Norman Rockwell and the Post: A Fruitful Relationship

© SEPS

My grandfather once said, “The Post is my best and only opportunity to express myself fully.” He liked to come up with his own stories and tell them his way — and the Post covers were the best way for him to do that. With other illustration work, he was forced to rely on and stay true to someone else’s story. Without the unique opportunity that The Saturday Evening Post presented to him for so many years, it could be argued that Norman Rockwell would not have evolved into the incomparable and beloved storyteller we know today.

Pop, as we called him, always wanted to become a great illustrator — he was driven from the moment he started sketching while his father read Charles Dickens to the family, and later studying the work of other artists: “You start by following other artists — a spaniel. Then, if you’ve got it, you become yourself — a lion.”

His dream was to do a cover for The Saturday Evening Post, but he was haunted by doubts. Only the very best, like J.C. Leyendecker and Coles Phillips, did covers for the Post.

He began to sit alone in the studio he rented with his friend, the noted cartoonist Clyde Forsythe, a copy of the Post spread out before him, allowing himself to dream. He dared to visualize a picture he had painted on its cover. He imagined how many people would see it — one million, even two million? He pictured his name in the lower-right-hand corner. What would it be like if he were the man he wanted to be, a famous illustrator, adored by female fans, his covers displayed on newsstands and tucked in the mailboxes of families around the country? He pictured children fighting over who would get to see the cover first and explore all its details. He even saw himself dining with the Post’s larger-than-life editor, George Horace Lorimer.

One day Clyde found him on the sofa, suffering over the fact that none of this was even close to becoming a reality. Clyde had to convince Pop that he was indeed good enough to attempt a cover. Don’t be intimidated, he said: “Lorimer’s not the Dalai Lama.”

So my grandfather got to work. Two ideas came to him, conjured up from the kind of covers he had admired on the Post. The first was a Gibson Girl kind of painting with a dashing man bending over a sofa to kiss an irresistible, but removed, high-society woman; the second, a young ballerina bowing before an audience in a dramatic spotlight. Clyde took one look at the paintings and exclaimed dryly, “C-R-U-D.” The ballerina, he said, looked like a “tomboy who’s been scrubbed with a rough washcloth and pinned into a new dress by her mother. Forget about what you think the Post is looking for and paint what you do best — kids.”

Pop followed his friend’s advice, completing several paintings and rough sketches to take to the offices of The Saturday Evening Post. For his big meeting, my grandfather bought a brand-new black hat and new suit in a fashionable gray herringbone tweed. He had a custom-made “suitcase” created to take the paintings on the train to the Post in Philadelphia. The problem was, the case looked more like a small black casket. Despairing thoughts followed him all the way. But miracle of miracles, Lorimer accepted two finished paintings and okayed three sketches for future covers. His first cover, Salutation [also called Boy with Baby Carriage], would appear on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on May 20, 1916 — Pop was only 22 years old.

My grandfather used one of his favorite models, Billy Payne, for all three boys in this first cover. The boy pushing the pram is fully realized and rendered, but the other two boys are poorly done. He should have used three distinct boys to model for the painting. And the dark hollow of the pram and barely visible baby were probably the result of nerves. Pop must have been anxious about painting his first Post cover and perhaps couldn’t quite deal with getting an actual baby as a model with its very real wriggling and crying to contend with.

April 16, 1927

© SEPS

In later years, he often recalled the fun and hard work of pitching his ideas to Lorimer. He would place the sketches in front of Lorimer on his desk and then act them out to bring the whole picture and story to life in an exciting way:

I’d get up from the chair, shake myself and point to one of the sketches on the desk. “Springtime,” I’d say, “a little boy perched on a stump playing a flute.” And I’d sit on the edge of a chair, pull up my legs from the floor in a graceful pose, and make believe I was blissfully blowing a flute. “The kid’s happy,” I’d say. “It’s spring. The sun is warm upon his neck; the bees are buzzing in the flowers. And the little animals are dancing in a ring about the stump. A rabbit, a duck, a frog” — I’d kick up my heels and dance around the chair — “a turtle, a squirrel, an owl, a grasshopper. It’s spring. Everybody’s joyful.”

“Good,” Mr. Lorimer would say, scribbling OKGHL on the side of the sketch.

That particular sketch ended up as Springtime, 1927, the April 16, 1927, cover [above].

My grandfather’s time at The Saturday Evening Post can be divided into three periods corresponding to the three editors, along with one significant art editor, who oversaw the magazine until my grandfather quietly resigned in 1964. The first period, of course, was dominated by the commanding presence of Lorimer. Pop remembered always being greeted by Lorimer standing behind his desk, silhouetted by the light from the two expansive windows behind him. “The Great Mr. George Horace Lorimer, the baron of publishing,” as my grandfather would affectionately refer to him, had a strength and unwavering decisiveness that Pop so admired. Lorimer’s square jaw and commanding eyes projected power softened with kindness. Over the years, Lorimer became a father figure and mentor to my grandfather, even as Pop remained somewhat in awe of the man. (He even sought Lorimer’s approval when marrying his second wife, my grandmother Mary.) When Lorimer resigned in 1936, it was the end of an era.

