A Busy Day for President Ford

Gerald Ford entered the White House under some of the most unusual circumstances in the history of the nation. After President Richard Nixon’s vice-president, Spiro Agnew, resigned, House Minority Leader Ford was nominated to take his place. Little did he know that he’d soon be assuming the presidency as well. With so many tasks before him, large and small, here’s a look back at one day 50 years ago where the new president had to fill some jobs, including his old one.

On August 1, 1974, Ford received some startling information from President Nixon’s chief of staff, Alexander Haig. Haig let Ford know that a damning recording related to the Watergate scandal would soon become public. It was apparent that the only two courses of action within the government were going to be an impeachment or a resignation, and either way, Ford should be ready to ascend to the presidency under the 25th Amendment. The tape went public on August 5; Nixon gave a televised speech to the nation on August 8 in which he announced his resignation, effective the next day. Ford assumed the presidency on August 9; he was sworn in with the oath of office in the East Room of the White House with Chief Justice Warren Burger presiding.

The situation was already rife with historic import. Ford was president, but hadn’t been elected to either the vice presidency or the presidency. That was the first (and thus far only) time that’s happened in the history of the United States. However, it was a brilliant demonstration of the system actually working. The 25th Amendment had codified how presidential and vice presidential replacements worked, and it was followed to the letter without unrest. Ford, ironically, by not being elected, became one of the best examples that democracy worked.

As the new guy in the big chair, Ford had to set about a number of important pieces of business. The major question, of course, was: Who would be his vice-president? Within the Republican party, there was a clear consensus. The majority wanted George H.W. Bush. A decorated pilot, a former member of the House of Representatives, a U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, and Chairman of the Republican National Committee, Bush had more bona fides that just about anyone else. However, there was also support for former New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. Rockefeller had also served in the administrations of FDR and Dwight Eisenhower and campaigned for the Republican presidential nomination on three occasions. If you look at Rockefeller’s list of positions, particularly on the environment, he’d probably be considered left-leaning by the standards of today.

On August 20, 1974, Ford opted to nominate Rockefeller for the vice presidency and offered Bush a role as chief of the U.S. liaison office in the People’s Republic of China. That essentially made Bush the U.S. ambassador to China (formal ambassadorship would resume in 1979). Bush accepted, and would later serve as Ford’s director of the Central Intelligence Agency beginning in 1976. Rockefeller’s nomination to the vice presidency was approved and confirmed by Congress, and he assumed the role on December 19.

The other significant move that Ford made on August 20, 1974, was an ambassadorial appointment. It became a subject of national interest because the appointee had been perhaps the most famous child star in American history. For the post of ambassador to Ghana, Ford nominated Shirley Temple Black. Known for her prodigious film and television career that began when she signed her first deal at age 4 in 1932, Shirley Temple sang, danced, and acted her way through shorts, films, and radio until her formal film retirement in 1950. That was the same year she married her second husband, businessman Charles Alden Black. She continued to work in TV in the late 1950s and early 1960s.

Later in the 1960s, Shirley Temple Black got active in California politics, running unsuccessfully for Congress in 1967. President Nixon appointed her as a delegate to the U.N. General Assembly in 1969. She had already impressed the administration, including Henry Kissinger, with her knowledge of West Africa. For Ford, it was an easy choice, even if some Americans had a hard time squaring the image of the curly-haired girl with the sharply intelligent diplomat she’d become.

As it turned out, Ford’s appointments, and presidency overall, didn’t last that long. He was defeated in the 1976 election by Georgia governor Jimmy Carter. However, his legacy remained as a person who was instrumental in maintaining the balance of power in the United States in a time of great turmoil. And while Bush may not have made it to the second-highest office in the land in 1974, he would get there in 1980 (as running mate to Ronald Reagan) before winning the presidency himself in 1988. Sometimes even busy historical days are also just history deferred.

Too Old to Be President?

Age has been a big factor in this election.

For the first time, two candidates in their 70s are running for the nation’s highest office. And as you’d expect, both parties are claiming the other’s candidate is feeble, disoriented, and making no sense — i.e., too old for the job.

But 70 years doesn’t mean decrepitude as it once did. “Threescore and ten” years was the lifespan the Bible allotted to a human, but today’s 70-year-olds are different. They’re generally healthier, more active, and less mentally impaired than their parents or grandparents were at that age (if they even reached that age). Can an older candidate be less competent because of age? Certainly. But incompetence can be found in candidates of any age.

