Will Holograms Help Us Grieve?

Long before Kim Kardashian West made headlines for being gifted a hologram of her deceased father for her 40th birthday, a panel session at South by Southwest Interactive, an annual conference for tech innovators, predicted innovations like this as inevitable. As the panel’s program text read: “Grandma passed away last year, but she’s coming back for Thanksgiving dinner this year. This may sound like a horror story,” it continued, “but it could be the future of family reunions.”

The 2015 conversation, titled “HoloGramma: How Tech Can ‘Bring Back’ Our Departed,” discussed how, through extreme technological means, people would one day maintain not only the memory of a deceased loved one—but their very presence in the home.

Whether this concept—that grandma could be switched on, say, in the living room whenever you wanted to see and talk to her—feels creepy, fascinating, or the uncanny mixture of both, consider this: In the modern age is such an idea that shocking? That is, don’t we encounter and interact with the pixelated presence of the dead all the time? For instance, I can make coq au vin at home, guided by an old YouTube video of Julia Child while listening to Prince. Or if my husband and I turn on the morgue that is Turner Classic Movies, we will inevitably pull open the IMDb app to answer questions about the parade of people from the past appearing on the screen. To live a modern media-saturated existence means to swim in ectoplasmic estuaries of life and death, in which living bodies regularly mingle with specters of the long-gone.

Granted, watching Bogie & Bacall is an experience with much less emotional investment than, say, if a “HoloGram” of my late father drifted into the room (though for Bogie & Bacall’s kids, To Have and Have Not may be simply a cruelly titled home movie). Degrees of affect aside, though, many scholars claim that the very experience of any electronic media technology is an essentially spectral encounter. The disembodied voices on radios and the luminous figures on cinema screens constitute what media studies professor Jeffrey Sconce equates with hauntings, writing about a “media occult” surrounding the “seemingly ‘inalienable’ yet equally ‘ineffable’ quality of electronic telecommunications.” Communication scholar John Durham Peters claims that modern media is infused with a “spiritualist tradition”—one we participate in as readily as grieving people in 19th-century America and Europe sought out the services of spiritualists, professionals who claimed to be able to conjure the dead for a brief chat.

It is, as Peters argues, from those very practices of communing with the dead via mediums that we derived our present-day terminology about communication via media. By participating in social interactions designed by and for electronic media, we become more comfortable with these essentially spiritualist encounters. We learn to live with their summonings and ghosts.

Rather than ectoplasm or spirit-stuff, our technical ghosts comprise combinations of words and sounds, fine-tunings of imagery and ideology. Stage celebrities and film stars, TV icons, and pop stars—they are people, of course, but most of us don’t interact with the actual person, with their flesh body. Instead, we participate in encounters with nebulous packages of literal imagery and figurative image, of carefully coordinated public appearances and deftly staged concerts. Philip Auslander, a performance studies scholar, argues it is not the actual celebrity but their performing persona that fans have “the most direct and sustained access” to, not only through their work but also their public messaging.

This persona is carefully and socially managed. A pop star may control much of it, but not all of it. Managers, publicists, handlers of various stripes have a hand in shaping it, as do audiences and fans. So the persona is not the real person nor the fictional character; it’s the liminal figure in between—the one modern media, by its spectral nature, is adept at presenting, projecting, and protecting. And when a public figure dies, their persona continues to be managed posthumously by handlers and fans. Robert Johnson, Woody Guthrie, Mama Cass, Elvis Presley, both dead Beatles, and Tupac Shakur are just a few of the hundreds of artists who sold previously unreleased or even newly crafted records while dead, often selling more recordings from the grave than they did while alive. Orson Welles’s “final” film was just released two years ago. Fans revel in discoveries of “lost” art, interviews, or other ephemera that returns some aspects of a late celebrity’s persona to circulation through the same channels they haunted while alive.

In recent years, though, the celebrity’s posthumous presence has been taken one step further. Numerous deceased pop-music figures—from Roy Orbison to Buddy Holly, Michael Jackson to Whitney Houston—have been resurrected for new performances via animated digital simulations that are projected onto concert stages. These sophisticated animations and apparatuses present likenesses of the performer as if they were present in body as well as spirit. They are staged in a manner that highlights that illusory presence, often with real people on stage interacting with the spectral imagery.

