The Art of the Post: The Saddest Cover

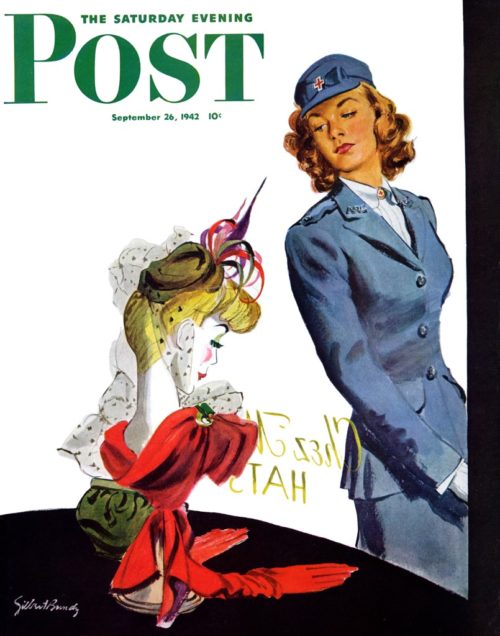

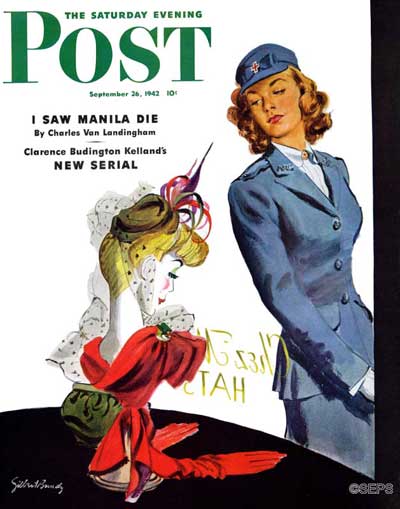

My candidate for the saddest cover of the Post is this painting by Gilbert Bundy of a WAC looking over her shoulder at a frivolous hat in a store window.

The determined WAC is headed off to do her duty. Her thoughtful expression suggests she’s a little wistful about the pretty things she is leaving behind. But what makes that so tragic?

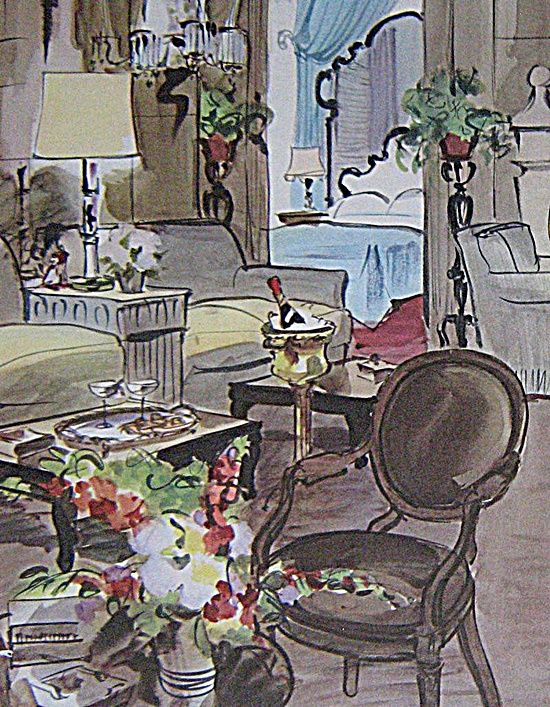

The artist, Gilbert Bundy, earned fame in the 1930s for his light-hearted watercolor cartoons of beautiful women in high society scenes.

He seemed to take particular pleasure in painting floral arrangements:

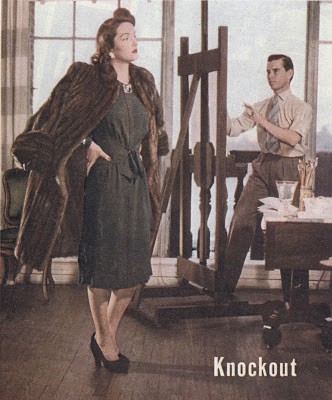

Photos from the social pages of the time show the handsome young illustrator at parties, dressed in his tuxedo and escorting lovely young socialites. Here we see him in his studio painting one of his elegant models:

His charmed life continued as he fell in love, married, and had a baby daughter. The future looked good.

