College of Dreams: Creating a Bright Future for ALL Students

Where Princeton Nelson came from, a college education wasn’t just at the outer edges of possibility, it was beyond imagination. Yet here he was, a proud member of the class of 2018 at Georgia State University, a computer science major with a cap and gown and a more than respectable 3.3 GPA, taking his place at a crowded indoor commencement ceremony along with the Atlanta Fife Band and professors in gowns of many colors and a cascade of balloons in Panther blue and white that tumbled from the ceiling like confetti.

He, too, got to shake hands with the university president, Mark Becker, whose welcoming remarks had invoked “the magical power of thinking big.” He, too, got to hug his fellow graduates, many of them seven or eight years younger than him. He, too, could bask in the pride of his relatives, none more amazed or delighted than the grandmother who had thrown him out as a teenager because he’d been too unruly to handle.

Princeton Nelson came from nothing, and he understood at an early age that it would be up to him to carve a path to something better.

Nelson came from nothing, and he understood at an early age that it would be up to him to carve a path to something better, because nobody else was going to do it for him. Even when he slipped — and he slipped a lot — he knew the choices he made could mean the difference between life and death. He was born in an Iowa prison, the child of two parents convicted of drug dealing at the height of the crack cocaine epidemic.

Mostly, he was raised by his grandmother, Loretta, who did her best to raise Nelson and three siblings on an assembly worker’s salary in a small red house in suburban Chicago. Nelson’s mother was in no state to take him even when she got out of prison. She fell back into the drug underworld and, months after her release, was found shot to death in an abandoned building on Chicago’s South Side.

Loretta moved Princeton and his siblings to Atlanta for a fresh start, but there was little she could do to make up for what he had lost — or never had. By sixth grade, he was attending an institution for children with severe emotional and behavioral problems. His grades yo-yoed, he bounced in and out of special schools, and he barely graduated from high school.

Turning himself around was a long and painful process. For years, he worked in warehouses and smoked weed and gave little thought to where his life was going. Still, he hated the feeling that he was a disappointment to his grandmother. He signed himself up at Atlanta Technical College, thinking at first that he’d train to be a barber. Then it dawned on him that as long as he was taking out loans he’d be better off working toward an academic degree, not just a trade qualification. As it happened, there was a community college, Atlanta Metropolitan, right across the street, and he wandered over one day to enroll as a music major. He’d always enjoyed creating music beats on his grandmother’s computer. Why not see where it could take him?

As he stood in line to register, he noticed a chart listing the professional fields expected to be most in demand in the Atlanta area by 2020, and his eyes fell on the words “computer science.” “What did I have next to me in my grandmother’s house this whole time?” he said. “A computer!” It wasn’t just music beats that he’d created. He’d also worked on MySpace pages and video games, never thinking there could be a future in it. But now, apparently, there was. “It was a flash of light,” he said, “I’m thinking, I’m a computer science major. That’s my calling.”

Nelson’s grades were strong enough to earn him an associate’s degree in computer science in two years. But his life, like that of almost every lower-income college student, remained precarious at best, a constant battle for time and money. When his aunt and uncle bought the house where he and his grandmother were living, one of the first things they did was evict him, saying they were concerned about his pot use and the shortcuts they suspected he was taking to make ends meet. Before he could think of pursuing his studies further, he had to deal with the realities of homelessness. For two weeks he slept on the concrete floor of a bus station so he could bump up his savings from a job flipping burgers and buy himself a car. Once he had his Volkswagen Jetta, he signed on as an Uber driver. Soon he had a third job, as a security guard. Three days a week he stayed in a hotel to enjoy a bed and a hot shower; the other four days he parked overnight at a 24-hour gas station or outside a Kroger’s supermarket where the lights and security cameras made it less likely he’d be robbed, or worse.

He was still homeless when he started at Georgia State in the fall of 2016, but starting in his second year, he joined forces with two of his fellow computer science majors and started designing websites as a side gig. That made him hopeful enough to move out of his car and put all his savings into a deposit for an apartment. It was touch and go at first, because the freelance design work didn’t come in as quickly as hoped, and he had to take a full-time job as a cellphone technician for two weeks to make what he needed for the next month’s rent.