The second period was a short and difficult one for Pop. Always in fear of the Post dropping him at any moment despite his growing fame, he felt even more precarious when Wesley Stout came on board as editor, succeeding Lorimer. Stout lacked Lorimer’s decisiveness. He seemed to look for what was wrong in each of my grandfather’s paintings instead of what was right. This whittled Pop’s confidence down until he didn’t feel good about any of the work he was turning in.

But five years later, Ben Hibbs replaced Stout as editor. He was a Midwesterner, much more casual, and he genuinely liked my grandfather’s work. He resurrected The Saturday Evening Post at a time when the magazine desperately needed it. He had the cover redesigned so that full paintings were shown, not just vignettes of one or two people with almost no background. The logo was streamlined into a more modern font in the top-left corner. This freed Pop to take his stories to a whole new level of detail, atmosphere, and character. And Hibbs supported Rockwell. He was the one, after all, who enthusiastically accepted and championed the Four Freedoms, publishing them inside the Post after the government rejected them. (The government would later relent, touring the paintings around the country to raise money for war bonds. The exhibition would raise more than $132 million.)

March 6, 1948

© SEPS

While Hibbs was editor, Ken Stuart came in as art editor in 1945, muddying the waters somewhat. He is credited with changing the direction of the content of the covers, moving them toward the celebration of America and loftier, more expansive ideas. But Stuart was a small man with a tremendous ego; he wanted to dictate ideas to his artists and control them. He had been an illustrator himself before becoming an art editor and perhaps felt entitled to have that much input. But my grandfather felt that Stuart over-directed at times. Their relationship was conflicted at best. The low point in their working relationship came when Stuart went so far as to paint a horse out of one of Pop’s covers, Before the Date, September 24, 1949, without telling him.

Pop threatened to leave the Post. And my grandmother, Mary, was absolutely furious; she had never liked Stuart. But things settled down after it was arranged that Bob Fuoss, the managing editor, and Hibbs would oversee all matters regarding my grandfather. Pop’s attitude then seemed to soften toward Stuart. He even did what he could to butter him up, inviting him to my parents’ New York City wedding in the ’50s.

© SEPS

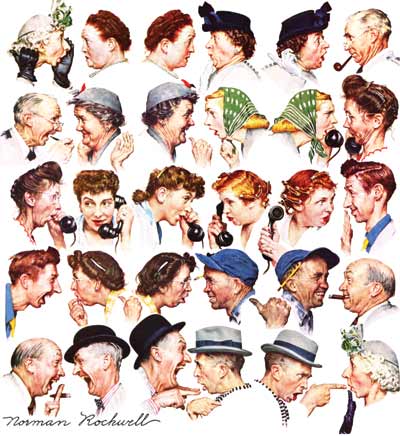

Still, that long-ago bitterness between the two men lingers today. Stuart claimed that Pop “gifted” several paintings to him, Saying Grace, The Gossips, and Walking to Church. No communications were found from my grandfather to Stuart other than Pop asking for his paintings to be returned in the ’50s and Stuart refusing this request, citing company policy. My grandfather felt that Stuart simply took the paintings out of the Curtis building one day and held on to them. The Stuart sons recently sold Saying Grace, my grandfather’s most popular cover, and the two other paintings at Sotheby’s for $57.3 million, a figure that would have astonished and probably embarrassed my grandfather.

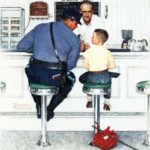

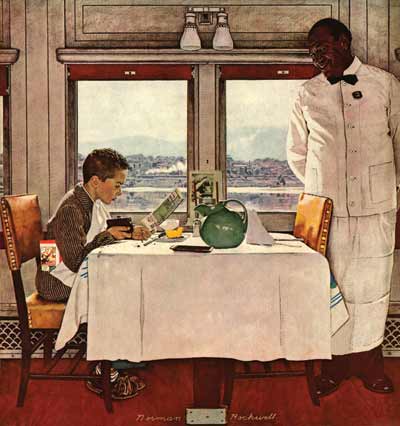

Most people today do not realize that during Pop’s tenure, The Saturday Evening Post prohibited its artists from painting people of ethnicity in any role other than a subservient one. This never sat well with my grandfather. He would sneak African Americans and people of other ethnic backgrounds into his paintings where he could — Statue of Liberty, July 6, 1946, for example. He cleverly turned this policy on its head in his December 7, 1946, cover, New York Central Diner. In it, a young boy in the train’s dining car is trying to figure out the check. But it is an African-American man, the waiter, who is the heart of this painting. The viewer’s eye goes to him because his presence is so immediately felt; he radiates such kindness and amusement at the boy’s dilemma.