As a former music journalist and current researcher in communication and science studies, I have examined and written about the specific technical means for the production of these “holograms”—an inquiry that began when I received a 2011 press release about “the world’s first virtual pop diva,” a Japanese anime-style character named Hatsune Miku, who has no corporeal existence but who nonetheless headlines concerts in crowded arenas. When I attended a “live” concert by this digitally projected character, in a large theater packed with a thousand rapt fans singing along, the pop-music critic in me wondered whether years of honing criteria for the evaluation of human performance on stages had just been made irrelevant. The scholar in me, however, recognized another intervention of technology into social norms and rushed to connect history and theory to explain the new experience.

The American fountainhead of this trend was Tupac Shakur, who—16 years after his death—headlined the 2012 Coachella music festival. Before an audience of nearly 100,000, the real Snoop Dogg and the real Dr. Dre introduced the “not real” 2Pac, who materialized on stage and performed two songs (one of which had been released after he died, implying a chain of production unbroken by pesky mortality). News media ate up the spectacle, and Twitter went into a twitter.

My own analysis of spectator reactions posted to Twitter within 24 hours of the Tupac spectacle shows that fans initially experienced an expected uncanny unease but then quickly settled into the experience of a reality they were accustomed to through a lifetime of modern media hauntings. What spectators saw were familiar bits of Tupac’s living persona that had been cobbled together and reconstituted for presentation within a musical context that was, in every other aspect, perfectly normal. He looked the same (face, body, trademark tattoos and Timberlands). He sounded right. He boasted and swaggered and performed. The digital Tupac gave little reason for derision (though there was some) or angry cries of fakery (though there were a few) because it provided just enough ingredients from the working persona that fans still recognized from Tupac’s lifetime. No one ran screaming from the festival grounds; they knew or were able to determine that this was a ghost and that it was (somehow) technically produced. They also already knew how to separate the persona from its material media, applying it to a technology almost as easily as they had hung it on his flesh body. By the following morning, fans were speculating (jokingly, but maybe only by half) about a new album by “2.0Pac,” where he might have gone to eat after the show, and who he would soon be dating. They were happily haunted, already living with the dead yet again.

It’s not the first time technology has promised and delivered a mediated afterlife. For centuries, gadgets and gizmos have been invented and sold to feed into on our age-old questions around mortality—about what lives on after we die and how we might maintain contact. From the basic wood-and-glass planchette (later, the Ouija board) to Thomas Edison’s mused-about but never-built “spirit phone” (which was to dial up the departed), these frauds and fantasies, respectively, have offered mystifying possibilities for contacting or manifesting the presence of the dead. The performing hologram is the latest materialization of mediated spirituality—a new iconic image, like those of saints, as philosopher Matthew Harris has written, wielding power “much in the same way that a relic has power for the religious devotee.”

These performing hologram systems are simply HoloGramma writ larger. They are technical projections of an embodied simulation of the dead back into a real space for new social interactions among the living. They are media doing what media do—presenting a person’s persona within specific contextual frames, regardless of where that person’s body might be, or if it might be.

The idea of holographic grandmothers is simply a dimensional extension of existing media interactions between the living and the dead. While a Tupac or Kardashian hologram is currently beyond the means of most, the average person’s persona imprinted across digital platforms is not buried as efficiently as our body, nor does it decay as swiftly. This data may not only live on through the networks, it may also continue to act. Which suggests the future of posthumous presence begins in the ways we currently organize and nurture, while we live, the mediated elements of persona that will survive us—and that may be crucial to the grief and mourning of loved ones left behind.

This is already happening. Each March, for instance, Facebook friends and I still wish a former colleague a happy birthday, even though he’s been deceased for several years. He responds, too—or his sister does, anyway; she manages Brian’s online afterlife, posting alongside his eternal photographic smile.

It’s no fireside chat with HoloGramma, mind you, but every knitted scarf begins with a few innocent strands.