But when World War II began, the stakes changed. We can’t know exactly what was going through Bundy’s mind as he painted that cover for the Post. All we know is that, like the WAC in his painting, Bundy decided to abandon his civilian life painting pretty girls and go to war. He volunteered to work as a war artist covering the South Pacific for Hearst newspapers.

In 1944, Bundy was participating in the Marine invasion of the island of Tarawa when a Japanese shell exploded in his small landing craft. Bundy awoke to find himself trapped beneath the bodies of four Marines. The wreckage of the craft had drifted onto a coral reef within range of enemy gunners on the island. For most of that long day, Bundy remained pinned beneath corpses and drenched with blood, as enemy bullets and shells strafed the remnants of the craft. When night came, Bundy managed to free himself and swam away from the wreck, taking his chances spending a night alone in shark infested waters rather than endure another day under enemy fire.

The Hearst newspaper reported, “He was believed dead for three days. His reappearance startled his Marine mates.”

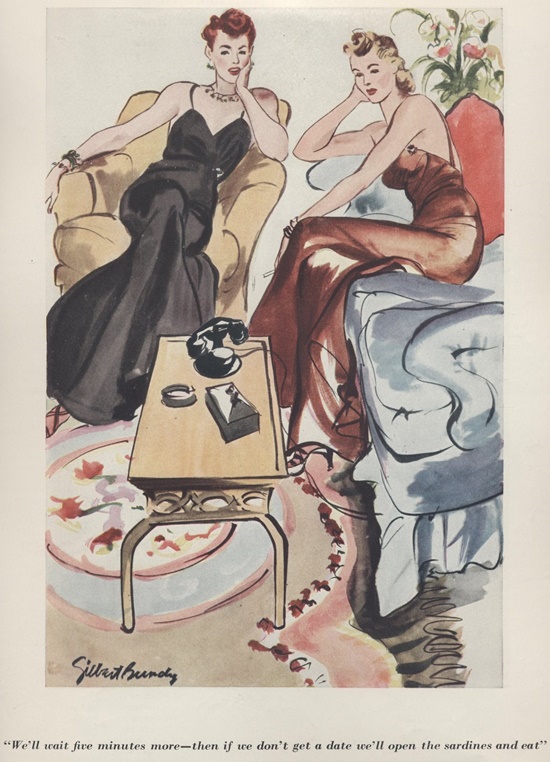

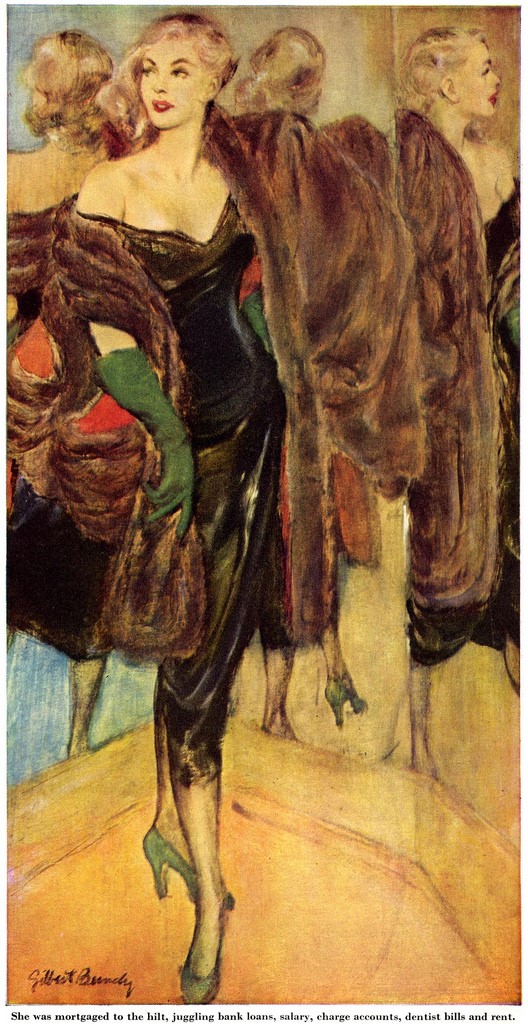

Bundy was shipped back to the U.S. where he tried to return to his previous life. He painted a series of illustrations of light-hearted romantic stories for the Post.