Perhaps the concern with age issue is really a concern over health: can a 70-year-old endure the stress that comes with the Oval Office?

The chances are good for either candidate because presidents appear to be unusually hardy.

For example, the Republican Party tried to recruit Dwight Eisenhower to be their presidential candidate in 1948. He turned them down, concluding he would be unelectable. They expected Thomas Dewey — the candidate they chose instead — to serve two terms. Which would make Eisenhower 66 years old if he chose to serve in 1956, and the country wouldn’t want someone that old.

But Eisenhower ran in 1951 and won. Three years later, he had a heart attack, but entered the race again in 1955, and won again. After he left the White House, he continued to play a dominant role in the Republican party until he passed away at 78.

Gerald Ford was 61 when he assumed the presidency upon Nixon’s resignation in 1974. He lived 29 years more. Ronald Reagan, aged 69 years at his 1981 inauguration, served two terms and lived 16 years beyond that. George H.W. Bush was 64 when he entered the Oval Office in 1989. He lived another 29 years.

And of course, there’s Jimmy Carter, who was elected at the tender age of 52. Thirty-nine years later, he’s still with us, building homes for Habitat for Humanity.

It’s significant that, of the six presidents who have celebrated their 90th birthday, four — Jimmy Carter, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and George H.W. Bush — served in the past 50 years.

But the number of decades is just one way to consider age. We can also judge a president’s age relative to the average lifespan of his time.

Up to the 1930s, Americans could think themselves lucky if they reached their 65th birthday. But our lifespan has continually lengthened; since 1920, the average American has gained 25 years of life.

Historians have estimated that, in the centuries preceding the 1800s, the average human lived just 35 years. The number is surprisingly low because it is calculated from the ages of all deaths within a year. Nearly half of these deaths (46 percent) were among children under the age of five, which lowered the average age of mortality for adults.

One researcher has concluded that a more realistic average lifespan of a 20-year-old American in 1800 was 47 years — still not a long life. Which is what makes John Adams so exceptional. Adams became president at the age of 61 — fourteen years beyond his expected lifetime. And he lived 25 years beyond his presidency!

Adams’s son, President John Quincy Adams, lived to 80. Thomas Jefferson reached 83, and James Madison saw his 85th birthday.

Today, the average American lives 78.54 years. But an American male who reaches the age of 65, according to the National Center for Health Statistics, has a good chance of living another 19 years.

Which means either candidate might be likely to live to the age of 84 – or beyond.

It’s possible that presidents in their 70s will be looked on more favorably as the proportion of elders in the population increases. By 2060, a quarter of the U.S. population will be over 65 years and old, and the average American lifespan will have risen from 74 to 85 years.

Children today may live to hear candidates someday complain that their 100-year-old opponents are too old to be president.

Featured image: John Adams, Dwight Eisenhower, and Andrew Jackson, three of the older presidents when they assumed office (Adams: National Gallery of Art; Eisenhower: Wikimedia Commons; Jackson: whitehousehistory.org)

Considering History: George H.W. Bush and the Best and Worst of 20th Century America

First and foremost, the death of George Herbert Walker Bush is a human loss, the passing of an elderly man who lived a long and good life and will be mourned but also remembered and celebrated by his family, loved ones, and communities small and large. As with any death, those stages of grief, mourning, memory, and celebration should be respected and honored, in public eulogies as in every other way.

But former presidents are more than just private individuals, of course. They are among the most recognizable and prominent public faces of the nation, representatives of our history and identity. Remembering the histories to which their lives connect isn’t politicizing their deaths—it’s understanding what in us they help us see and analyze. And in Bush’s case, his public career and presidency illustrate some of the best and some of the worst of 20th century America, through a number of key themes.

