The Larger-Than-Life Artist Behind Mount Rushmore

It began as an ambitious plan to boost tourism in South Dakota in 1926. When it was completed 15 years later, it became an American landmark and a symbol of the nation’s determination and skill. In between 400 workers did the grueling work of blasting and drilling 410,000 tons of granite from the side of the mountain under the supervision of a gifted sculptor named Gutzon Borglum.

But Borglum’s gifts weren’t limited to pulling heroic images out of mountains. He also showed considerable talent in promotion, both for the project and for himself. As the governor of South Dakota during Mount Rushmore’s construction, William J. Bulow was well acquainted with this side of the artist. His article “My Days with Gutzon Borglum,” which appeared in the December 1, 1947 issue of the Post, outlines Borglum’s fickle and often maddening ongoing requests and demands, as well as his genius.

Securing the necessary funds for the project proved as difficult as carving the gigantic granite heads. The federal government approved the project in 1926, but most of the work was performed during the Great Depression, when money was particularly hard to come by. Ultimately, the memorial was a scaled-back version of Borglum’s original design. He had intended to sculpt the presidents down to their waists, but time and money were too limited.

Time was even more limited for Borglum himself. He died in March of 1941, leaving his son, Lincoln Borglum, to complete the project. Later that year, funding ran out: The government was focused on rebuilding national defense (the Pearl Harbor attack was just weeks away.) So Mount Rushmore was declared completed on October 31, 1941.

Though it wasn’t as grand as had been originally intended, Borglum left an enduring tribute to four presidents who represented the founding of the nation (Washington), its expansion (Louisiana Purchaser Jefferson), its development as a global power (Roosevelt), and the preservation of the union in the Civil War (Lincoln). Today, this national memorial is maintained by the U.S. National Park Service.

But Mount Rushmore is also a tribute to the artist, who emerges as a larger-than-life figure in Bulow’s article.

My Days with Gutzon Borglum

By William J. Bulow

Originally published on January 11, 1947

Ever hear about the time when the famous sculptor walked up Mount Rushmore in the rain and got his white pants dirty? The governor of South Dakota heard plenty about it — and other unfortunate incidents.

In the spring of the first year I was governor of South Dakota, the annual convention of the Young Citizens League was held at Pierre. This was a new state-wide organization of school children below the high-school grades, and I was much interested in its welfare and success. At one of the convention sessions, Doane Robinson, the state historian, submitted a proposition that the Young Citizens League take charge of raising funds for the Rushmore Memorial. Until that moment, I had never heard of the Rushmore Memorial.

I listened to the proposal and then asked for permission to appear before the league in opposition, contending that the children in the grade schools ought not to be burdened with a proposition of this kind. The league turned the proposal down.

Not so long after that, however, Doane Robinson, in company with Gutzon Borglum, came to me and with a good deal of enthusiasm discussed what they had in mind. It sounded all right, but at that time I was not much excited. Their plan was to raise the necessary funds by public donation and subscription. Funds for a starter had already been subscribed.

Borglum, who was a born promoter, then worked up a great advertising stunt by having President Coolidge, while he was visiting the state, dedicate the mountain. The services drew a tremendous crowd of people. In addition to the President’s address, the event gave Borglum a chance to make a speech and tell what he intended to do. He actually had the fortitude to “authorize” President Coolidge to prepare a short history of the United States, of a few hundred words, which he, Borglum, would then carve on the mountain peak opposite the gigantic statues of Washington, Jefferson, Lincoln, and Theodore Roosevelt, which he planned to hew out of the granite. President Coolidge accepted the job, but he didn’t know what he was getting into. When the manuscript was completed and submitted several years later, about the time Mr. Coolidge’s term expired, the sculptor decided it was wholly unsatisfactory and turned it down flat.