For the story, “Good Time Girl” by Lester Atwell, which appeared in the Post on January 31, 1948, Bundy painted a woman in a fur coat standing in front of a three-way mirror. After a couple of unsatisfactory attempts, he decided to paint the woman three times: “I finally posed my model backward or sidewise in three separate poses, one for each panel of the mirror, and worked direct. Then I combined the three to get the triple-reflection effect.”

His challenge, Bundy reported, was painting a pair of beautiful legs from three different angles. Who could ask for a more fun job?

But beneath the surface Bundy remained haunted by his wartime experience.

On the anniversary of his ordeal, Bundy committed suicide and rejoined his fallen comrades.

In hindsight, his Post cover about the WAC has a tragic air. The WAC was taking a last lingering look at civilian pleasures as she responded to the call of duty. Whatever was going through Bundy’s mind as he painted, he couldn’t know what horrors lay in store for him. His refined fingers, so well suited for painting delicate pictures of flowers and shapely girls, were not well suited for clawing their way out from under corpses.

Comparing his illustrations before and after the war, we see that his art lost much of its confidence and certainty. Gone was the joyful exuberance. His deft brush strokes became labored and heavy handed. His pictures—like his life—seemed to lose their balance and proportion.

If you or a loved one is struggling with thoughts of suicide, you’re not alone. Call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

A Salute to Veterans

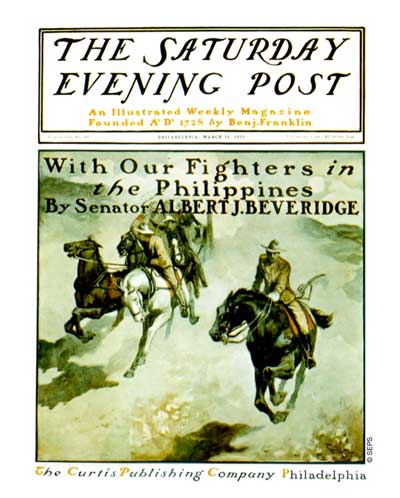

Tributes to the military have long been portrayed on covers of The Saturday Evening Post, from situations serious to humorous. In honor of Veterans Day, we would like to share some of our favorites.

The first Post military cover? An action depiction of U.S. soldiers on horseback in the Philippines.

George Gibbs

March 31, 1900

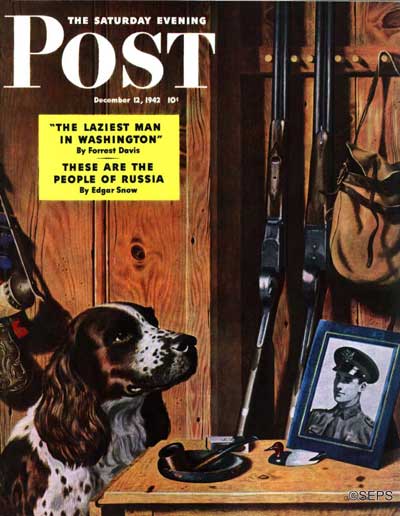

He’s in the Army now. A seldom seen cover from December 1942 by John Atherton shows a faithful dog and a photo. From the uniform, we can guess where its master is. We hope he returns home soon – Spot is itching to go hunting.

John Atherton

December 12, 1942

The enlisted also included members of the Women’s Army Corps (WAC), as shown in the cover from 1942 by an artist named Gilbert Bundy.