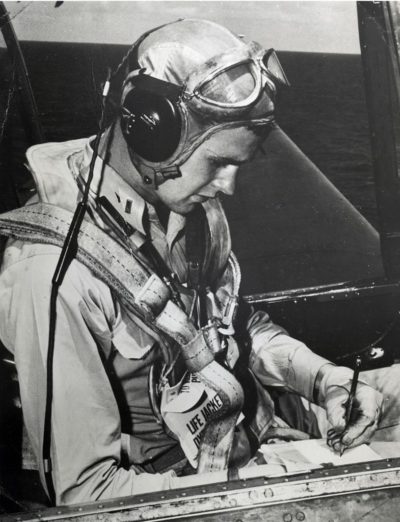

Take war, for example. Bush’s World War II service embodies “Greatest Generation” images and ideals. As the son of a wealthy New England family, Bush could certainly have avoided service if he chose; but instead, in June 1942, immediately after graduating from the prestigious Phillips Academy and turning 18, Bush postponed his college career to enlist in the U.S. Navy. He was a naval aviator before he turned 19, making him one of the youngest aviators in the service. He served impressively in the war’s Pacific Theater throughout the conflict, including his famous experience surviving a fighter crash and subsequently helping rescue other downed aviators.

Yet as president, Bush was connected to an example of the worst of wartime excesses. The first Gulf War was a controversial one in any case, driven by a combination of factors including international law (in response to Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait) and American energy interests. Moreover, Bush’s Ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, had tacitly supported Hussein’s planned invasion. And during the war, U.S. forces committed at least one serious violation of international law in their own right, bombing a Baghdad air raid shelter that they knew to be a civil facility and killing at least 400 Iraqi civilians. Perhaps such excesses are an inevitable part of war, but that makes them an inevitable part of Bush’s wartime legacy as well. Although so too, to Bush’s credit, is his decision to end the war without pursuing Iraqi forces to the capital, greatly reducing casualties as a result.

Bush’s broader foreign policy legacies are also complicatedly mixed. Bush was president during two of the most significant culminating Cold War events, the November 1989 fall of the Berlin Wall and the December 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union. By all accounts, Bush’s measured and pragmatic perspective and approach both contributed to these crucial changes and, perhaps most importantly, helped make sure that their democratizing effects could continue. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, for example, Bush met with Soviet General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev at a summit in Malta; some U.S. advisors believed the meeting to be premature, but Bush seemed to agree with Gorbachev that “We are just at the very beginning of our road, long road to a long-lasting, peaceful period,” and indeed the Malta conference among other steps helped produce that period.

Yet before and during his presidency Bush also took part in some of the worst of America’s 20th century foreign policy roles: as an active supporter of dictatorial regimes around the world. During his late 1970s year as CIA director, Bush helped suppress an intelligence report blaming Chile’s military dictatorship for the assassination of a Chilean dissident and an American woman working with him, leaking a false report instead. During Bush’s presidency, Zaire’s brutal military dictator Mobutu Sese Seko, a longtime ally of Bush (and of President Reagan before him), was the first African head of state to visit the White House. And even the controversial overthrow of Panamanian dictator Manuel Noriega was linked to such histories, as Reagan and Bush had supported Noriega’s rise to power as part of their broader Cold War strategy of supporting Central American right-wing dictatorships to oppose communist forces in the region.

On the domestic front, Bush has frequently been linked to conversations about civility and bipartisanship in American political and civic life. Exhibit A in those narratives is the handwritten letter that Bush left in the Oval Office for his successor as president, Bill Clinton; although Clinton had just defeated Bush in an acrimonious campaign, Bush’s letter did indeed embody not only a peaceful transition of power, but also a warm and collegial attitude toward this political rival and his incoming administration. In this way, as in his self-deprecating embrace of Dana Carvey’s impersonation of him (among other arenas), Bush did represent a far different political climate than that of 2018 America.

Yet in his prior, successful 1988 campaign for the presidency, Bush relied on an attack ad that embodied instead the worst of cynical and divisive partisan politics and national narratives. The infamous Willie Horton TV ad used the image and story of a frightening African American convicted rapist to indict Democratic candidate Michael Dukakis as soft on crime, and more exactly used racist and white supremacist fears to undermine Dukakis’s lead in polls and fundamentally shift the political and social conversations about the campaign. The ad has generally been attributed to Bush’s campaign manager, Lee Atwater, who apologized for it on his death bed; but Bush was the candidate for whom it was created and whose victory it helped assure, and he is thus intimately implicated in one of the century’s most egregiously divisive and bigoted political moments.

These are some a few examples of Bush’s complex and contradictory legacy, which could also include on the one hand the civic ideal of the “Thousand Points of Light” and on the other the dark reality of Bush’s refusal to support gay Americans at the depths of the AIDS epidemic. Such contradictions are part of the story of George H.W. Bush but also of late 20th century America, and remembering them as we mourn his passing and celebrate his life helps us better understand those collective histories and their 21st century legacies.

