The Art of the Post: The Most Stubborn Illustrator

Read all of art critic David Apatoff’s columns here.

Of all the great artists whose works appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, none traveled farther to get there than Harvey Dunn.

Dunn was born in 1884 on the prairie of South Dakota, along an ancient buffalo trail. His parents were homesteaders living in a seven by nine foot wooden shanty. Life was rugged and work was hard, but as the young family gradually tamed the land, their situation improved. When Dunn was four, his father was able to uproot their shanty and drag it by oxen to a better location. The family then acquired a few horses and added more land to their farm. Dunn grew up performing farm chores from sunrise to sunset, including plowing the hard soil and hoisting 150-pound sacks of wheat from the family’s thresher.

When he could, Dunn attended a one-room schoolhouse to learn basic reading, writing, and arithmetic. He was not a good student, but he loved to draw pictures on the side of the schoolhouse.

Dunn soon grew into a 6’2”, broad-shouldered young man with powerful features and a stubborn backbone. He would need every ounce of that strength and determination to plow his way from the prairie to the offices of The Saturday Evening Post in Philadelphia.

Dunn loved to draw and set his heart on becoming an artist. His father thought this was foolishness and tried to persuade Dunn to continue on the farm by offering him 640 acres of prime farmland for his very own. However, Dunn was determined to learn to draw and dreamed of going to the nearest school, the South Dakota Agricultural College in Brookings, South Dakota, 50 miles from the farm.

In order to pay for school, Dunn made extra money by plowing land for their neighbors. He was paid $1.25 an acre. He would start before daybreak and plow until 10 a.m. when the horses would become too exhausted to continue. He would then swap the initial team of five horses for a fresh team and go on plowing until 4 in the afternoon, when he once again swapped horses and continued plowing until well after sunset.

In 1901, at the age of 17, Dunn had earned enough money to enroll at the Agricultural College. An art teacher there soon recognized Dunn’s talent and urged him to continue his studies at a school that was better equipped to give him the training he needed — the Art Institute of Chicago. His family reluctantly agreed and Dunn went to Chicago to begin serious study in art. But the Art Institute turned out to be a more formal and rigid place then Dunn expected; they started him off in a junior composition class performing basic exercises such as organizing geometric shapes into compositions. Dunn thought this was a waste of time, so he went over the heads of his teachers to a senior class professor and showed his drawings of South Dakota. The professor agreed with Dunn so the young man was able to bypass some of the basic classes.