Gilbert Bundy

September 26, 1942

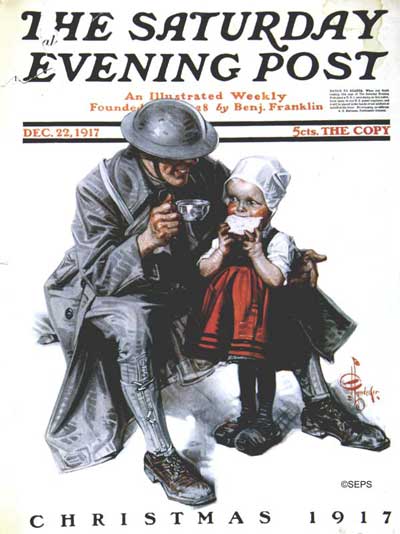

A WWI soldier shares a humble Christmas meal in this endearing 1917 cover by the prolific J.C. Leyendecker.

J. C. Leyendecker

December 22, 1917

On the May 14, 1927, cover by E.M. Jackson, this sailor accomplishes an important mission overseas — finding a genuine American hot dog!

E.M. Jackson

May 14, 1927

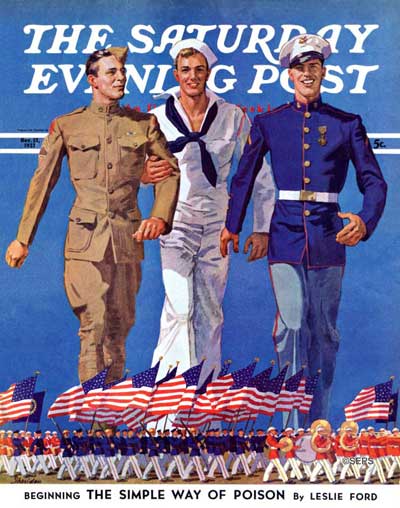

Celebrating soldiers, sailors, and marines, the 1937 cover by John Sheridan captures all three with a parade below in their honor.

John Sheridan

November 13, 1937

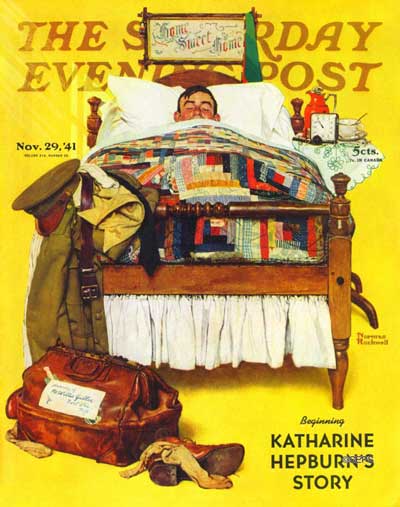

Norman Rockwell honored the military during the WWII years with several covers of the “every soldier” he named Willie Gillis. We’ve shown Willie’s military adventures before, but not this one from 1941. Rockwell’s famous private is home on leave, snuggled under the quilts and enjoying the luxury of sleeping late. The sign above the bed echoes our ardent wish for all our military men and women: Home Sweet Home.

Norman Rockwell

November 29, 1941

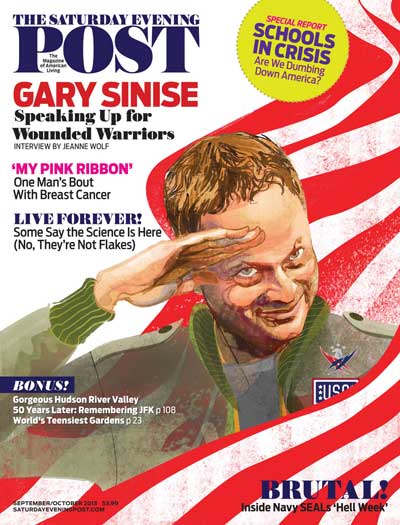

After Forest Gump, actor Gary Sinise became an advocate for wounded soldiers. Check out Jeanne Wolf’s interview with Sinise from the September/October 2014 issue here.

John Jay Cabuay

September/October 2014

Classic Art: Great Illustrators from Past Issues

Although The Saturday Evening Post is famous for its covers, some of the most striking art has been hidden inside the magazine.