December 7, 1946

© SEPS

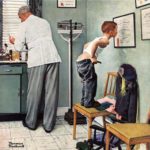

In my grandfather’s paintings, everything is said without words. The entwined legs of the two lovers in Voyeur, August 12, 1944 (page 39), reveal a quiet, unspoken, and immediate intimacy — and are the most prominent visual — though the little girl in red sneaking a look at them is sharing in their secret. It is one of my grandfather’s more intimate works, yet it takes place in a very public space, the brightly lit passenger car of a train. This contrast makes the cover touching and effective. The exposing overhead light doesn’t matter to the two lovers who are in their own private world, not even noticing the little girl leaning over the seat in front of them. We feel we are an amused, unseen observer on that train. Note the contrast between the young woman’s polished, stylish shoes and the soldier’s lived-in service boots.

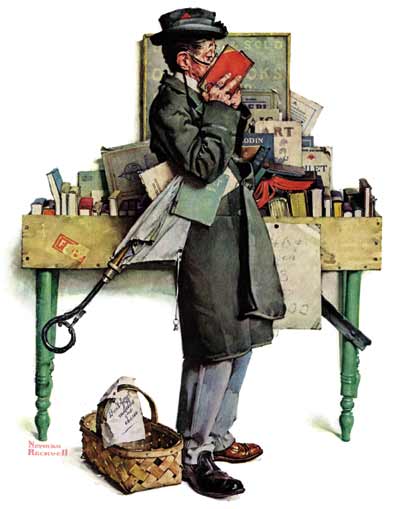

Like Van Gogh, Norman Rockwell was a master of shoes. Shoes can sometimes reveal more about the real life of a character than the face — the wear and tear, even with a good polish, still remains. One could say that the sole reveals the soul. Faces can hide aspects of personality through façades, cosmetic artifice, glasses, expressions, etc. There are many instances of Rockwell’s quiet focus on shoes in the Post — Breaking Home Ties, Tattoo Artist, Rosie the Riveter, The Game (April Fool 1943), New Year’s Eve, Willie Gillis Home on Leave, Hat Check Girl, The Cover Girl (Double Take), Dreams of Long Ago, Star Struck (Boy Gazing at Cover Girls), First in His Class, Full Treatment, Bookworm — as well as in advertising such as Crackers in Bed from the Edison Mazda series, and the list goes on and on. Bookworm actually shows a man wearing two entirely different shoes — a perfect, subtle way to show that this man is in his own world and too distracted to worry about matching shoes!

August 14, 1926

© SEPS

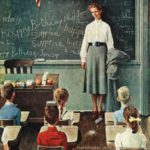

My grandfather loved to paint older people and children because of the clear contrast they represented: the old visited alongside the new, the unrelenting process of aging that we all have to move through. An older face reveals the trials and tragedies of a full life. There is either a softening or hardening of the features that occurs over time and forever etches itself onto the face — less artifice, even less of an attempt to hide the truth, the failures, the secrets and dreams. Children have an essential purity of reaction and an often unsuppressed sense of play, adventure, and possibility.

Pop always wanted to “get the feel of a place” that he was going to paint. He searched for the smallest details that would make his picture “ring true,” including the actual attire, props, and accessories of the period. That is what makes it so much fun to explore his paintings. Every detail is carefully chosen, a clue, a secret that is connected to the story. He was a “method” actor and director before anyone knew what “method acting” was. Many of his paintings and covers became a sort of sense memory exercise, capturing the atmosphere of the scene he had immersed himself in — whether the smells, sounds, and visuals of a prize fight in New York City or a blacksmith’s shop in a small town in Vermont.

© SEPS

All great art is a search for what is true. And Pop’s entire career was bound up in completing that search. In one example, he spent hours in Louisa May Alcott’s home for his series on Little Women, exploring the attic where she used to do her writing and contemplation. In another, he traveled to Mark Twain’s childhood town of Hannibal to prepare for illustrating Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn. He even went to the extreme of being left alone in Tom Sawyer’s famous cave, where he sketched alone by the light of a flickering lamp.

Rockwell’s vivid imagination was the engine that drove him all those years, an imagination that never tired. But it was often a constant struggle because of periods of self-doubt, and the fear that there was a lack of expansion and growth in his work. It is indeed a revelation to see the progression of his work — to see his vision, technique, and storytelling skill deepening and expanding over the 322 covers he did for the Post between 1916 and 1964. One marvels at his refusal, successful as he was, to stay in one place.

Yet, even as he grew as an artist, his core values never changed. Through almost half a century with The Saturday Evening Post, his work was always rooted in his central belief in the goodness in people. His message: We are struggling, celebrating, learning, and growing each day, and we are all in this together. That is what lives in the best of my grandfather’s work and in the best of all of us.