To many eyes, Nelson might not have looked like college material at all. Georgia State, though, was starting to enjoy a national reputation for its pioneering work in retaining and graduating large numbers of students much like him — poor, Black, and struggling to make it as the first in their family to attend college. The university understood his need for extra support. When it became apparent he was depressed because of the financial pressures, he was encouraged to see a campus therapist, the first counselor he’d ever talked to. Twice when his money was running dangerously low, the university awarded him grants to help him reach the finish line.

Academics were never Nelson’s problem. Next to what he’d been through, a challenging course in math or programming held no terrors. Rather, he became fascinated by what it meant to live a normal, middle-class life and was determined to learn how to lead one himself. “I’m always thinking about where I came from. And I still feel like I’m dumb, like I’m still competing with all these college students and falling short.”

While the children of the rich and the very rich continue to enjoy expanding opportunities to pursue a university education, the prospects for everyone else have either stagnated or narrowed dramatically.

It’s a feeling that did not go away even after he graduated and headed toward his first full-time job as a software engineer for Infosys. “That’s the difference between me and those Harvard kids,” he said. “If people like me fail, we’re going to fail our life.”

Nelson was far from the only member of Georgia State’s class of 2018 with a tale of adversity and triumph. Greyson Walldorff, who had been forced to give up an athletic scholarship in his sophomore year because of a concussion, stayed afloat and completed a business degree by starting a landscaping company that grew over time to five employees and more than a hundred clients. Larry Felton Johnson completed a journalism degree on his fourth try, 49 years after he first enrolled, thanks to a state program that offered free tuition to students over the age of 62.

Then there was Savannah Torrance, who had almost dropped out in her freshman year because she was commuting 60 miles each way from her mother’s house, working long shifts at a supermarket, and absolutely hating the chemistry class she thought she needed to build a career in the medical field. Thanks to some timely guidance from Georgia State’s advising center, though, she switched to speech communications, which required no chemistry, won a state merit scholarship she’d narrowly missed out of high school, and was soon thriving both in her studies and as a student orientation leader, university ambassador, and member of the student government association.

Georgia State boasts almost no success story that doesn’t include at least one moment where everything was in danger of crumbling to dust. At a school where close to 60 percent of undergraduates are poor enough to qualify for the federal Pell grant, that is just the nature of things. What is remarkable about Georgia State students is that despite the precariousness of many of their lives, they still graduate in extraordinary numbers. In 2018, more than 7,000 crossed the commencement stage, 5,000 of them to pick up a bachelor’s degree and the rest an associate’s degree from one of the university’s five community college campuses scattered around the Atlanta suburbs. That translated to a six-year graduation rate of close to 60 percent, significantly above the national average.

Georgia State’s achieved a 74 percent increase in the graduation rate over 15 years. This is not just about the lives of a few unusually tenacious and talented individuals. We are talking about a fundamental transformation, a real-time experiment in social mobility that the university has learned to perform consistently, and at scale.

How did Georgia State do it? In the wake of the 2008 recession, a new leadership team at Georgia State, acting out of economic necessity as well as moral conviction, determined that there was nothing inevitable about the failure of students who were poor, or nonwhite, or whose parents had never attended college. Rather, what held them back were barriers erected by the university itself and by the broader academic culture. Georgia State developed data to understand those barriers and to identify the inflection points where students most commonly came to a crossroads between success and failure. For years, Georgia State has graduated more African Americans than any other university in the country — not by tailoring special programs to them but by treating them like everyone else and providing support where they need it, regardless of wealth, or skin color, or any other consideration.

While the children of the rich and the very rich continue to enjoy expanding opportunities to pursue a university education, the prospects for everyone else have either stagnated or narrowed dramatically.

Once, student success was thought to be a simple combination of academic promise and hard work. Now even the pretense of that egalitarianism is gone; it’s all about money and whether your parents went to college. A study by the National Center for Education Statistics from 2000 — when things were better than they have become — found that a student in the top income quartile with at least one college-educated parent had a 68 percent chance of graduating before the age of 26, whereas a student in the bottom quartile whose parents did not go to college had a 9 percent chance.