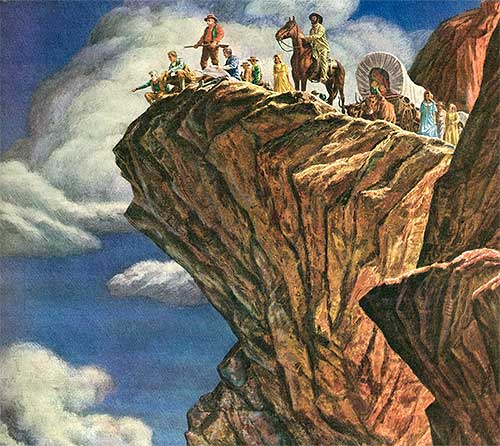

“Squaw Fever,” art by Paul Rabut

by Paul Rabut

From April 26, 1947

This dramatic painting by Paul Rabut appeared in the 1947 story “Squaw Fever” by Bill Gulick. The caption reads: “All you got to do is put wings on your wagons an’ fly ’em into the valley. Ain’t that right, captain?” Illustrations like this make us wonder where the original paintings ended up.

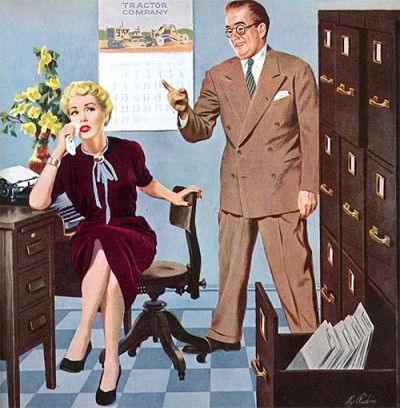

“Love and Alexander Botts,” art by Hy Rubin

by William Hazlett Upson

From March 14, 1953

“Only desperate measures, he saw, could keep this girl from marrying the wrong man. It was a challenge the greatest of salesmen couldn’t resist.”

I don’t remember the Alexander Botts stories in the Post, but I’ve heard from many readers who do. The hardworking salesman for the Earthworm Tractor Company was created by William Hazlett Upson, and readers couldn’t wait for his next adventure. This 1953 Hy Rubin illustration is captioned: “‘For every problem there is always a solution,’ (Botts) said. ‘I will start now looking for it.’”

It would be a bit irritating to have a boss that darned cheerful while one is nursing a broken heart, but that’s Botts for you.

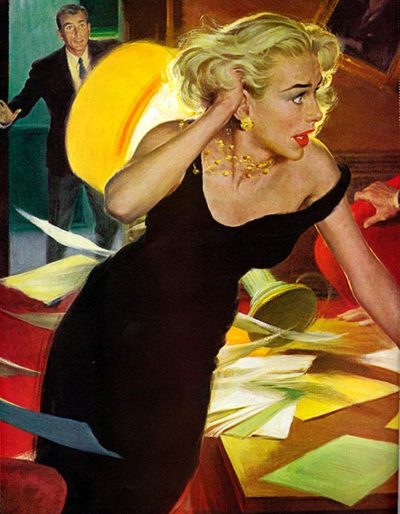

“The Cold-War Blonde,” art by Robert G. Harris

by Robert G. Harris bore

From September 26, 1959

It’s never good when there’s a Cold War raging, you’re rifling through a desk, and you get caught by the Russians–as this unfortunate young lady from the 1959 story “The Cold-War Blonde” by George Fielding Eliot did.

“She risked her honor for her country, and her methods were most unusual…” Whatever that means. The luscious artwork by Robert G. Harris bore the caption: “On the other side of the desk, ready to vault over it, crouched Zaspurov.” Can’t get anything by a danged Commie.

