Songs of America: Patriotism, Protest, and the Music That Made a Nation

The city was thronged. On Thursday, September 3, 1936, tens of thousands of people lined the streets of Des Moines, Iowa, to catch a glimpse of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who arrived by train at the Rock Island station at noon. Troops from the Fourteenth Cavalry stood at attention as uniformed buglers greeted the commander in chief, who emerged from Pioneer, his private carriage, balanced on the arm of his youngest son, John Roosevelt, smiling broadly and waving to a cheering crowd.

Nearly half a century later, at least one admirer could recall the day in great detail. A young sportscaster at Des Moines’s WHO radio station had been visibly thrilled as he hurried to the window of his offices on Walnut Street to take in the motorcade. “Franklin Roosevelt was the first president I ever saw,” Ronald Reagan told a gathering of Roosevelt family and New Dealers at a 1982 centennial celebration of the 32nd president’s birth.

Speaking in the East Room, Reagan, now the 40th president, paid tribute to the Democrat for whom he had voted four times — in 1932, 1936, 1940, and 1944. “Like Franklin Roosevelt, we know that for free men hope will always be a stronger force than fear, that we only fail when we allow ourselves to be boxed in by the limitations and errors of the past.” The president then offered a toast: to “Happy days — now, again, and always.”

The reference was unmistakable, for Franklin Roosevelt and the song “Happy Days Are Here Again” were inseparable in the political imaginations of Americans. The song entered the nation’s political consciousness at the Democratic National Convention at the Chicago Stadium in 1932. Roosevelt, who was seeking the presidential nomination, had planned to have “Anchors Aweigh” as his theme song, reminding delegates and listeners on the radio of his tenure as assistant secretary of the Navy during the Great War. From his command post at the Congress Hotel, Roosevelt adviser Louis Howe listened to his secretary, a fan of “Happy Days Are Here Again,” sing it out for him. Impressed, the wizened political sent word to the hall to change course: “Happy Days Are Here Again” was now the FDR standard.

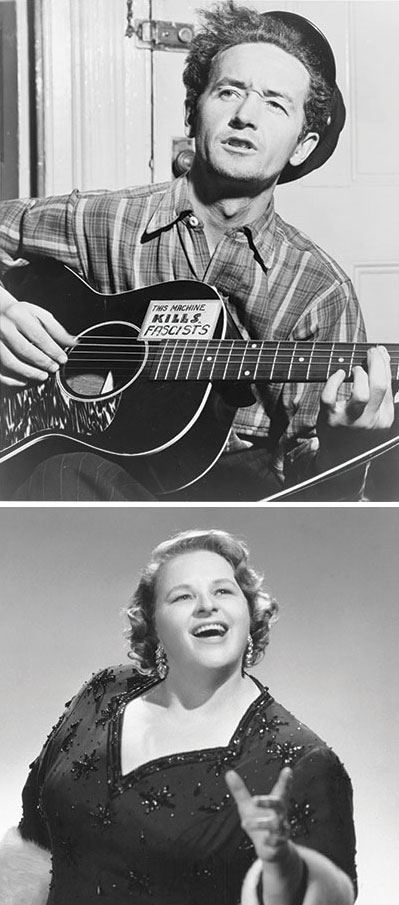

In 1938, the drift toward chaos and bloodshed in Europe prompted the composer Irving Berlin to excavate a song he’d written in 1918, “God Bless America.” He arranged for the singer Kate Smith to perform it on her CBS radio show on Armistice Day 1938, and Smith would record the number in early 1939. In the late 1930s, fearing Hitler, listeners did not have to think hard about what she meant when she spoke of “the storm clouds” gathering “far across the sea” or “the night” that required “a light from above.” Woody Guthrie, though, heard something else in Berlin’s verses: a triumphalism that portrayed America simplistically and sentimentally. And so Guthrie wrote a reply. Initially titled “God Blessed America,” it became “This Land Is Your Land,” a song that grew in popularity during and after World War II. (By 1968, Robert Kennedy was suggesting that “This Land Is Your Land” ought to be the national anthem.)

In wartime, the simpler the song, the more powerful it was, not least because life under fire was so emotionally complicated. The most moving music of the war was the music that moved the troops themselves — songs of longing and loss, of love and hope. There was “We’ll Meet Again,” “You’ll Never Know,” and big band numbers by Glenn Miller, Benny Goodman, and others. It was the age of such songs as “Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy,” and Miller and the Andrews Sisters each had a hit with “Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree (with Anyone Else but Me).” Miller, whose “Moonlight Serenade” was a signature song, lobbied to join the military once America entered the war. (Born in 1904, he was in his late 30s.) Bing Crosby wrote the government a letter of recommendation, saying that Miller was “a very high type young man, full of resourcefulness, adequately intelligent, and a suitable type to command men or assist in organization.” Commissioned in the Army Air Force, Miller set out, he said, to “put a little more spring into the feet of our marching men and a little more joy into their hearts.” Regular military bands resisted Miller’s attempts to bring the music forward from the Great War to the 1940s. “Look, Captain Miller,” one is said to have complained, “we played those Sousa marches straight in the last war and we did all right, didn’t we?”