It’s not that these staggering problems have gone unnoticed. Mostly, institutions have been at a loss to address them. Many prefer to keep their focus elsewhere — on graduate programs, on research, or on cultivating an elite class of undergraduates from that golden upper quartile. Some like to point fingers: at the shortcomings of the K–12 education system, at budget-cutting state legislatures, at a political culture that loves to hate academia and questions why students don’t invest in their own futures instead of relying on the public purse for financial aid. It has become fashionable for elite institutions to brag about the lower-income students they champion and finance, but they do this at a scale entirely dwarfed by a public university like Georgia State, which has three times as many Pell-eligible students as the entire Ivy League.

It has taken more than 20 years to come up with a more durable answer to the problem and to push back against a higher education culture that too often serves the interests of everyone but the students. The first stirrings came at a handful of public universities in Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Arizona — states with rapidly growing urban populations and a hunger for economic growth that exceeded any appetite to hold back historically suppressed racial minorities. Why, administrators in these states started asking, should faculty members get to decide when to teach classes if it means students have to wait extra semesters to take courses essential to their majors? Why should students with no family history of negotiating an undergraduate degree have to figure out for themselves which classes to take, in which order?

Starting in the mid-1990s, these campuses rewrote course maps, rethought student advising, grouped freshmen together by subject area, lifted registration holds for petty library fines, and found a variety of other ways to ease the students’ path through the campus bureaucracy.

After 2008, Georgia State was able to take these ideas and turbocharge them with the analytical powers of emerging new data technologies. The incoming president, Mark Becker, was a statistician by training who understood the power of creating successful models and scaling them across tens of thousands of students. His student success guru, Tim Renick, had been a singularly gifted classroom teacher and needed no persuading that lower-income and first-generation students were worth believing in, because he’d seen over and over how they responded to his teaching and thrived.

Renick couldn’t stomach a system that knowingly sold students a bill of goods, inducing them to load themselves up with debt for a degree that at least half of them stood no chance of getting. What started as a moral imperative to graduate large numbers of traditionally underserved students has become a national rallying cry, a challenge to other institutions to ditch the old excuses and follow Georgia State’s lead.

The wonder of Georgia State rests on a simple idea: that if students are good enough to be admitted, they deserve an environment in which they can nurture their talents regardless of personal circumstances.

Georgia State’s pioneering innovations have been written up in The New York Times and discussed with fervor at hundreds of education conferences. Public universities nationally are in broad agreement that the revolution in downtown Atlanta points the way to all their futures. These breakthroughs came about thanks to the interactions of those educators who threw themselves into the work and stuck with it despite long hours and modest compensation, because they couldn’t imagine doing anything more meaningful with their lives; and of course the role played by the students, whose tenacious example and unbreakable will either inspired important changes or exemplified their life-changing benefits or, often, a bit of both.

Andrew Gumbel worked as a foreign correspondent for Reuters and the British newspapers The Guardian and The Independent. He is the author of Down for the Count, Oklahoma City, and Won’t Lose This Dream.

Copyright © 2020 by Andrew Gumbel. This excerpt originally appeared in Won’t Lose This Dream: How an Upstart Urban University Rewrote the Rules of a Broken System, published by The New Press. Reprinted here with permission.

This article is featured in the November/December 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

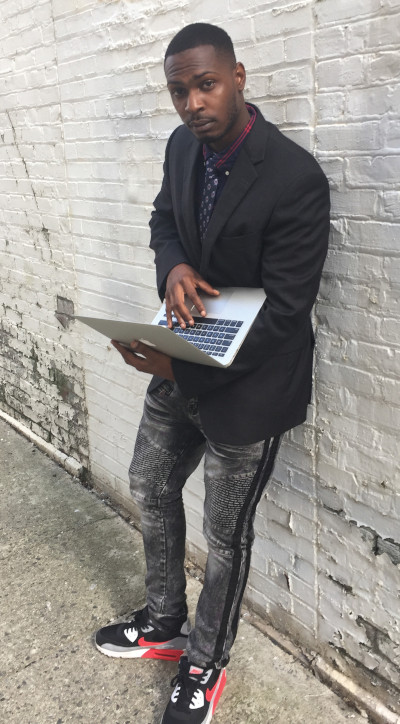

Featured image: The future looks bright: GSU has gained a reputation for graduating large numbers of students who are poor, Black, and struggling. (Steve Thackston/staff photographer at Georgia State University)