Saturday Evening Post Time Capsule: July 1932

Featured image: Veteran “Bonus Army” demonstrating in Washington, D.C. (Library of Congress)

Vintage Ads: Putting on the Ritz

By 1934, many families had been forced by the Depression to reduce spending on treats and occasional indulgences. It was the perfect time for Nabisco to introduce the affordable, buttery cracker with a name associated with luxury.

It came from César Ritz, who’d opened glamorous hotels that bore his name around the world. Ritz’s hotels earned such renown as symbols of opulence that ritz became a slang term for something extravagant. Research had shown that up to 90 percent of snack food purchases were made by women, and the men in charge of marketing jumped to the conclusion that female shoppers would be influenced by snob appeal. Hence the name Ritz, which promised a “bite of the good life.”

As a bonus, Ritz crackers boasted a richer taste than most competitors and went for only 19 cents a box. By 1935, a whopping five billion of the crackers had been sold, which worked out to 40 crackers for every man, woman, and child in America. Within three years of its launch, Ritz was the best-selling cracker in the world.

Beyond the Canvas: Flapper-era glamour fades as The Great Depression looms

August 22, 1932.

© SEPS 2014

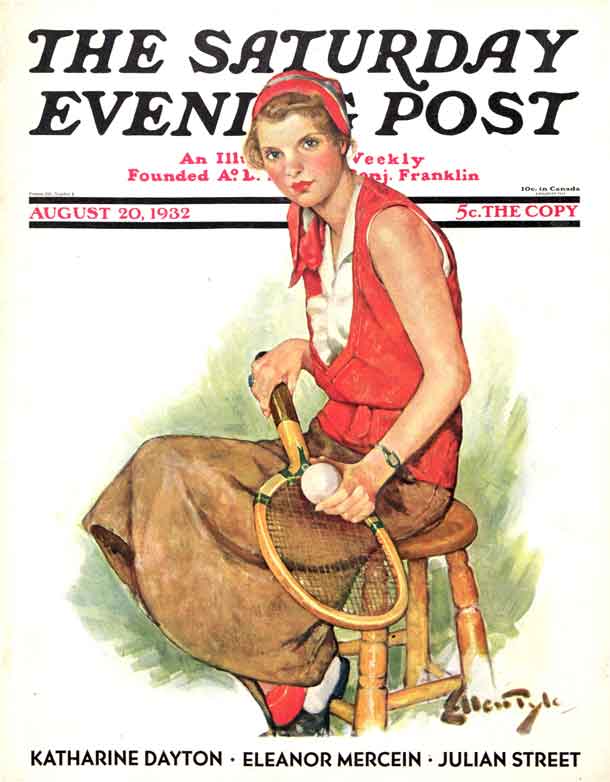

Ellen Bernard Thompson Pyle’s early illustrations for The Saturday Evening Post idealized the 1920s era of glamorous parties and celebration in much the same way Norman Rockwell would later celebrate an idealized rural America of the 1940s and 1950s.

But her notorious depictions of confident flappers in short dresses and even shorter haircuts changed when The Great Depression hit America in October of 1929. Pyle’s color palette and composition took on a darker tone that reflected the nation’s mood.

Pyle’s illustrations from the 1920s and 1930s show women competing in activities like archery, swimming, tennis, gardening, and hockey. The paintings are joyous and playful in the 1920s but become reserved in the 1930s.

Pyle’s August 20, 1932 cover, “The American Girl,” is a perfect example of the change in tone. Where Pyle once showed women smiling in brightly colored outfits, fashionable haircuts, and make-up, this Depression-era cover shows a female tennis player in a muted, brown canvas skirt and a loosely-hanging red top, her hair pulled back by a handkerchief. The glow of her cheeks results from the effort of her workout; it is not the rosy blush of joviality.

Not only has the color and hubris drained from the painting, but Pyle also foregoes her 20s era props of luxurious cars and carriages. This woman just sits on a simple wooden stool. Unlike her carefree flapper predecessor, the American girl of the 1930s is now a resilient heroine who adapts to tougher circumstances. She does without.

The darker color palette of browns and deep reds, combined with the wood of the racket and stool, project an air of simplicity as opposed to the gaudy glam of the decade prior. Rather than show an idealized world of parties that the majority of Americans would never know, Pyle turned to a sense of realism that would better connect with the struggles many Post readers were facing during the Great Depression.