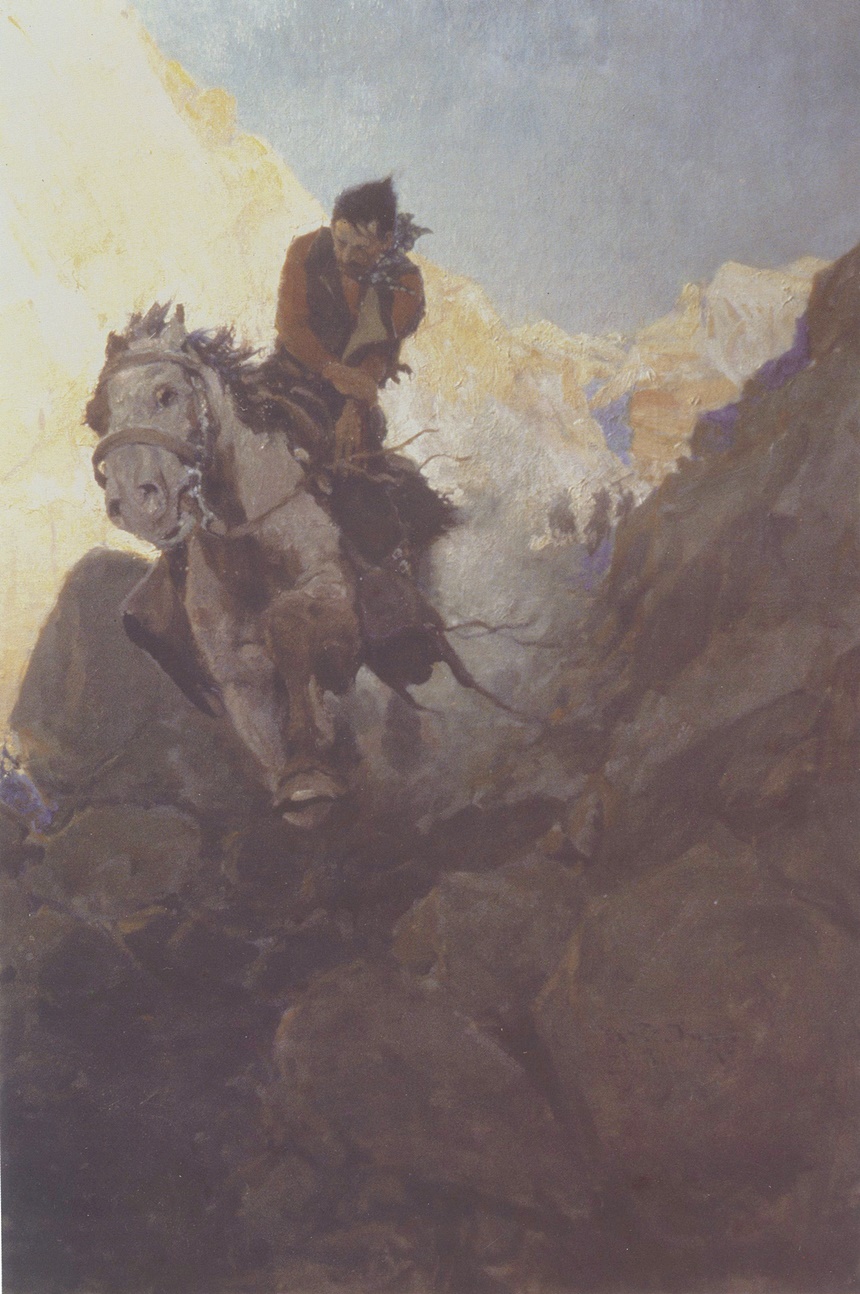

By 1904, Dunn was ready to skip ahead once again. He left the Art Institute for The Howard Pyle School of Illustration Art, the foremost school for illustrators in the country. Dunn went to study “under the grand old man Howard Pyle, whose main purpose was to quicken our souls that we might render services to the majesty of simple things.” With Pyle’s encouragement, Dunn began looking for work as an illustrator.

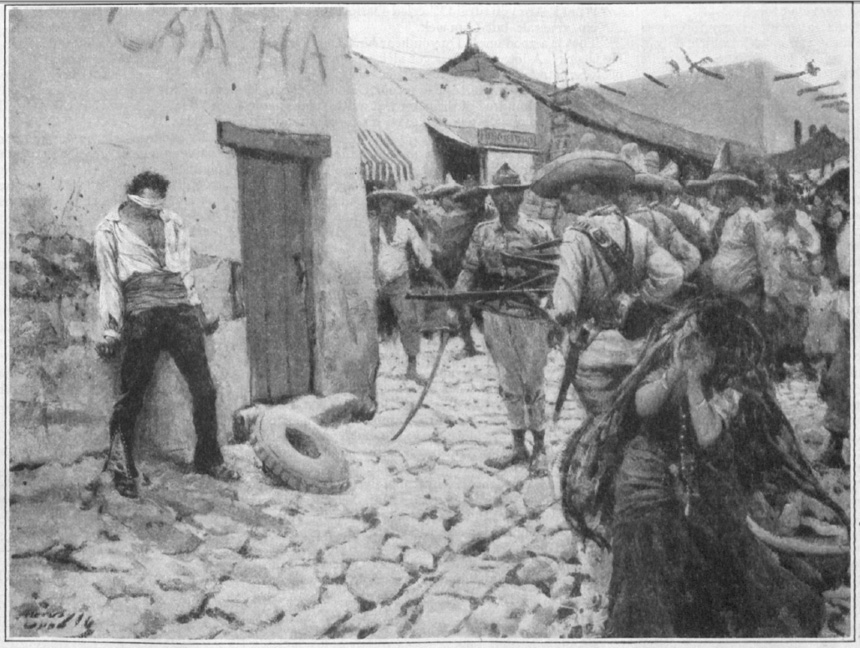

His very first art job came from The Saturday Evening Post in 1906. After being turned down by many other magazines, Dunn described his encounter with the Post: “[O]ne day I went to see Mr. Hardy at the Saturday Evening Post in Philadelphia. He looked my work over. Seemed delighted.” Dunn was skeptical. He had heard plenty of compliments from previous art directors, but they never resulted in a job, so he assumed Hardy was just brushing him off. However, “a week or so later, I was surprised to get a package from the Post and it is a manuscript with the note of the fact that they wanted five illustrations for it… I was in my seventh heaven.”

Dunn quickly painted all five illustrations in just five days. Then he discovered that he was supposed to submit preliminary sketches to the Post for approval before painting final versions. Dunn set the finished five paintings up against the wall and sketched them for approval by the Post. He described his next meeting with Hardy: “I went to Philadelphia with sketches and pictures in separate packages. I left the five paintings in the corridor outside while I went in to see Mr. Hardy with my sketches. He looked them over, seemed to like them. ‘Fine,’ he said. ‘Now when can I have them?’ ‘Just a minute, Mr. Hardy,’ and I went out into the corridor and brought in the five finished paintings.”

This was the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship for both the Post and Dunn. As one of Dunn’s biographers, Walt Reed wrote:

Dunn’s first patron and the longest lasting of his magazine affiliations was with the Saturday Evening Post. Its editor in chief was George Horace Lorimer, a man of strong convictions and a belief in the virtue of hard work as the route to success…. Lorimer saw that same spirit exemplified in the artwork of the young illustrator. Dunn’s ability to depict the cow hands, farmers, miners and factory workers who were the backbone of the country appealed to Lorimer, and he instructed the post art editor to keep the young Dunn supplied with manuscripts to illustrate. This association with the magazine continued over a period of 35 years.

Dunn went on to become one of the top illustrators in America. His work is displayed in fine art museums today, and is featured in several books. He also devoted a substantial portion of his career to teaching other young artists, and became famous as a mentor to a whole generation of talented illustrators.

Quite a distance to go for a young farmer from South Dakota.