“It is no exaggeration to say simply that Norman Rockwell is the most popular, the most loved, of all contemporary artists,” Post editor Ben Hibbs said. “While the face of the world was changing unbelievably, Norman has amused, charmed, and inspired a great many millions of Americans. The fact that he has managed to capture the hearts of so many people is easy to understand when you know him, for somehow Rockwell himself is like a gallery of his paintings — friendly, human, deeply American, varied in mood, but full, always, of the zest of living.”

Click images to enlarge:

August 12, 1944

© SEPS

April 16, 1927

© SEPS

March 6, 1948

© SEPS

December 7, 1946

© SEPS

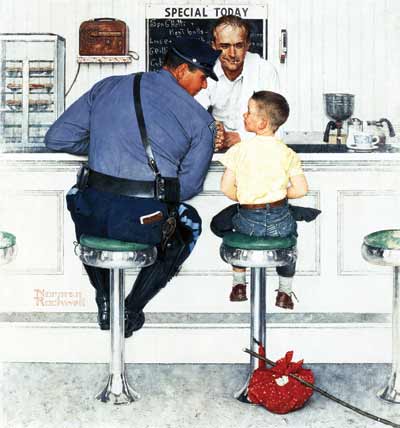

September 25, 1954, © SEPS

August 14, 1926

© SEPS

© SEPS

March 6, 1954.

© SEPS

March 17, 1956

© SEPS

March 15, 1958

© SEPS

August 22, 1953

© SEPS

Celebrate Women Artists: Sarah Stilwell-Weber

Sarah Stilwell-Weber was one of The Saturday Evening Post’s most sought after artists. She even turned down Post editor George Horace Lorimer’s offer to have regularly scheduled pieces because she didn’t want to work on another’s deadline. Between 1904 and 1925, her work was featured on over 60 covers of both the Post and The Country Gentleman (a sister publication of the Post).

A student of famous illustrator Howard Pyle and the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, one of the top art schools in the country, Stilwell-Weber captured a lighter side of the Victorian Era and the early 20th century in her work. Her young subjects were often on the move, playing games and exploring the world around them. Her mentor, Howard Pyle, told her never to marry, as it would interfere with her artistic life. However, she ignored him and married anyway.

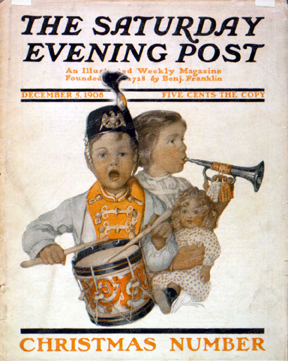

While the children are forming their own marching band, Mom and Dad wonder if Santa takes returns.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

December 5, 1908

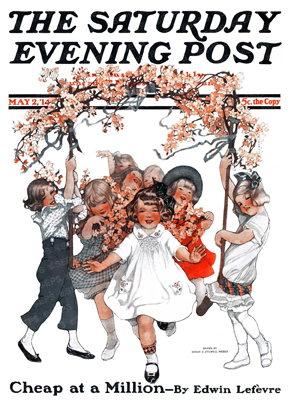

Forget flower crowns, these girls made a flower cape for their May Day parade grand marshal.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

May 2, 1914

Is there anything better than splashing in waves, soaking up sun, and building sand castles?

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

August 1, 1914

In the early 1900s, the Post covers were printed with a “duotone” two-color process: black and another color, usually red. This process is what makes the umbrella, flowers, and rosy cheeks on this little girl and her doll pop.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

September 4, 1915

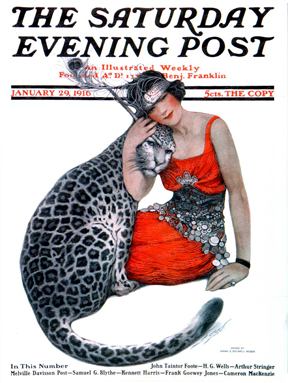

House cats are just too tame. This stylish young woman dared to make a leopard her pet.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

January 29, 1916

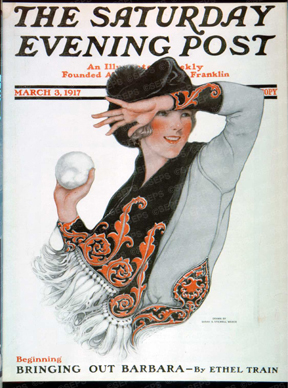

While many Post covers just show portraits of pretty young women, Stilwell-Weber adds life and movement to the traditional medium. This woman joins in the children’s fun after a stray snowball almost hits her.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

March 3, 1917

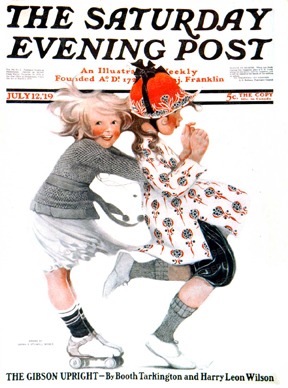

Rolling her way straight into your heart, this tot on wheels is ready for a hug.