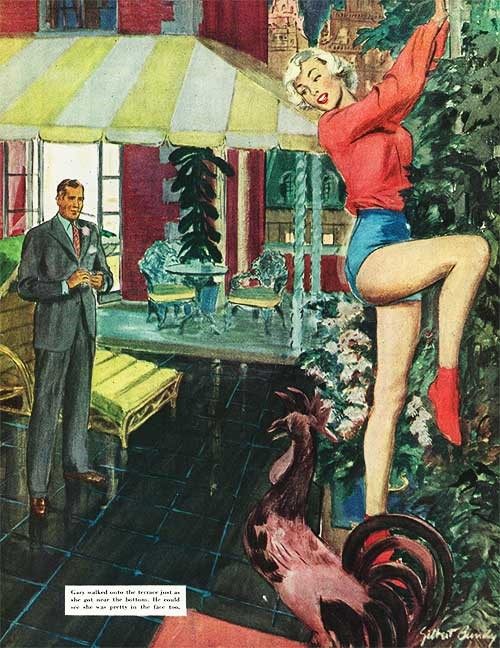

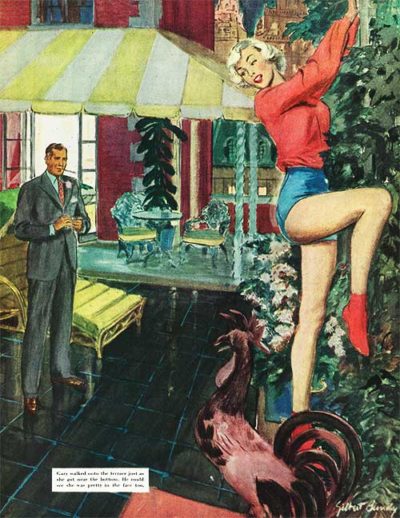

“Escapade,” art by Gilbert Bundy

by Gilbert Bundy

From April 30, 1949

“Gary walked onto the terrace just as she got near the bottom. He could see she was pretty in the face too.”

Too? Apparently she was pretty from, er, other angles. How did people get themselves into these situations? Something about … she threw a boot at the house detective and it went over the terrace … or something. She is rather brazen, as we’ll see below.

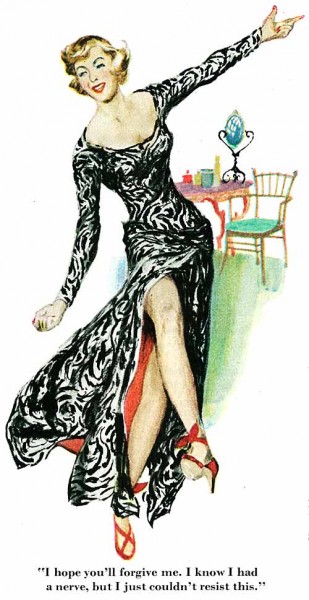

“Escapade,” art by Gilbert Bundy

by Gilbert Bundy

From April 30, 1949

“He was trapped in his fiancee’s apartment with a strange girl wearing his fiancee’s gown. Could you talk your way out of that?”

Well, I’d love to hear him try. It seems the young lady made herself at home. “I hope you’ll forgive me. I know I had a nerve, but I just couldn’t resist this,” reads the caption of her trying on the gown. Uh, yeah, nervy would be one word for you, toots.

Beware of young ladies who climb over your terrace. This was from a 1949 story called “Escapade” by George Marion Jr.

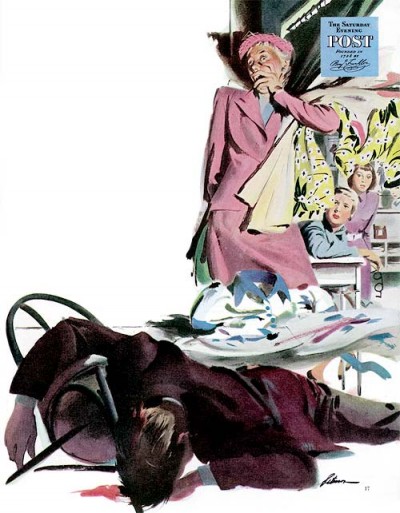

“Stolen Goods,” art by Perry Peterson

by Perry Peterson

From June 11, 1949

“She stared into the ladies’ dressing room and tried not to faint. It was terrifying to find a man in there—especially when he was dead.”

If three-way mirrors aren’t enough to put you off clothes shopping, this should do it. This is from a 1949 serial called “Stolen Goods” by Clarence Budington Kelland. The artwork was by Perry Peterson.

More inside illustrations to come!