Next, Borglum got the Hearst newspapers interested in a Mt. Rushmore promotion scheme and staged a widely publicized contest, offering a first prize of $10,000 for the best short history of the United States. More than 10,000 persons, from all sections of the country, submitted manuscripts. A general committee was named to select the five best, and the five thus chosen were submitted to a special committee of five United States senators for the final choice. By that time I was a member of the United States Senate and was one of the committee of five.

In my judgment, all five manuscripts were excellent; any one of them was worth carving on the mountainside. The committee made its choice, and Borglum promptly turned it down. Moreover, he took a look at the four others and threw them away. He said that someone would have to produce a better history than had yet been written or he would write one himself. Borglum had, however, accomplished one of the things next to his heart — the advertisement of Gutzon Borglum and Mt. Rushmore. A million dollars could not have purchased the advertising that the Hearst papers gave Gutzon, Mt. Rushmore, and the state of South Dakota in publicizing the contest.

The original Mt. Rushmore committee was a group of local citizens that Doane Robinson had gathered together and interested in the proposal. This committee was succeeded by a larger and very prominent group of wealthy and philanthropic citizens scattered all over the United States. Considerable sums of money were thus raised in the earlier stages of the work. In order to give more permanency to the project, Congress created the national Mt. Rushmore Commission, the members of that commission to be appointed by the President. Since the death of the sculptor several years ago, the Rushmore Memorial has been placed under the supervision of our national-park system. From the time Congress created the Mt. Rushmore Commission, the work has been financed by federal appropriations from year to year.

One of my headaches during my 12 years in the Senate was the obtaining of necessary appropriations to keep the work going. Gutzon Borglum was not an easy man to work with, but he was, I am convinced, a really great sculptor. I doubt that any other artist living had the vision and the ability to carve those magnificent heads in the living granite of a mountainside. But as a financier and diplomat, Gutzon stood down on the bottom round of the ladder. To obtain the necessary appropriations for the first few years under the national commission was comparatively easy, but the job became harder each year, until toward the last it was nearly impossible.

Borglum always insisted that he himself should appear before the appropriations committee in behalf of his requested budget. His memory was not very good and he had difficulty in remembering his statements from one meeting to another. Some of the committee members, on the other hand, were hard-boiled and had good memories. Gutzon would nearly always end his plea to the committee with the promise that this would be the last appropriation he would ever ask; this would wind up the job. The next year he would be back asking for a substantial increase because he had thought of a lot of new things that he was going to add to the memorial.

At one point he decided that there ought to be a Hall of Fame. This was to be housed in a large cave excavated in the solid granite of the mountain and would include an archives room where the national records could be stored and sealed — to be opened in 10,000 years. In due course of time he had talked a number of prominent people into letting him make marble busts of them, to be placed in the archives room. And then he thought he ought to carve a stairway from the bottom of the mountain up to the doorway of the Hall of Fame and to the room of archives.

I remember particularly the bitter dispute between Mr. Borglum and Senator Norbeck about the stairway. This was in the New Deal leaf-raking days, the days when the government was hiring people to carry stones from one pile to another and then back again. Senator Norbeck had arranged for a government works project to build this stairway with idle labor in that vicinity. It would be paid for from relief funds and not from Mt. Rushmore funds.

Gutzon blew up when he heard this proposal, and he and the senator got into quite a row. Borglum was no financier, but he knew that he was getting a very liberal percentage commission for every dollar that he spent on the memorial; if the stairway was built with relief labor, he would get no commission on that part of the project. This would be bad, and he would not stand for it. The plan to build the stairway with relief funds was dropped. In fact, the stairway has never been built.

Work was started on the Hall of Fame and the archives room, but never finished. Over the years I urged Borglum in every way that I could to devote all his time to completing the carving of the figures. That was work that he, and only he, could do. If he should die before their completion, the job would never be finished. Any miner, I told him, could blast out the cave in the mountain for the archives room, but there was no one else who could carve the face of Lincoln on the mountain.