“You certainly did, Major,” Miller replied, according to the story. “But tell me one thing: Are you still flying the same planes you flew in the last war, too?”

On a broadcast on Saturday, June 10, 1944, a few days after D-Day, he announced, “It’s been a big week for our side. Over on the beaches of Normandy our boys have fired the opening guns of the long-awaited drive to liberate the world.” The band’s opener that day was “Flying Home,” a jazz number by Lionel Hampton (Ella Fitzgerald would later sing a powerful version) that, for African-American GIs, signified a journey toward the kind of freedom at home they’d been fighting for abroad.

Franklin Roosevelt died of a cerebral hemorrhage on the afternoon of Thursday, April 12, 1945, in his cottage at Warm Springs, Georgia. As the president’s body was being moved to the train for the trip to Washington, a naval chief petty officer, Graham Jackson, tears streaming down his face, played “Going Home” on his accordion.

Woody Guthrie may have offered the most timeless memorial to the fallen Roosevelt. In a song addressed to Eleanor, Guthrie remembered FDR as a providential figure:

Dear Mrs. Roosevelt, don’t hang your head and cry;

His mortal clay is laid away, but his good work fills the sky;

This world was lucky to see him born.

There is, really, nothing more to say on the matter. The world was lucky to see him born.

Jon Meacham is a Pulitzer Prize–winning biographer and author of The Soul of America (2018). Tim McGraw is a Grammy Award-winning country music artist.

From Songs of America: Patriotism, Protest, and the Music That Made a Nation by Jon Meacham & Tim McGraw, published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2019 by Merewether LLC and Tim McGraw.

This article is featured in the May/June 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo.

How the Music of the Big Bands Defined a Generation

It was cold — to be expected on a January night in New York. But the ticket holders filed into the gold and white auditorium of Carnegie Hall, but not to hear the New York Symphony or New York Philharmonic that night.

The chairs were on the stage, and the musicians came out and took their places, as did their conductor — Benny Goodman, The King of Swing. He did not have a baton. He used his hand to give the downbeat, then put the clarinet to his lips and joined in the opening number, a Benny Goodman hit, “Don’t Be That way.”

And what is considered “the single most important jazz or popular music concert in history: jazz’s ‘coming out’ party to the world of respectable music” was underway.

It was the night of January 16, 1938.

The night Jon Hancock, the man who literally wrote the book on it, summed up nicely. “That 1938 concert is the stuff of legend and is probably the most widely talked about event in the history of Carnegie Hall.”

That was due, in no small part, to the end number.

It’s always hoped one builds to a great ending in any artistic endeavor, and Benny Goodman and the musicians on the stage of Carnegie Hall that night hit it out of the park with “Sing, Sing, Sing.”

Benny Goodman playing “Sing, Sing, Sing” (uploaded to YouTube by Benny Goodman – Topics / Believe SAS)

It runs 12 minutes and 8 seconds. And if you can listen to it and not feel better, perhaps your foot tapping, your fingers snapping to the rhythm and beat, there is no hope for you musically.

The Big Band Era about to become the epicenter of modern music — the music I grew up to and listened to on the radio. In junior and senior high school, when I’d finished my homework and was ready for bed, I’d turn on the radio and tune to the station that would give me the sweet strains of the Glenn Miller theme song, “Moonlight Serenade,” the announcer telling me, in equally dulcet tones, it was coming “from the Glen Island Casino overlooking Long Island Sound.”

The Big Bands became so popular they not only played nightspots from which they broadcast, they were booked for proms at colleges and dances at hotels, toured movie theaters to be the stage show for that week (or next), and were featured in movies. Some, like Kay Kyser, the “Ole Professor of the Kollege of Musical Knowledge,” had weekly radio shows.

Part of my teen years were spent in record shops, in the glass-enclosed booths where my friends and I could play a record before buying it. And the records were played on the radio at all times of the day. I remember the semester I went off to high school with Wee Bonnie Baker’s recording of “Oh, Johnny, Oh!” playing on the car radio as my father drove me to school.

My sophomore year, the guy across the aisle from me in my creative writing class introduced me to the classics — Bob Crosby’s “Big Noise From Winnetka” and Will Bradley’s (it really was a record) “Celery Stalks at Midnight.”