Originally appeared on Zócalo Public Square. Primary editor: Jackie Mansky; Secondary editor: Eryn Brown

Featured image: Peshkova / Shutterstock

Learning to Grieve

We are left with the impulse. You reach for a glass that isn’t there, and your hand swishes through empty air. You step down and the stair is missing and you stumble into space. Grief is the frozen moment when you pat your pocket for your keys, the pocket where you always put your keys, and your keys aren’t there. The intensely familiar is gone — not just a person, but a habit. Gone. When I do this, that happens. When I say this, you answer. When I reach for you, there you are. And then I am reaching, and nothing, nothing is there. The true has become false.

Grief is disruption. The sound of a footstep on the porch evokes the old world, the other life, and it is only the mail carrier and the new life rushes back. My mother has been gone from my life for more than 30 years, but I hear her voice sometimes when I talk, and I see her in the mirror now and then — sidelong, unexpected glances. There she is. And I think, I should call Mom and tell her about that. Grief recurs and spins, a Möbius strip of memory going on and on in a loop. You aren’t in denial about the death. You just keep remembering that it happened.

You flinch. You know it will hurt and you know it will hurt for a long time. You touch it like an abscessed tooth and skid away. Grief lives in the body. MRI studies show that a grieving brain has a pattern unlike other emotions. Most of the time, an emotion lights up parts of the brain, but grief is distributed everywhere, into areas associated with memory, metabolism, visual imagery, and more. Grief can make you sick; it can be brutal, even deadly. One is coming to grips with what forever means. And we don’t do that all at once and we don’t do it one day at a time but for one minute and then another minute and then another. Don’t ever say: Get over it, move on. She’s in a better place now.

You know it will hurt and you know it will hurt for a long time. You touch it like an abscessed tooth and skid away.

Grief is full of surprises. Anything is possible. You may feel unreal, drugged. Numbness is one of the most common sensations. You may be calm or excited or enraged. You may be so relieved, relieved that it’s over, the illness, the injury, the weeks and months that turned into a waiting room in which no one’s number was ever called. Then you are overwhelmed with guilt for feeling relieved. It’s all very confusing: hard, difficult work. Work! No one tells you that grief is like a long march in bad weather. You’re forgetful and find it hard to make decisions and have no interest in the decisions you are being asked to make. You lose track of time, because time changes, too, shifting and slowing, speeding up, stopping altogether. An hour becomes an elastic, outrageously delicate thing, disappearing or stretching beyond comprehension. One is deranged, in the truest sense of the word: everything arranged has come apart.

In grief, I have baked a cake in the middle of the afternoon and left out the sugar and not been able to figure out why it tasted so bad. I have watched a lot of television and stayed up very late and had many strange dreams that evaporated in the morning light. I have awoken each morning to the shock renewed, to think, He died. She died. Decades of Buddhist practice and many hours at the bedsides of the dying, and all that these have given me in my weeks of acute grief is not acceptance but awareness of not accepting. I can see my disbelief for what it is. I think, He died, and then take a deep breath and reset my compass to this new world. This new world in which a person who had immense influence on my life does not exist. This vacuum. I am dead, too; the me that lived in the other world, the world where she was, died. The me who knew instinctively where he was and suffered a little when he was far away died. Who am I now? All the possibilities of the life of that former me, the me-with-her, are extinguished. Grieving, one is thrust into a new life — an unwelcome life. It takes time for that life to become familiar, to feel like the life you are actually living. You can be happy again, but you can never be happy and the same again.

A friend of mine called the numbness that falls over you immediately after a death “like swimming in thick gelatin mixed with cotton candy and filled with webs and you’re trying to push it aside and you can’t push it aside.” You may not remember much of the days after a death. I remember little about my mother’s funeral, though I did a lot of the organizing. I remember the fight my brother and sister had afterward, the casseroles on the dining table. But I don’t remember how we got the church ready or if there were flowers or what my father did that day or what I wore. I remember sitting in the backyard late that night, drinking bourbon with her friend Hutch, the music teacher who had been my bandleader in middle school. We were drinking and watching the stars, and I was so tired. Nothing will be the same, I thought, leaning back in the chaise longue as though into a pool, sinking into the warm dark night. I remember that.