Borglum did not expect to die when he did and leave the job uncompleted. The last talk I had with him was just a few weeks before his death. I was begging him to complete the figures, as I had begged him many times before. He said that I need not be disturbed about that. He had just gone through a clinic and had had a complete physical checkup; he was in perfect health, he said, and would live for many years.

I know from personal experience that no one could get along with Mr. Borglum for any length of time without losing his temper — unless one was a saint, and there are few human saints. I never had so many rows with any other person as I had with him — sometimes over important things, but more often over little, insignificant things. We were probably equally to blame. Borglum never carried a grudge.

Early in our acquaintanceship, we often parted in the evening with Borglum vowing he never would speak to me again. But the next morning would be a brand-new day, and Borglum would extend a hearty handshake and a cordial good morning. That cordiality would hold good if we did not visit too long. If we talked too much and discussed too many subjects, it would become necessary for us to part again in anger. Most of my first year as governor, Gutzon constantly made life miserable for me. His chief peeve at that time was that there was no road to Mt. Rushmore. There was just a trail that could be traveled only on foot or by horseback.

When President Coolidge dedicated the mountain he rode horseback up the mountain trail and wore a ten-gallon cowboy hat. There were a few other horseback riders, including Senator Fess, of Ohio. Senator Fess was not a good bronco rider and he was lagging a little behind. The President said, “Senator, ride up here by my side — it won’t hurt you any.” There were not broncos enough to go around, so I walked, as did several thousand other people who climbed the mountain trail that day.

To Borglum, Mt. Rushmore was the most important thing on Earth — the center of the universe. Everything else was of secondary importance. But Mt. Rushmore had no highway leading to it. It must have a highway. The State Highway Commission must build this road at once. The governor was chairman of the highway commission, so Mr. Borglum took all matters up with me. Almost every day he would demand that the road be built, and after each demand he expected that the job be completed before breakfast next morning.

I especially recall one telegram that he sent me. I recall it because it was the longest telegram I ever received and contained the most expressive language. There were more than 300 words in that telegram, and Gutzon didn’t repeat himself. Every word meant something. It was a masterpiece. I wish now that I had kept it to insert here. I remember, among other things, he said that he had just returned from the mountain. That it had rained. That he had worn white shoes and a new pair of white dress pants. That he had driven his car as far as he could and then walked. That he had ruined his shoes and new white pants. I wired him suggesting that the next time he went to the mountain in the rain he ought to put on a pair of overalls and go barefooted. This advice held him down for several days, but in a short time he was lambasting again.

We got the road built as soon as we could. First a good graveled highway and later a hard-surfaced road. After that first dedication, people could travel to the mountain by automobile. Borglum had a habit of dedicating the mountain about once every year. I attended a number of these dedications. The last one I attended was when he had President Franklin D. Roosevelt come out and dedicate it. There was a tremendous crowd attending on that occasion. I thought then that now at last the mountain was properly dedicated, and that it would not be necessary for me to attend any further ceremonies of this sort. I never did. But I have visited Mt. Rushmore upon many occasions since then and always enjoyed the visit.

On one occasion when Mr. Borglum was in Washington urging the necessary appropriation to continue the work, he arranged with President Roosevelt for a meeting in the executive office, to which he invited all senators representing states carved from the Northwest Territory. Most of the senators attended. Borglum was the orator to make the speech to the president. He was a good orator. He was then stressing the importance of carving a short history of the United States on the mountainside. He said he intended to carve this history in four languages, English, Latin, Greek, and Sanskrit.

Senator Tom Connally, of Texas, thought it was time for a question. He blurted out, “What in the world do you want to cut it in Sanskrit for? Nobody reads that.”

Borglum turned on Tom with a withering look of scorn. Striking a dramatic pose, he said, as nearly as I can now recall: “Sir, Mount Rushmore is eternal. It will stand there until the end of time. This age will pass away and all its records will be destroyed; 10,000 years from now all our civilization will have passed without leaving a trace. A new race of people will come to inhabit the earth. They will come to Mount Rushmore and read there the record that we have made. If that record is written on that immortal mountain in four languages, those people will not have the difficulty in reading our record that we had in figuring out the hieroglyphics of Egypt.”