Sarah Stilwell-Weber

July 12, 1919

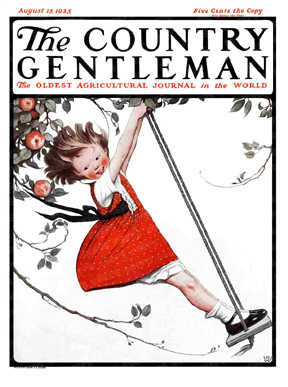

With that mischievous grin, this little one could be gathering momentum to jump or complete a loop-de-loop over the tree branch.

Sarah Stiwell-Weber

August 15, 1925

The Post and the Parks

Library of Congress

The National Park Service was formed by an act of Congress on August 25, 1916. Prior to that, most of our national parks fell under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Interior (DOI), which was underfunded and responsible for eight different divisions that managed, among other things, patents, Indian affairs, education, railroads, and the census.

Some parks were staffed by the U.S. Army, which had to enforce laws against poaching, grazing, and vandalism. Other sites were managed by civilians. National monuments had minimal staffing. Historic battlefields were run by the U.S. War Department, whose interest in maintaining these sites was low on its list of priorities.

By 1916, thanks to the Model T, millions of Americans actually had the means to visit the parks. But the parks were poorly maintained — many had only rough dirt roads. At the core of the problem was a fragmented management system that couldn’t share resources or information from one park to the next. “The present situation is essentially that of a city with a dozen splendid but largely undeveloped parks, each of them under a separate management,” the Post commented in an editorial from February 1916. “Of course no city would tolerate any such absurd arrangement. It would immediately establish a park board or bureau to manage all the parks coordinately.”

One of the biggest challenges was a lack of agreement on whether conservation meant protecting park land for its wilderness or usable resources. The dispute came to national attention in 1913 when a valley in Yosemite Park was dammed to provide water supply for San Francisco. Fears that the parks’ resources would be squandered prompted the drive to unify the parks.

Post editor George Horace Lorimer was a fierce supporter of the National Park Service bill, which proposed a unified system to run all the nation’s parks and monuments from within the DOI. In the year before the bill was finally passed, he ran no fewer than seven editorials endorsing it, sometimes as frequently as two weeks apart. The Post’s nature writer, Emerson Hough, also wrote in support of conservation and the parks. And his “Made in America” series in 1915 promoted the parks to American travelers who wouldn’t be vacationing in war-torn Europe.

In the aftermath of the bill’s passage, many credited the Post for its drumbeat of support: As Richard B. Watrous, secretary of the American Civic Association, said in a statement before the House of Representatives after the bill’s passage in April of 1917, “I might cite The Saturday Evening Post, which has had an editorial in it every two or three weeks for the past three months by its managing editor, Mr. George Horace Lorimer in very marked approval of the idea of having a national park service.”

Click the blue headlines below to read three of those impassioned editorials:

National Park Service — January 1, 1916

In 1916, Post editor George Lorimer wasted no time voicing the magazine’s support for the formation of a National Park Service to unify and manage the nation’s four dozen or so parks and monuments, which at that time were maintained separately. The following editorial appeared in the Post on New Year’s Day of that year.

Parks for Posterity — February 12, 1916

In February of 1916, Post editor George Lorimer showed his support once again for the passage of the National Park Service Organic Bill of 1916, which would establish the NPS as a bureau within the Department of the Interior. In “Parks for Posterity,” he argues that the “wisdom of this plan is so self-evident that no room is left for argument.”

National Park Service — March 18, 1916

In the Post of March 18, 1916, George Lorimer compared the success of Canada’s national park system to the relative failure of America’s parks, adding a note of patriotism to his arguments in support of the creation of the U.S. National Park Service. He contended that it wasn’t a question of quality, but of management.

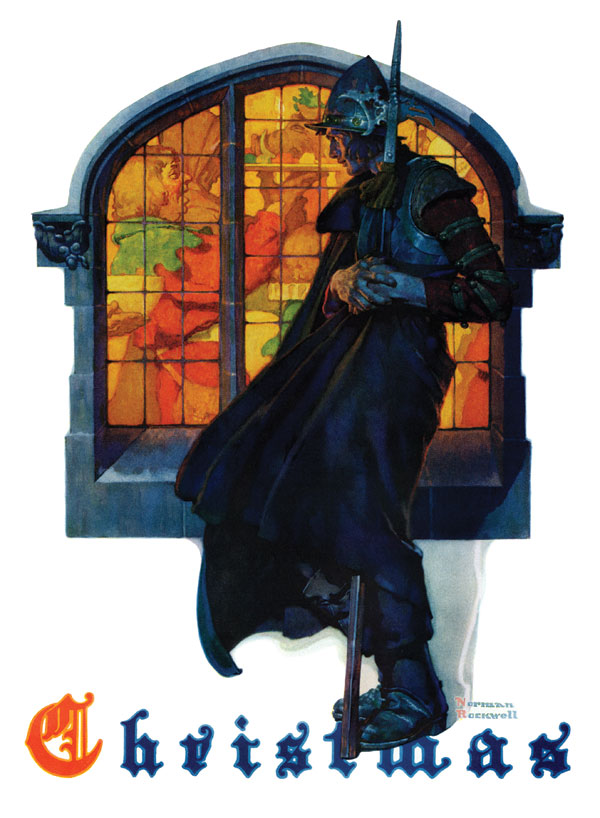

Room at the Inn

Norman Rockwell

December 6, 1930

Get this framed at Art.com

Returning home to New York from the Philadelphia offices of The Saturday Evening Post in 1930, Norman Rockwell was a happy man. Editor George Horace Lorimer had OK’d the artist’s sketch for the December 6, 1930, Christmas cover.