You have trouble remembering details while the rest of the world forgets the big event. People are almost surprised that you haven’t forgotten, too. What we miss is often the most mundane thing. How she folded a towel. The sound of his foot on the porch. Her handwriting. I keep a recipe card from my mother’s collection on my bulletin board because she had beautiful handwriting and she tried to instill that in me, with little luck. You miss the snore that used to annoy you so. The scent of soap. The pat on the bottom. Small, ordinary things that no one else misses. You can’t say to a grieving person who is suddenly frantic about not being able to do the laundry together that doing the laundry isn’t important. Only the grieving person knows why it is so important, why not being able to do the laundry together is an immeasurable loss. The loss may be accepted in time, but this isn’t the same as “getting over it.” There are so many things not to say now: At least your mother and father are together again. He’s in a better place. You’ll marry again someday.

Crying is neither necessary nor sufficient. The grief-counseling partners John W. James and Russell Friedman write, “During our grief recovery seminars, when someone starts crying, we gently urge them to ‘talk while you cry.’ The emotions are contained in the words the griever speaks, not in the tears that they cry. What is fascinating to observe is that as the thoughts and feelings are spoken, the tears usually disappear, and the depth of feeling communicated seems much more powerful than mere tears. … Tears [can] become a distraction from the real pain.”

Regret is inevitable. Not one of us has lived a life without error. Grief is remorseful. Grief is angry. Angry at the disease, at the terrible choices that had to be made, at the stolen days. Angry at the accident, the mistake, the stupidity of death. Angry at the dead person. How dare you go away? How dare you leave me alone? Angry at everyone involved, everyone who didn’t stop death. We long to blame someone. Why wasn’t she wearing a seat belt? Why didn’t he tell anyone he had chest pain? Why wouldn’t he quit smoking? Anger can be a way for the survivor to deal with the fear of surviving: How do I go on? How do I live now?

Religion doesn’t fix grief. (Don’t say: God always has a plan.) Explanations don’t fix it, advice doesn’t fix it, sharing doesn’t fix it. All these things may help immensely, but grief is not a disease to be cured. Grief is a wound not unlike that from a knife or a bludgeon. The injury will heal in time, leaving a scar, but the tissue is never quite the same. One moves forward, changed.

Grief is the internal experience of loss. Mourning is its outward expression. Together we call this bereavement, a wonderful word. Its root comes from the Old English berafian, which means to rob.

Try not to say: You shouldn’t dwell on the past. Grief is a story that must be told, over and over. Very few people know how to listen to a grieving person without in some way trying to shut down or control the strong emotion. Because it is hard for others to listen, the grieving tell each other the story of their losses, over and over. There are so many things not to say. What are the things to say? I love you. I’m so sorry. And one of the best things to say is Do you want to talk? I would be glad to listen to the story. The story of how you met, of what he was like as a child, of her favorite food, of that trip you took together to Iceland, why he liked that blue plaid shirt so much, what the last moments were like. Whatever story you want to tell.

Sometimes grief isn’t recognized; others don’t understand why you grieve, or grieve with such passion. The loss seems relatively small: a divorced partner, a spouse with end-stage dementia, an early miscarriage. There are no bereavement fares for a best friend or business partner. People may not even realize you are grieving: a secret affair may never be divulged, but the loss is real. This is sometimes called disenfranchised grief. Grief unrecognized or undervalued is real and disabling.

After unexpected or violent deaths, the survivors may feel what is commonly known as complicated grief: pain that remains sharp and unchanging for many months or years. I’m a little wary of this label, because grief has no strict timeline, no prescribed schedule in which one moves forward. But most people do move forward over several months or a few years, even if they think of the dead person every day. A new life without the person in it is slowly created.

The grief counselors James and Friedman developed a program they call Grief Recovery Method, based on James’s experiences after his three-day-old baby died. Their work is based on the idea that unresolved grief happens because “the griever is often left with things they wish had happened differently, better, or more, and with unrealized hopes, dreams, and expectations for the future.” This can be true in healthy relationships as well as dysfunctional ones, anticipated deaths as well as sudden ones. The relationship feels suspended, unfinished, with no way forward. Recovery means, to James and Friedman, letting go of “a different or better yesterday.”