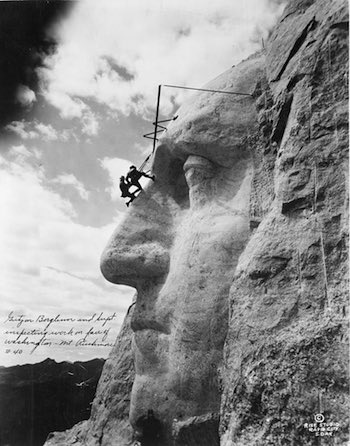

Gutzon Borglum never lived to carve that history on the mountainside, but he had the vision. No other man has ever had the perspective to carve such gigantic figures and make them look natural to the human eye from any spot below. Several times I climbed into the basket and rode up the cable to the mountaintop and inspected the carvings at close-up view. The close-up view is disappointing. You cannot see the face of Lincoln when you stand on his lower eyelid; you cannot see Washington while walking back and forth on his lower lip. It takes a genius to figure out the proper perspective so that the carvings will look right from the point from which the human eye beholds them. Gutzon Borglum was that genius.

On one occasion I was visiting him at his studio at the foot of the mountain. We were out on the porch looking up at the mountaintop, where a number of men were working on the carvings. He said Washington wasn’t right. His head did not sit right. He was going to turn the head around a little. I asked him how in Sam Hill he was going to turn Washington’s head around in the solid granite of the mountain. He took me into his studio and showed me his model, pointing out how he would chisel off a little here and a little there. I could not see his point at all. But a few months after that, I was up there again, and Gutzon Borglum had turned the head of Washington around.

Those of you who have visited our National Capitol and looked at the bust of Abraham Lincoln have seen a marvelous reproduction. Gutzon Borglum’s Lincoln is, I think, by far the best. Many times have I stood and gazed upon that marble bust and marveled at its beauty. No other artist in all the world could take a piece of cold and expressionless marble and reflect there so well the likeness of the face of America’s best beloved — the most beautiful face in all American history.

Upon one occasion Mr. Borglum and I were visiting in the Rotunda together. We stood before the bust of Lincoln. I complimented the sculptor, as best I could, on his work, and he told me that the Lincoln bust was the work of a lifetime. Before undertaking the task he had spent years in studying the life of Lincoln; he had read every book that had been written about Lincoln; he knew Lincoln and had his likeness emblazoned upon his own memory before he undertook to produce the likeness in marble. Those of you who have made a pilgrimage to Gettysburg have seen the memorial there erected by the citizens of North Carolina in honor of their heroic dead. That monument is a group of soldiers cast in bronze — and it was created by Gutzon Borglum. Everyone who has ever looked at that monument returns for a second look, and then for a third. It is by all odds the most attractive memorial on that historic field.

The best view of Mt. Rushmore, I feel, is the one seen as you look through the tunnel, as you drive up the paved highway toward the mountain. As you approach the entrance of the tunnel, looking through it, you see the four heroic figures as if they were encased in a picture frame. As one looks at Mt. Rushmore from any angle, it is awe-inspiring. I have never talked with anyone who has not admitted that his heart beat faster with patriotic pride as he gazed upon that heroic shrine.

People who claim to know tell me that Mt. Rushmore is not subject to erosion; that its granite is everlasting; that a thousand years of winter snows and winter storms, and a thousand years of summer rains and summer suns will leave no mark upon it. Generations hence, when we who had our troubles with Mr. Borglum are forgotten, the name of the man who carved those noble figures in the granite will be remembered. Gutzon could be a little difficult at times, but there was greatness in him.

Featured image: Borglum with his model of Mr. Rushmore (Library of Congress)