Lorimer’s initials “GHL” gave the artist the green light to assemble models and start the painting as soon as he arrived back in his studio. The illustration was to feature the word “Christmas” below two 16th-century guards breaking protocol by dancing in the snow while observing indoor festivities at a roadside inn.

But as Norman positioned props and began the project, he noticed that his two models—Walter Botts and Rockwell’s ex-brother-in-law and close friend, Howard O’Connor—weren’t enthused about the idea. Truth be told, Rockwell’s own passion for the project was also waning.

With the Great Depression now in its 10th month, American citizens were struggling. The revelry in the proposed scene seemed wrong. Rockwell decided to change the idea, and he invited his models and his wife Mary to speak up. Mary underscored how inspirational her husband’s covers were to American families all across the country, how it was his responsibility to lift them up in hard times. Then Walter chimed in with the story of his parents’ hospitality. They were innkeepers in Sullivan, Indiana, providing shelter and food to homeless job-seekers.

That story triggered an idea. Walter would pose as this lone, cold, 16th-century guard standing outside a roadside inn, peering through a depressed arch window at those celebrating the Christmas season. The focus shifted perspective from the haves to the have-nots. When the message reached Lorimer, he quickly approved the change.

Editor’s note: We’ve gathered 114 spectacular Christmas illustrations by Rockwell and other beloved artists from The Saturday Evening Post in a special 128-page holiday edition of the magazine on sale now!

The Art of the Post

When it came to The Saturday Evening Post, George Horace Lorimer had it covered. The legendary editor-in-chief gave the Post its first cover in 1899, and hand-picked every one thereafter for the next 30 years. Some ideas came from editors, and occasionally even readers wrote in with suggestions that made it to the cover. Mostly, though, it was the artists of the day who presented their ideas to Lorimer, in sketches and fully rendered paintings. It was a moment of mingled excitement and terror as Lorimer, “the Boss,” lined up cover prospects along a wall, then rapidly accepted or rejected illustrations with the flick of a finger. His word was final, but his judgment was unerring, as you’ll see in this gallery of Post covers.

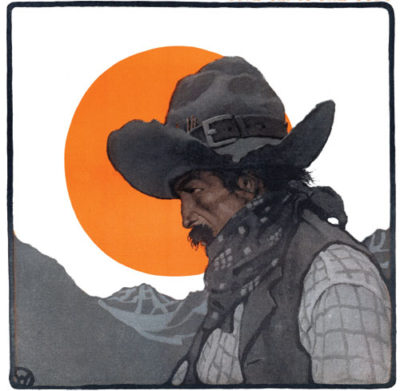

N. C. Wyeth

November 30, 1997

N. C. Wyeth

The father of painter Andrew Wyeth and grandfather of present-day artist Jamie Wyeth, Newell Convers Wyeth was a student of Howard Pyle and the Brandywine School of art. Wyeth’s first professional work was a commissioned illustration for the Post. His sense of color and mood was particularly suited to Western subjects, which also appealed to Lorimer. So the Post sent Wyeth to gain firsthand knowledge of his subject. On trips to the western United States, he worked as a ranch hand in Colorado and rode mail routes in New Mexico and Arizona.

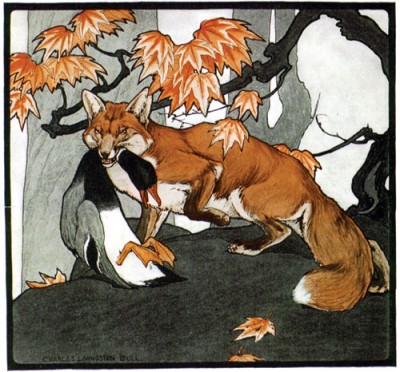

Charles Livingston Bull

Charles Livingston Bull

September 9, 1905

Known chiefly as an animal illustrator, Bull literally drew from his experience as a taxidermist at the National Museum in Washington, D.C. Bull’s images, whether an eagle soaring in flight or a fox on the prowl, gave a majestic, even startling, life and grace to his wild subjects.

Angus MacDonall

October 8, 1921

MacDonall, who came from the Midwest but eventually migrated east to become part of the Westport, Connecticut art colony, did only a few covers for the Post, but they were memorable, especially his poignant depictions of children. The forlorn boy and his dog were real, seen by a reader in Oregon, who described the scene vividly in a letter to the editor.