James and Friedman recommend writing a detailed history of the relationship: highs, lows, successes, failures, resentments, joys. Finally, James and Friedman suggest writing the dead person a letter (never to be shown to anyone): a “completion letter rather than a farewell letter.” The relationship as it was is over. Completed. The relationship, however complicated, was whole, had a beginning, middle, and end, had good times and bad.

Very few people know how to listen to a grieving person without in some way trying to shut down or control the strong emotion.

After my mother died, I went through a gradual recovery. All James and Friedman are telling us is to consciously do what people have always done with death. Experience it. I talked to her, I looked at photos, I read letters, I talked to myself, I talked to (and I am sure that I bored) my friends. I told a lot of stories, silently and out loud, about my mother at different times of our life together, her past before I knew her, how she handled her illness, her career as a teacher.

Our relationship improved. We didn’t argue anymore — which is to say, I didn’t argue with her anymore. She listened to me and I told her secrets. As time went on — years, decades — my ideas about her and myself, about mothers and daughters, changed. My memories grew a bit rosy; I had fantasies about what my life would have been like if she’d lived longer. She’d have known her grandchildren, enjoyed her retirement. In my mind she outlives my father and we go to Reno and she gambles all day and we drink martinis by the pool in the summer evening. Happy fantasies. But I know they are fantasies; they are no longer regrets.

Kobayashi Issa was a famous Buddhist haiku poet in Japan’s Edo period. After two of his children died in a short time — two of many losses he would suffer — Issa wrote this poem:

The world of dew is a world of dew, and yet, and yet.

Dew, fleeting and fragile, is the nature of life. While we understand, somehow, that this is precisely what love is — that the china bowl is beautiful precisely because it will break, that we love each other because we do not live forever — we can barely imagine what that means.

A common phrase on 19th-century tombstones went: “It is a fearful thing to love what death can touch.” A part of us holds back from love, always protecting itself, selfish, uncertain. After a death, there is no longer anything to fear. At last. At last, we lose that which we want most to keep. Then there is nothing more to lose. Then the human fears that drive us apart — our concern for the opinion of others, our pride, our shame — are revealed to be so very small. We see what really matters. And when we contemplate the one we have lost, our hearts are free of hesitation, holding nothing back. Grief is the opportunity to cherish another without reservation. Grief is the breath after the last one.

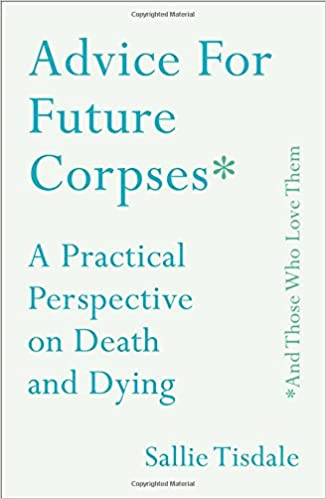

From Advice For Future Corpses (And Those Who Love Them): A Practical Perspective On Death And Dying By Sallie Tisdale. Copyright © 2018 By Sallie Tisdale. Reprinted By Permission Of Touchstone, A Division Of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Sallie Tisdale is also the author of Talk Dirty to Me, Stepping Westward, and Women of the Way. Her work has appeared in Harper’s, The New Yorker, and Antioch Review, among others.

From Advice For Future Corpses (And Those Who Love Them): A Practical Perspective On Death And Dying By Sallie Tisdale. Copyright © 2018 By Sallie Tisdale. Reprinted By Permission Of Touchstone, A Division Of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Sallie Tisdale is also the author of Talk Dirty to Me, Stepping Westward, and Women of the Way. Her work has appeared in Harper’s, The New Yorker, and Antioch Review, among others.

This article is featured in the September/October 2020 issue of The Saturday Evening Post. Subscribe to the magazine for more art, inspiring stories, fiction, humor, and features from our archives.

Featured image: Shutterstock