News of the Week: Allergy Season, the First Man on the Moon, and Why Lobsters Are Gross

My God, the Pollen!

I’ve been coughing so much this past week I feel like I should sprinkle the word COUGH throughout this column just to convey to you how much I’m doing it. Endless yacking from pollen, which brings on headaches and a burning throat and just exhausts me, both physically and mentally.

There are remedies, of course, including medications and herbs. I always get a kick out of experts who tell you to avoid allergy triggers by staying inside and closing all the windows and doors. In weather that’s 80 degrees and humid? That’s like when they tell you to wear long-sleeve shirts and long pants tucked into your socks to avoid mosquito bites. Hey, why not walk around in June wearing a suit of armor and a hazmat suit? It’s logical, but not feasible.

I wouldn’t wish this coughing on my worst enemy. Well, maybe my worst enemy, because I don’t see the need for people I dislike to be comfortable. But not anyone else.

Humidity, bugs, sunburns, allergies. Tell me again why people like the warm weather months?

First Man

Ryan Gosling plays astronaut Neil Armstrong in the upcoming movie First Man, which of course refers to Armstrong being the first man to set foot on the moon in 1969. Here’s the trailer. The movie opens on October 18.

Woman vs. NASA

I didn’t think there would be two stories about Armstrong this week, but there are, and one of them involves a moon dust lawsuit.

Laura Murray Cicco received a vial of moon dust from Armstrong himself when she was 10 years old. Her father and Armstrong were both members of an aviation club, and Armstrong gave the vial as a gift to the girl. She even received a handwritten note from him along with it. But NASA says it’s their policy that anything from the moon is the property of the U.S. government, so Cicco has decided to pre-empt any lawsuit that the space agency might bring to her by suing them first.

Oddly, this is the second lawsuit involving moon debris in the past year. In 2017, a woman won another lawsuit against NASA and got to keep a bag of moon dust from Apollo 11 that she won in an auction for $1.5 million. She auctioned off the bag at Sotheby’s.

Breaking News: The Raccoon Is Safe

If you’re not on social media and don’t have a Google Alert for “raccoons,” you may have missed the news this week that a raccoon was trapped on the side of the UBS building in St. Paul, Minnesota. There was even a live stream of the animal’s adventure watched by the entire world. I’m happy to report that the animal made it to the roof like Spider-Man and was taken in by wildlife experts, who fed it and then released it into the wild.

We now return you to your regularly scheduled non-raccoon programming.

Happy Birthday, George H.W. Bush

The former president hit a milestone that no other president in history has ever reached before: he turned 94 on June 12 (Gerald Ford and Ronald Reagan both died at the age of 93). This was great to see after so many recent health problems for the 41st commander-in-chief.

The Bush family also celebrated the June 8 birthday of H.W.’s wife of 73 years, Barbara Bush, who died on April 17 at the age of 92.

He won’t be alone at that age for long, though. Former president Jimmy Carter turns 94 on October 1.

RIP Anthony Bourdain, David Douglas Duncan, Eunice Gayson, Danny Kirwan, Maria Bueno

There probably isn’t much left about food and travel writer/TV host Anthony Bourdain that you haven’t already read in the various obituaries, so I’ll talk about something that hasn’t been mentioned that much in all of the tributes written this past week: his fiction. Bourdain is known and rightly praised for nonfiction books like Kitchen Confidential, A Cook’s Tour, and The Nasty Bits, but he also released two crime novels that are worth reading, Bone in the Throat and Gone Bamboo. Bourdain also has a collection of short crime fiction titled The Bobby Gold Stories and co-wrote two graphic novels.

And here’s the 1999 New Yorker story that pretty much started Bourdain’s writing and TV career, “Don’t Eat before Reading This.”

David Douglas Duncan was an acclaimed photographer known for his iconic photos of World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War. He died last Thursday at the age of 102.

Eunice Gayson was the first Bond girl. She was 007’s girlfriend Sylvia Trench in the first two films, Dr. No and From Russia with Love. She didn’t do any more Bond films after that, but went on to appear in other movies and TV shows, including The Avengers and The Saint. She died last Friday at the age of 90.

Danny Kirwan was one of the early members of Fleetwood Mac. He played guitar for the band’s albums from 1968 to ’72. He died last Friday at the age of 68.