Ellen Pyle

Ellen Pyle

August 12, 1922

Like N.C. Wyeth, Ellen Bernard Thompson Pyle was a student of Howard Pyle’s Brandywine School, later marrying Howard’s brother Walter. When they started a family, Pyle set painting aside, but after Walter’s death in 1919, as a widow with four children, Pyle resumed her career to make ends meet. She struggled at first, but then her sister-in-law took three of Pyle’s paintings to the Post—and Lorimer promptly bought two of them, in addition to the girl with the ice cream cone, which became a cover in 1922 (after Lorimer insisted that the dog, originally shown drooling, be retouched). Pyle painted 40 Post covers in all, often using her children as models. The girls sipping sodas here are Pyle’s daughters.

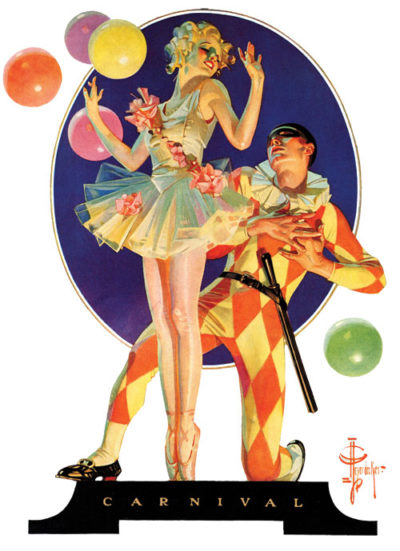

J. C. Leyendecker

J. C. Leyendecker

February 25, 1933

Joseph Christian Leyendecker received his first commission to paint a Post cover the same year George Horace Lorimer began running them, in 1899. Before Norman Rockwell arrived, no other artist had been so closely identified with the Post. Leyendecker famously created the iconic New Year’s Baby and the pudgy red-garbed rendition of Santa Claus, among other enduring images. Rockwell himself idolized the artist, calling him “a superb draftsman and a fine colorist,” as evidenced here. Leyendecker had an eye for the humor in everyday life, too (as in the case of the ample bathing beauty and her water wings, witnessed by a Post editor, who later described her to Leyendecker), which always delighted readers.

For more cover art, visit saturdayeveningpostcovers.com.

How to Raise Your Magazine Circulation by 62500% in Five Years

No magazine is immortal. Even Life came to an end.

But The Saturday Evening Post keeps going. This year we will celebrate 189 years of publication—a remarkable survival in the magazine world. But even if we had been publishing for twice as long, we still wouldn’t have any advantage going into the future.

While we study ways to continue the Post into the future, we can’t help looking back wistfully to our Golden Era, when two men created a publishing empire.

One of the men was Cyrus Curtis, who purchased The Saturday Evening Post for $1,000 in 1897 (about $26,000 in 2009 dollars). It was not a lot of money, but then, the Post of that day was not much of a publication. “The magazine’s circulation was 1,600 copies. There was one-eighth of a column of advertising in its 16 pages without cover.

“Cyrus H. K. Curtis had bought the weekly for its name alone. His was the conception of a national weekly magazine to sell at five centers. The unanimous judgment of the trade was the weekly was a dying form, the price [an 1898 nickel equals $1.28 in today’s money] an economic absurdity.” (1)

George Horace Lorimer was the other great man. Under his editorship of 38 years, the Post‘s circulation grew from 1,600 to 3 million. (Circulation passed the 6 million mark in 1960.) In a 1937 editorial, the Post editors claimed Lorimer had “brought the Post from the status of an inferior country weekly to the greatest magazine on earth in prestige, circulation, and revenue.” (1)

Naturally, today’s Post‘s editors are interested in rediscovering Lorimer’s secret for growing readership.

Part of his success can be attributed to his ambition. In an early edition, Lorimer said of the Post, “It promises twice as much as any other magazine and it will try to give twice as much as it promises.”

According to Lorimer’s biographer:

“He worked day and night that first year, and in spite of a comparatively munificent salary—forty dollars a week—he was so poor that he often had no more dinner than the free lunch that went with a glass of beer in a saloon… At the office, in spite of the growing list of distinguished contributors, Lorimer sometimes virtually wrote an issue himself.” (2)

Another key to his success, according to a biographer, was Lorimer’s faith in his own vision.

“Lorimer knew exactly what he wanted to make of the Post. It was to be a magazine without class, clique or sectional editing, but intended for every adult in America’ seventy-five million population. He meant to edit it for the whole United States. Wesley Stout wrote later, “He set out to interpret America to itself, always readably, but constructively.” (2)

A 1953 history of the Post elaborated on this vision.

“[Lorimer had a] perception which knew what the reader wished to read before the reader knew it, an intuition which needed no questionnaires to guide it.

