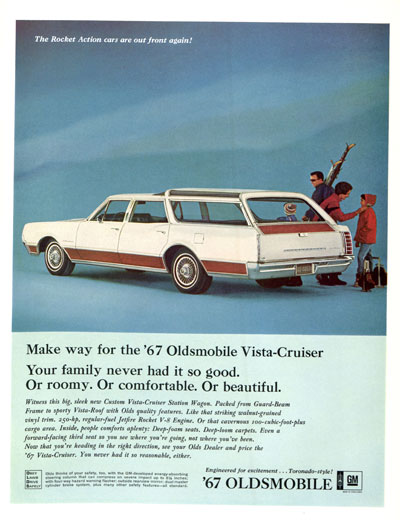

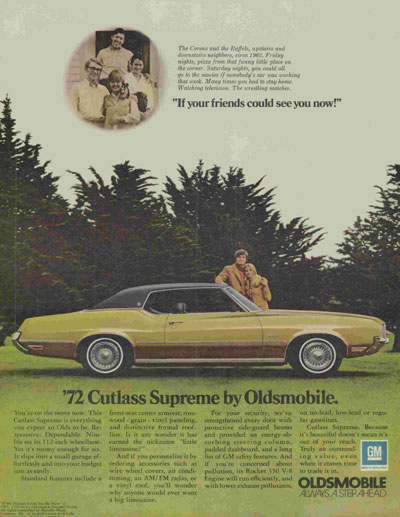

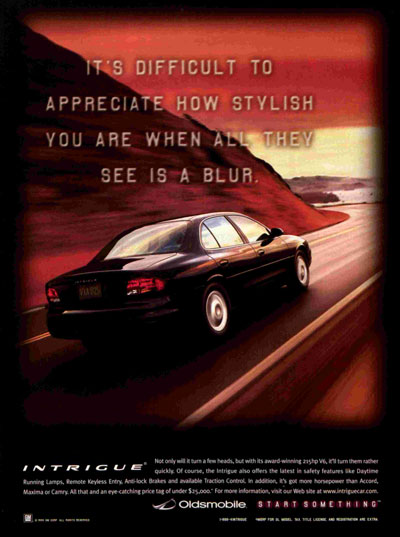

Vintage Auto Ads: Oldsmobile

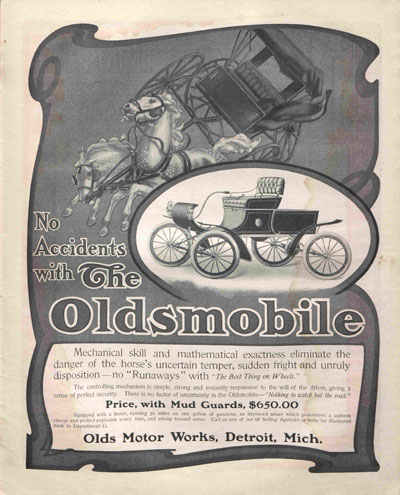

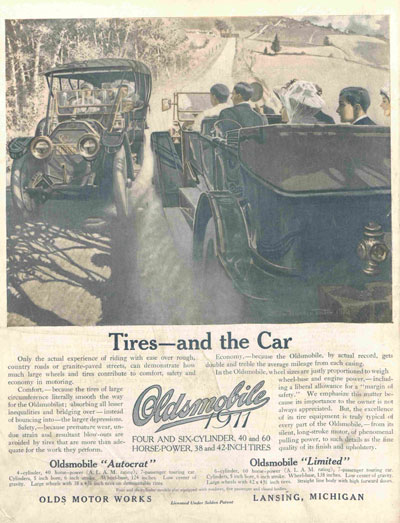

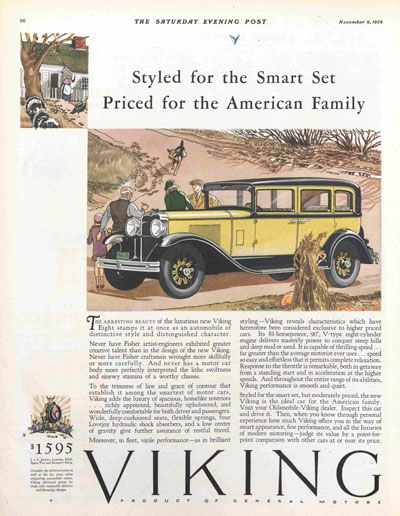

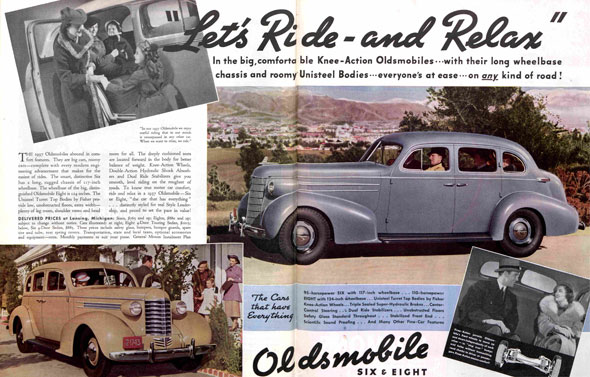

Like David Buick and Louis Chevrolet, Ransom Olds was fated to launch a car company that left him behind on its way to becoming a leading brand.

Olds was one of the originals, starting his company in 1897. The first automaker to use mass production, he produced 425 vehicles in 1901, which made him the country’s leading car manufacturer. But in 1904, the company’s board of directors wanted to move the line toward larger, more expensive cars. Olds wanted to continue producing his small, affordable models. In the end, he left Olds Motor Vehicle company to start over. Unable to use his name on a new brand, he chose his initials instead, and Ransom Eli Olds launched the REO Motor Car Company. (For more on the auto industry’s early years, check out Post‘s new special collector’s edition, Automobiles in America!)

His old company was acquired by General Motors in 1908, which positioned the Oldsmobile as a mid-priced brand.

In the decades that followed, the company introduced several innovations in its engine and transmission design. By the 1970s, it was producing America’s best-selling car. Yet within a few years, the Oldsmobile brand had lost its popularity, and in 2004 General Motors closed the Oldsmobile line.