Maria Bueno was a professional tennis player who won 19 Grand Slam titles and 589 tournaments overall. She was ranked No. 1 four times in her career and carried the torch for Brazil during last year’s Summer Olympics. She died last Friday at the age of 78.

This Week in History

Judy Garland Born (June 10, 1922)

The Post’s Cameron Shipp wrote a terrific profile of the troubled star for the April 2, 1955, issue, “The Star Who Thinks Nobody Loves Her.” If you do indeed love Garland, it’s a must-read.

Shipp, by the way, was dead himself only 6 years later, on August 20, 1961. He was 57.

President Reagan’s “Tear Down This Wall” Speech (June 12, 1987)

This week’s meeting between President Trump and North Korean president Kim Jong Un in Singapore took place on the 31st anniversary of Reagan’s speech in Berlin.

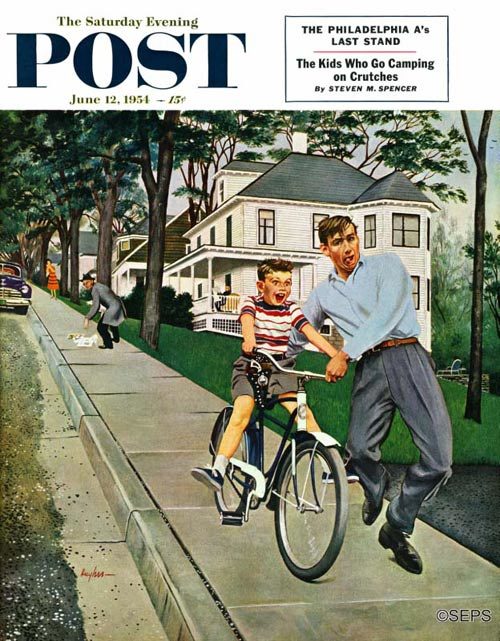

This Week in Saturday Evening Post History: Bike Riding Lesson (June 12, 1954)

Several years ago, I was walking to the train station through a residential neighborhood. A group of kids on bikes rode past me, laughing and being generally boisterous. As I walked past a house a moment later, I noticed a young boy sitting on his front steps, his bike sitting on the ground next to him. He saw me coming and waved to me. I waved back and he asked me, his lip quivering, “Mister … can you teach me … how to ride a bike?” My heart broke, because I knew that the only thing in the world this kid wanted at that moment was to know how to ride a bike so he could go off and have fun with the other kids. I explained to him that I was late for the train and couldn’t stop, but maybe he could get someone in his family or a friend to teach him.

I thought of that after finding this cover by George Hughes.

George Hughes

June 12, 1954

Today Is National Lobster Day

I don’t understand lobsters. Actually, that makes it sound as if they speak and I don’t understand what they’re saying, so let me clarify: I don’t understand why people enjoy lobsters.

This makes me an anomaly where I live, a coastal town known for its seafood, water, and beaches. But at least I’m consistent, because I don’t like beaches, and I don’t know how to swim either.

I worked in restaurants for many years and often had to deal with lobsters and their equally gross cousins, shrimp. I hated dealing with and cooking lobsters when people ordered them, and I particularly hated cleaning shrimp. I couldn’t understand why people would want to eat these bug-like things that not only didn’t taste good to me, but were pretty disgusting in their pre-cooked form. (They’re pretty disgusting in the cooked form too.) Some day, remind me to tell you all about the veins of shrimp and how I almost sliced my finger off cleaning one.

But by all means, I hope you enjoy today, in whatever form you like your lobster: Newburg, bisque, roll, or lobster salad. You can even put lobster in your mac and cheese, or as I call it, “how to ruin mac and cheese.”

COUGH.

Next Week’s Holidays and Events

Father’s Day (June 17)

If you really want to give your dad something special, and you don’t want to go the usual tie/cologne route, how about some baubles he can put in his beard, a yodeling pickle, or a membership to the Salami of the Month Club?

Of course, Father’s Day is this Sunday, so these gifts will arrive late, but as the old saying goes, I’d wait forever for a yodeling pickle.

Summer Starts (June 21)

If you hate summer, the countdown to fall begins now. Only 93 days!

National Selfie Day (June 21)

Isn’t every day Selfie Day? What we really need is a No Selfies Day. Oh wait! We have that, too.