I remember the summer evening before my junior year in high school when my parents and I were driving home after dinner at a favorite restaurant and the record that came on the car radio — the first time I heard it, the soft summer air coming in through car windows — “I’ll Never Smile Again.” The soft voice of Frank Sinatra, Tommy Dorsey’s new band singer, backed by the Pied Pipers. The song that lifted Sinatra to stardom was written by a Canadian pianist and songwriter, Ruth Lowe, after her husband died. Not in the war, which had started then for Canada, but in surgery.

Frank Sinatra sings “I’ll Never Smile Again” with the Tommy Dorsey band (uploaded to YouTube Frank Sinatra / Sony Music Entertainment)

Its poignancy, lyrics speaking to a lost love, would make it equally popular when war came to this country. Indeed, the music of the Big Band era was a cultural glue that held the nation together, a link between the folks back home and the guys overseas.

Some of the hit songs addressed that directly.

“I’ll Be Seeing You in all the old familiar places

That this heart of mine embraces all day through.”“We’ll meet again

Don’t know where

Don’t know when

But I know we’ll meet again some sunny day.”

Others addressed the separation of wartime in a lighter vein:

“Don’t Sit Under the Apple Tree

with anyone else but me

anyone else but me

anyone else but me ….”

Glenn Miller’s “Moonlight Cocktail,” “A String of Pearls, “In the Mood,” and “Chattanooga Choo Choo” were as much a part of my high school days as U.S. history, American lit, Latin and French. His “Elmer’s Tune” was played at my senior class picnic.

Tommy Dorsey’s “Song of India,” “Opus 1,” and “Marie” threaded through those years, too. One afternoon in college, “Boogie Woogie” was played over the P.A. system in the ballroom of one of the dorms. It being wartime, we girls danced together, practicing up our jitterbugging steps.

The hit recording I remember most vividly at college, however, was Glenn Miller’s “That Old Black Magic.” It was played everywhere at the time a measles outbreak landed me in the emergency infirmary ward set up at the school’s country club, a two-story house out by the lake used for social gatherings. A number of us were placed there because there was no room at the regular infirmary.

I was still in the high-fever, chills, where-am-I?-delirium stages when the weekend parties were held downstairs and the music could be clearly heard upstairs. To the point that I still associate my misery with the record, played over and over each evening: “That Old Black Magic … has me in its spell, That old black magic that you weave so well. Those icy fingers up and down my spine ….” The lyrics were appropriate there.

The Big Band music is not only a part of my early years, it’s a golden thread in the tapestry of The Greatest Generation and World War II. A thread spun from Count Basie’s “One O’Clock Jump.” Charlie Barnet’s “Cherokee.” Erskine Hawkins’s “Tuxedo Junction.” Duke Ellington’s “Sophisticated Lady” and “Take the A-Train.” Harry James’s “Music Makers” and “Trumpet Blues.” (James played trumpet in Benny Goodman’s band the night of the Carnegie Hall concert.) Kay Kyser’s “Who Wouldn’t Love You” and “Three Little Fishies.”

The Big Bands and their singers were the beneficiaries of technology, as so many movements and great changes have been. Radio brought national attention. Records spread the musical word to every village and farm, or high school and college. The microphone allowed singers to simply sing, “croon,” it was said, instead of struggling to make themselves heard. (Think opera.)

It didn’t hurt that the time saw an almost unprecedented constellation of great song writers — Jerome Kern, Irving Berlin, Rodgers and Hart, then Rodgers and Hammerstein, Cole Porter on Broadway, and the countless others in movies who gave us songs the nation wound up singing. Harold Arlen and “Over the Rainbow.” Johnny Mercer and “On the Atchison, Topeka, and the Santa Fe,” not to mention two Sinatra classics, “Summer Wind” and “One for My Baby.”

Some of the songwriters are not known today, except possibly to Wikipedia, but gave us the music that the Big Bands and singers made part of our lives. One of Artie Shaw’s biggest hits, “Frenesi,” was written by the little known Alberto Domínguez for the marimba. But one of Shaw’s other great hits was “Begin the Beguine,” by Cole Porter. As was “Stardust,” by Hoagy Carmichael, the ultimate standard. So much so that when I attended a press luncheon for Hoagy Carmichael during my years at the Chicago Daily News and someone asked him what it was like to have written “Stardust,” he said, it was “like having a gilt-edge annuity.”

A galaxy of stars — artists, musicians, song writers, and the technology that “gave it legs” —came together at a time that helped us deal with the stresses and strains of the Great Depression and World War II.

As we lived through those momentous times, we welcomed something we could have in common, could share, could hold onto (and feel good about ourselves or the day or the song). We found it in the courage and courtesy, camaraderie and commitment, which marked The Greatest Generation.

And the music of The Big Bands.

Featured image: Benny Goodman (third from left) with some of his former musicians, seated around piano left to right: Vernon Brown, George Auld, Gene Krupa, Clint Neagley, Ziggy Elman, Israel Crosby and Teddy Wilson (at piano) (Library of Congress)