“The first necessity of a magazine is to be interesting; unless it is read eagerly, it is futile. But it was no mere magazine of entertainment that he edited… Entertainment attracts readers, but only character gets their respect and affection.” (3)

To give his magazine a broader American flavor, Lorimer developed a new, national tone—one that avoided the East-Coast flavor of most magazines.

“Lorimer perceived why American magazines were so much alike. The same authors rotated through the better publications. Editors and writers alike copied each other, sometimes quite shamelessly, and since most of the magazines were edited in New York, they had come to have a parochial point of view… Lorimer eliminated much of this difficulty at one stroke by refusing to look at another magazine.” (2)

Another Lorimer innovation was the higher graphic content of the Post. Starting in 1899, the Post reserved its covers for full-page illustrations. The first illustrated cover appeared on September 2, 1899, and showed the two great racing yachts, Columbia and Shamrock, as they were expected to look in the impending American Cup races.

Lorimer also aggressively pursued the best writers of the day.

“The Post revolutionized free-lance writing by giving decisions in 24 to 72 hours and paying on the first Tuesday following acceptance. Thus its free-lance contributors received their due in a week or so instead of a year, and sometimes were paid within as little as three days.

“Though it placed a heavy burden upon the editors, the new system got results instantly. Free-lance contributors over the nation and the world made a habit of turning first to the Post.” 3

Thus the Post offered works from highly popular writers like the still-remembered Bret Harte, Rudyard Kipling, Booth Tarkington, Joseph Conrad, and O. Henry, as well as the now-obscure Joel Chandler Harris, Richard Harding Davis, Rupert Hughes, Marie Corelli, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Opie Read, Joseph Lincoln, and Brand Whitlock.

“There was but one dish missing in the Post menu that Lorimer planned to serve his readers, and that was business fiction. To him business was a wonderful, romantic adventure. He could chronicle it in articles by and about businessmen, but he was certain that it could also be done in fiction.

“He had a strong feeling that this was the kind of writing which would give Post circulation an even faster upward swing. It had passed the 250,000 mark by the end of 1900, and no one doubted it would soon reach 500,000.

“Lorimer could not interest any writer in the business story. In vain he pointed out that ‘the struggle for existence is the loaf, lover or sex is the frosting in the cake,’ and that every business day was full of comedy, tragedy, farce, romance — all the ingredients of successful fiction. Business was a dominating factor in the lives of Americans, but the nation’s writers ignored it.” (2)

Lorimer’s fascination with the American businessman was in harmony with the national admiration for its wealth-builders and quick-witted entrepreneurs. Impatient to explore this new literary niche, Lorimer began writing an unsigned series of articles for the Post, entitled “Letters from a Self-Made Merchant to His Son.” They quickly built an enthusiastic following, and Post subscriptions jumped. The drama of business was, itself, good business.

In 1929, though, the romance of the American marketplace collided with reality. Through the months and years following the great stock market crash, the American public grew disenchanted with its corporate culture and melodramatic tales of boy-meets-business romances.

According to Otto Friedrich, a former Post editor, Lorimer never reconciled his vision of the American Dream to the realities outside his windows. He worked tirelessly, taking on more and more of the responsibility for managing the magazine—proofreading copy, writing ads, researching articles, and eventually becoming the chairman of the board at Curtis Publishing. In his world, American culture equaled American business, which could always be relied on to solve the nation’s ills and oppose new ideas and new people.

“It was perhaps this incredible involvement in his job, and not just his native conservatism, that made Lorimer become so remote from his readers and his people. An admirer of Hoover, he wrote to a friend, “I’ll fight this New Deal if it’s the last thing I do.” He called it “a discredited European ideology”; he railed against “undesirable and unassimilable aliens”; and the Post declared: “We might just as well say that the world failed as the American business leadership failed.” The election of 1936 was a humiliating blow, which, according to one chronicler, left Lorimer ‘crushed, bewildered, a stranger in a land he loved.'” (4)

Most of Lorimer’s principles—work, innovation, and better content—will still build readership. But given the state of our current economy, the unemployment rate, and the large number of Americans who worry, with good reason, about their job security, now may not be a good time to revive the genre of business fiction.

We could be wrong, though. Maybe the time has never been better for the Great American Business Novel.

This week, we include one of the business stories written by Sinclair Lewis for the Post. Lewis never shared Lorimer’s admiration of businessmen. In his novels Babbitt and Main Street, he wrote hilarious and deadly critiques of America’s commercialized culture. But Lewis never lost a deep-seated admiration for the men and women in American companies who made the country so prosperous and strong.

1 Au Revoir, But Not Good-By, The Saturday Evening Post, January 2, 1937

2 George Horace Lorimer and the Saturday Evening Post: The Biography of a Great Editor; John Tebbel, Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1948

3 A Short History of the Saturday Evening Post, Curtis Publishing Company, 1953

4 Decline and Fall: The Struggle for Power at a Great American Magazine; Otto Friedrich, Harper & Row, 1969