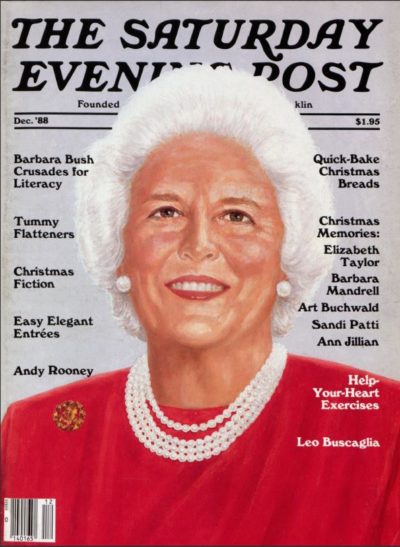

Remembering Barbara Bush

The Saturday Evening Post was saddened to learn of the passing of First Lady Barbara Bush, wife to President George H.W. Bush and mother to George W. Bush.

An illustration of Mrs. Bush graced our December 1988 cover. Inside, we featured a story of her tireless efforts to fight illiteracy. She became involved with literacy when her husband became vice president in 1980, and her efforts and influence grew from there. She endorsed and supported the Project Literacy U.S. campaign, served on the board of Reading Is Fundamental, and convinced the McGraw-Hill CEO to devote his retirement years to literacy. Shortly after this article was published, she launched The Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy.

The story also illustrates many of the qualities that Mrs. Bush was known for: “Warm and unpretentious, she is skilled at putting people at ease, not in a calculating way, but because it is natural for her. She is moved by people and their hopes and fears and joys and problems. Most of all, she is moved by new learners, by their courage and determination.”

Inaugural Addresses: the Good, the Bad, and the Confused

This week, when a new president is sworn into office, America will hear its 58th inaugural address. The country has been listening to presidents’ introductory speeches since the tradition began 228 years ago with George Washington.

It’s surprising that we remember so little of those speeches.

We know the inspiring words of Lincoln’s second inaugural address: “With malice toward none, with charity for all…” And most Americans are familiar with the phrase, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” even if they don’t know it came from Franklin Roosevelt’s first inaugural address. A generation was inspired by John Kennedy’s inaugural address, with its memorable line, “ask not what your country can do for you …”

The inaugural address has been the president’s chance to present the vision and goals for his administration, but it has also been a time to express his trust in the country and its people. This is how Theodore Roosevelt articulated it: “We have faith that we shall not prove false to the memories of the men of the mighty past. They did their work, they left us the splendid heritage we now enjoy. We in our turn have an assured confidence that we shall be able to leave this heritage unwasted and enlarged to our children and our children’s children.”

The presidents have also addressed the partisan divisions created by the electoral process. In 1989, George H.W. Bush noted the divisiveness in the U.S. “We have seen the hard looks and heard the statements in which not each other’s ideas are challenged, but each other’s motives. And our great parties have too often been far apart and untrusting of each other… the old bipartisanship must be made new again.”

It was the same message delivered by Thomas Jefferson back in 1801. Having won the presidency after a bitter campaign, he acknowledged that the election had produced strong words and hard feelings. But the election had been decided according to Constitution, and all Americans would “unite in common efforts for the common good. All, too, will bear in mind this sacred principle, that though the will of the majority is in all cases to prevail, that will to be rightful must be reasonable; that the minority possess their equal rights, which equal law must protect, and to violate would be oppression. Let us, then, fellow-citizens, unite with one heart and one mind.”

No president made a more eloquent appeal for national unity than Abraham Lincoln. At his first inauguration, he appealed to the southern states not to secede but to remain in the Union.

“We are not enemies, but friends. We must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break our bonds of affection. The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.”

It hasn’t always been easy for presidents to find the right thoughts for the occasion, or the best words to express them. Some presidents tried too hard to present a tone of dignity and statesmanship. Take John Quincy Adams, for example, who launched his address with this overblown monster of a sentence:

“In compliance with an usage coeval with the existence of our Federal Constitution, and sanctioned by the example of my predecessors in the career upon which I am about to enter, I appear, my fellow-citizens, in your presence and in that of Heaven to bind myself by the solemnities of religious obligation to the faithful performance of the duties allotted to me in the station to which I have been called.”

William Henry Harrison put a lot of effort into his inaugural address and produced the longest speech ever delivered, even after Daniel Webster had edited it. It took Harrison two hours to deliver his address on a cold, wet day.

Warren Harding had been criticized for having little qualification for the office other than looking like a president. His speeches were filled with clichés and platitudes, and he was dismissed as less than bright. Then, in his inaugural address, when he said, “we must strive for normality to reach stability,” he accidentally said “normalcy,” which wasn’t a common word in 1921. His critics never let him forget it.

Why have some speeches inspired Americans with hope and purpose, while others have left them cold? According to a Post editorial from January 20, 1945, called “Has Our Ideology Run Out of Words?,” the empty, forgettable speeches, so common in modern America, come from a lack of direction. A speaker can reach the mind and hearts of Americans only if his goals are clear and positive. So, in this sense, an inaugural address is not simply a tradition. It is a weather forecast for the next four years.

Has Our Ideology Run Out of Words?

Originally published January 20, 1945

We were thinking the other day about the poverty of good phrasemakers in our public life, and it occurred to us that the probable reason for this poverty is our lack of a coherent sense of direction. Wading through the pages of The Congressional Record, you occasionally come across a competent speech floating in the bouillabaisse, but when you lay the Record down or when you finish reading a newspaper report of a speech, you feel like a man who walks home from a musical show slightly annoyed because there wasn’t a whistleable tune in the whole score. There is nothing to remember, nothing to clasp to the breast as if it were a happy discovery, nothing to cherish as if it were a bride or a new baby; only fustian and clichés set like crossbeams amidst an uninspired framework that a carpenter might toss up for a neighbor on a vacation week end.

Some of our public men, among them President Roosevelt, have a pleasing way of talking which makes commonplace phrasing, at the time of delivery, sound amazingly good, but the effect is theatrical and it wears off quickly. General MacArthur occasionally comes up with a rememberable sentence, but his phrasing is, on the whole, discouragingly florid. At the far end of the scale we have Secretary Ickes, whose phrasing and irritating delivery have done much to make unpopular both the English language and honesty in public office.

What brought all this up was a single sentence that cracked like a snapped thong during the Commons uproar on the civil disorder in Greece: “Democracy is not a harlot to be picked up in the street by a man with a tommy gun.” This masterful expression was molded in a man’s brain in the heat of debate — unless Mr. Churchill had it penciled on his cuff for just such an emergency — and it was one of the finest examples of forensic hip-shooting we have ever come across. Mr. Churchill, of course, is the master phrasemaker of the era. In the worst of crises he has been ready with phrases which have heartened Englishmen and men all over the world who were concerned with England’s fate. Anyone can remember at least two or three of them. Has Mr. Churchill a sense of direction? A Prime Minister of Great Britain cannot afford to be without one, and Churchill has stated his bluntly, to the annoyance of those who dislike candor: he didn’t, you may recall, become His Majesty’s first minister to preside over the liquidation of the Empire.

America’s destiny was not always as clouded as it is today. What we seem to be seeking is security, and security is a negative goal. In the Revolutionary period, and thereafter, we wanted not only security but more land to occupy. And in that era we had some historic phrasemakers, among them Washington and Jefferson. During the Civil War, when we gambled security to solidify the states into a true Union, there emerged Lincoln, a self-educated prairieman whose phrases added dignity to the language of America and to the language of free government. We haven’t seen his like, or anyone approaching his like, since then, unless it was Franklin Roosevelt stating, on March 4, 1933, that we had nothing to fear but fear itself. But, at that time, Franklin Roosevelt had a sense of direction.

Offhand, you might say that good phrasemaking was a symptom of healthy reaction to national danger, but, unfortunately, that diagnosis doesn’t fit the present situation. The people are in danger, and they are often spoken down to by politicians in terms of the baseball diamond, or of the radio commercial, or in the omniscient patter of the syndicated columnist. Our ideals are the victims, often of slang, but more often of good words which have lost their freshness through too much handling.

We don’t say that good phrases will confer upon a nation a sense of direction; rather, we feel that good phrasing among political leaders is, historically, symptomatic of a nation whose leaders have plotted a firm course. Words, even brave words, aren’t bullets or an adequate substitute for bullets, but they can supply men with the motivation for shooting bullets and for facing the bullets of an enemy. Sincerely and competently used, they can make nations do many fine things. They are the currency by which we conduct our trade in precious thoughts, and our currency is presently debased from slovenly phrasing and incessant repetition. We shall feel a good deal better when a few genuinely memorable phrases emerge from the mouths of our statesmen.

Featured image: Wikimedia Commons, SSgt Mark Fayloga / defenseimagery.mil, public domain